On Location

A Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 Susan MorganA FORM OF RECOLLECTION The Architectural Interiors of Luisa Lambri

ON LOCATION

SUSAN MORGAN

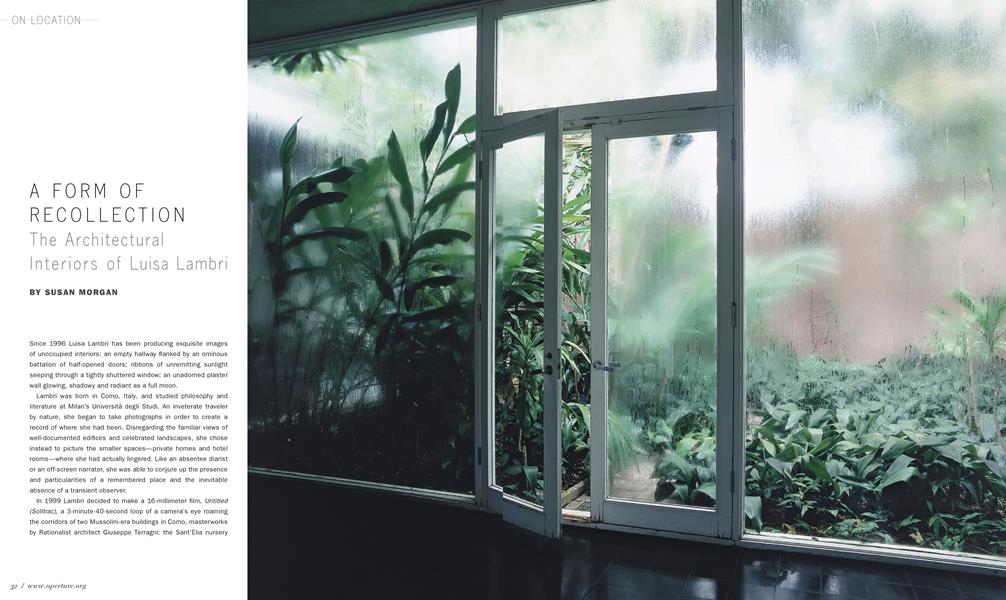

Since 1996 Luisa Lambri has been producing exquisite images of unoccupied interiors: an empty hallway flanked by an ominous battalion of half-opened doors; ribbons of unremitting sunlight seeping through a tightly shuttered window; an unadorned plaster wall glowing, shadowy and radiant as a full moon.

Lambri was born in Como, Italy, and studied philosophy and literature at Milan’s Université degli Studi. An inveterate traveler by nature, she began to take photographs in order to create a record of where she had been. Disregarding the familiar views of well-documented edifices and celebrated landscapes, she chose instead to picture the smaller spaces—private homes and hotel rooms—where she had actually lingered. Like an absentee diarist or an off-screen narrator, she was able to conjure up the presence and particularities of a remembered place and the inevitable absence of a transient observer.

In 1999 Lambri decided to make a 16-millimeter film, Untitled (Solitrac), a 3-minute-40-second loop of a camera’s eye roaming the corridors of two Mussolini-era buildings in Como, masterworks by Rationalist architect Giuseppe Terragni: the Sant’Elia nursery school (1937), Lambri’s kindergarten alma mater; and the Casa del Fascio (1932-36), an elegant International Style palazzo originally created to house Fascist party offices and host political rallies. Although Lambri filmed each Terragni building in what she has described as “a straightforward documentary style,” her editing merged the two buildings into a single frame, blurring the distinctions between the sites and delivering a newly contrived image, a visual rendition of an invented space. In Lambri’s film loop, a clearly defined but virtually nonexistent place appears, as palpable and unreliable as a memory.

Lambri works in a boundlessly international tradition: a kind of urbane itinerancy that is common among many of today’s artists. Although she is based primarily in Milan, her ongoing project, photographing details of architecturally significant spaces, is both far-flung and narrowly focused. She has been awarded artist residencies in the United States, Brazil, England, Finland, Italy, Japan, and Sweden. A quick sampling of her photographic subjects—including R. M. Schindler’s Kings Road house (Los Angeles, 1922), Lina Bo Bardi’s Casa de Vidro (Säo Paulo, 1951), Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House no. 22 (Los Angeles, 1960), and the House in Plum Grove (Tokyo, 2003, by the firm SANAA, recent Pritzker Prize laureates)—could rival Galinsky, the informed online guide to the world’s great modern buildings. When architect Kazuyo Sejima, SANAA partner and director of the 2010 Venice Architecture Biennale, commissioned Lambri to participate in the exhibition People Meet in Architecture, she presented a selection of photographs focused on the varying shades of natural green that frame, surround, and spring up around well-known buildings. In an interview with architect Stefano Mirti for the Italian design magazine Abitare, Lambri confessed that she has always “used architecture to talk about something else.” She and Mirti first met in 1996 when he organized a tour of Turin for her. “It was a proper architecture course,” she recalled, “a whole series of afternoons spent visiting some pretty strange places: derelict factories, the basements of the Molinette hospital, Villa Gualino, the DuParc.” The built environment that Mirti clearly understood as architecture, Lambri said, is what she had previously called simply “place”: quotidian environments, rather than highly premeditated habitats.

Lambri often refers to her photographs as “self-portraits”— although they are not, in any traditional sense—and her pursuit of modern domestic architecture provides her with an ideal framework. Her photographs of spaces deliver an experiential record, an account of individual perception occurring in a rigorously intentioned setting, a glimpse into the sensations of place and the passage of time. Self-portraiture is, of course, a pliable and enormously broad subject for an artist, suggesting untold interpretations ranging from ruthless pencil drawings to hyperbolic performances. Gina Pane, Cindy Sherman, and Francesca Woodman are artists that Lambri generally cites as influences on her own work. Beginning in the late 1970s, these artists finessed the realm of self-portraiture into a staging ground for questions and attitudes about feminism, psychoanalysis, the body, and cultural stereotypes. Many of the scenes they portrayed occurred within the confines of a domestic setting. In Sherman’s series of Untitled Film Stills (which she began in 1977), a single woman variously peers out through draperies, sits poised in an open tenement window, or leans dejectedly against a spattered kitchen door. Woodman photographed herself disappearing into windows and mirrors, pressed against old mottled walls and concealed beneath sheets of decrepit wallpaper. Pane’s 1968 film Solitrac provided the inspiration (and subtitle) for Lambri’s later film: in Pane’s piece, a woman, alone in an apartment, constantly opens and closes doors, but is never able to get out. These constructed images, the forceful and disquieting rooms, hint at Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams-, in the dream imagination, the house is a symbol of identity and the human body, and a room is a woman.

As Lambri began to photograph interiors, she examined how you might find yourself within a space and what it is that you feel once you are there. Space, the writer Esther McCoy observed, is actually one of architecture’s essential building materials. When McCoy’s landmark book, Five California Architects, was published in 1960, her approach to architectural writing was met with skepticism; academic architectural historians had long focused their discussions on building façades and exterior construction. McCoy, a literary writer and non-academic, looked by contrast at floor plans and how people move through interior spaces—and through these actions and elements she recognized the compelling plot of modern architecture. This viewpoint is replicated in Lambri’s photographs, where the façades of buildings never appear. Her camera’s eye is deliberately subjective, taking in odd angles, junctures, thresholds, the subtle but revelatory shifts of daylight, how spaces flow between indoors and out, and where nature might collide with architecture.

By focusing entirely on the view from within, Lambri’s work falls far outside the established category of architectural photography. Even the most iconic structures of twentieth-century architecture— Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye in Poissy, France; Gerrit Rietveld’s Schröder House in Utrecht, Netherlands—appear unrecognizable and abstract in her photographs. She looks at inhabited spaces, the private lives of houses, and seeks out details, overlooked or evocative elements and unanticipated situations. At Richard Neutra’s Strathmore Apartments (Los Angeles, 1937), she photographed bands of light seeping through the Venetian blinds, echoing the rhythm of Neutra’s design: alternating between solids and air and always insistently horizontal. At Philip Johnson’s Menil House (Houston, 1950), a low-slung brick building that presents a windowless façade to the street, Lambri documented an interior courtyard as a thunderstorm approached. A door is slightly ajar and the glass walls are clouded white with humidity. The courtyard garden is tropical, damp as a terrarium and overgrown with ferns, palms, and banana trees. The garden appears otherworldly, a lost planet drifting toward the interior of cool steel and gleaming black tile floors.

Lambri’s photographs are unstaged; she doesn’t move furniture or add objects. She shoots hundreds of large-format photographs onsite and then scrupulously edits her selection. During that process, however, she digitally manipulates the images, adjusting the light and contrast in order to create a truer feeling, her own poetic truth, of the place being portrayed.

Being There, Lambri’s 2010 exhibition at the Hammer Museum of the University of California at Los Angeles, featured a series of photographs taken at John Lautner’s Sheats Goldstein residence (Los Angeles, 1963). Built into a steep hillside, Lautner’s house is cavernous and imposing, an angular concrete-and-steel shelter with low timbered ceilings and vast glass walls that survey a nearly endless prospect. After studying the interior, Lambri turned her back to the spectacular view. Looking up through the house’s small skylights, she photographed a more specific and intimate vista: a patch of sky, sunlight, shadows, and a tracery of leafy branches. In an essay written to accompany that exhibition, curator Alma Ruiz compares Lambri’s interest in the phenomenal aspects of a site to the work of artists such as Larry Bell and Robert Irwin—proponents of the Light and Space movement that started in California in the late 1960s, espousing a reductivist approach to art-making, challenging viewers’ perceptual experience and questioning the artist’s need to produce material objects. Lambri’s work and her experiential approach certainly evoke questions about visual perception and physical sensation, but her decision to make photographs seems to run a zigzag course leading much further back into art history and the origins of photography.

Through her photographs, Lambri aims to capture light, shadows, imminent storms, and ephemeral experience. Looking up through a modernist skylight, she photographs a lacy sunlit pattern of leaves and branches floating in an illuminated and unreadable space. It is an image that recalls nineteenth-century cyanotypes—such as the stark and wondrously luminous algae studies produced by Anna Atkins in the 1840s. Light, Lambri’s work reminds us, has always been photography’s subject.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Portfolio

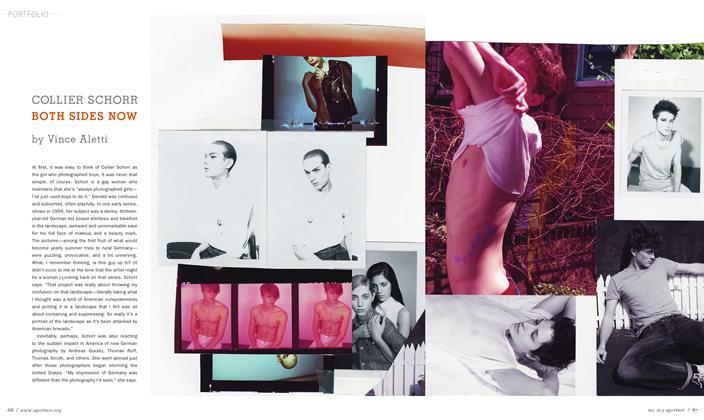

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

Essay

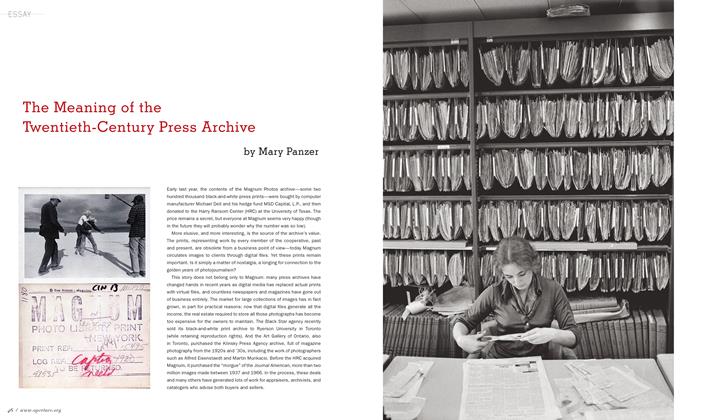

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Archive

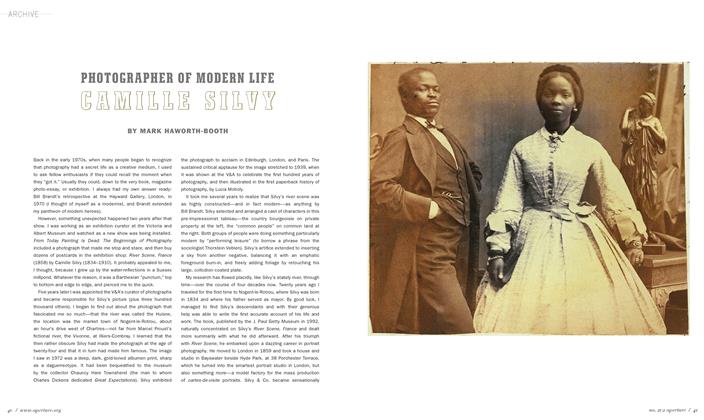

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Susan Morgan

-

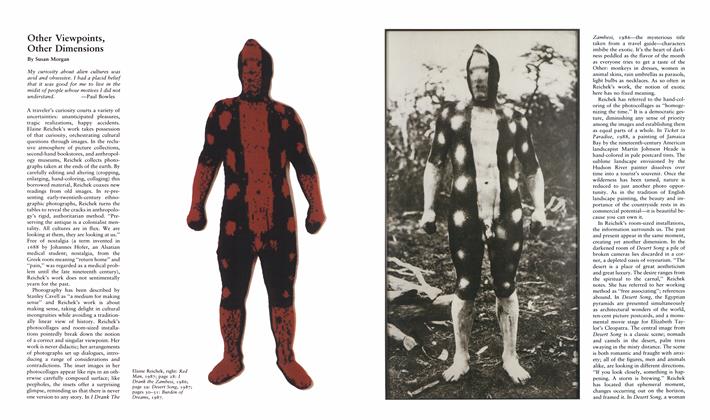

Other Viewpoints, Other Dimensions

Early Summer 1990 By Susan Morgan -

Weston's Portraits

Summer 1995 By Susan Morgan -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasTina Modotti: Photographs, Sarah M. Lowe

Summer 1996 By Susan Morgan -

Archive

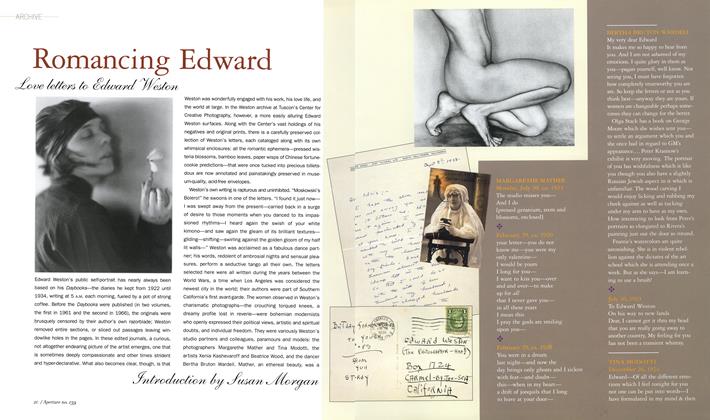

ArchiveRomancing Edward

Spring 2000 By Susan Morgan -

Reviews

ReviewsLorna Simpson

Winter 2006 By Susan Morgan -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Goat's Dance: Photographs By Graciela Iturbide

Fall 2008 By Susan Morgan

On Location

-

On Location

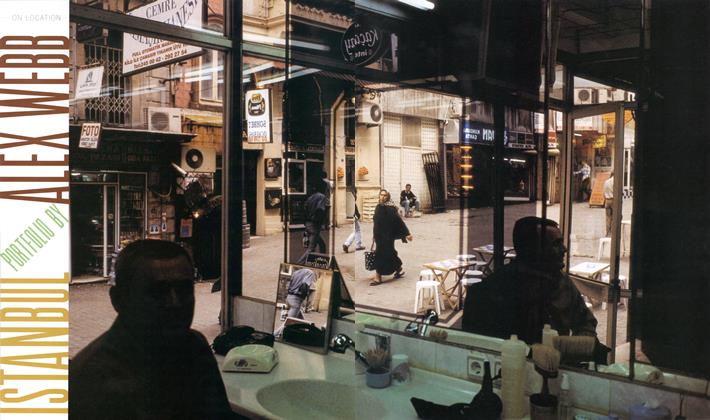

On LocationIstanbul Portfolio By Alex Webb

Winter 2005 -

On Location

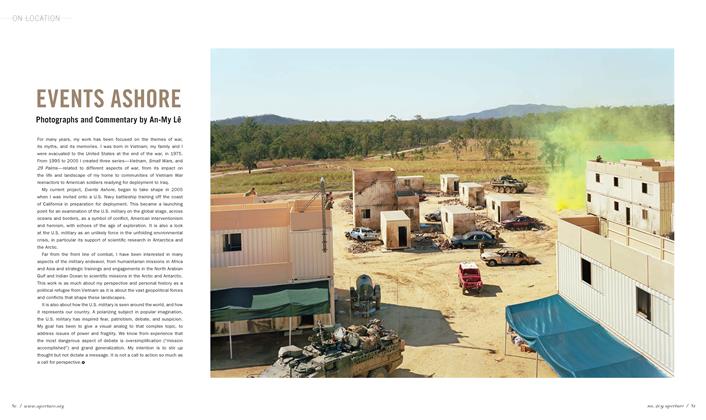

On LocationEvents Ashore

Winter 2012 By An-My Lê -

On Location

On LocationListening To Photography The Silence Of Edgar Martins

Fall 2006 By David Campany -

On Location

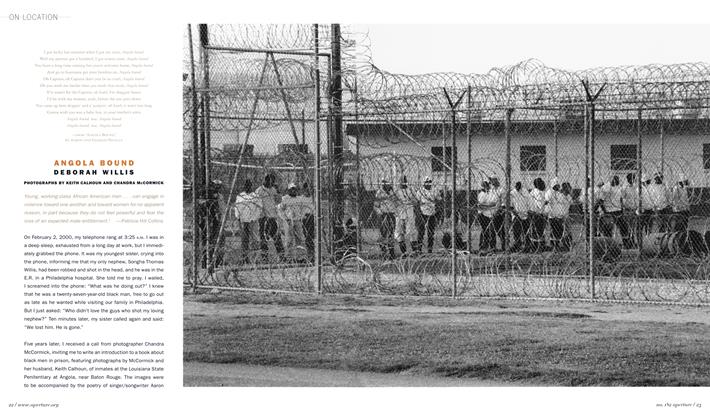

On LocationAngola Bound

Spring 2006 By Deborah Willis -

On Location

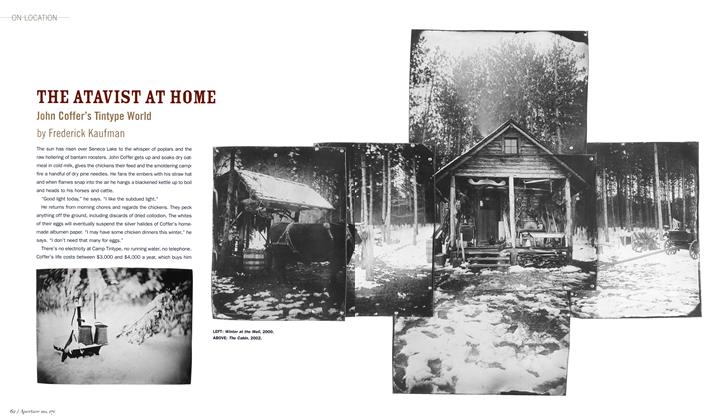

On LocationThe Atavist At Home: John Coffer's Tinytpe World

Spring 2003 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

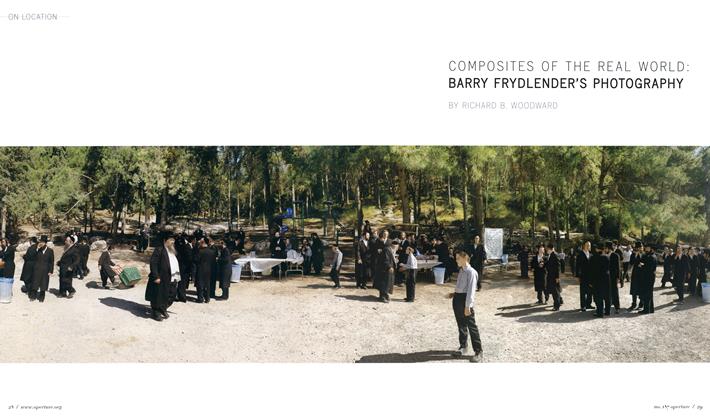

On LocationComposites Of The Real World: Barry Frydlender's Photography

Summer 2007 By Richard B. Woodward