Archive

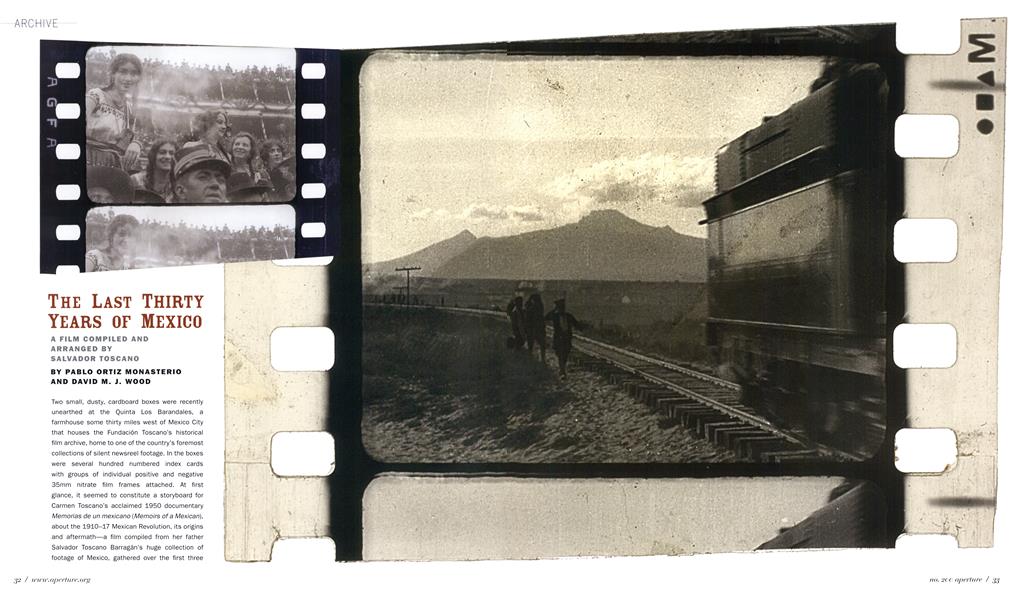

The Last Thirty Years Of Mexico

A FILM COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY SALVADOR TOSCANO

Fall 2010 Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, David M. J. WoodTHE LAST THIRTY YEARS OF MEXICO

ARCHIVE

A FILM COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY SALVADOR TOSCANO

PABLO ORTIZ MONASTERIO

DAVID M. J. WOOD

Two small, dusty, cardboard boxes were recently unearthed at the Quinta Los Barandales, a farmhouse some thirty miles west of Mexico City that houses the Fundación Toscano’s historical film archive, home to one of the country’s foremost collections of silent newsreel footage. In the boxes were several hundred numbered index cards with groups of individual positive and negative 35mm nitrate film frames attached. At first glance, it seemed to constitute a storyboard for Carmen Toscano’s acclaimed 1950 documentary Memorias de un mexicano (Memoirs of a Mexican), about the 1910-17 Mexican Revolution, its origins and aftermath—a film compiled from her father Salvador Toscano Barragán’s huge collection of footage of Mexico, gathered over the first three decades of the twentieth century. But on closer inspection, this photographic index turned out to be something of even greater historical, not to mention aesthetic, significance.

When the engineer Salvador Toscano bought a Lumière cinematograph in 1897, he embarked on a long career as a cameraman, exhibitor, and collector concerned with recording and narrating historical and everyday events through the moving image during one of the most tumultuous periods of Mexico’s modern history. After more than a decade of mixed successes under the regime of the stalwart modernizing dictator Porfirio Díaz, the fortunes of film entrepreneurs such as Toscano took a turn for the better with the outbreak of the revolution in 1910: both urban and rural Mexicans were now hungrier than ever for the realism and immediacy with which the cinematograph brought news from around the country.

Unlike many of his competitors, however, Toscano was not content with simply churning out newsreels to keep up with daily events.

He spent the years of the revolution and the turbulent period that followed building up a vast archive of footage, which he mined for the several versions of his Historia completa de la revolución (Complete history of the revolution), updated numerous times from 1912 until the 1930s: historical compilation documentaries that ran, in some cases, to several hours long.1

Toscano was both a businessman and an ideological advocate of certain revolutionary factions. He was also, in ásense, an heirtothe early Polish champion of film preservation Boleslaw Matuszewski, who, as early as 1898, saw in the medium an exciting “new source of history”: a tool for sharpening human perception that might heighten our comprehension not only of phenomenological reality, but of history itself.

Toscano likely did not share the technological idealism of Matuszewski, who predicted that the visionary powers of the moving image would, in some cases, “eliminate . . . the necessity of investigation and study.”2 But the Mexican film pioneer was undoubtedly a believer in cinema’s power to record and narrate historical events for posterity. While the compilation films of the Russian Revolution (such as Esfir Shub’s 1927 The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty and Dziga Vertov’s 1934 Three Songs About Lenin) have gone down in film history as landmarks of documentary cinema, the innovative epic compilations of Toscano and his contemporaries—in many cases made during the revolution, unlike their Soviet counterparts that were assembled after the event— are all but forgotten, largely due to the failure of the majority of the Mexican Revolution compilation films to survive the ravages of time. The several hundred index cards found at Los Barandales— which refer to a chronologically ordered film enticingly titled Los últimos treinta años de Mexico (The last thirty years of Mexico)— offer a vivid insight into the ways in which revolutionary and postrevolutionary Mexican audiences experienced the greatest social and political upheaval of their time through the new and fast-developing medium of documentary film.

Whether Los últimos treinta años was ever made in the manner suggested by these index cards—which appear to constitute a form of editing script—is uncertain. No records have been found of a film with this title and by 1934, the year that this particular compilation seems to have been planned, the Mexican cinemagoing public’s appetite for historical accounts of the long-finished armed revolution was decidedly on the wane. But more than a simple index to a single film, these bundles of surprisingly wellpreserved cardboard and nitrate constitute a palimpsest—a used and reused parchment on which a whole array of historical compilations, everyday newsreels, and even poetic, existential reflections are inscribed.

Los últimos treinta años seems to have been intended as an update of Toscano’s 1928 compilation Veinticinco años de vida en la historia de México (Twenty-five years of life in Mexican history), which focused on material progress and folkloric celebrations during the final years of the reign of Porfirio Díaz, culminating in the exuberant 1910 commemorations of the centenary of the country’s independence; the political and military events of the 1910-17 conflict; and the long path to pacification in the 1920s, notably marred by Adolfo de la Huerta’s 1923-24 uprising against the postrevolutionary regime.

It is likely that Toscano used this same system of index cards over the years as a way of organizing and planning the material for his compilation films: Veinticinco años emerged from previous film essays, traces of which lie within the script, and this same material formed the basis for Carmen Toscano’s later Memorias de un mexicano. But even as Toscano’s presence is clear in this archive (the texts typed on the index cards are undoubtedly his own), the wide range of title and intertitle designs, originating from a gamut of Mexican and U.S. film entrepreneurs, points to a polyphony of authorships, each with its own view, description, or interpretation of the Mexican conflict.

If Toscano’s political convictions evolved as the Mexican Revolution went on, his historical vision in Los últimos treinta años is mostly consistent in its unreserved admiration for the tragic “Apostle of Democracy,” Francisco Madero, who rose up against the dictator Diaz in 1910, and for the revolutionary leader Venustiano Carranza, whose Constitutionalist faction emerged victorious in 1917. Toscano seems to have had a guarded respect for Diaz himself, the great strategist-, pacifier-, and modernizerturned-tyrant; and a distaste, tinged with a fearful regard, for the popular revolutionaries Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Villa (the latter in particular singled out in the index cards as “capricious and blind,” with a “feline grin”).

But this is not simply a story of leaders, generals, and strongmen: one of Toscano's most remarkable achievements is his circumstantial ability to reveal how momentous historical events cut through the everyday lives of ordinary men, women, and children, whose poses, dress, and appearances lend their own implicit takes on the revolution. We might admire the sleek composition (foreshadowing later Mexican avant-garde photography) of a mass of sombreros whose wearers celebrate

Madero on his triumphant journey to the capital; we might marvel at the elderly indigenous woman Antonia Diaz, smilingly bearing aloft a revolutionary standard in the early days of the conflict. We might reflect on the stark contrast between the innocent hordes of schoolchildren marching patriotically during the 1910 centennial of Independence, and, just a few years later, “Ramón García, the Little Dare Devil Corporal,” standing proudly in front of the camera, one of the countless child soldiers tragically swept along by the revolution. Toscano was not simply a reporter of power struggles: his vocation was marked by a deep commitment to daily life.

Even more immediately striking than the images themselves is the kaleidoscope of colors in which many of the nitrate frames appear. Before the invention of color-sensitive film stock, silentera filmmakers commonly drew on a whole range of techniques to tint their productions, whether with aesthetic, narrative, or simply decorative intent. Flowever widespread this practice may have been, virtually no colored silent-film footage has survived from Mexico. Yet among the four thousand-odd frames in Toscano’s editing script, hundreds of reds, oranges, and yellows—and, less commonly, blues, greens, and pinks—catch our eye, the result of the immersion of the developed positive reel into chemical dyes: testimony that Mexican silent-film theaters exhibiting the events of the revolution were lit up not by a monochrome gray, but by a whole spectrum of hues. The difficulty in establishing a narrative logic to the tinting of the positive frames is compounded by the diverse origins of the material; we cannot tell whether it was Toscano himself, the colleague or competitor from whom he bought the film, or some other intermediary who colored a given frame. Two scenes in particular stand out among them: one showing Porfirio Diaz, portrayed as a venerable old man in his dying days in Parisian exile, and the other featuring the statesman Venustiano Carranza, displaying his various functions as political leader, military strongman, and father. These scenes make powerful use of this now-obsolete but still effective technique to celebrate and dignify these heroes, or antiheroes.

Although the Mexican Revolution, which began before the start of World War I, was the first great conflict to be filmed more or less systematically, we have little idea of just how film audiences of the day lived out this social and political upheaval through cinema. The discovery of Toscano’s editing script not only brings us a step closer to understanding the experiences of those remote spectators, it offers a glimpse of a whole series of epic motion-picture narratives forged over many years with a meticulous attention to detail. At last, perhaps, documentary film may now recognize its debt to Salvador Toscano.©

Notes:

1 Ángel Miquel, Salvador Toscano (Mexico: Universidad de Guadalajara/Gobierno del Estado de Puebla/Unlversidad Veracruzana/Universldad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1997).

2 Boleslaw Matuszewski, “A New Source of History” [1898], Film History 7, no. 3 (1995): 322-24.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

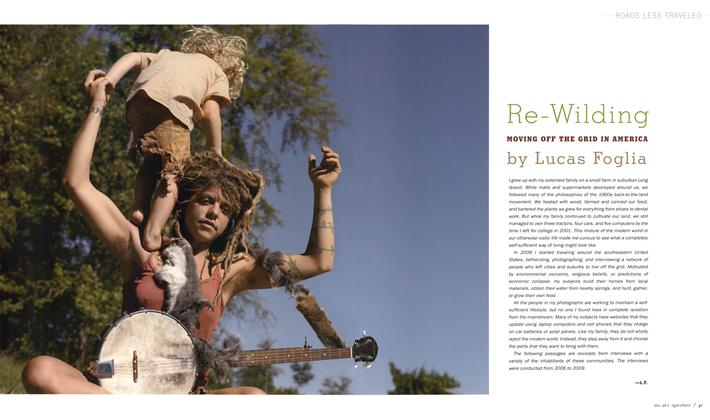

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledRe-Wilding

Fall 2010 By Lucas Foglia -

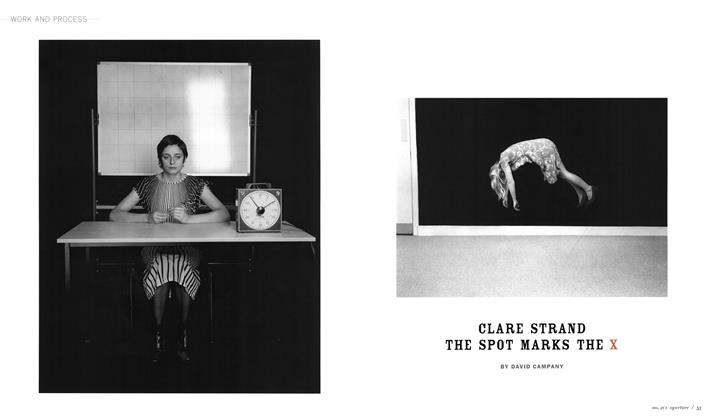

Work And Process

Work And ProcessClare Strand The Spot Marks The X

Fall 2010 By David Campany -

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Calamity Of Heart

Fall 2010 By E. L. Doctorow -

Witness

WitnessHeroes Of The Storm: Five Years After Katrina

Fall 2010 By Deborah Willis -

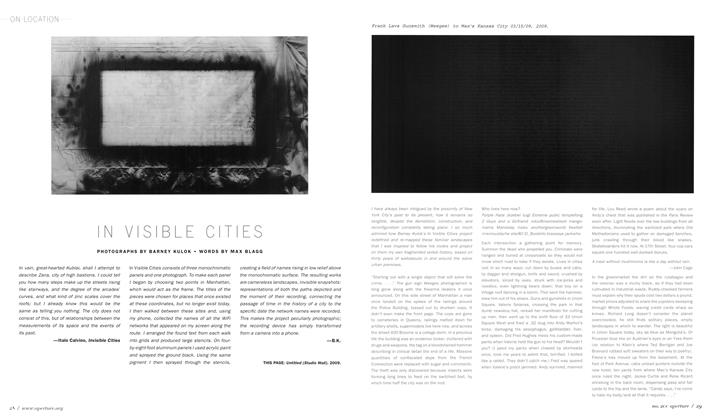

On Location

On LocationIn Visible Cities

Fall 2010 By Max Blagg -

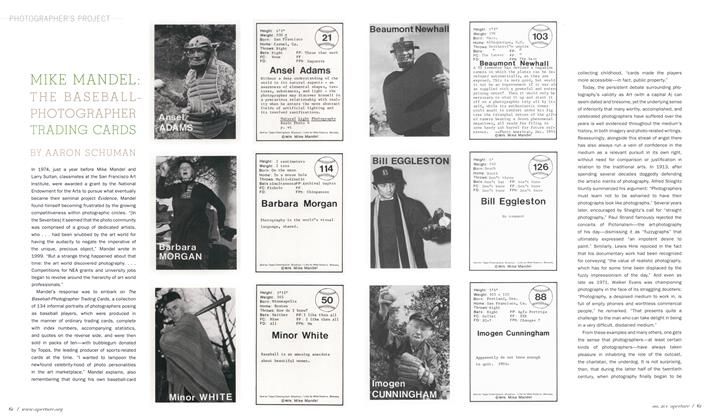

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectMike Mandel: The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards

Fall 2010 By Aaron Schuman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Archive

-

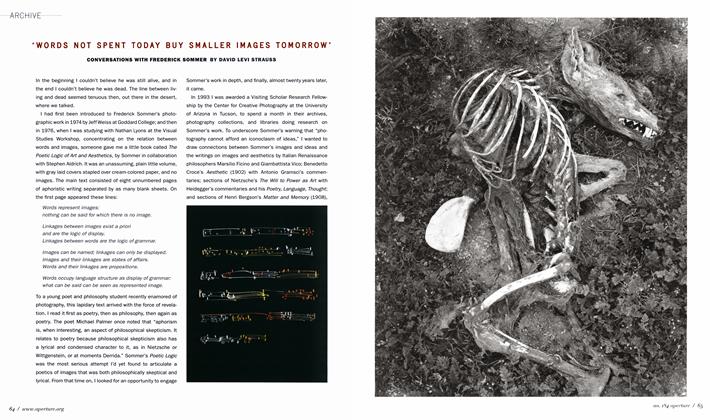

Archive

Archive"Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow"

Fall 2006 By David Levi Strauss -

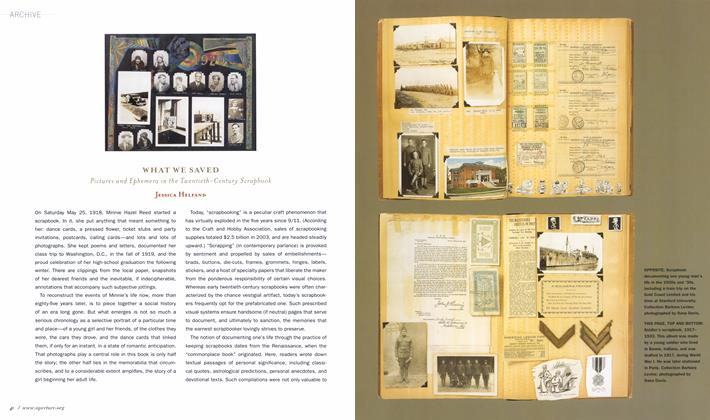

Archive

ArchiveWhat We Saved

Summer 2006 By Jessica Helfand -

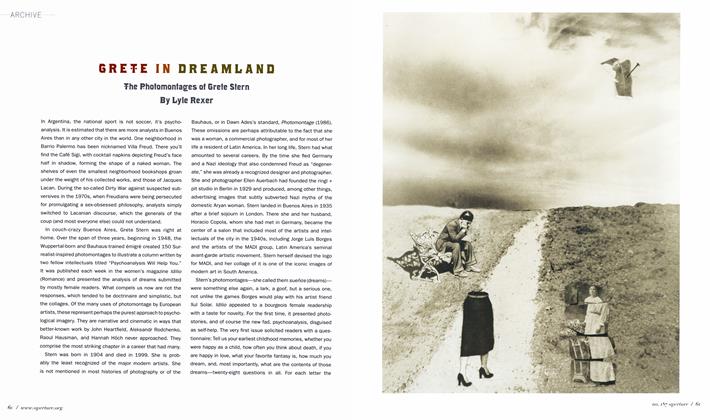

Archive

ArchiveGrete In Dreamland

Summer 2007 By Lyle Rexer -

Archive

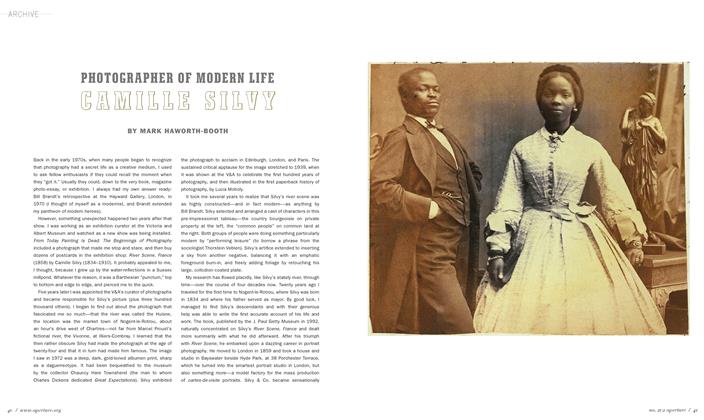

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Archive

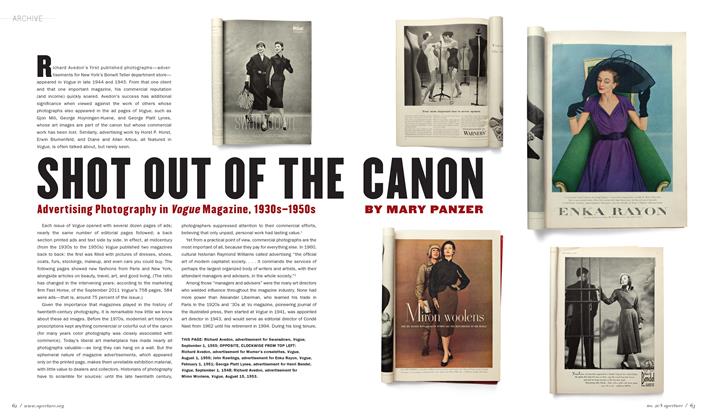

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer -

Archive

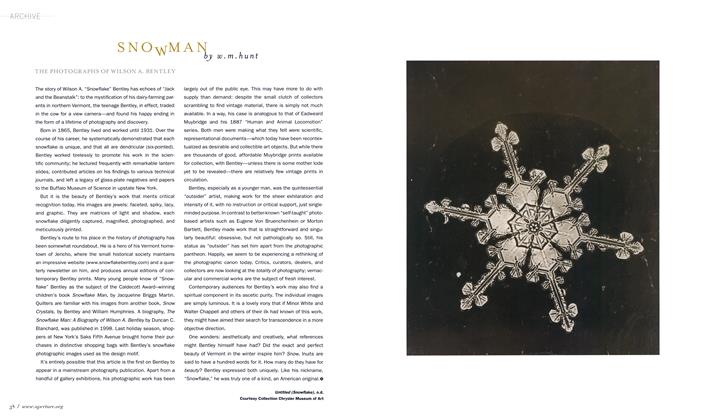

ArchiveSnowman: The Photographs Of Wilson A. Bentley

Spring 2006 By W.M.Hunt