HANATSUBAKI PERFECTION IS LIFELESS

MIXING THE MEDIA

JASON EVANS

A red-haired girl lies along a dirt furrow in a beetle-bright Prada dress that looks like it shrank in the hot wash. Arranged around her, green salad bowls overflow with green salad. I am executing an idea sketched by revered Japanese graphic designer Nakajo Masayoshi for issue 695 of Hanatsubaki magazine. He has worked on the publication since the mid-1960s, expounding his surreal and playful vision and helping to transform a corporate giveaway into a thrilling visual trip. He became the publication’s art director in 1975, and still holds the position today, as an energetic and stylish seventy-four-year-old. My own work photographing for Hanatsubaki took me to Tokyo, where I recently had a look in the magazine’s extraordinary archive.

Established in 1937, Hanatsubaki evolved from customer-care/ advice pamphlets that Shiseido began publishing in 1924. Initially named Shiseido Monthly, these publications became ShiseidoGraph in 1933, before settling on the name Hanatsubaki, meaning “camellia flower” (the company’s logo). The magazine was distributed for free (until 1985) to registered Shiseido customers, known as the Camellia Club, who were encouraged to keep a log of their cosmetics purchases and receive advice from their local, specially trained Shiseido pharmacist. At one point there were some twenty thousand Shiseido stores in Japan. The company was an innovator in its field, introducing a range of colored face powders—a lilac hue, a green-hinted white—whereas only plain white had previously been available. They also introduced the first lead-free powders to the Japanese market.

The first president of Shiseido, Fukuhara Shinzo (the son of Fukuhara Arinobu, who founded the company in 1887), was a forward thinker who had studied in North America and Paris, where he was influenced by the Art Nouveau and Art Deco movements. Upon his return to Japan Fukuhara Shinzo shared his firsthand knowledge of Western styles, which became filtered through Japanese sensibilities. A photographer in his own right, he had published five books of photography by 1937, and contributed images to the early Shiseido pamphlets.

Fukuhara’s progressive thinking, and its impact on company philosophy, created a magazine that encouraged Japanese women to embrace independence, through depictions of untethered lifestyles. Of course, the magazine’s aim was also to groom a client base for Shiseido. Early issues feature excruciating how-to photoseries on cosmetics application and hair care; the models appearing in these guides grimace in trepidation at their transformation— one senses coercion rather than voluntary choice.

A healthy, vigorous lifestyle has been portrayed from the beginning and throughout the magazine’s history—translated through the varied aesthetic conditions of passing decades (with a publishing hiatus from 1940 to 1950), and a gradual rise in urban locations, eventually overtaken by “postmodern” narratives beginning in the 1980s. The very first cover of Hanatsubaki in 1937 depicted two Japanese women outdoors, one in “traditional" dress, the other in Western garb, partly obscured by a shrub from behind which they emerge. Both women gaze confidently off into the distance— perhaps toward their future. One is tempted to read this preliminary image as some kind of manifesto in a visual culture that emphasizes attention to detail and an interrelationship between content and sign. The photographer of this image, like most photographers in subsequent issues, remains uncredited—photography was seen for many years in Japan as merely craft. (Those whose names are known include Sato Akira, Takanashi Yutaka, Sukita Masayoshi, and Kogure Toru.)

One striking thing about the magazine’s early covers—all designed in-house—is the wide range of styles and subject matter: the lack of a consistent format. In the interior pictorial essays there were, however, recurring themes. A popular one up until the mid-1960s was the jolly day out in the country: driving, biking, camping, exercising, boating, and swimming belles enjoy one another’s company in an otherwise deserted landscape. There is also the occasional visit to a museum, archaeological ruin, or art gallery. Seldom do we see a man in these idyllic, wholesome scenes. One is struck by the independence of these female characters— they are reminiscent of the newly active and confident image of European women after World War II. And there is not a whiff of romance in these early pages. Today, it is hard to imagine a fashion magazine void of sensual innuendo; indeed, what was novel or challenging in the work of Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton in the 1970s has now become so de rigueur as to have lost its punch.

These active representations are at odds with the Western stereotype of the passive, repressed Japanese woman. It would be naïve to say that the magazine played a central role in transforming gender roles in Japanese society at large, but Hanatsubaki's enormous

circulation suggests a staggering cultural impact, at least among women. At the height of its distribution in the late 1960s the publication had a circulation of six million, which means that more than 10 percent of the country’s female population were subscribers. (Of course, it helped that the magazine was distributed for free.) Irreverent, visually inventive, and quite wonderful, Hanatsubaki deserves a place in any survey of the 1960s international cultural revolution, alongside titles like Twen and Nova in the chapter on fashion magazines. This was no reading material for squares.

We in the West may have been encouraged to imagine postwar Japan as rather cold and conservative, but recently rediscovered photographic material paints a radically different picture of the time. From Mike Nogami’s rockers and Yoshiyuki Kohei’s “peepers" to Yanagisawa Shin’s depictions of drunken antics and Ogawa Takayuki’s transsexual stories—a great variety of lifestyles have come to light. If we compare the images in Hanatsubaki with work appearing in simultaneously published editions of the groundbreaking Japanese journal The Photo Image, we can see it was every bit as varied, rich, experimental, and idiosyncratic.

The transformation of Hanatsubaki from cosmetics newsletter to full-blown culture magazine is largely attributable to Nakajo, who joined Shiseido’s design team in 1956 and began working on the magazine a decade later. In the late 1960s he proposed articles on a broad range of subjects including art and design, cinema and literature, along with fashion stories. He often chose a particular photographer according to his or her ability with particular formats, subsequently commissioning according to his evaluation of their particular strengths.

For the past four years, Nakajo has been offering me assignments that seem to be based on a mischievous understanding of what I would not normally do—I generally prefer to photograph men’s styles, but he invariably puts me to work on women’s. He gently pushes me into new territory, with a smile and a shrewd assessment of what I am actually capable of.

Nakajo’s anarchic approach to design can perhaps be understood in some of his maxims: “Perfection is lifeless. Design is like creating one corpse after another. Third-rate things inspire most. Masterpieces are born by chance. Talent is not a potato—real talent is the ability to be both a carrot and a cabbage. Craftsmanship makes me sick.” His attitude to photography is formalist and pragmatic: he sees it as a changeable medium, and felt it was particularly so in the “radical and dramatic” 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

Nakajo’s personality-driven approach to art direction is not dissimilar to that of the Dutch magazine maverick Jop van Bennekom, whose character is felt right through the editorial content of his titles Re-, Butt, and Fantastic Man. Both men take content as a point of departure, a guiding reference, and both have a deep love of the magazine as a unique and vital medium. Furthermore, they both enjoy a generously ambiguous relationship with the “control” of photographers, tending to issue rather terse assignment descriptions, in the end accommodating the ideas and images that are actually produced in the shoot. Nakajo constantly surprises me with his sheer passion for life. His secret as one of Japan’s most respected art directors is, he says, simply “curiosity." When we look at the consistently inconsistent layouts, the surprising image combinations, and the effortless, elegant use of type, we may be forgiven for thinking we are seeing design as a formal inventory of his editorial experience.

These days a typical editorial meeting at a fashion magazine usually begins not with fashion editors’ and art directors’ story concepts but with the presentation of a list of advertisers whose recent collections need to be included to keep the relevant backs appropriately scratched. Contemporary fashion magazines are in danger of becoming mere vehicles for advertising; their editorials are the palatable padding that reiterates the brand ads, at a fraction of the production costs. Hanatsubaki, by contrast, relies only on Shiseido funding, and carries no advertisements but their own—just two per issue as a rule, usually designed in-house. As a photographer working for them, I have never been requested to include, endorse, or otherwise engage with any Shiseido product, and all editorial discussions have been conceptually driven. This model of corporate altruism is sadly lacking elsewhere, and to me implies a breakdown in the human, idiosyncratic history of fashion photography.

I was a recipient of Shiseido’s extraordinary corporate commitment to emerging artists even before working with Hanatsubaki. In 2002 I was sent around the world in two months (following the route of my choice) for their La Beauté gallery in Paris, on the condition that I photograph something I found beautiful every day. All expenses paid. No questions asked. The images were dutifully displayed, sent out live via the Internet, and despite occasional queries about my subject, my vision was always honored.

I have now all but withdrawn from the editorial fashion system. As much as I enjoy the representation of style and the manifestation of cultural speculation possible in the fashion photography context, there are too few magazines left where this kind of work can find a home. Hanatsubaki is one of those places.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueInvasion 68: Prague

Fall 2008 By Melissa Harris -

On Location

On LocationJoel Sternfeld: Oxbow Archive

Fall 2008 By Gretel Ehrlich -

Media Watch

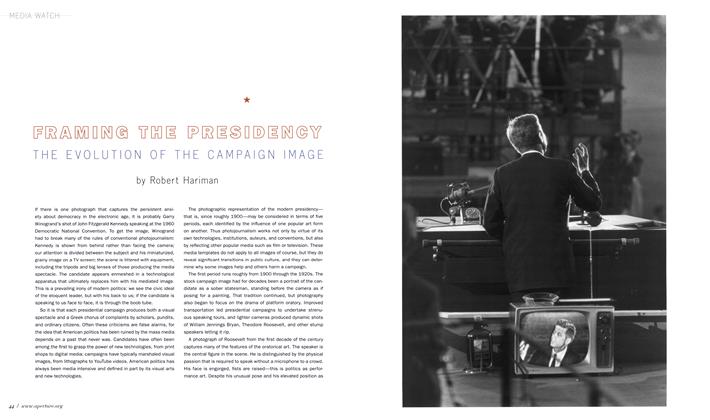

Media WatchFraming The Presidency The Evolution Of The Campaign Image

Fall 2008 By Robert Hariman -

Work And Process

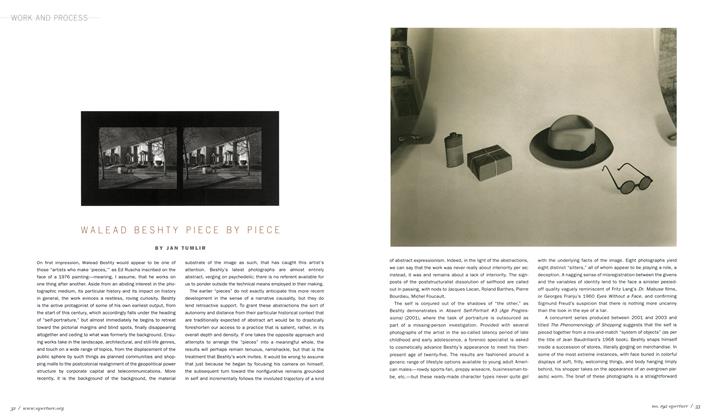

Work And ProcessWalead Beshty Piece By Piece

Fall 2008 By Jan Tumlir -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectDuane Michals: Chromophilia

Fall 2008 By Robert Kushner -

Work In Progress

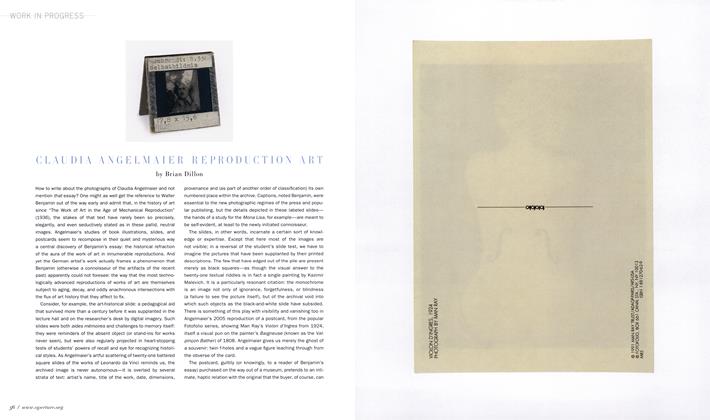

Work In ProgressClaudia Angelmaier Reproduction Art

Fall 2008 By Brian Dillon

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jason Evans

-

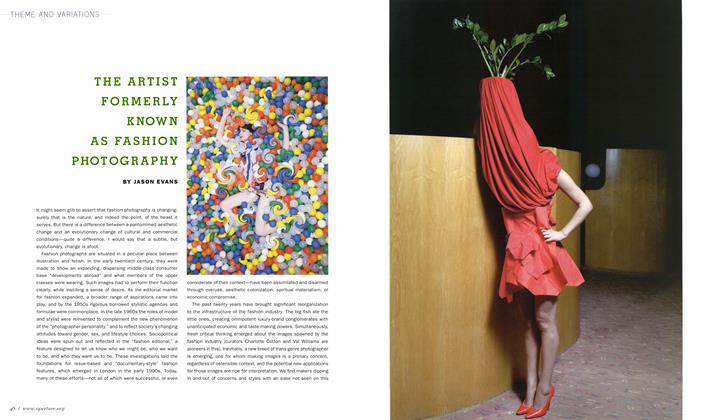

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsThe Artist Formerly Known As Fashion Photography

Summer 2009 By Jason Evans -

Reviews

ReviewsVan Lamsweerde & Matadin: Pretty Much Everything

Spring 2011 By Jason Evans -

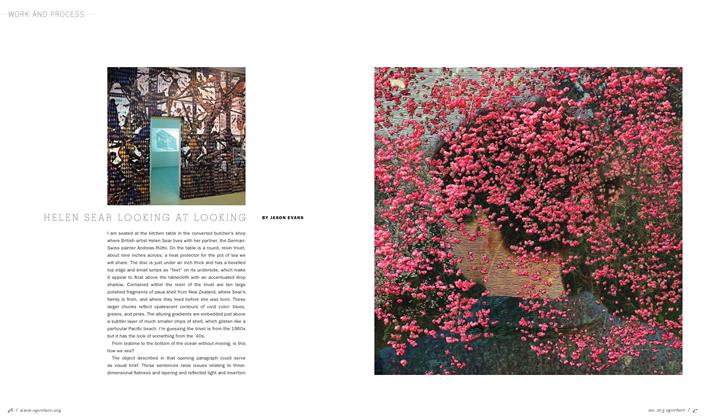

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHelen Sear Looking At Looking

Summer 2011 By Jason Evans -

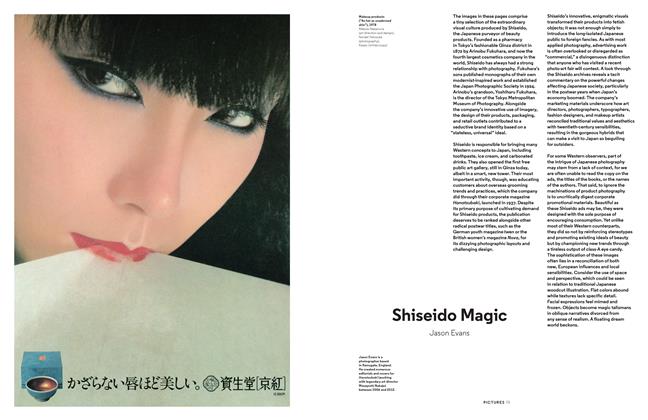

Pictures

PicturesShiseido Magic

Fall 2014 By Jason Evans

Mixing The Media

-

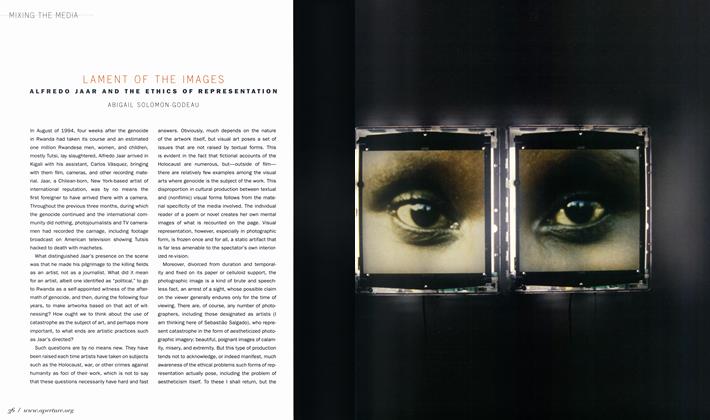

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaLament Of The Images

Winter 2005 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Mixing The Media

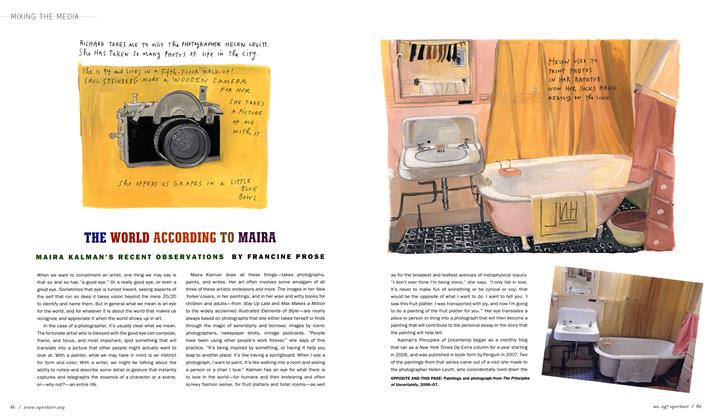

Mixing The MediaThe World According To Maira

Winter 2009 By Francine Prose -

Mixing The Media

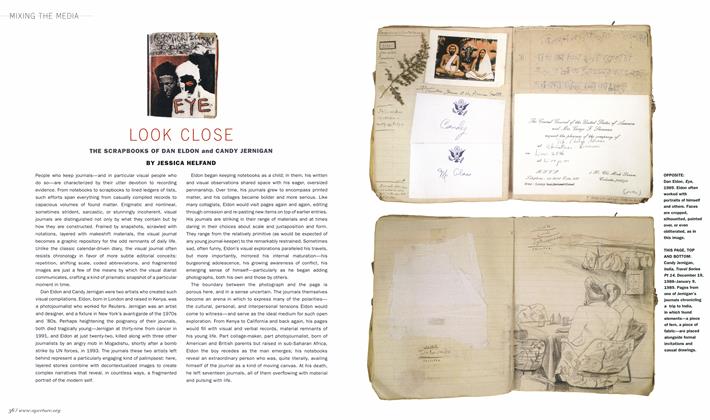

Mixing The MediaLook Close The Scrapbooks Of Dan Eldon And Candy Jernigan

Spring 2009 By Jessica Helfand -

Mixing The Media

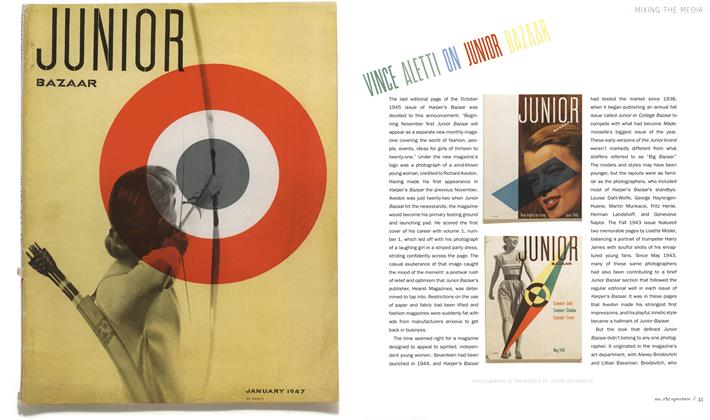

Mixing The MediaJunior Bazaar

Spring 2006 By Vince Aletti -

Mixing The Media

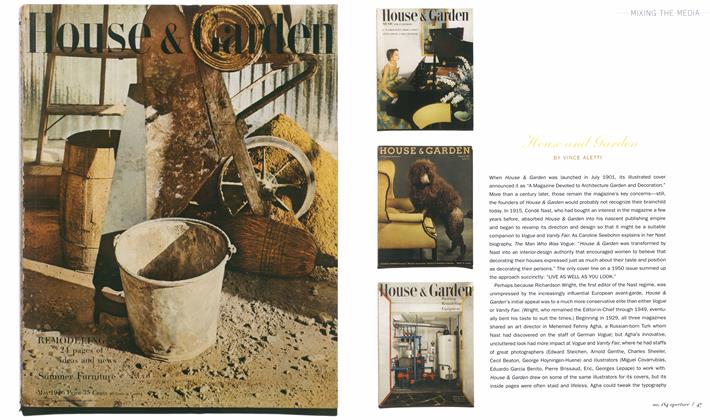

Mixing The MediaHouse And Garden

Fall 2006 By Vince Aletti