PHOTOGRAPHER OF MODERN LIFE CAMILLE SILVY

ARCHIVE

MARK HAWORTH-BOOTH

Back in the early 1970s, when many people began to recognize that photography had a secret life as a creative medium, I used to ask fellow enthusiasts if they could recall the moment when they "got it." Usually they could, down to the very book, magazine photo-essay, or exhibition. I always had my own answer ready: Bill Brandt’s retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, London, in 1970 (I thought of myself as a modernist, and Brandt extended my pantheon of modern heroes).

However, something unexpected happened two years after that show. I was working as an exhibition curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum and watched as a new show was being installed. From Today Painting Is Dead: The Beginnings of Photography included a photograph that made me stop and stare, and then buy dozens of postcards in the exhibition shop: River Scene, France (1858) by Camille Silvy (1834-1910). It probably appealed to me,

I thought, because I grew up by the water-reflections in a Sussex millpond. Whatever the reason, it was a Barthesian “punctum,” top to bottom and edge to edge, and pierced me to the quick.

Five years later I was appointed the V&A’s curator of photographs and became responsible for Silvy’s picture (plus three hundred thousand others). I began to find out about the photograph that fascinated me so much—that the river was called the Huisne, the location was the market town of Nogent-le-Rotrou, about an hour’s drive west of Chartres—not far from Marcel Proust’s fictional river, the Vivonne, at Illiers-Combray. I learned that the then rather obscure Silvy had made the photograph at the age of twenty-four and that it in turn had made him famous. The image I saw in 1972 was a deep, dark, gold-toned albumen print, sharp as a daguerreotype. It had been bequeathed to the museum by the collector Chauncy Hare Townshend (the man to whom Charles Dickens dedicated Great Expectations). Silvy exhibited the photograph to acclaim in Edinburgh, London, and Paris. The sustained critical applause for the image stretched to 1939, when it was shown at the V&A to celebrate the first hundred years of photography, and then illustrated in the first paperback history of photography, by Lucia Moholy.

It took me several years to realize that Silvy’s river scene was as highly constructed—and in fact modern—as anything by Bill Brandt. Silvy selected and arranged a cast of characters in this pre-impressionist tableau—the country bourgeoisie on private property at the left, the “common people” on common land at the right. Both groups of people were doing something particularly modern by “performing leisure” (to borrow a phrase from the sociologist Thorstein Veblen). Silvy’s artifice extended to inserting a sky from another negative, balancing it with an emphatic foreground burn-in, and freely adding foliage by retouching his large, collodion-coated plate.

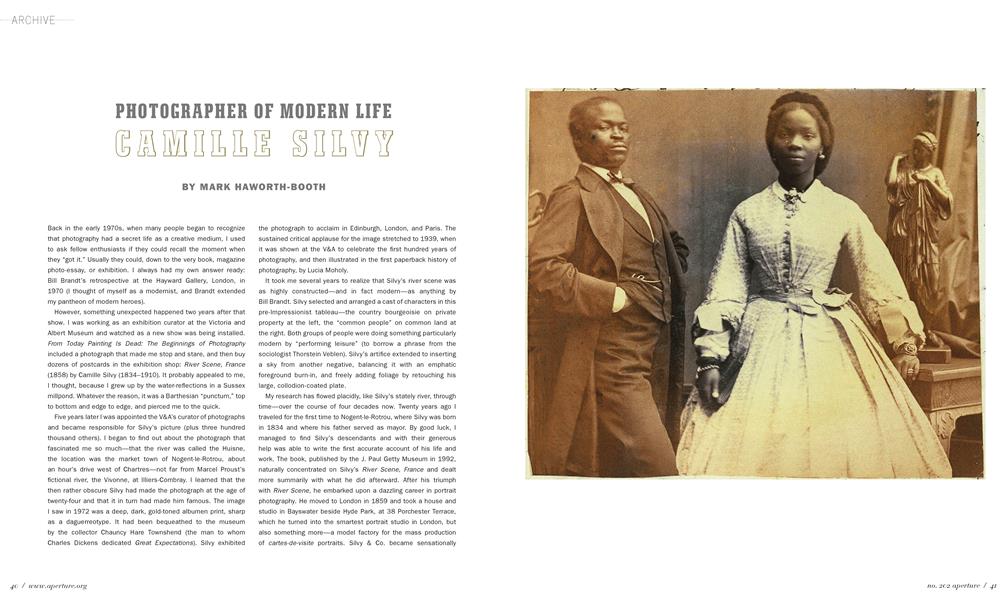

My research has flowed placidly, like Silvy’s stately river, through time—over the course of four decades now. Twenty years ago I traveled for the first time to Nogent-le-Rotrou, where Silvy was born in 1834 and where his father served as mayor. By good luck, I managed to find Silvy’s descendants and with their generous help was able to write the first accurate account of his life and work. The book, published by the J. Paul Getty Museum in 1992, naturally concentrated on Silvy’s River Scene, France and dealt more summarily with what he did afterward. After his triumph with River Scene, he embarked upon a dazzling career in portrait photography. He moved to London in 1859 and took a house and studio in Bayswater beside Hyde Park, at 38 Porchester Terrace, which he turned into the smartest portrait studio in London, but also something more—a model factory for the mass production of cartes-de-visite portraits. Silvy & Co. became sensationally successful. He photographed members of the British royal family and the royal household, the exiled Orléans family and most of the crowned heads of Europe, plus politicians—starting with Britain’s Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston. He photographed diplomats and stars of the theater, as well as clerics, academics, writers, painters, inventors, lawyers, businessmen, and their wives and children.

As it happens, we have a better idea of Silvy’s practice in portrait photography than of any of his nineteenth-century rivals. Almost the entire output of his London studio from 1859 to 1867 was recorded, day by day and sitting by sitting, in a series of large “Daybooks.” Twelve of the thirteen original volumes (one had already been lost) were bought by London’s National Portrait Gallery in 1904. These albums are one of the greatest survivals of nineteenth-century photography. They comprise some seventeen thousand portraits as well as records of the many other areas of photography practiced by Silvy, such as reproducing works of art and manuscripts.

Last year I looked through all the Daybooks four times—although trying to hold seventeen thousand photographs in my mind at the same time proved to be beyond me. However, on each of my tours through the volumes, I noticed different things. We know from a memoir by Félix Nadar that Silvy would, as each new client arrived, pull off a pair of white gloves, toss them into an overflowing basket of used ones, and ostentatiously draw on “an irreproachably new pair.” He did this not only because his clientele was socially exalted but because he would be arranging them physically. The aim was to create an impression of relaxed and graceful nonchalance. However, not even the courtly Silvy (whose early years were spent in the French diplomatic service) could attend to all the intimate arrangements required. For example, a lady in a crinoline would be provided with a footstool on which to place one foot: this would create the contrapposto movement that redeemed the figure from gauche rigidity. I was delighted to come across a portrait in the Daybooks captioned “Mile. Marie.” The reference to her by first name only suggests that she was a member of the studio staff—perhaps it was Mile. Marie who undertook those careful positionings of footstools under crinolines. The Daybooks help one to understand how such studios worked. Cartes-de-visite are often thought of as run-of-the-mill things, neither stamped with individual photographic talent nor containing any degree of liveliness. The truth, I discovered, is rather different. Silvy did not, so far as I can tell, generally use a posing stand. His exposures for these small pictures were often so short as to be virtually instantaneous. Thus, in his 1860 portrait of Louisa Albertina Carnegie, we glimpse a surprisingly décolleté costume but also an apparently spontaneous and mischievous smile.

Silvy was well-known in his day for quantity of production— between 1859 and 1868, when he closed the studio, he and his staff of forty produced over a million prints. However, remarkably, Silvy was also acknowledged for his signature style and attention to detail—the specially painted backdrop or carefully selected accessory.

Something else stood out for me as I trawled the Daybooks. Silvy brought to England a cosmopolitan sensibility that reveals London to be far more international than one might have imagined. His portraits of the exquisitely dressed black couple Mr. and Mrs. Davies, commissioned by Queen Victoria herself in 1862, landed in my conception of High Victorian London with the force of a meteor. Silvy also pioneered a new fusion of portraiture and fashion that reaches its climax, for me, with his image of Miss Valpy (1867). The gift Silvy showed for landscape tableaux was turned to dramatic use as he transformed the confined space of a London glass-house into a series of mansions, boudoirs, state rooms, libraries, parks, and pleasaunces.

Simultaneously, he turned his sitters into modern men and women.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

On Location

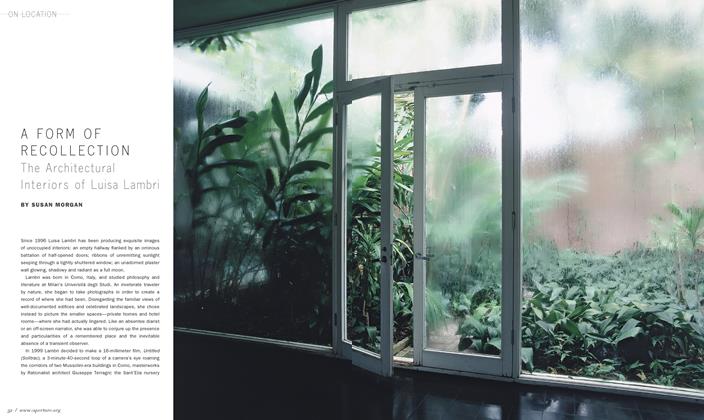

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

Portfolio

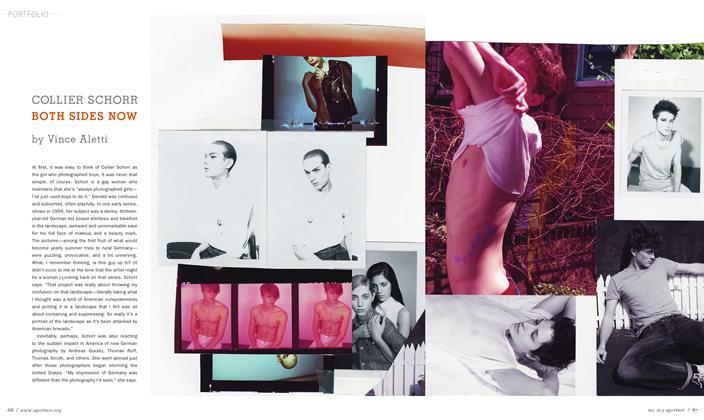

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

Essay

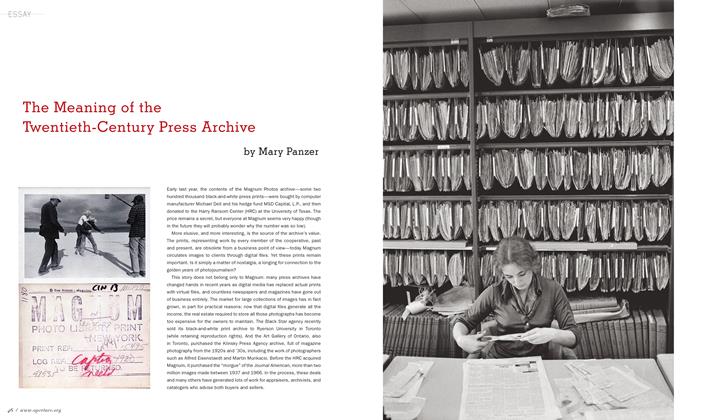

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mark Haworth-Booth

-

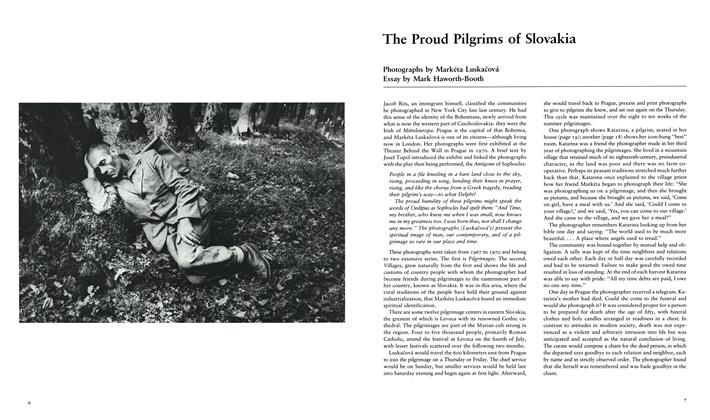

The Proud Pilgrims Of Slovakia

Fall 1983 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

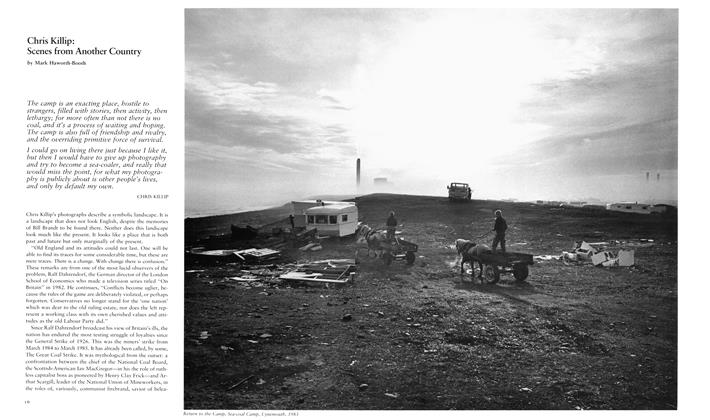

Chris Killip: Scenes From Another Country

Summer 1986 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

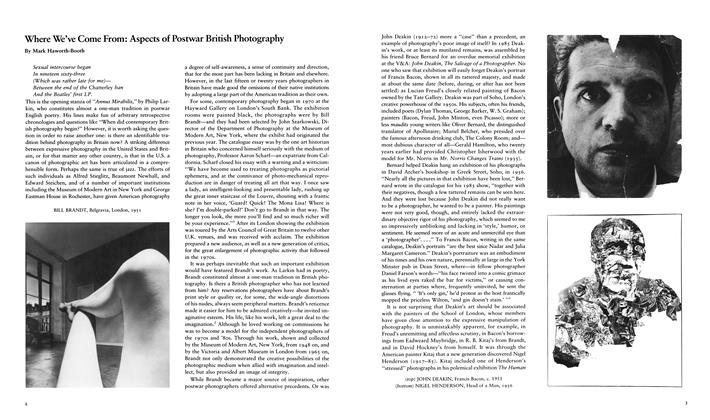

Where We’ve Come From: Aspects Of Postwar British Photography

Winter 1988 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasWilliam Morris: The Earthly Paradox

Winter 1997 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

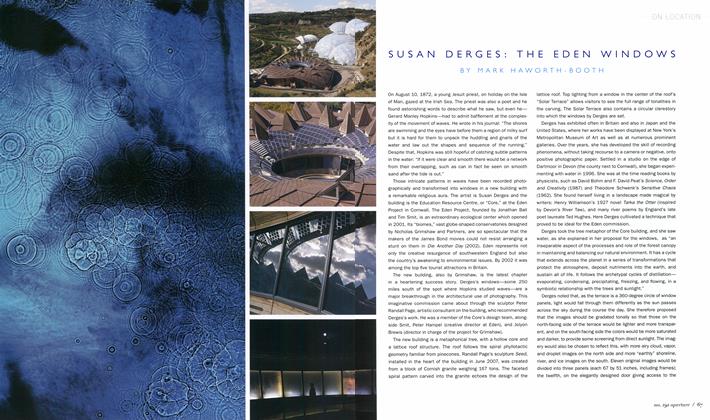

On Location

On LocationSusan Derges: The Eden Windows

Summer 2008 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

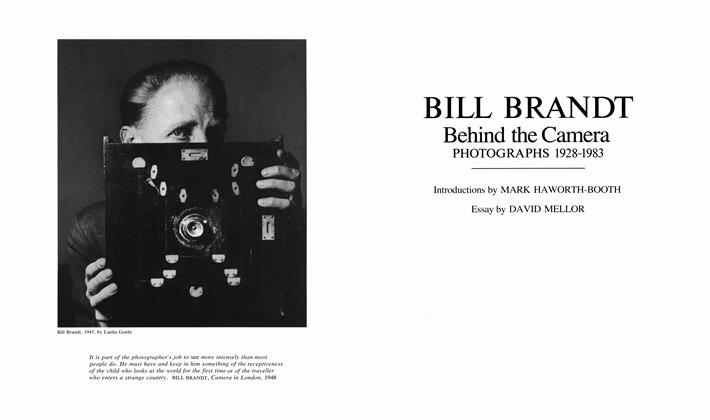

Bill Brandt Behind The Camera

Summer 1985 By Mark Haworth-Booth, David Mellor

Archive

-

Archive

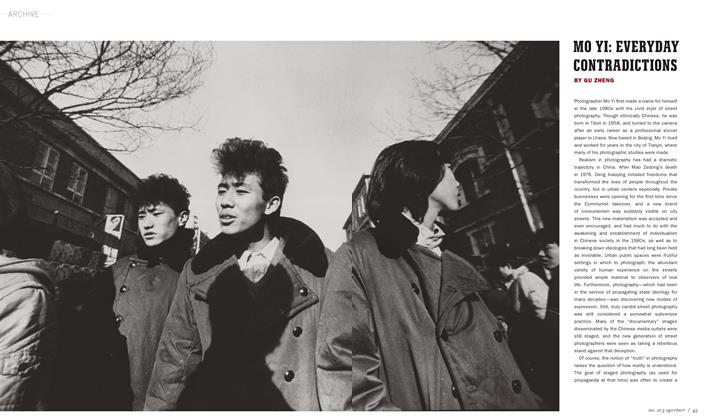

ArchiveMo Yi: Everyday Contradictions

Summer 2011 By Gu Zheng -

Archive

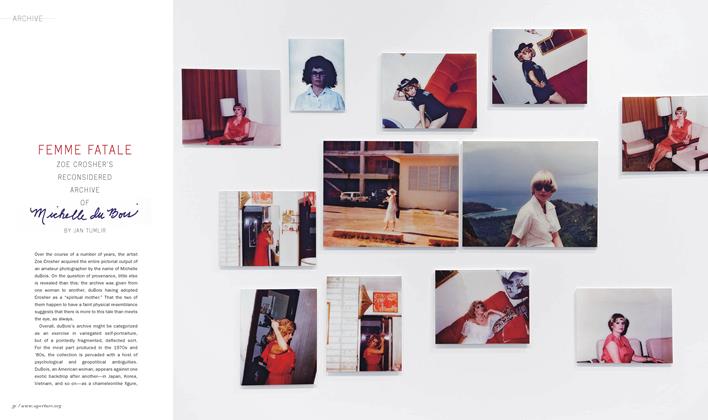

ArchiveFemme Fatale Zoe Crosher's Reconsidered Archive Of Michelle Du Bois

Spring 2010 By Jan Tumlir -

Archive

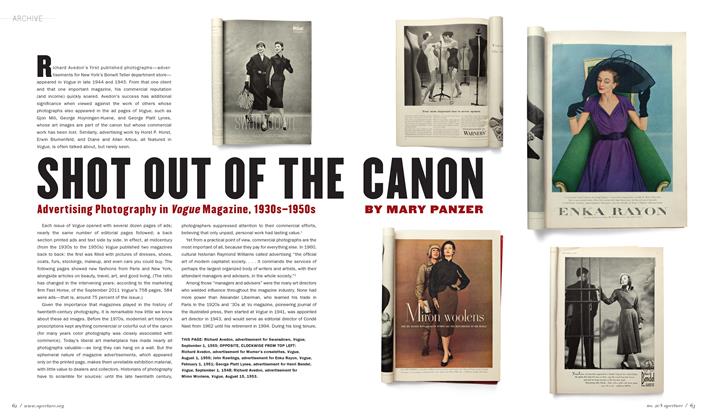

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer -

Archive

ArchiveThe Last Thirty Years Of Mexico

Fall 2010 By Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, David M. J. Wood -

Archive

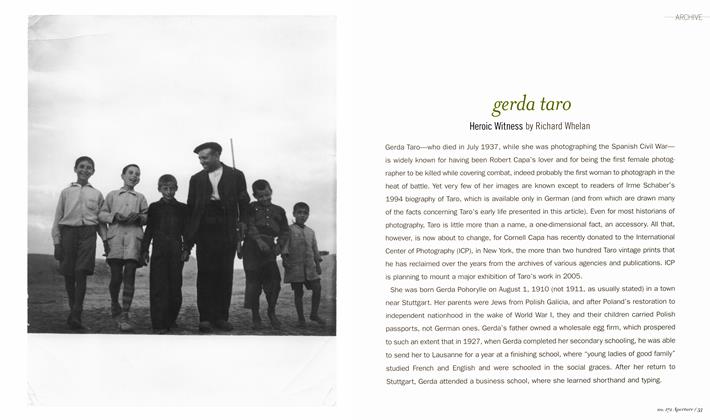

ArchiveGerda Taro

Fall 2003 By Richard Whelan -

Archive

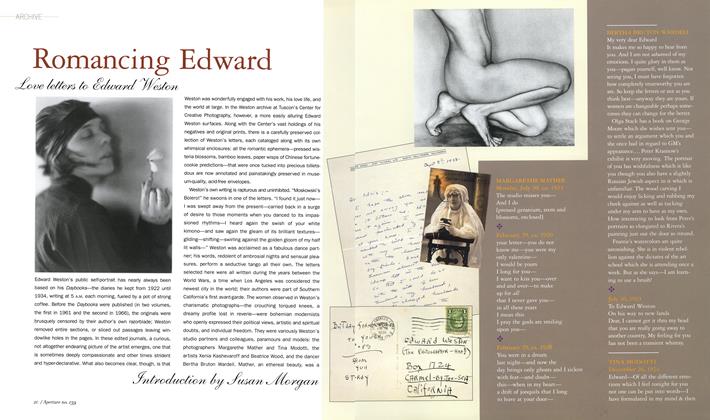

ArchiveRomancing Edward

Spring 2000 By Susan Morgan