LAURIE ANDERSON'S RHYTHMIC EYE

MIXING THE MEDIA

I have this theory of the rhythmic eye. I use my eyes as though they are video cameras. I see both still and moving images in a constant stream. I never really lock on a single image. ”—Laurie Anderson

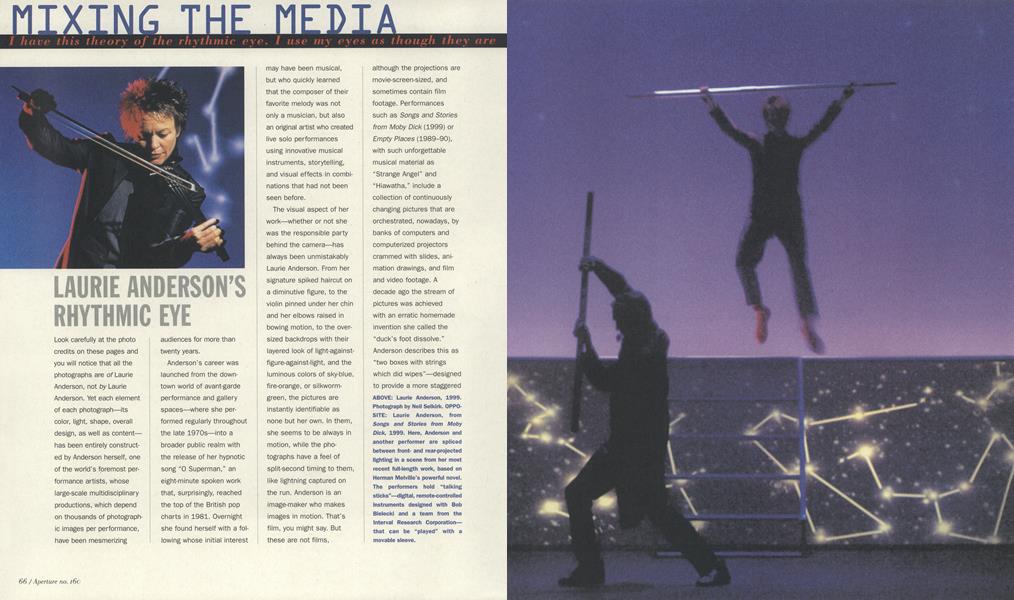

Look carefully at the photo credits on these pages and you will notice that all the photographs are of Laurie Anderson, not by Laurie Anderson. Yet each element of each photograph—its color, light, shape, overall design, as well as content— has been entirely constructed by Anderson herself, one of the world’s foremost performance artists, whose large-scale multidisciplinary productions, which depend on thousands of photographic images per performance, have been mesmerizing audiences for more than twenty years.

Anderson’s career was launched from the downtown world of avant-garde performance and gallery spaces—where she performed regularly throughout the late 1970s—into a broader public realm with the release of her hypnotic song “0 Superman," an eight-minute spoken work that, surprisingly, reached the top of the British pop charts in 1981. Overnight she found herself with a following whose initial interest may have been musical, but who quickly learned that the composer of their favorite melody was not only a musician, but also an original artist who created live solo performances using innovative musical instruments, storytelling, and visual effects in combinations that had not been seen before.

The visual aspect of her work—whether or not she was the responsible party behind the camera—has always been unmistakably Laurie Anderson. From her signature spiked haircut on a diminutive figure, to the violin pinned under her chin and her elbows raised in bowing motion, to the oversized backdrops with their layered look of light-againstfigure-against-light, and the luminous colors of sky-blue, fire-orange, or silkwormgreen, the pictures are instantly identifiable as none but her own. In them, she seems to be always in motion, while the photographs have a feel of split-second timing to them, like lightning captured on the run. Anderson is an image-maker who makes images in motion. That’s film, you might say. But these are not films,

although the projections are movie-screen-sized, and sometimes contain film footage. Performances such as Songs and Stories from Moby Dick (1999) or Empty Places (1989-90), with such unforgettable musical material as “Strange Angel” and “Hiawatha,” include a collection of continuously changing pictures that are orchestrated, nowadays, by banks of computers and computerized projectors crammed with slides, animation drawings, and film and video footage. A decade ago the stream of pictures was achieved with an erratic homemade invention she called the “duck’s foot dissolve.” Anderson describes this as “two boxes with strings which did wipes”—designed to provide a more staggered effect and to break up what she refers to as “the tyranny of the rectangle,” an obsession that continues to absorb her as computer screens have come to dominate every aspect of daily life. Sometimes the duck’s foot dissolve’s bright white light threw an enormous shadow of Anderson’s clenched fist against a wall, at others a nearly invisible beam caught a projected slide midair when she waved her bow quickly in front of it. “So simple, so beautiful,” she says of its operation.

Anderson’s photographsin-motion are never still, and she is not interested in “still photography” per se. Photographs of herself in performance, spliced between the camera’s lens and her filmand photobackdrops, may appear in print as documentary evidence of past performances (and are usually the only record; very few videos of her live performances exist). But these images are never exhibited or displayed separately. Even Anderson’s downtown New York loft attests to her overwhelming lack of interest in the single, framed image; except for large picture windows that face the Hudson River, and her banks of computers and recording instruments that line the studio, the walls are image-free. “When you’re trying to think of new ways of doing things, the last thing you want to see are images from your most recent production,” Anderson says.

Instead she concentrates on what it takes to fill a huge stage with two hours’ worth of prefabricated images. “Filling that kind of space is an anxiety,” the artist says, “but I’m less concerned with spanning time than with tempo.” The endless stream of visuals, which are also a mix of words and ideograms, handdrawn stick figures and floating letters, do not illustrate the music so much as lead it. They provide the basic beat of a work—“your eyes

are the rhythm section,” she says—and force viewers to watch closely: one of her goals is for image and music to be read exactly on a par. Toward this end, she acknowledges, the method for constructing the grand For this artist, whose talents lie equally in music and fine arts, seeing and hearing are simultaneous experiences. Her approach to the separate disciplines of music and visual art is always a symbiotic combination of the two. “You know,” one of Anderson’s stories begins, “people often ask me whether I’m a filmmaker or a musician and it always reminds me of that question: ‘So if you could have the choice between having no eyes and no ears, which would it be?’ I could never really decide.”

visual design of her stage resembles musical composition, with its phrasing and measures and beats per minute. “The duration of the image follows the overall ‘arc’ of the piece,” she explains, linking this idea to what she calls her “theory of the rhythmic eye.” “I use my eyes as though they are video cameras,” Anderson says. “I see both still and moving images in a constant stream. I never really lock on a single image.”

Probably it is because she is always inside her images, and constantly on the move—singing, talking into a range of mikes and harmonizers, and operating electronic instruments onstage—that she has such a deeply visceral connection to the material of photography itself, to the substance of light. She is intensely aware of her body both as a screen—how it stops and bends light—and as a projector—how shadows bounce off of her. She is also fascinated by the ways verbal narratives (her stories and songs and the segues between them) and pictures embed themselves in the mind’s eye. In fact it was an observation she made early on, as an art history student at Barnard College in the mid-sixties, that was a springboard to the performance form she uses today: the impact of large, light-projected pictures, and the storytelling voice of an inspired professor. From her early experiments with pinhole photographs and fake holograms in the mid-seventies, to the indelible images of her eight-hour opus United States (1983), to her recent installation Storie Dal Vivo (1998) and the performance Songs and Stories from Moby Dick, Anderson has, over the course of three decades, constructed an extraordinary oeuvre of material made of light. “Photography,” she says, “is just another way of using light.”

RoseLee Goldberg

based in part on exclusive interviews with Laurie Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Essay

EssayBlue Mist

Summer 2000 By Charles Bowden -

Profile

ProfileA World Out Of Balance Necessary Truths

Summer 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessChuck Close Daguerreotypes

Summer 2000 By Lyle Rexer -

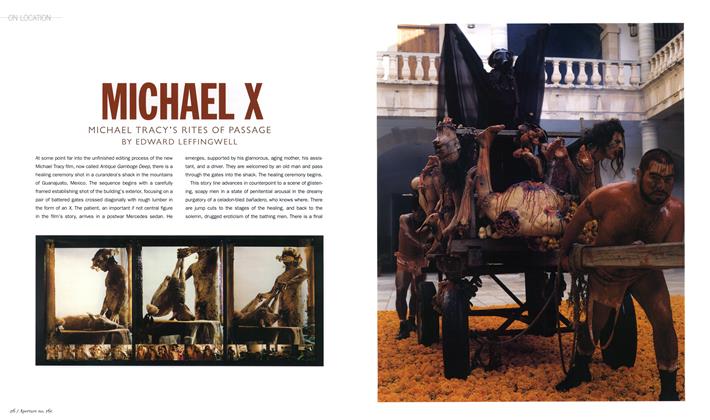

On Location

On LocationMichael X

Summer 2000 By Edward Leffingwell -

Before The Lens

Before The LensLatent Image

Summer 2000 By Michael L. Sand, Yoshio Uemura -

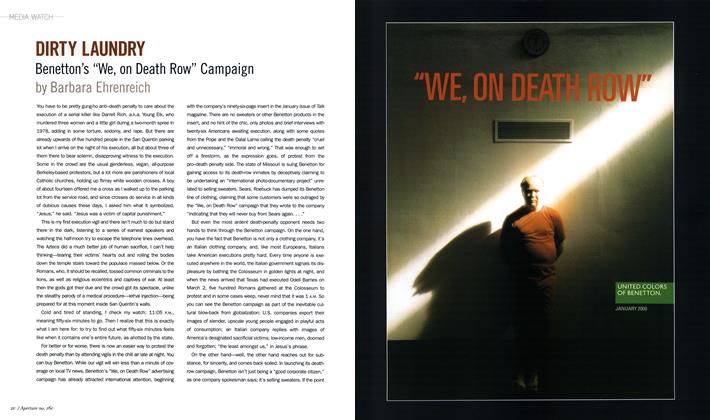

Media Watch

Media WatchDirty Laundry

Summer 2000 By Barbara Ehrenreich

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Roselee Goldberg

Mixing The Media

-

Mixing The Media

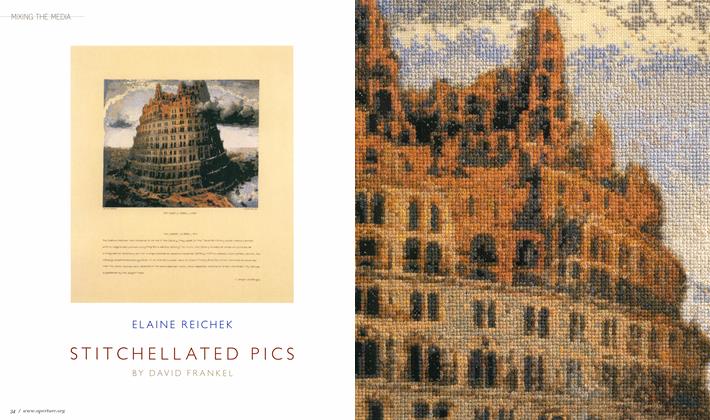

Mixing The MediaElaine Reichek Stitchellated Pics

Summer 2004 By David Frankel -

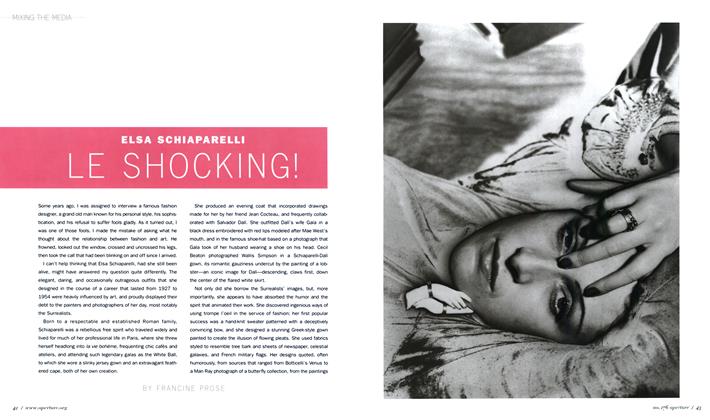

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaElsa Schiaparelli Le Shocking!

Fall 2004 By Francine Prose -

Mixing The Media

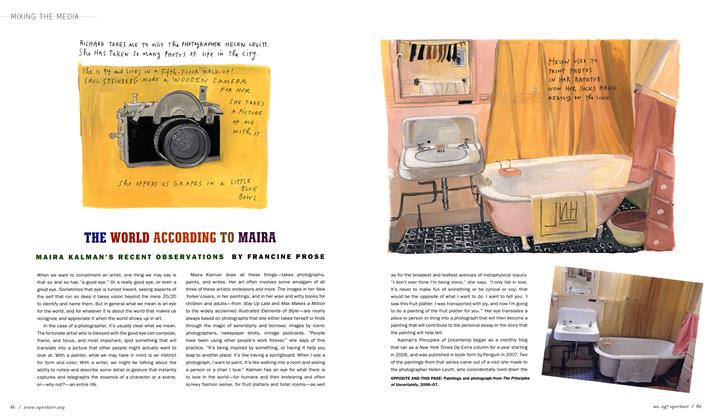

Mixing The MediaThe World According To Maira

Winter 2009 By Francine Prose -

Mixing The Media

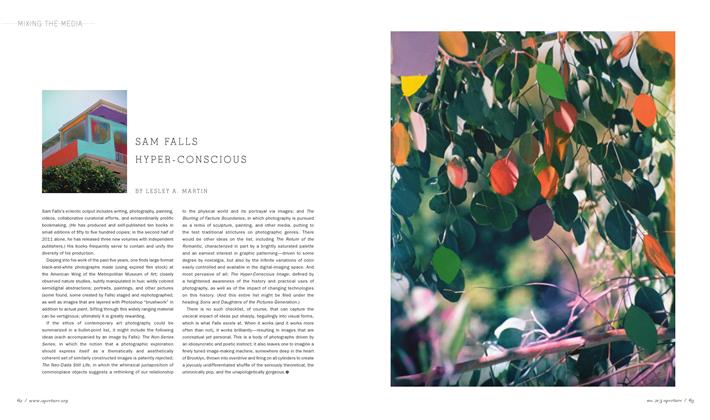

Mixing The MediaSam Falls Hyper-Conscious

Winter 2011 By Lesley A. Martin -

Mixing The Media

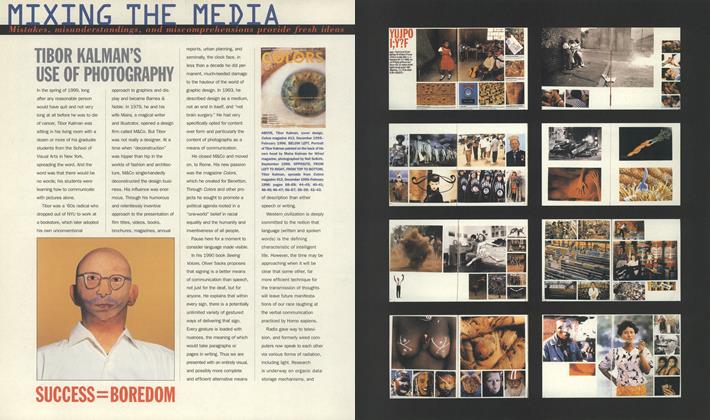

Mixing The MediaTibor Kalman’s Use Of Photography

Spring 2000 By Neil Selkirk -

Mixing The Media

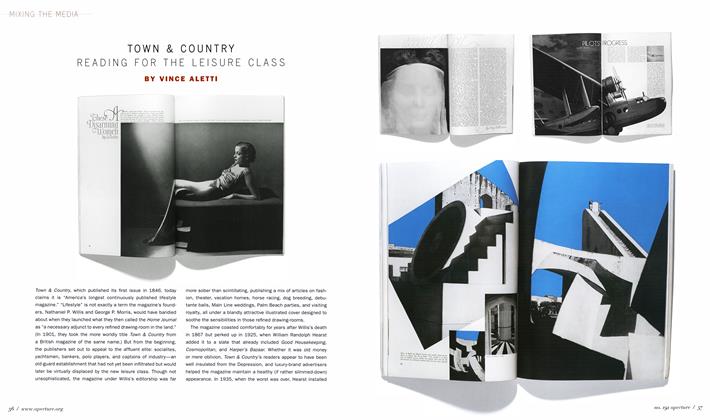

Mixing The MediaTown & Country Reading For The Leisure Class

Summer 2008 By Vince Aletti