COLLIER SCHORR BOTH SIDES NOW

PORTFOLIO

Vince Aletti

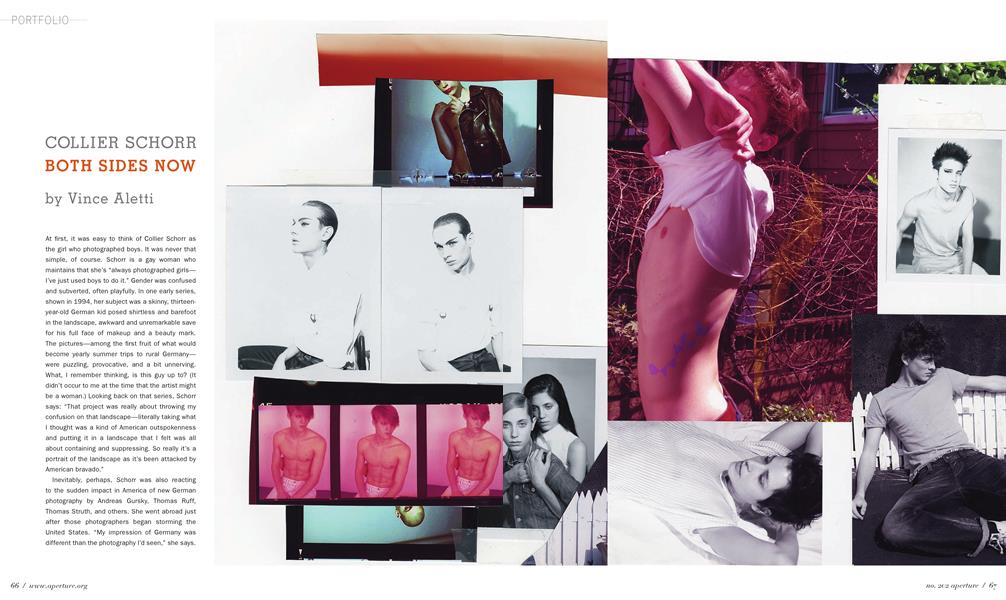

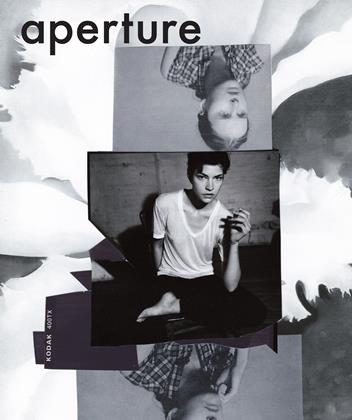

At first, it was easy to think of Collier Schorr as the girl who photographed boys. It was never that simple, of course. Schorr is a gay woman who maintains that she's "always photographed girls— I've just used boys to do it." Gender was confused and subverted, often playfully. In one early series, shown in 1994, her subject was a skinny, thirteenyear-old German kid posed shirtless and barefoot in the landscape, awkward and unremarkable save for his full face of makeup and a beauty mark. The pictures—among the first fruit of what would become yearly summer trips to rural Germany— were puzzling, provocative, and a bit unnerving. What, I remember thinking, is this guy up to? (It didn’t occur to me at the time that the artist might be a woman.) Looking back on that series, Schorr says: “That project was really about throwing my confusion on that landscape—literally taking what I thought was a kind of American outspokenness and putting it in a landscape that I felt was all about containing and suppressing. So really it’s a portrait of the landscape as it’s been attacked by American bravado.”

Inevitably, perhaps, Schorr was also reacting to the sudden impact in America of new German photography by Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, and others. She went abroad just after those photographers began storming the United States. “My impression of Germany was different than the photography I’d seen,” she says. “Either the country wasn’t the way I saw it in those pictures, or I was seeing something in the country that they didn’t see. And I think that what I was seeing was all the ghosts that they were ignoring.” As an American Jew, she says, “it’s a strange thing to go someplace where you are historically a victim but culturally the occupier,” but she felt emboldened to delve into images and issues the Germans preferred to avoid. If the Düsseldorf crew were going to remake every sort of August Sander photograph except the military ones, she would take that on. The results—photographs of teenagers lounging about in bits of Nazi uniforms ordered from a theatrical costume shop along with U.S. Army gear and sports camouflage—are audacious not just because they refuse an easy reading but because they are unapologetically beautiful. Photographing these boys playing dress-up, Schorr isn’t angry or horrified; she’s curious and unexpectedly affectionate. Writing about the series, she notes: “These pictures are as much about what I see in Germany as what I imagine I see, either through the veil of fantasy or an inherited anxiety. ... In a sense, perhaps the pictures were an attempt to flush history out into the open.”

Later, over a period of six years, Schorr burrowed into another sort of history for her 2005 book Jens F. (SteidIMack), an extraordinary project that involved photography, drawing, writing, and collage. What began as a photographic interpretation of Andrew Wyeth’s controversial drawings and paintings of his neighbor Helga Testorf—an extensive series of nudes and other intimate studies done unbeknownst to Wyeth’s wife and Helga’s husband— developed into Schorr’s most inspired and sustained riff on gender in flux. Jens, a German adolescent with a soft, fleshy body, stands in for Helga, pose for languid pose, but never totally naked. In the course of the project, there were other Helgas and models in supporting roles, including Jens’s younger sister, another boy, and a woman, whose presence was a breakthrough of sorts for Schorr. Finding her place in the New York art world, she’d learned early on that “there was no way to photograph a woman that wasn’t compromising on some level;” men, on the other hand, were “open season, and one could do with them what you wanted.” But when she found a woman who resembled Helga and who was willing to pose in the nude, she seized the opportunity. “What if the whole thing is just an attempt to learn how to photograph women?” she asks in a scrawl on one of the book’s early pages. But it was more than that: photographing a woman, she says, was about “coming to terms with my own fears of femininity and attraction to it and a real hunger.” She describes the process as “freeing,” and it added another layer to an already rich and complex project.

The format of Jens F. represented another breakthrough for Schorr. Using the pages of a second-hand copy of Wyeth’s published book The Helga Pictures as a combination scrapbook and sketchpad, she accumulated color and black-and-white photographs, drawings, and scraps of handwritten text. “This was never supposed to be a book,” Schorr says, but what began as a casual way of keeping track of which Wyeth images she had covered and which ones still needed to be done became the template for the finished product. At once slapdash and elegant, the collages in Jens F. are Schorr at her wittiest and most engaging. “It’s just one big conversation with myself,” she says, but it also provides a wide-open window onto her process. Since then, collage has shaped more and more of her work, but she doesn’t take it lightly. “For me,” Schorr says, “cutting into things is a literal transcription of a kind of criticism, particularly when it comes to the female form. I can’t do it just as an aesthetic exercise because it means too much. Jens F. was a conversation and competition with Wyeth—mimicking his gaze to arrive at a representation of femininity woven between the action of posing a figure and the figure itself. Coilaging became a really aggressive tactic—like a giant land grab—as well as a second way of being engaged. First is through the camera; the collage is like a secondary text. It’s not aesthetically based; it’s so I can tell something, not so I can show something. It allows me to talk about the subject from several different points of view—to make a photo that has something before and after, like it does in the making of a picture.”

Collage has also become an important element in the fashion photography—both editorial and advertising—that Schorr has done over the past five years. Working first with male models and now with both men and women, she’s become known for an understated style that’s more about intimacy and idiosyncrasy than polish. A shoot for the June 2010 issue of the British style magazine Dazed & Confused, full of cut-up images, was especially dense and brilliant—and probably would not have happened without the precedent of Jens F. “Fashion photography is what first drew me into photography,” Schorr says. “Music was never as much of an escape as fashion magazines. Being an artist can be an isolating experience. I liked the idea of something more collaborative and temporary, and that you could have an impact on people outside your little world. I love photography so much that it seems to make sense to try a lot of things. It’s fun and it’s sexy, and I had the opportunity to take away pictures for myself.” Fashion work has also enabled Schorr to put to rest the idea that she only photographs boys, and that is another liberation for her. “There’s something about shooting a model,” she says, “where I no longer see it as a female or male body; I see it as a fashion body. There’s a freedom when you shoot somebody in a fashion shoot because it’s all agreed to. They go into it with an understanding that they’re about to be consumed. I know fashion is also a way to consume, to adore, to objectify a female body. I’m still completely conflicted about it, but now I’m allowing myself to just acknowledge the gaze as a vulnerable mode of description, the way the artist is consumed by the privilege of description.”©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

On Location

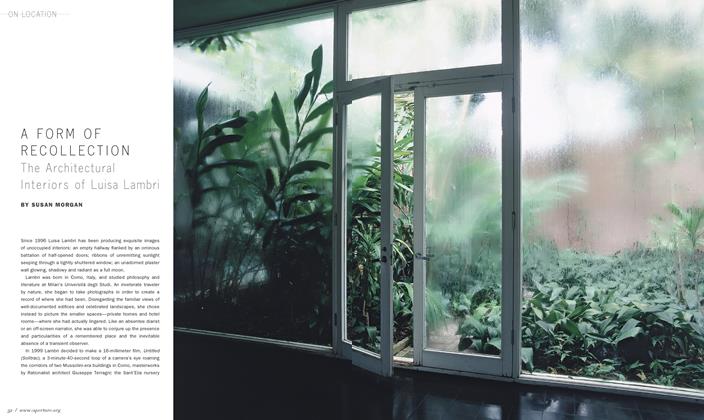

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

Essay

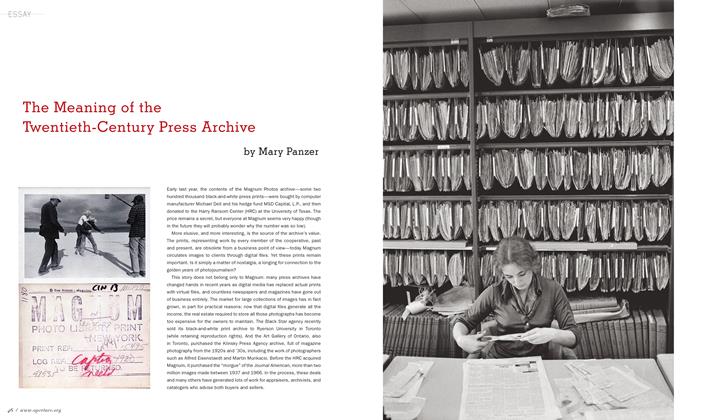

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Archive

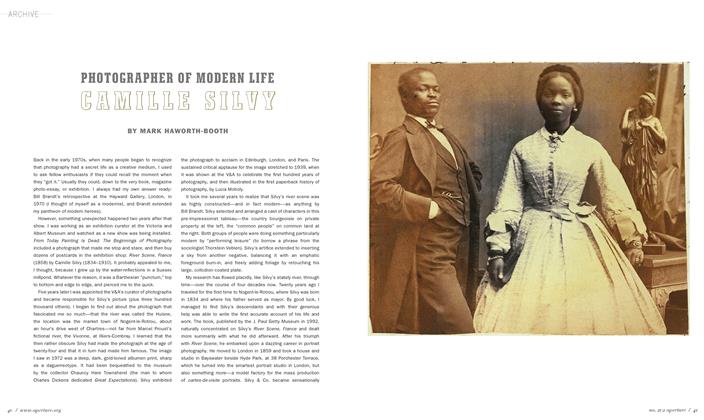

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Vince Aletti

-

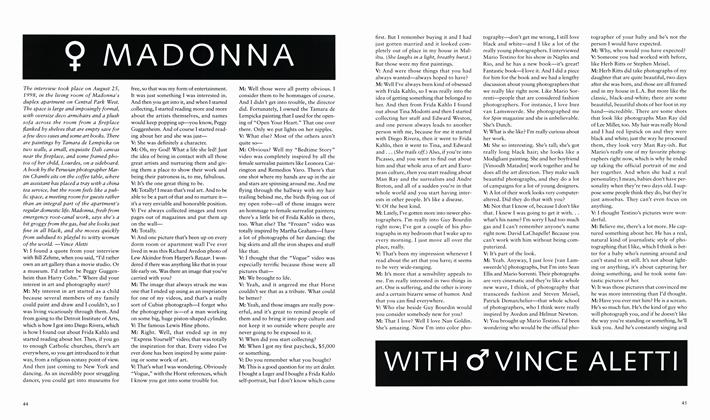

♀ Madonna With ♂ Vince Aletti

Summer 1999 By Vince Aletti -

Reviews

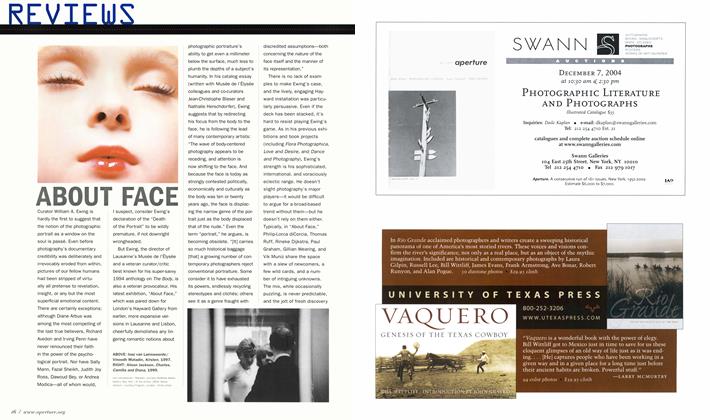

ReviewsAbout Face

Winter 2004 By Vince Aletti -

Mixing The Media

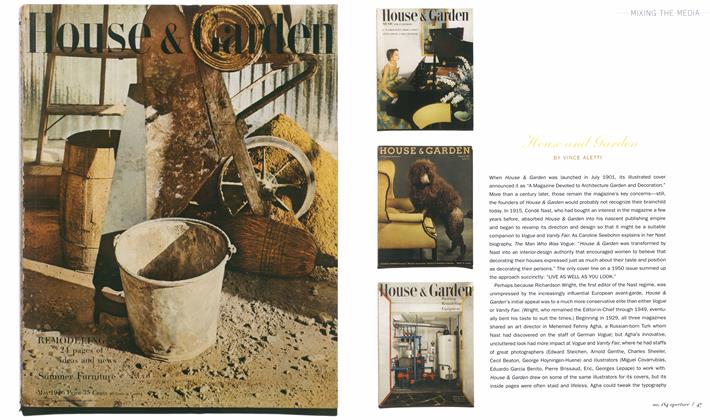

Mixing The MediaHouse And Garden

Fall 2006 By Vince Aletti -

Redux

ReduxIn Our Terribleness

Winter 2013 By Vince Aletti -

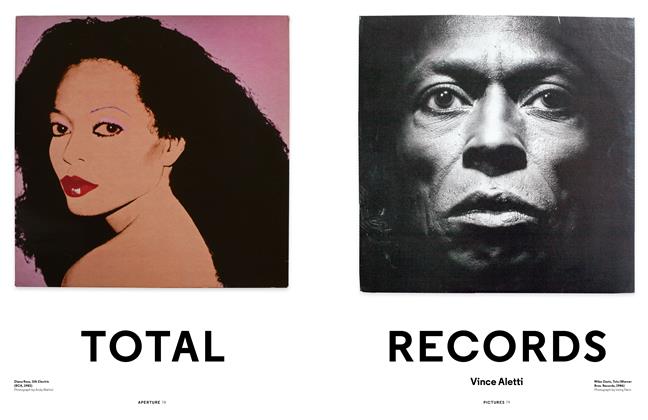

Pictures

PicturesTotal Records

Fall 2016 By Vince Aletti -

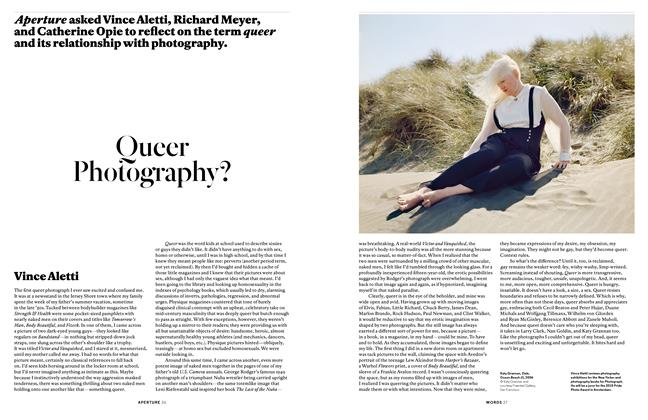

Words

WordsQueer Photography?

Spring 2015 By Vince Aletti, Richard Meyer, Catherine Opie

Portfolio

-

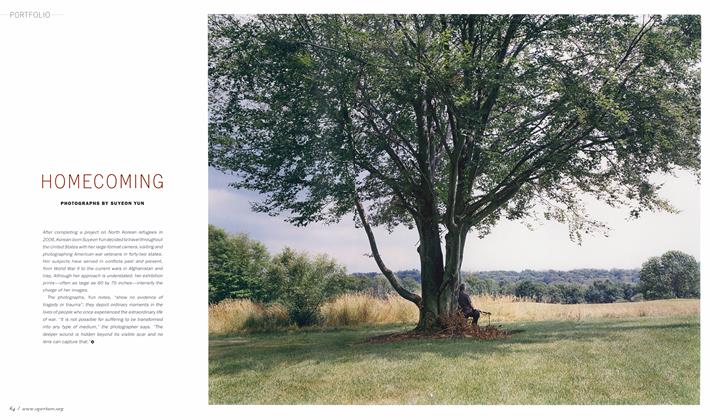

Portfolio

PortfolioHomecoming

Summer 2009 -

Portfolio

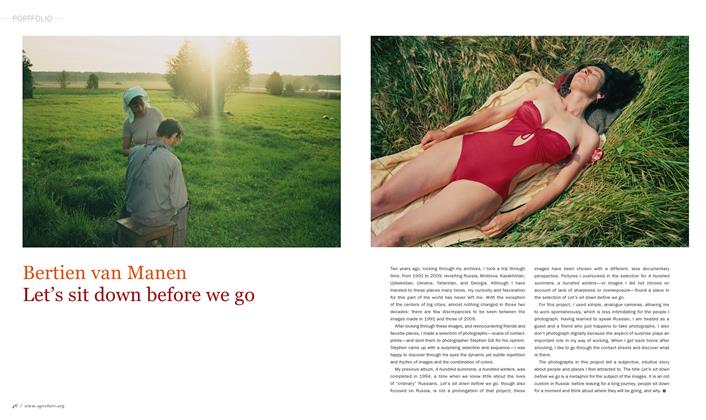

PortfolioBertien Van Manen Let's Sit Down Before We Go

Fall 2012 By Bertien Van Manen -

Portfolio

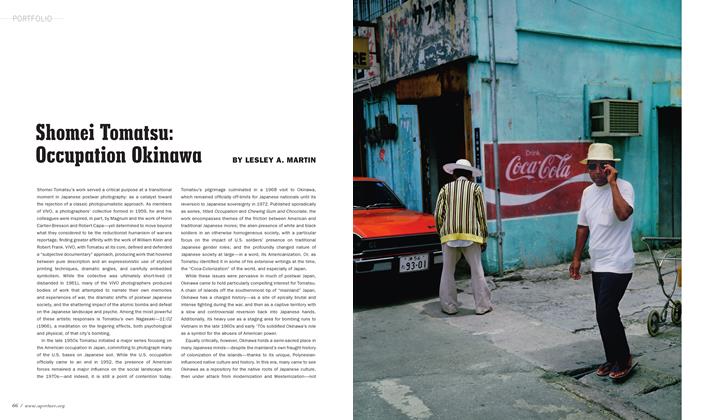

PortfolioShomei Tomatsu

Fall 2012 By Lesley A. Martin -

Portfolio

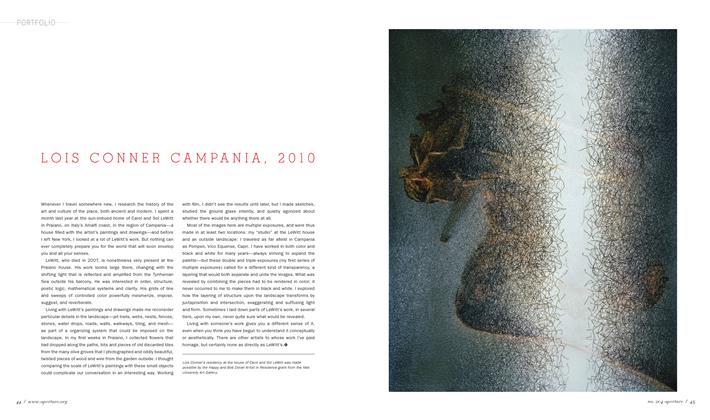

PortfolioLois Conner: Campania, 2010

Fall 2011 By Lois Conner -

Portfolio

PortfolioLieko Shiga Out Of A Crevasse: The Days After The Tsunami

Spring 2012 By Mariko Takeuchi -

Portfolio

PortfolioColour Before Color

Spring 2008 By Martin Parr