Where We’ve Come From: Aspects of Postwar British Photography

Mark Haworth-Booth

Sexual intercourse began In nineteen sixty-three (Which was rather late for me)—

Between the end of the Chatterley ban And the Beatles’ first LP.

This is the opening stanza of “Annus Mirabilis,” by Philip Larkin, who constitutes almost a one-man tradition in postwar English poetry. His lines make fun of arbitrary retrospective chronologies and questions like “When did contemporary British photography begin?” However, it is worth asking the question in order to raise another one: is there an identifiable tradition behind photography in Britain now? A striking difference between expressive photography in the United States and Britain, or for that matter any other country, is that in the U.S. a canon of photographic art has been articulated in a comprehensible form. Perhaps the same is true of jazz. The efforts of such individuals as Alfred Stieglitz, Beaumont Newhall, and Edward Steichen, and of a number of important institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and George Eastman House in Rochester, have given American photography a degree of self-awareness, a sense of continuity and direction, that for the most part has been lacking in Britain and elsewhere. However, in the last fifteen or twenty years photographers in Britain have made good the omissions of their native institutions by adopting a large part of the American tradition as their own.

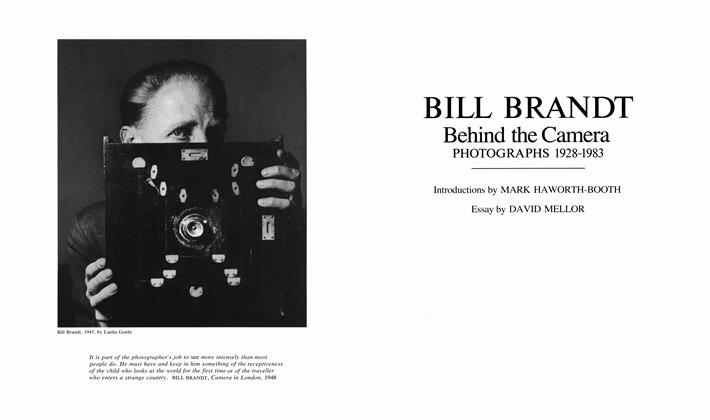

For some, contemporary photography began in 1970 at the Hayward Gallery on London’s South Bank. The exhibition rooms were painted black, the photographs were by Bill Brandt—and they had been selected by John Szarkowski, Director of the Department of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where the exhibit had originated the previous year. The catalogue essay was by the one art historian in Britain who concerned himself seriously with the medium of photography, Professor Aaron Scharf—an expatriate from California. Scharf closed his essay with a warning and a witticism: “We have become used to treating photographs as pictorial ephemera, and at the connivance of photo-mechanical reproduction are in danger of treating all art that way. I once saw a lady, an intelligent-looking and presentable lady, rushing up the great inner staircase of the Louvre, shouting with a frantic note in her voice, ‘Guard! Quick! The Mona Lisa! Where is she? I’m double-parked!’ Don’t go to Brandt in that way. The longer you look, the more you’ll find and so much richer will be your experience.”1 After its London showing the exhibition was toured by the Arts Council of Great Britain to twelve other U.K. venues, and was received with acclaim. The exhibition prepared a new audience, as well as a new generation of critics, for the great enlargement of photographic activity that followed in the 1970s.

It was perhaps inevitable that such an important exhibition would have featured Brandt’s work. As Larkin had in poetry, Brandt constituted almost a one-man tradition in British photography. Is there a British photographer who has not learned from him? Any reservations photographers have about Brandt’s print style or quality or, for some, the wide-angle distortions of his nudes, always seem peripheral matters. Brandt’s reticence made it easier for him to be admired creatively—he invited imaginative esteem. His life, like his work, left a great deal to the imagination.2 Although he loved working on commissions he was to become a model for the independent photographers of the 1970s and ’80s. Through his work, shown and collected by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from 1948 on, and by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from 1965 on, Brandt not only demonstrated the creative possibilities of the photographic medium when allied with imagination and intellect, but also provided an image of integrity.

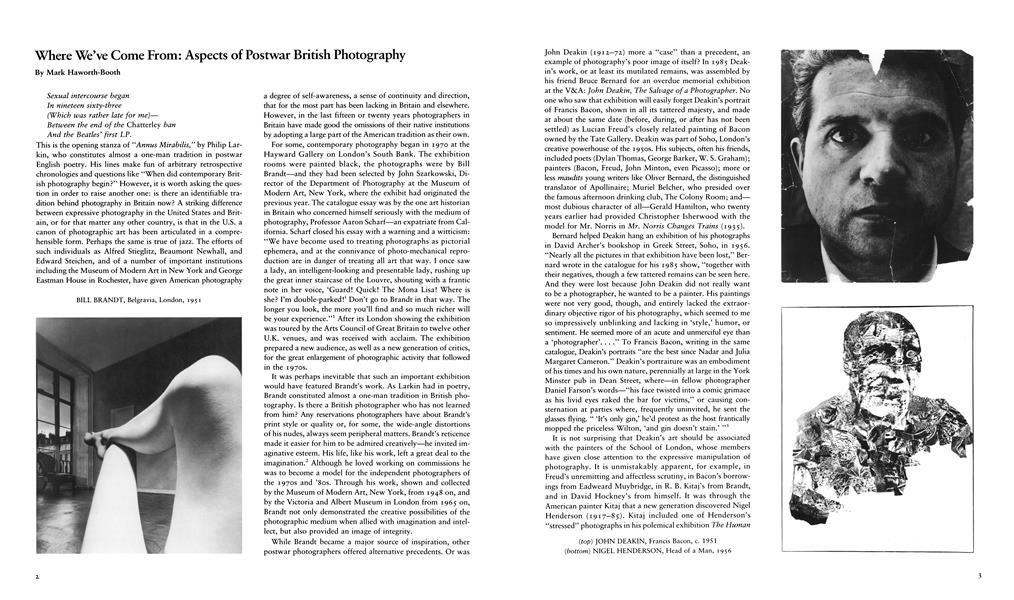

While Brandt became a major source of inspiration, other postwar photographers offered alternative precedents. Or was John Deakin (1912—72) more a “case” than a precedent, an example of photography’s poor image of itself? In 1985 Deakin’s work, or at least its mutilated remains, was assembled by his friend Bruce Bernard for an overdue memorial exhibition at the V&A: John Deakin, The Salvage of a Photographer. No one who saw that exhibition will easily forget Deakin’s portrait of Francis Bacon, shown in all its tattered majesty, and made at about the same date (before, during, or after has not been settled) as Lucian Freud’s closely related painting of Bacon owned by the Tate Gallery. Deakin was part of Soho, London’s creative powerhouse of the 1950s. His subjects, often his friends, included poets (Dylan Thomas, George Barker, W. S. Graham); painters (Bacon, Freud, John Minton, even Picasso); more or less maudits young writers like Oliver Bernard, the distinguished translator of Apollinaire; Muriel Belcher, who presided over the famous afternoon drinking club, The Colony Room; and— most dubious character of all—Gerald Hamilton, who twenty years earlier had provided Christopher Isherwood with the model for Mr. Norris in Mr. Norris Changes Trains (1935).

Bernard helped Deakin hang an exhibition of his photographs in David Archer’s bookshop in Greek Street, Soho, in 1956. “Nearly all the pictures in that exhibition have been lost,” Bernard wrote in the catalogue for his 1985 show, “together with their negatives, though a few tattered remains can be seen here. And they were lost because John Deakin did not really want to be a photographer, he wanted to be a painter. His paintings were not very good, though, and entirely lacked the extraordinary objective rigor of his photography, which seemed to me so impressively unblinking and lacking in ‘style,’ humor, or sentiment. He seemed more of an acute and unmerciful eye than a ‘photographer’. . . .” To Francis Bacon, writing in the same catalogue, Deakin’s portraits “are the best since Nadar and Julia Margaret Cameron.” Deakin’s portraiture was an embodiment of his times and his own nature, perennially at large in the York Minster pub in Dean Street, where—in fellow photographer Daniel Farson’s words—“his face twisted into a comic grimace as his livid eyes raked the bar for victims,” or causing consternation at parties where, frequently uninvited, he sent the glasses flying. “ ‘It’s only gin,’ he’d protest as the host frantically mopped the priceless Wilton, ‘and gin doesn’t stain.’ ”3

It is not surprising that Deakin’s art should be associated with the painters of the School of London, whose members have given close attention to the expressive manipulation of photography. It is unmistakably apparent, for example, in Freud’s unremitting and affectless scrutiny, in Bacon’s borrowings from Eadweard Muybridge, in R. B. Kitaj’s from Brandt, and in David Hockney’s from himself. It was through the American painter Kitaj that a new generation discovered Nigel Henderson (1917-85). Kitaj included one of Henderson’s “stressed” photographs in his polemical exhibition The Human Clay, shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1976. This exhibition and catalogue, with its title from W. H. Auden, was Kitaj’s declaration of faith in figuration. The Henderson piece, now in the collection of the Arts Council of Great Britain, weirdly and wonderfully stretched a human figure into the likeness of a column. However, perhaps the most potent photographic image of the English 1950s is Henderson’s “Head of a Man” (1956) in the Tate Gallery. This impressive photographic collage was made for the “Patio and Pavilion” section of the exhibition This is Tomorrow, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1956.4 With this show, made up of twelve installations, popular culture decisively became an important subject of fine art. “Head of a Man,” matted with bits of media junk thrown together into one existential whole, summarized the Britain of postwar austerity and its aftermath. Perhaps the piece owes much to Henderson’s wartime experiences flying R.A.F. bombers—experienees from which it took him years to recover—and something to his jobs teaching photography when there was virtually nothing by way of equipment with which to teach or practice, other than the cobbled together and randomly improvised. Most of all, though, the work testifies to his appetite for despised, demotic imagery. His masterwork, “Head of a Man” offered a looming new perspective: man as the intersection of a complex of technologies, including picture systems.

It was in 1956, too, that Roger Mayne (born in 1929), who admired Henderson’s street photographs and would himself be photographed by Deakin, found the territory he made his own: London’s North Kensington area, notably Southam Street, the same district in which Colin Maclnnes set his epoch-making novel Absolute Beginners (1959). Mayne photographed this particular street regularly for five years. His imagery suggests a reaching out for new forms of solidarity between social classes in the early years of Britain’s new welfare state and “Butskellite” (a word, based on the names of R. A. Butler and Hugh Gaitskell, that has been coined to indicate a common Labor and Conservative middle ground) consensus. Mayne’s most famous picture from this period, of a screaming girl running toward the photographer, was taken in Southam Street on one of his first visits and was included in his first important exhibition, held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1956. Interestingly, the show was reviewed in the Times (July 13, 1956) by Colin Maclnnes, who wrote of Mayne and Deakin together:

What strikes one most, indeed, about the work of both of these artists—at a time when photography is so often concerned with spurious glamour and the “picturesque”—is their scrupulous regard for truth. And if an artist be one who, by the pictorial illusion he creates, can heighten the spectator’s sense of the reality of the visible world, then both Mr. Deakin and Mr. Mayne may lay unquestionable claim to being artists of high quality.

Mayne was a partisan of Cartier-Bresson’s aesthetic and was in contact with Paul Strand in Paris as well as Minor White in Rochester. With the older photographer Hugo van Wadenoyen, Mayne organized international exhibitions which included work from continental Europe and the U.S. as well as from Britain. These exhibitions were organized by the “Combined Societies,” an amalgamation of photographic clubs and societies, and were mainly shown in provincial art galleries—but also, once, at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1953—54; in addition, the last of the series (1955—57) toured to George Eastman House and San Francisco State College in the United States. At the time Mayne wrote to the then Director of the V&A, Sir Leigh Ashton, to ask whether the museum would show the exhibitions or collect contemporary photography. Ashton’s answer was crisp. Photography, he wrote back, was “a mechanical process into which the artist does not enter” (letter dated December 8, 1954).5

Mayne’s work met with a more sympathetic response at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where Steichen bought some examples in 1956. For many years Mayne was the only contemporary British photographer, apart from Brandt, shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent exhibition. From the mid 1960s on his work was also collected and circulated by the V&A, and in 1977—to mark the moment when the V&A became responsible, in the system of national museums in Britain, for the collection, preservation, and study of the art of photography—Mayne gave the Museum his “Southam Street Album.”

Despite Mayne’s pioneering role, British street photography of the 1970s and ’80s took its cue not from him but from the brief incandescence of Tony Ray-Jones (1941—72). The mordant choreography of his imagery exercised a compelling influence on the early work of Chris Steele-Perkins, now best known for his international reporting with Magnum, and in the 1980s has been adapted to the task of describing British consumerism by Martin Parr and younger photographers who have in turn been influenced by Parr. A ferocious wit is also to be found in the work of the Picture Post veteran G. Thurston Hopkins, born in 1913. After the magazine shut down in 1957 Hopkins moved into advertising, then teaching.

Teaching also harbored the talent of Raymond Moore (1920— 1987), who trained as a painter at the Royal College of Art. Inspired by Otto Steinert’s Subjektive Fotografie books (1952 and 1955) Moore began to photograph seriously in 1956, finding his initial subjects on the beaches of the Pembrokeshire coast and the island of Skomer. His work developed into an intricate, understated art that seems particularly English in its simultaneous exploration of the photographic gray scale and the nuances of a predominantly northern (gray) climate, producing images that are at once down to earth, steeped in melancholy, and broken with serendipitous illuminations. He found a friend and a fine exponent in the American poet Jonathan Williams, who wrote in The Independent (October 7, 1987) after Moore’s untimely death:

I have met no one in England with that beady eye of his. Very much the somber, ancient albatross, with his sea-captain’s beak and his (always) black sweater. Tie loved the act of seeing. His photographs are filled with extraordinary little touches and visual nuances. There is the one of the house called Allonby, 1982, perhaps the ugliest house one has ever seen, yet full of magical detail: white wires, black wires, little bits of black this-and-that popping up here and there, illusive reflections, grasses, odd shadows indeed. What a relief his pictures are in a claustrophobic, bland country.

When Don McCullin went the rounds of newspaper offices in London at the end of the 1950s with his pictures of teenagers, he found that his work was constantly compared to Mayne’s. From the time of his reports on the civil war in Cyprus in 1964, though, McCullin’s photography became recognizably his own. A generation became acquainted with the world’s disasters through McCullin’s photographs, usually as published in the pages of the Sunday Times Magazine. No doubt many people in Britain can remember exactly where they were when they saw McCullin’s photographs from Hue (Sunday Times Magazine, March 24, 1968; see also the New York Times, February 28, 1968). In 1983, however, when Britain conducted its own hostilities in the South Atlantic after the Argentinian invasion of the Falkland Islands, McCullin was barred from photographing the conflict by the Ministry of Defence. Later the Sunday Times was acquired by Rupert Murdoch, and became a different kind of newspaper. In an interview with Granta (Winter, 1984), McCullin unburdened himself: “I still work for the Sunday Times, but they don’t use me. I stand around in the office, and don’t know why I’m there. The paper has completely changed: it’s not a newspaper, it’s a consumer magazine, really no different from a mail-order catalogue. And what do I do, model safari suits?”

Recently McCullin’s work, thinly disguised, took its place in fiction, appearing in Graham Swift’s novel Out of This World (1988). Perhaps fiction is a key word for what has occurred in photography in the past decade or two. Chris Killip, the most important realist photographer in Britain since McCullin, prefaces his book In Flagrante (1988) with the statement that “the book is a fiction about metaphor”—although it is clearly also about deindustrialization. I think Killip meant two things by his remark: first, that prevailing governmental views about contemporary society and its antecedents are no more than fictions, which must be opposed by other, more compelling, fictions; and secondly, that since the heyday of Brandt, Mayne, Deakin, and even McCullin, photography has, for better or worse, become an art medium. Its role in providing mass information has been altered, if not replaced, by TV. But by the same token its “role” has been seen to be precisely that—simply another method of establishing illusions.

The year 1970 was significant not only because of Bill Brandt’s retrospective; it was also the year of Richard Hamilton’s Tate Gallery retrospective. Hamilton’s work then and since has focused, as he put it in the catalogue for that exhibition, on the “transition between the painted image, the photographic image, . . . simulations of three-dimensional space, and the real thing.” Included in the 1970 show was a series of “Cosmetic Studies,” in which elements of fashion photography—details of the model Veruschka’s famous face, for example—were combined with such objects as a mirror in which the viewer’s own face ironically confronts the world of the fashion plate.

Working in a similarly ironic, analytical manner, Hamilton was later to adapt the sacrosanct conventions of late Cézanne to the project of advertising Andrex toilet paper, in a series of pseudo-“spirited” gouache paintings. John Berger’s writings and his BBC television series Ways of Seeing (1972) also provided liberating, penetrating discussions of the relationship between popular culture and photography. However, it is because of Hamilton’s challenging presence that the more profound concerns of Pop art have remained important for every subsequent generation of art students in Britain. He is as much a presiding genius of British photography today as is Brandt. In a 1984 installation, included in a new retrospective now touring Britain, Hamilton offers a biting commentary on the state of the nation. The postwar consensus is over and the welfare state under threat of dismantlement. Hamilton’s work, devised in “Orwell’s year,” presents a hospital bed with a TV monitor stationed in what would be the center of a prone patient’s field of vision. On the screen is Mrs. Thatcher delivering an election speech. The tape is soundless, and endlessly rerun. Hamilton’s installation can be seen as a direct response to what Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock recently referred to as Thatcher’s “psychological warfare against the National Health service,” but it reverberates with broader meanings as well.

Apart from Hamilton’s work, the arrival of photography as an avant-garde art medium in Britain can be dated to the key exhibition The New Art, selected by Anne Seymour of the Tate Gallery and shown at the Hayward Gallery in 1972. Exhibiting artists were Keith Arnatt, Art-Language, Victor Bürgin, Michael Craig-Martin, David Dye, Barry Flanagan, Hamish Fulton, Gilbert and George, John Hilliard, Keith Milow, Richard Long, Gerald Newman, John Stezaker, and David Tremlett. Among the media used by these artists were sound, video, and language, but photographs and text predominated. In 1984 Hannah Collins used a similar combination of media—sound, text, and found photographs—in her installation Evidence in the Streets: War Damage Volumes, shown at Interim Art, London. This work was based on photographs from local histories showing Second World War bomb damage to the Hackney, East London, area in which Collins lives. These reference photographs were enlarged to almost cinematic proportions, printed by the cyanotype process, and shown with an accompanying sound track. Where McCullin was prevented from getting anywhere near the Falklands, Collins was able to express at least some of the feelings aroused by the conflict by making use of local materials. By using cyanotype, she was also able to float historical records into the regions of memory—or prophecy—in the manner of certain moments in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, an artist of great importance to her. Other films are part of the essential background of contemporary British photography: Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsmans Contract (1982), for its use of the historical tableau; Richard Eyre’s The Ploughmans Lunch (screenplay by Ian McEwan, 1983), with its investigation of bad faith in the making of historical—and advertising—illusions; romantic realist films from regional cities, including Bill Forsyth’s Gregory’s Girl (1980), from Glasgow, and Chris Bernard’s A Letter to Brezhnev (1985), from Liverpool, which echo the documentary tradition revitalized by the Side Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne; and, finally, the sharp and witty presentation of the brutalisms and pluralisms of the new Britain of the 1980s, the Hanif Kureishi/Stephen Frears films My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and Sammy and Rosie Get Laid (1987).

Photography in Britain now draws on many diverse sources of inspiration. Despite this, the sense of a specifically photographic tradition has been only intermittent. (The full history of postwar photography in Britain is in fact far richer than can be indicated in this brief essay, and includes, for example, Brandt’s staunch ally Norman Hall, the editor of Photography magazine, and the subtle Edwin Smith, as well as women photographers of the stature of Grace Robinson, of Picture Post, and the portraitist Ida Kar.) However incomplete it may be, this survey may serve as a fruitful source of ideas and imagery for the new work of the 1990s—work that will both draw on and challenge the traditions that have preceded it.

1 Aaron Scharf, “The shadowy world of Bill Brandt,” introduction to Bill Brandt Photographs (London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1970). 2 The record of Brandt’s early career was sketched first in Literary Britain, as revised and published by the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1984 and reprinted in association with Aperture in 1986, and then far more fully in the Aperture monograph Bill Brandt: Behind the Camera, by David Melior and myself (New York: Aperture, Inc., 1985). 3 John Deakin; The Salvage of a Photographer, with texts by Bruce Bernard, Francis Bacon, Jeffrey Bernard, Daniel Farson, and Alexandra Noble (London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985). 4 Aspects of the exhibtion, including “Patio and Pavilion,” were reconstructed with what seemed touching fidelity at the Clocktower in New York in 1987, and the story of the exhibition was told and analyzed in This is Tomorrow Today: the Independent Group and British Pop Art (New York: The Institute for Art and Urban Resources, Inc., 1987). 5 The Street Photographs of Roger Mayne, p. 6 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986). The V&A has played a significant role in projecting the art of photography since 1968 when Henri Cartier-Bresson’s retrospective was shown, an event which changed the ethos for photography and museum-goers, and helped prepare the way for Brandt in 1970. 6 Richard Hamilton, introduction by Richard Morphet (London: Tate Gallery, 1970), p. 65.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Romances Of Decay, Elegies For The Future

Winter 1988 By David Mellor -

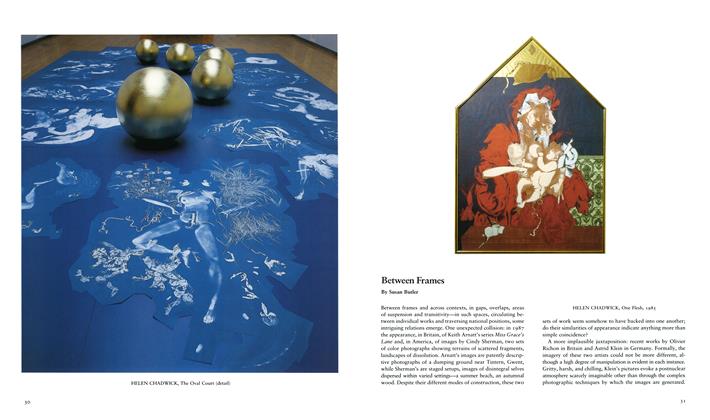

Between Frames

Winter 1988 By Susan Butler -

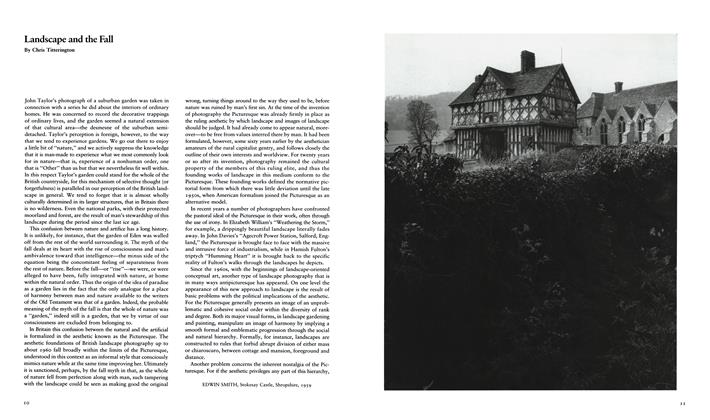

Landscape And The Fall

Winter 1988 By Chris Titterington -

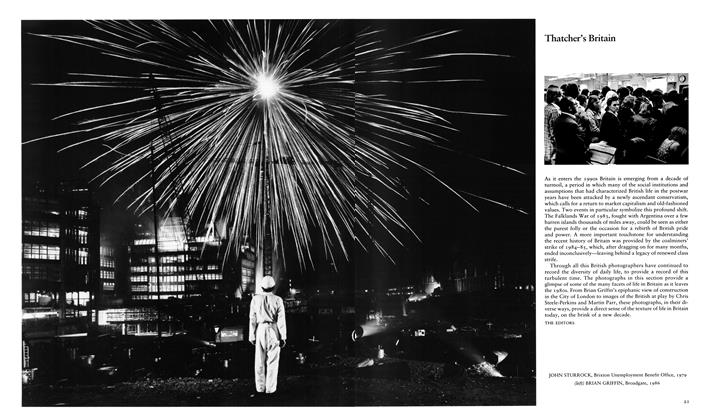

Thatcher’s Britain

Winter 1988 By The Editors -

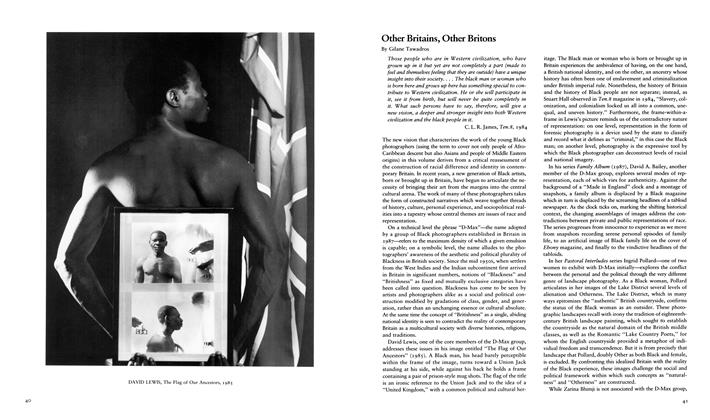

Other Britains, Other Britons

Winter 1988 By Gilane Tawadros -

Through The Looking Glass, Darkly

Winter 1988 By Rosetta Brooks

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mark Haworth-Booth

-

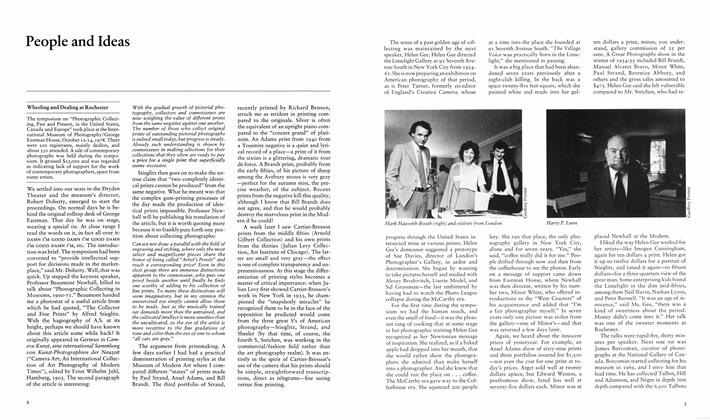

People And Ideas

People And IdeasWheeling And Dealing At Rochester

Winter 1979 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

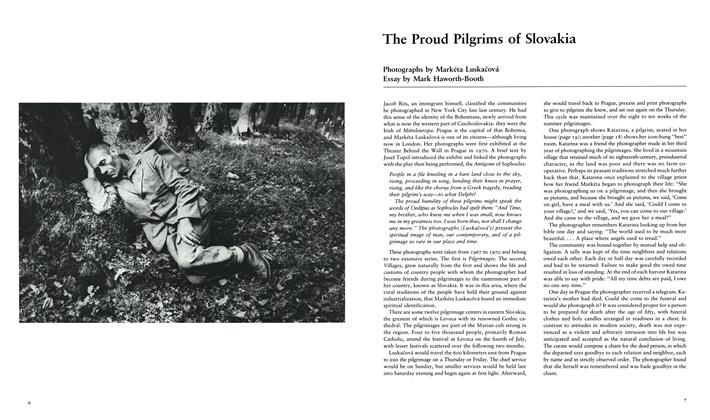

The Proud Pilgrims Of Slovakia

Fall 1983 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

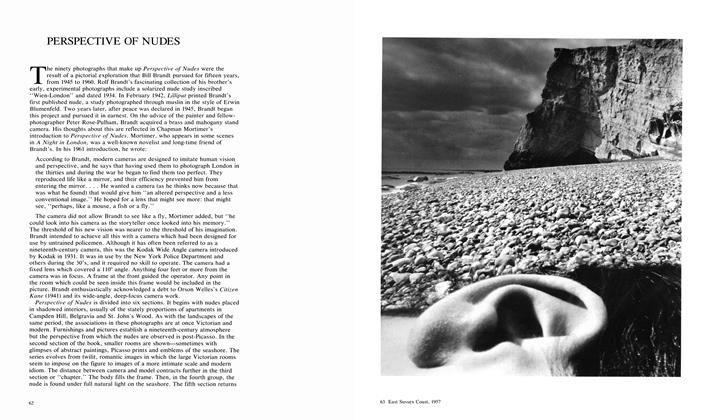

Perspective Of Nudes

Summer 1985 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Credits

Winter 2000 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Conferences

ConferencesConspiracy Dwellings

Fall 2008 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Bill Brandt Behind The Camera

Summer 1985 By Mark Haworth-Booth, David Mellor