FEMME FATALE ZOE CROSHER'S RECONSIDERED ARCHIVE OF Michelle du Bois

ARCHIVE

JAN TUMLIR

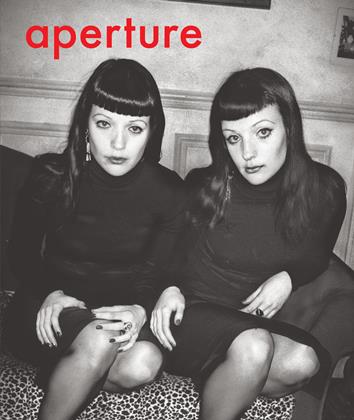

Over the course of a number of years, the artist Zoe Crosher acquired the entire pictorial output of an amateur photographer by the name of Michelle duBois. On the question of provenance, little else is revealed than this: the archive was given from one woman to another, duBois having adopted Crosher as a “spiritual mother.” That the two of them happen to have a faint physical resemblance suggests that there is more to this tale than meets the eye, as always.

Overall, duBois’s archive might be categorized as an exercise in variegated self-portraiture, but of a pointedly fragmented, deflected sort. For the most part produced in the 1970s and ’80s, the collection is pervaded with a host of psychological and geopolitical ambiguities. DuBois, an American woman, appears against one exotic backdrop after another—in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and so on—as a chameleonlike figure, continuously changing her stripes to blend in with the scenery. The “orientalist” swath that she cuts through the world in an era of Pax Americana is certainly idiosyncratic, and yet still closely aligned with that of her nation of origin. Restlessly shuttling from station to station, duBois describes the trajectory of a defiantly victorious United States, no longer isolationist, determined to spend its political capital as lavishly as possible. On both the personal and political levels, it quickly becomes clear that this is a document of misadventure.

Of particular interest to an art audience (though this is surely not the audience for which these decidedly intimate pictures were intended) is the way that the protean duBois can be seen as a Cindy Sherman avant la lettre. Although she is obviously not invested in any of the philosophical rationales that we have come to associate with the “Pictures Generation"—her contemporaries—this does not mean that we cannot read her project through that era’s poststructuralist lens. Critical theory comes with the territory that these pictures now occupy: the general context of art as well as the specific context that Crosher provides.

This point was made with the very first grouping of this material, 2005’s The Cindy Shermanesque (But She’s the Real Thing). Here, Crosher operates as a Duchampian curator, selecting only those shots that are most evidently art-like, those that appear to anticipate Sherman’s work. DuBois does not demonstrate the requisite distance from her subject—that is, herself—that would qualify her as a “true” feminist; this makes her particularly compelling to Crosher, and now to us. This work is not about the masquerade so much as it is of it. Moreover, if doubts are raised through the coupling, or twinning, of these two women with cameras, those doubts cut both ways. Whose deconstruction of identity is more intentional? The question itself is absurd.

Here it is worth recalling Douglas Huebler’s axiom of 1969: “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” Huebler conflated the photograph and the readymade, and indeed, it was as a means of dematerialization that the camera was so enthusiastically seized by Conceptual art’s post-studio crowd. For the generations that followed, however, the camera’s products would grow to be more and more thick and resistant. In the hands of a Sherman, a Louise Lawler, a Richard Prince, the print becomes a “thingly” thing (as Heidegger would say). Similarly, in her subsequent reconfigurations of the archive (the project, which began in 2005, is ongoing), Crosher began attending to the materiality of duBois’s photographs, though now specifically as artifacts of an analogue age. From identity politics to an examination of a medium in the midst of transition, the artist’s incursions into this found collection increasingly highlight the way that technologies “speak” via their human operators, and how their messages change over time. Accordingly, even duBois’s fetishism for all things Asian comes to seem almost pre-programmed—or instamatic. The stiffly abstract formalism of her poses, the undisguised artifice of her expressions, all of it is Kodak-inspired Kabuki.

This loop of self-presentation and self-scrutiny is never broken. Even the banal itemized documentation of duBois’s collection of Geisha dolls (her other Big Subject) is drawn into its vortex. On the flyer for a recent exhibition, Crosher reproduces a note scrawled by duBois on the back of a photograph: “Beautifully painted and powdered Geisha neck, very important part of makeup.” This “peek behind the scenes” reveals a verso no less false than the recto, and no less true.

From the outset, we sense that something is off: even before duBois takes to signing her prints in the names of her various alter egos—Alice, Kathy, Mitchi, etc.—we have begun to suspect the authenticity of the original. However, like Blanche DuBois, the character-playing-a-character in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Michelle duBois lies tellingly. When Crosher is added to the mix, this riddle of identity is compounded. Who is really in control? Is this a tale of army-base prostitution and/or Mata Hari-style espionage? The answer is beside the point; it is only the question that counts here, as framed by a medium that could be decomposing before our eyes. It is as though the artist were simply halting the process for one last look, while there still remains something for us to see. Just before subject and object are fused in rotten flatness, Michelle duBois bends down to show off her cleavage. In the same way she has done countless times before, she arches her back and stares straight ahead, both playmate and sphinx.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Witness

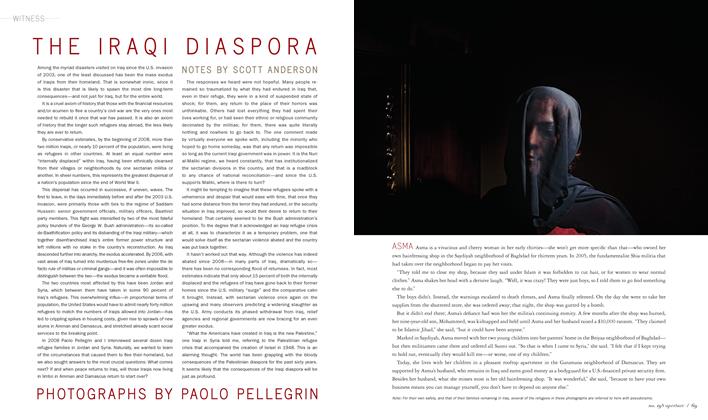

WitnessThe Iraqi Diaspora

Spring 2010 By Scott Anderson, Paolo Pellegrin -

Work And Process

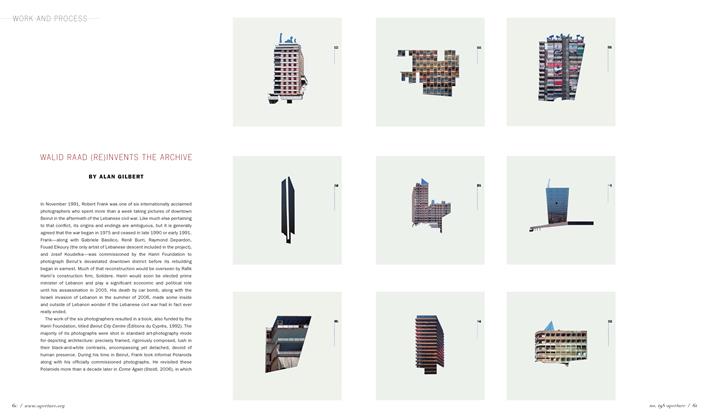

Work And ProcessWalid Raad (re)invents The Archive

Spring 2010 By Alan Gilbert -

Dialogue

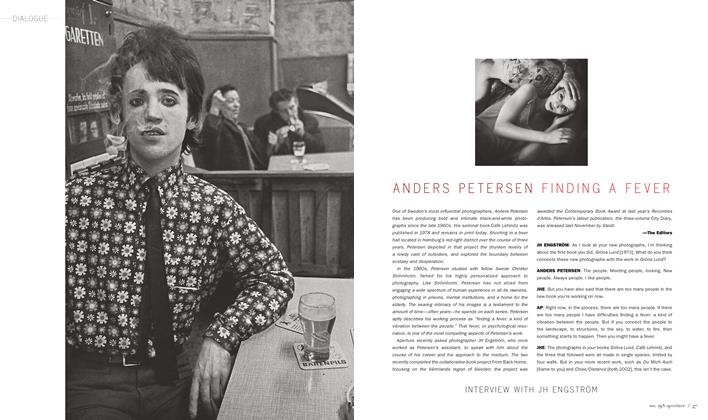

DialogueAnders Petersen Finding A Fever

Spring 2010 By The Editors, Jh Engström -

Close Encounters

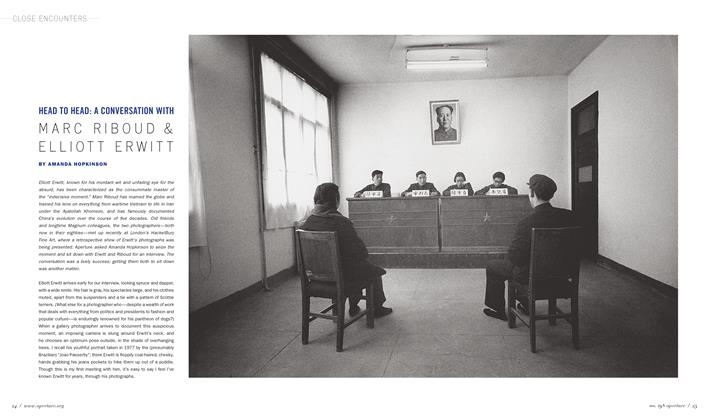

Close EncountersHead To Head: A Conversation With Marc Riboud & Elliott Erwitt

Spring 2010 By Amanda Hopkinson -

Artist's Project

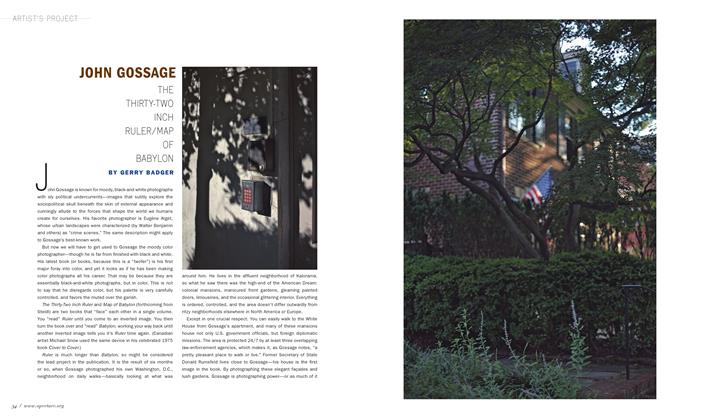

Artist's ProjectJohn Gossage

Spring 2010 By Gerry Badger -

On Location

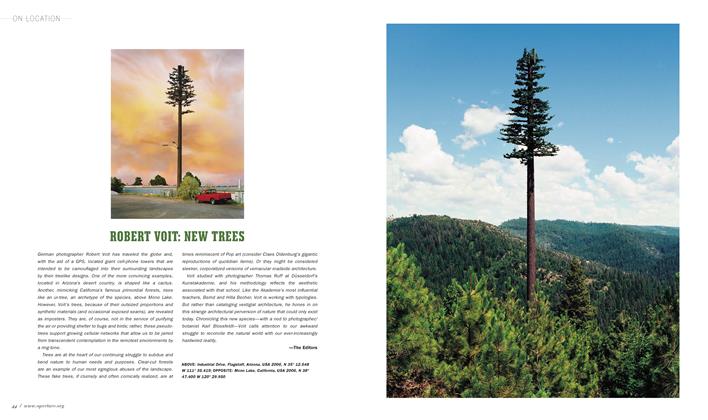

On LocationRobert Voit: New Trees

Spring 2010 By The Editors

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jan Tumlir

Archive

-

Archive

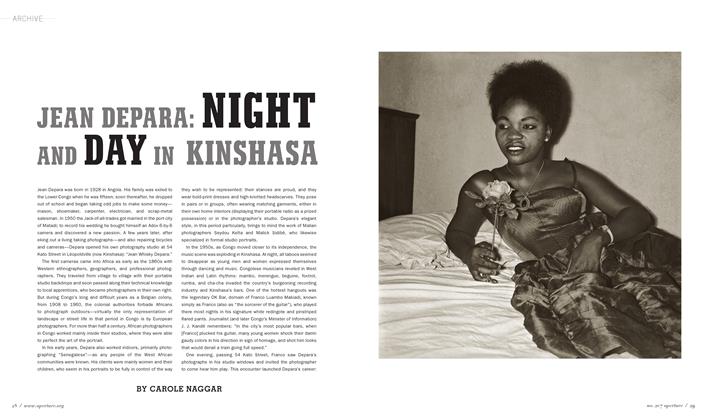

ArchiveJean Depara: Night And Day In Kinshasa

Summer 2012 By Carole Naggar -

Archive

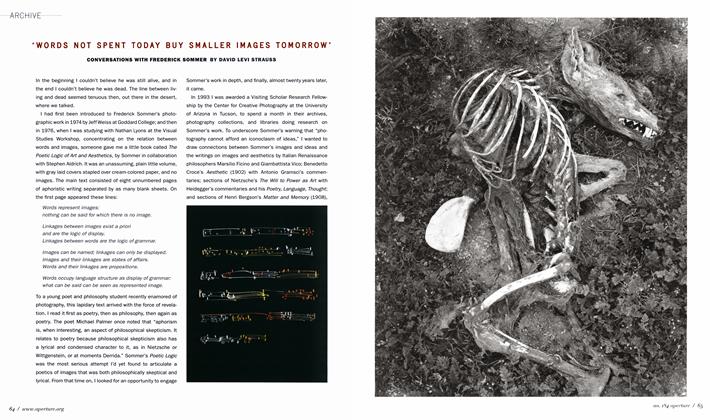

Archive"Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow"

Fall 2006 By David Levi Strauss -

Archive

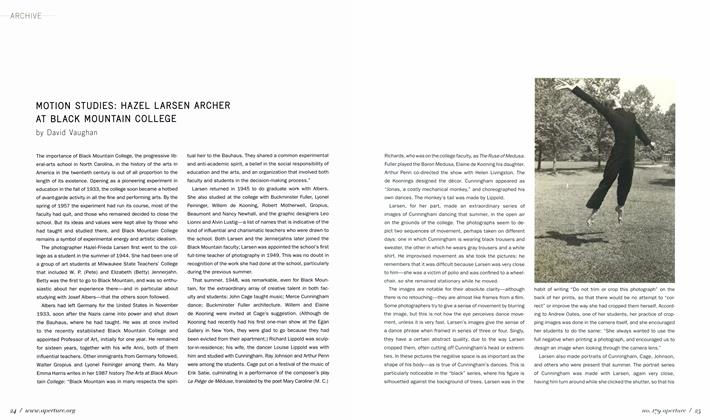

ArchiveMotion Studies: Hazel Larsen Archer At Black Mountain College

Summer 2005 By David Vaughan -

Archive

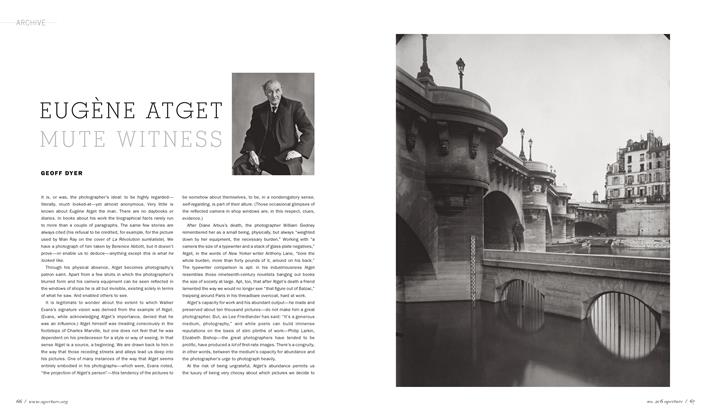

ArchiveEugène Atget Mute Witness

Spring 2012 By Geoff Dyer -

Archive

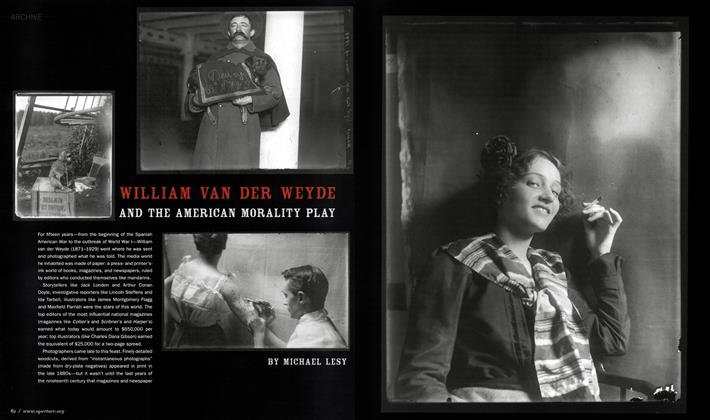

ArchiveWilliam Van Der Weyde And The American Morality Play

Spring 2009 By Michael Lesy -

Archive

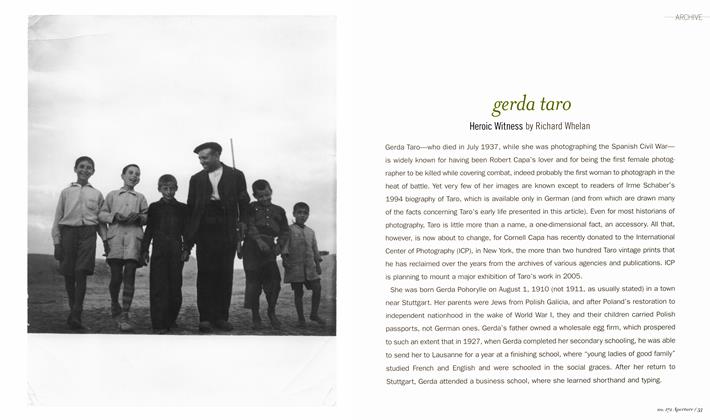

ArchiveGerda Taro

Fall 2003 By Richard Whelan