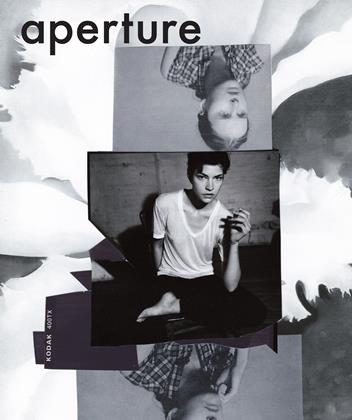

Sara VanDerBeek COMPOSITIONS

MIXING THE MEDIA

BRIAN SHOLIS

Sara VanDerBeek's contribution to the Museum of Modern Art's New Photography 2009 exhibition was A Composition for Detroit, a quartet of photographs made that year. Like the photographs she had been exhibiting for the previous half decade, it is made up of images of images: each panel depicts a geometric scaffold, erected against a dark backdrop in the artist's studio, to which she affixed reproductions of other photographs, including ones by Walker Evans and Leonard Freed. Unlike her earlier works, however, A Composition for Detroit also includes images VanDerBeek herself shot while visiting Motor City. Some of these component parts are in the background, obscured by the scaffolding or a painted pane of glass hung on it; others are depicted whole. VanDerBeek has said that the idea for the work came from a bank of broken windows she saw in Detroit, and the blank spaces in her composition—both within and between the four panels—deftly evoke that inspiration and give the work a syncopated rhythm. A Composition for Detroit is a threnody for a place laid low by the mid-century flight of manufacturing and its middle-class tax base, a place now grappling with the additional traumas of the current economic recession. With its inclusion of careworn photographic reproductions and its spacing across multiple panels, the work is also, more broadly, a meditation on time and entropy.

The photographs for which VanDerBeek first became known were, like the piece exhibited at MoMA, created in the studio with techniques borrowed from sculpture and collage. Most feature a single, somewhat rickety construction, laden with both photographic reproductions and talismanic objects—feathers, necklaces and chains, ribbons, and the like. The pictures are themselves invocations, calling forth the spirits of modernist precursors, from Constantin Brancusi and Alexander Calder to László Moholy-Nagy and Max Ernst; of classical cultures and historical figures; and of the artist’s father, the experimental filmmaker and artist Stan VanDerBeek, for whom the canny juxtaposition of images was second nature. Sara VanDerBeek brought together items ripped from the pages of art-history surveys and mass-market magazines or extracted from her father’s archive or from her own collections, placing them in exquisite if somewhat precious arrangements that she bathed in dramatic light. The resulting photographs, with evocative titles like A Different Kind of Idol, Ziggurat, and Mrs. Washington’s Bedroom (all 2006), are long on atmosphere and rich in allusions: each fragment is a keyhole into another world. Everything is suspended within shallow, anonymous spaces. These images, while possessing the qualities of a dream, are also commentaries on the erosion of boundaries in today’s media environment and on the instantaneous retrieval of historical information made possible by modern technology. They present history as image, or as a palimpsest of images. VanDerBeek makes calculated use of light, shadow, color, and the boundaries of the picture plane. Yet the prints are unusual in a distinct way. Each image is a one-to-one-scale replica of its subject: that is, a tabletop arrangement of twenty-by-sixteen inches results in a print of approximately the same dimensions. Each photograph is not only an index of something that once existed in the world; it is a direct copy of that worldly presence.

Having developed a unique pictorial language, VanDerBeek spent several years honing it, a process that first entailed the stripping away of extraneous elements and later the near total exclusion of photographic reproductions. The busily referential works she exhibited in 2006 gave way to a series of increasingly spare compositions, such as Eclipse I (2008). In that image, two photographic reproductions of ancient sculptural figures are affixed to a vertical, white-painted wooden pole. Also affixed to it is a thin metal ring from which emanates a series of string “rays” (likely the source of the work’s title). Subtle details animate the composition, reminding viewers that they are looking at a sculpture in space, not a flat image composed on a screen: one of the classical reproductions is affixed to the side of the pole and one to its front face; the entire arrangement is not perpendicular to the lens but slightly off-kilter; the “rays” slice diagonally downward, while the shadows the construction projects onto the white backdrop canter off in the opposite direction. After (2009) achieves a similar complexity without recourse to other images, relying instead on the play of angles and simple washes of paint over plaster and glass for incident.

In more recent works, color too has been drained from the image—VanDerBeek shoots with color film but prints in black and white. Caryatid (2010) is one example of this technique. A column of six cast-plaster forms rests on a sun-dappled wooden floor between two windows. The light streaming through them washes out the upper corners of the composition, leaving an inverted T to offset the thin vertical presence in the center of the image. Mirrors resting on the floor reflect VanDerBeek’s caryatid, hinting at Brancusian endlessness. Such a simple figure seems to aim for the impassiveness and iconicity of an architectural column or a totem pole, yet the handmade quality of VanDerBeek’s construction remains evident. Here is something stark and timeless, yet expressive of an individual maker.

VanDerBeek’s series of reductive gestures approaches an endpoint with images like Treme (2010). Two blocky forms, white over blue, rest against a neutral gray and white background; they too are cast in plaster, and have been painted in simple vertical washes. Despite its reticent minimalism and its genesis within the walls of VanDerBeek’s studio, the picture has a real-world referent: its juxtaposition of colors mimics the stairway outside an abandoned modernist schoolhouse the artist encountered in the Treme neighborhood of New Orleans.

Treme is part of To Think of Time, the three-part suite of new photographs (all 2010) comprising VanDerBeek’s first solo exhibition in a museum, presented last autumn at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. In advance of that show, VanDerBeek returned to the field, this time visiting two new sites that lend themselves to meditations on pastand present: NewOrleans, which was then about to mark the fifth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, and Baltimore, the artist’s hometown. The locations symbolize VanDerBeek’s attempt (begun with the work created after her foray to Detroit) to examine how both private and public memories are encoded in the physical environments we inhabit. Inspired by the observational acuity and sensitivity of Walt Whitman, from whom two of the exhibition’s photographic arrangements draw their titles (Song of Myself and Sleepers), the roughly three dozen smallscale images present fragments, whether captured in the field or constructed in VanDerBeek’s Brooklyn studio. In the image Treme School Window, one windowpane opens to reveal a metaphorical black hole at the center of the composition. Another, Baltimore Window, depicts an antique leaded window, exhumed from dusty seclusion in the basement of the artist’s childhood home, resting in a slot carved into a rectangular block of plaster; a narrow shaft of light cuts through the window and falls directly behind it onto the wall.

Such resonant images, gathered into a halting frieze around the Whitney’s first-floor gallery, were punctuated by nearly abstract photographs of building foundations in New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward. The concrete slabs carry evidence of the houses they supported, such as rust-caked holes into which rebar once slotted, and the scrapes and gouges left behind by the storm. As VanDerBeek told exhibition curator Tina Kukielski, “I felt when looking down upon them for the first time that these foundations retained in their surfaces the entire history of our civilization. They reminded me of early pictographs, and with their pale fragments of color and texture, they echoed the images of fractured frescoes or ancient Greek or Roman art.” The works’ grayscale tones are joined by hints of dusky blue or sunrise pink, indicative of the natural light in which all the images, whether shot inside or outside the studio, were made. The light itself is a subtle indicator of time’s passage. Reading the installation from left to right, the amount of light in each image gradually rises and then dissipates. It would be easy to extrapolate from this sunrise-tosunset narrative a tragic tale of decay: urban infrastructure enters into terminal decline, its only remaining function to bear noble witness to the lives lived in its midst. But to do so would be to neglect an idea that the generative, studio-based half of VanDerBeek’s work speaks to: around the corner there is always a new dawn.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

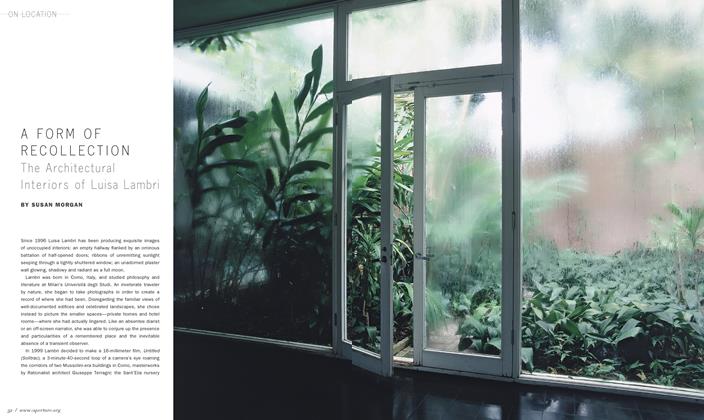

On Location

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

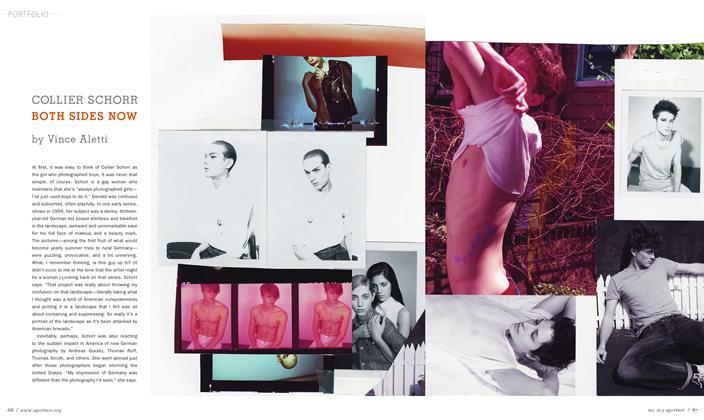

Portfolio

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

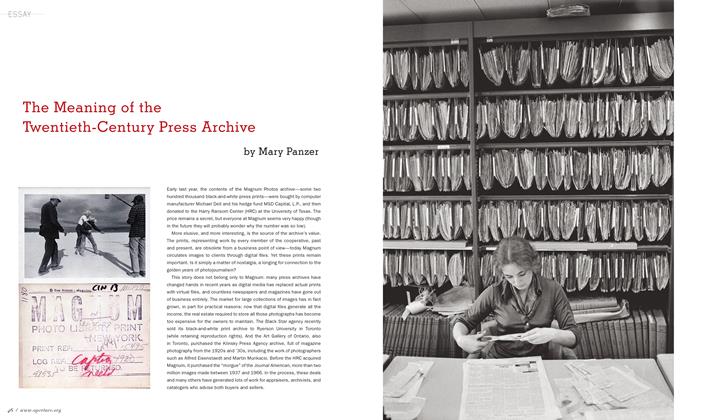

Essay

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Archive

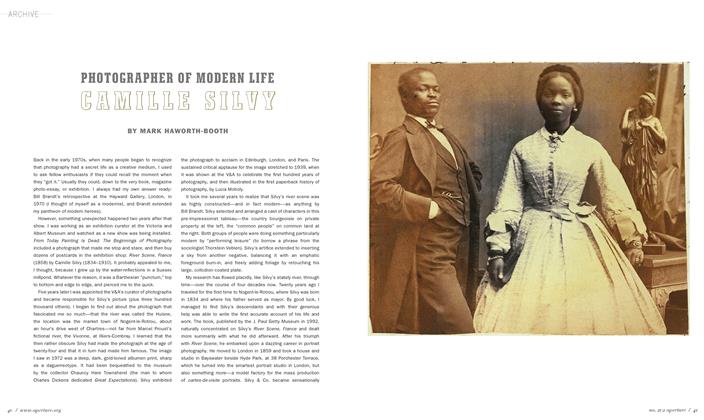

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Brian Sholis

-

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016 -

Redux

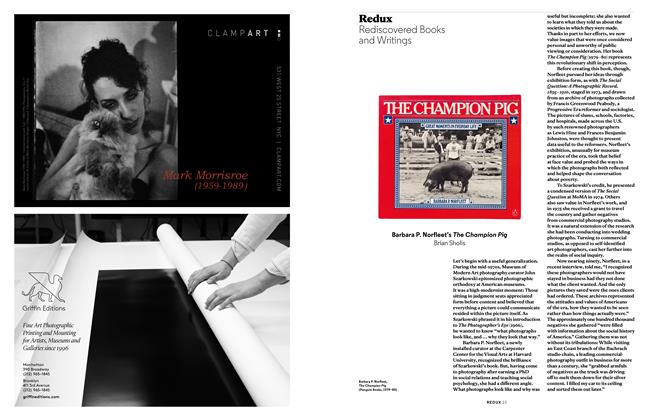

ReduxBarbara P. Norfleet's The Champion Pig

Spring 2015 By Brian Sholis -

Pictures

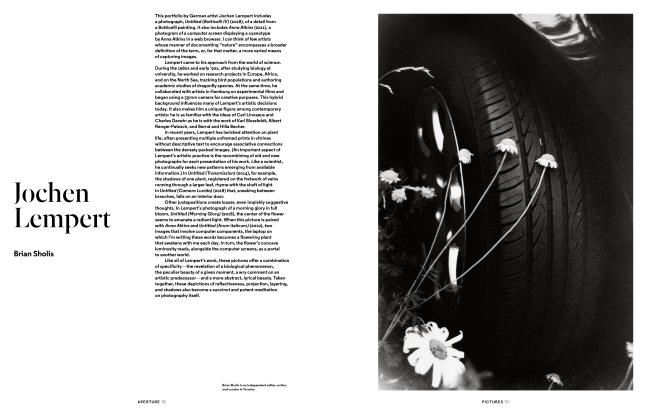

PicturesJochen Lempert

Spring 2019 By Brian Sholis -

Words & Pictures

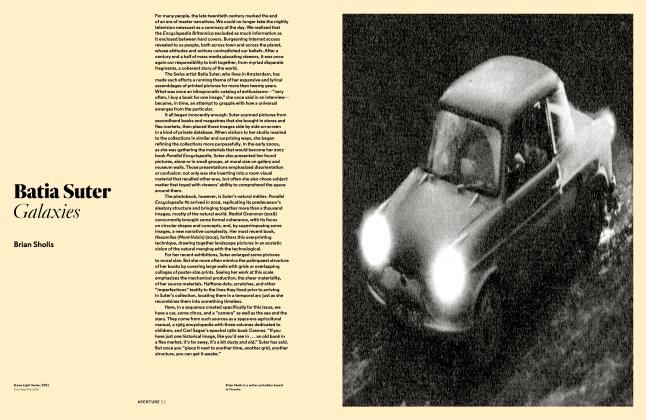

Words & PicturesBatia Suter

Fall 2021 By Brian Sholis -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWJeff Weber

FALL 2022 By Brian Sholis -

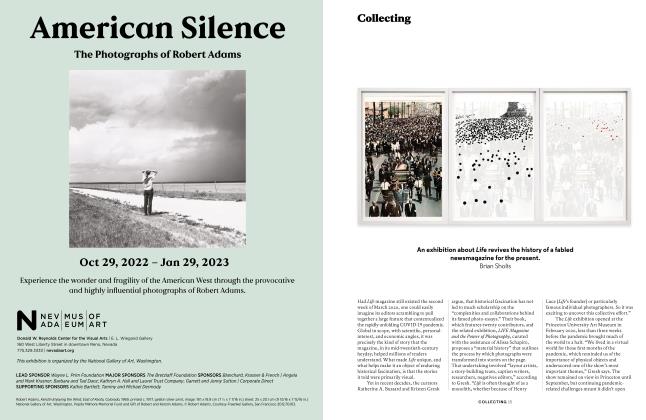

Collecting

WINTER 2022 By Brian Sholis

Mixing The Media

-

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaPhotos On The Grass (at Last)

Winter 2001 -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaThe Author As Photographer Early Soviet Writers And The Camera

Winter 2008 By Erika Wolf -

Mixing The Media

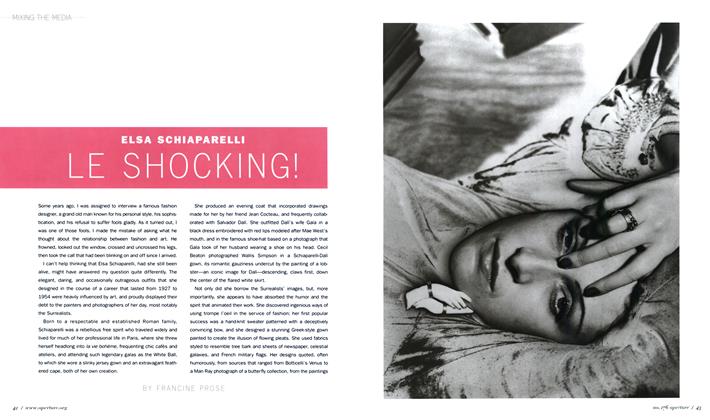

Mixing The MediaElsa Schiaparelli Le Shocking!

Fall 2004 By Francine Prose -

Mixing The Media

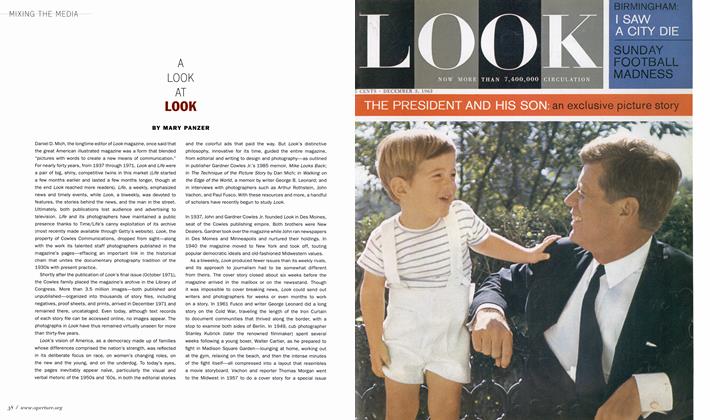

Mixing The MediaA Look At Look

Summer 2009 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

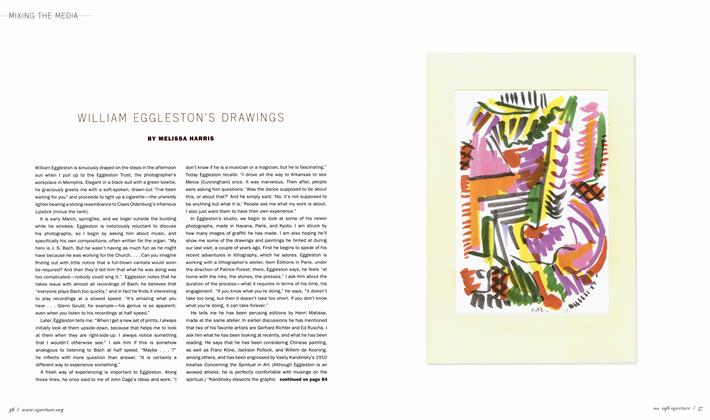

Mixing The MediaWilliam Eggleston's Drawings

Fall 2009 By Melissa Harris -

Mixing The Media

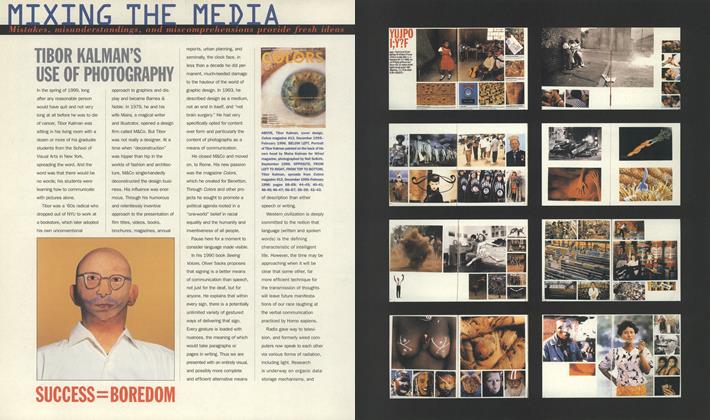

Mixing The MediaTibor Kalman’s Use Of Photography

Spring 2000 By Neil Selkirk