The Meaning of the Twentieth-Century Press Archive

ESSAY

Mary Panzer

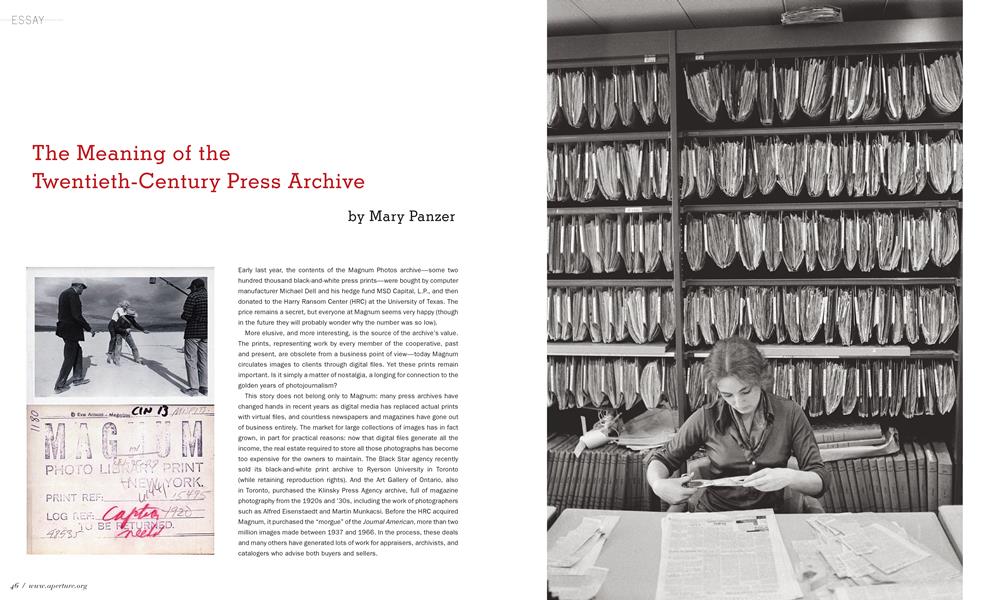

Early last year, the contents of the Magnum Photos archive—some two hundred thousand black-and-white press prints—were bought by computer manufacturer Michael Dell and his hedge fund MSD Capital, L.P., and then donated to the Harry Ransom Center (HRC) at the University of Texas. The price remains a secret, but everyone at Magnum seems very happy (though in the future they will probably wonder why the number was so low).

More elusive, and more interesting, is the source of the archive’s value. The prints, representing work by every member of the cooperative, past and present, are obsolete from a business point of view—today Magnum circulates images to clients through digital files. Yet these prints remain important. Is it simply a matter of nostalgia, a longing for connection to the golden years of photojournalism?

This story does not belong only to Magnum: many press archives have changed hands in recent years as digital media has replaced actual prints with virtual files, and countless newspapers and magazines have gone out of business entirely. The market for large collections of images has in fact grown, in part for practical reasons: now that digital files generate all the income, the real estate required to store all those photographs has become too expensive for the owners to maintain. The Black Star agency recently sold its black-and-white print archive to Ryerson University in Toronto (while retaining reproduction rights). And the Art Gallery of Ontario, also in Toronto, purchased the Klinsky Press Agency archive, full of magazine photography from the 1920s and ’30s, including the work of photographers such as Alfred Eisenstaedt and Martin Munkacsi. Before the HRC acquired Magnum, it purchased the “morgue” ofthe Journal American, more than two million images made between 1937 and 1966. In the process, these deals and many others have generated lots of work for appraisers, archivists, and catalogers who advise both buyers and sellers. Institutions housing press archives include large libraries dedicated to providing access to information (like the Library of Congress), university-based libraries (like the HRC), and private collecting institutions (like the Getty); the companies that created the archives (e.g. Time-Life and the New York Times)] and, more recently, companies that have acquired archives for profit. The role of the institution is simple: to care for the objects and make them accessible to others. The Magnum prints have already been cataloged and housed in acid-free boxes in temperaturecontrolled rooms. Understanding the need for such caretaking is relatively new. When Corbis purchased Bettmann Archive in 1995, a tiny fraction of the archive’s sixteen million images were promptly scanned, the originals were moved from file cabinets on a floor in a New York office building to Iron Mountain, an archival storage facility near Pittsburgh, 220 feet below ground in a former limestone mine where temperature and humidity conditions are nearly perfect. Loudly bemoaned at the time, Corbis’s move now appears very generous; it acquired Bettmann long before buying images on the Internet had become practical and inexpensive. Today Corbis encounters more competitors than Bettmann ever did, and claims to have always run at a loss.

In 1859, Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced Americans to a new medium with his now well-known essay “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” in which he imagined a vast archive of images—“an enormous collection of forms that. . . will have to be classified and arranged in vast libraries as books are now.” His vision ends with a nihilistic flourish:

Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In fact, matter as a visible object is of not great use any longer, except as the mould on which form is shaped. Give us a few negatives of a thing worth seeing, taken from different points of view, and that is all we want of it. Pull it down or burn it up. . . . There is only one Coliseum or Pantheon, but how many millions of potential negatives have they shed. . . . since they were erected! Matter in large masses must always be fixed and dear; form is cheap and transportable. We have got the fruit of creation now, and need not trouble ourselves with the core.

Holmes’s cheerful program of destruction prefigures the replacement of old periodicals with microfilm copies, of library card catalogs with digital records. We could even credit him with envisioning the Kindle—allowing us to demolish whole library buildings and their contents without regret.

Fascination with the archive itself, as an institution, a construction, and a myth, has generated an enormous body of literature. When Jacques Derrida declares that “nothing is less sure, nothing is less clear today than the word archive,” it is hard not to laugh. Following the work of Michel Foucault, scholars of photography have recognized how the archive governs the meaning of the images inside it—an important point, because no photograph generates its own meaning. Individual photographs acquire many different meanings in the course of moving from government report to private attic to flea market to museum wall. Art scholarship asks who made it, finds an author, and places the image within the scholarly canon—a kind of intellectual archive. Historians and critics such as Allan Sekula and Sally Stein, who are interested in the image as it functions within a social context, ask why it was made, what function did it serve, and whose interests the archive represents. More recently, Robin Kelsey and Georges Didi-Huberman have built on these ideas to identify both agencies of power and the ways in which the subjects of their gaze resist control.1

For all kinds of scholars, the Magnum archive and its contents are a treasure. Prints by many canonical cooperative members remain relatively rare; not surprising, since their work was originally made for publication in the press. But a larger appeal lies in the information prints acquired while circulating to magazines and publishers, such as stamps, inscriptions, instructions to clients and printers, notes from art directors, Magnum staffers, and sometimes even the photographer. These ephemeral notes create a history of the actual print, and of the publishing industry for which such circulating images were essential. These prints have little or no appeal on the art market, which prefers its images unique and prints pristine. But scholars welcome the inscriptions as a sign of authenticity, and something more, a testament to “its unique existence at the place where it happens to be”—the definition Walter Benjamin used to define “aura.”

The Ransom Center’s ambitions reach far beyond the acquisition of important photographs—it seeks to acquire the history of the world. As the Center’s press release brags: “A Magnum photographer was present at almost every significant world event—D-Day, the civil rights movement, the rise of Fidel Castro, [and] portrayed almost every celebrity and newsmaker.” The New York Times called the archive a “collective photobank of modern culture.”

Yet to celebrate the fact that the archive has value because “significant world events” and “every celebrity and newsmaker” of the second half of the twentieth century were captured by Magnum photographers seems naïve. In fact, those events and celebrities were largely created by the media, and Magnum contributed to that process in important ways. Guy Debord, Pierre Bourdieu, and others have discussed the abstract ways in which our “Society of the Spectacle” consumes media versions of events and individuals (are celebrities individuals?) that cannot exist outside their photographic representation in still pictures. The archive preserves not the events themselves, but the matter from which those constructions were made.

In his extended 1980 essay, “Within the Context of No Context,” George W. S. Trow discusses the change in perception brought on by trust in television specifically, and media in general, and the effect of that change on middle-class American society. For Trow, we live in a world where all information is packaged for a single standard: small, personal, controllable, agreeable, which provides no opportunity for argument. We reach for consensus rather than justice, and value popularity over quality because quality would require making a judgment, which must be carried out by an authority that no longer exists. For Trow, our society has a “hunger for history” that is expressed in two basic forms: the obsession with artifacts from one’s own childhood, and the longing for artifacts from someone else’s privileged adulthood. For a population that increasingly identifies history with old pictures and TV shows, the past has become a cool collectible. Seen in this light, the Magnum archive offers endless opportunities.

It is true that, at least when it comes to Western culture, our knowledge (and now our memory) of historical events has been shaped by the way they appeared in picture magazines such as Life, Look, Paris-Match, and the London Sunday Times, where an enormous audience found images, information, and entertainment in the decades before television prevailed. Editor and critic Christian Caujolle supports that view, identifying the function of photojournalism as a social one, to provide “the documents essential to our collective memory.” French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs invented the concept of “collective memory” in the 1920s—an idea so strong that it has become part of our own collective understanding. Very simply, collective memory refers to both content and structure, the framework within which we construct our perceptions and memories as well as the stuff we remember. As Halbwachs conceives of it, memory must be constantly remade; it “is not preserved but is reconstructed on the basis of the present.”

Seen this way, photojournalism—and especially the images that reside in archives—become the essential source for that collective activity, the material we use, as Halbwachs says, “to reconstruct an image of the past which is in accord, in each epoch, with the predominant thoughts of the society.” Not only because we share access to the images, but, through the volume of images and the information that accrues within their stamps and creases, we can start to understand how images functioned in the world made by magazines. That image bank binds a generation together, and connects one generation to the next.

The photographic archive is not an inert museum vitrine that displays the practice and function of photojournalism from the past. It reveals the contingent nature of this information, which most of the early viewers knew without being told. The photographers, darkroom technicians, picture editors, and even some readers could measure the photographs against what they actually saw, and knew what had been left out. Those first viewers knew how images could shape events, but did not replace them.

All those unpublished, neglected, and forgotten photographs, and all the data they preserve, allow us to glimpse how photojournalism failed then and, more important, continues to fail today.

But as historian Carlo Ginzburg explains, the recognition of this failure is where real history begins. “Sources are neither open windows, as the positivists believe, norfences obstructingvision, as the skeptics hold: if anything, we could compare them to distorting mirrors.” The meaning of any image is certainly constructed by the observer, “but construction ... is not incompatible with proof, the projection of desire, without which there is no research, is not incompatible with the refutations inflicted by the principle of reality. Knowledge (even historical knowledge) is possible.”

At this moment, when digital and silver-based images coexist, and we can find witnesses to describe every step of this technological transformation, the archive, with its ability to preserve ample evidence of distortions inherent to the medium, makes it possible to start to write a history of photojournalism as practiced in the age before digital media made its products obsolete.©

NOTES

1. See Robin Kelsey, Archive Style: Photographs and Illustrations for U.S. Surveys, 1850-1890 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), and Georges Didl-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz (2003); trans. Shane B. Lillis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

The author wishes to thank Sarah Morthland, Steven Kasher, Beth Iskander, and Beverly Brannan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

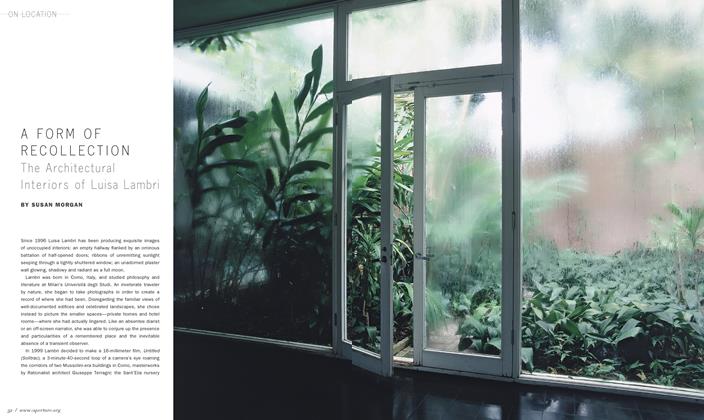

On Location

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

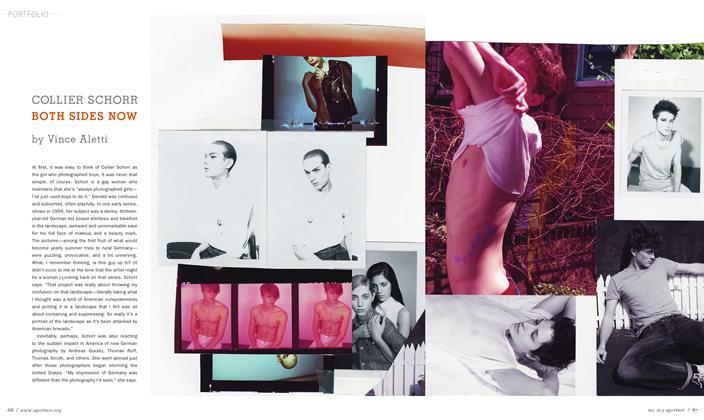

Portfolio

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Archive

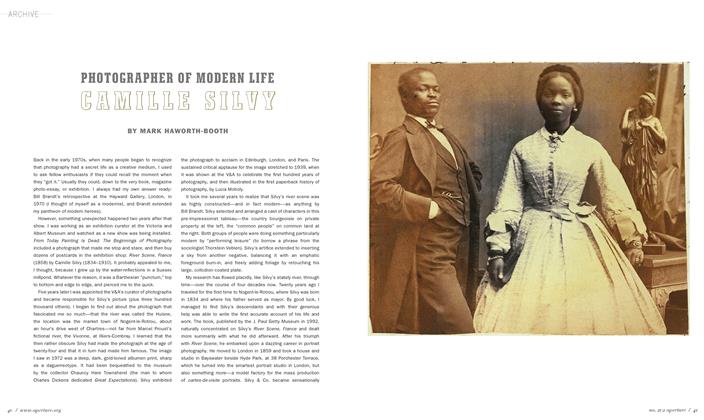

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mary Panzer

-

Witness

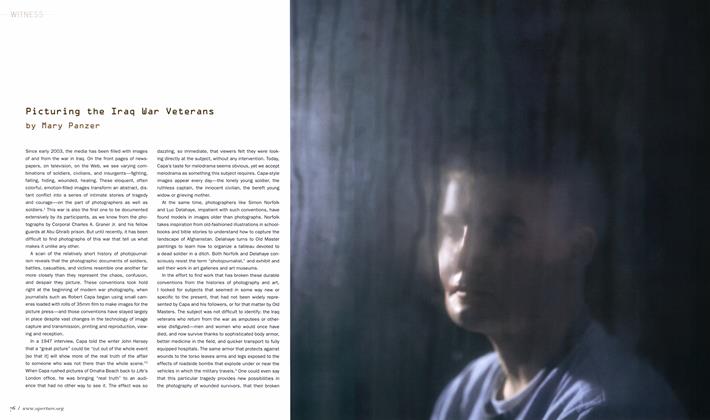

WitnessPicturing The Iraq War Veterans

Summer 2008 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

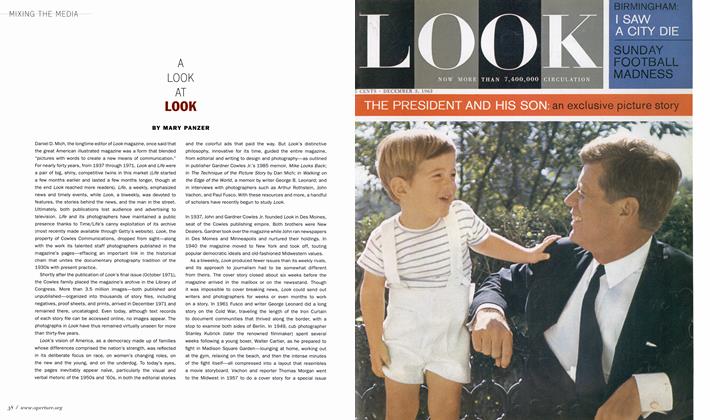

Mixing The MediaA Look At Look

Summer 2009 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaOn Holiday

Spring 2010 By Mary Panzer -

Essay

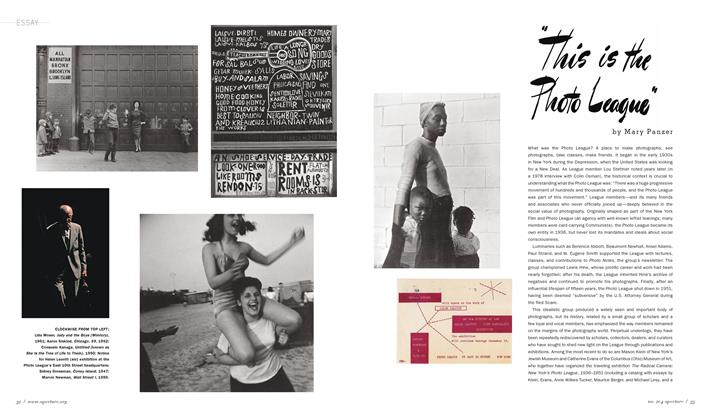

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

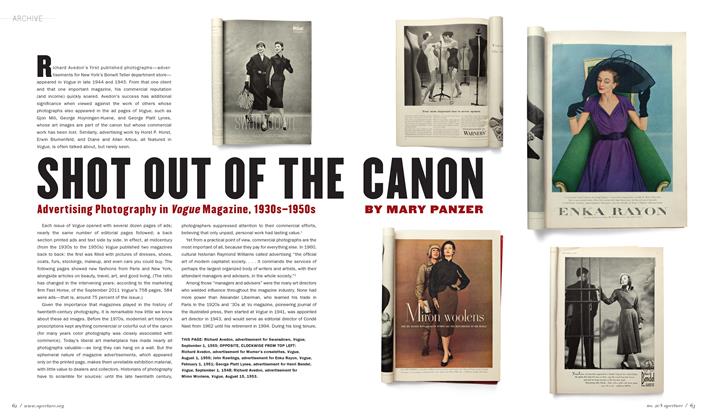

Archive

ArchiveShot Out Of The Canon

Fall 2012 By Mary Panzer -

What Matters Now?

What Matters Now?Rediscovering Hine

Spring 2014 By Mary Panzer

Words

-

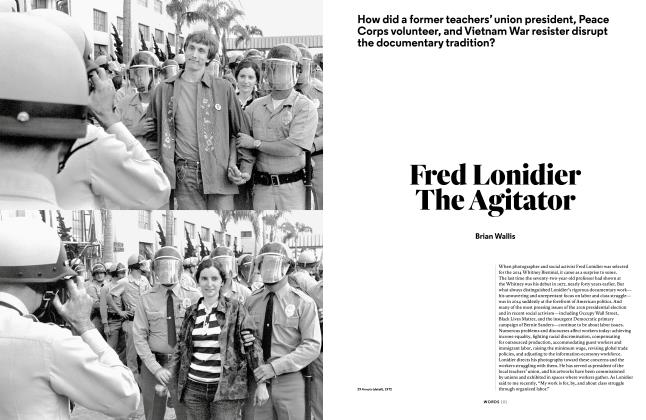

Words

WordsFred Lonidier: The Agitator

Spring 2017 By Brian Wallis -

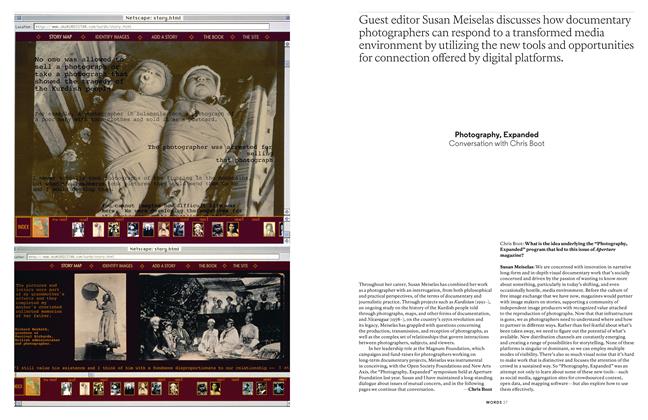

Words

WordsPhotography, Expanded

Spring 2014 By Chris Boot -

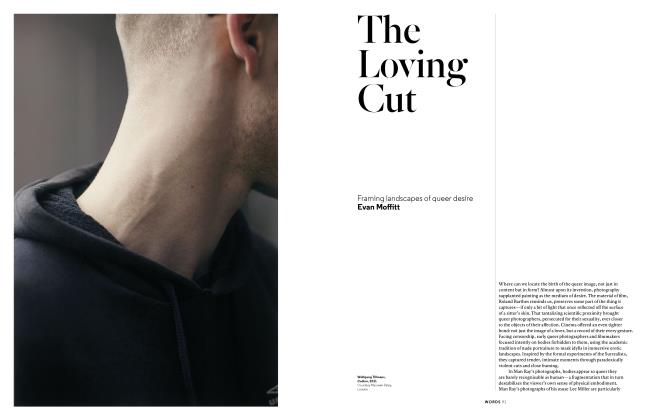

Words

WordsThe Loving Cut

Summer 2018 By Evan Moffitt -

Words

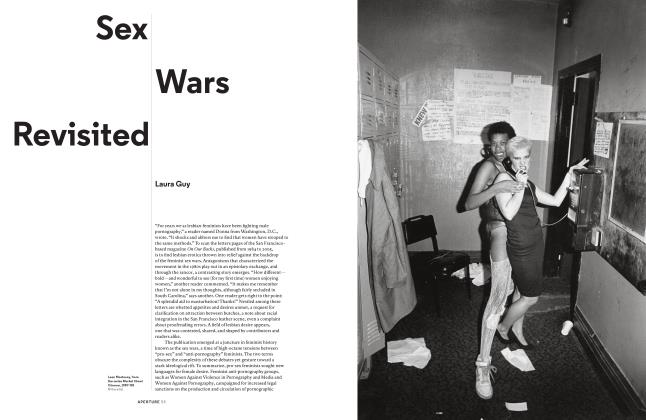

WordsSex Wars Revisited

Winter 2016 By Laura Guy -

Words

WordsDomestic Labor

Winter 2018 By Lynne Tillman, Justine Kurland -

Words

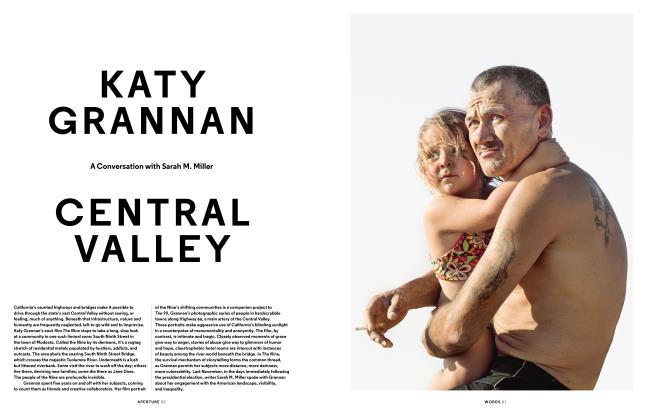

WordsKaty Grannan: Central Valley

Spring 2017 By Sarah M. Miller