Selected Books

Molly Rogers Delia's Tears: Race, Science And Photography In Nineteenth-Century America

Spring 2011Molly Rogers DELIA'S TEARS: RACE, SCIENCE AND PHOTOGRAPHY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICA

New Plaven: Yale University Press, 2010

When in 1976 fifteen daguerreotypes of black men and women were discovered in the attic of the Peabody Museum, the question of their meaning and purpose was immediately raised. The images were clearly unusual in that they were not like most daguerreotypes made in America: they did not depict white middle-class men and women posing for the camera. ...No, these stark and bloodless images were not portraits; they were about something else—but what?

(continued on next page)

(Delia's Tears continued)

Attached to several of the daguerreotypes when they were discovered were hand-written labels. These provided the first clues to uncovering the meaning of the images. The labels give the name of each person photographed, the African ethnic group to which he or she was apparently related, and the name of his or her “owner.” The people in the photographs, this information revealed, were slaves who lived in or near Columbia, South Carolina. . . . Why, when photography was still a rather new and complicated undertaking— and used almost exclusively for portraiture—did someone bother to photograph slaves, people regarded as having little or no status, people who were not even considered Americans? . . . Understanding the meaning of Delia’s photograph requires familiarity with her world, the world of slave community, but also the very different worlds of the naturalist, the slaveholder, and the politician. . . . Only by considering what others wanted to see in the images—what they were perhaps looking for and why—can we begin to understand how an uncertain art comes to be useful to a science of desirable or detestable bodies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

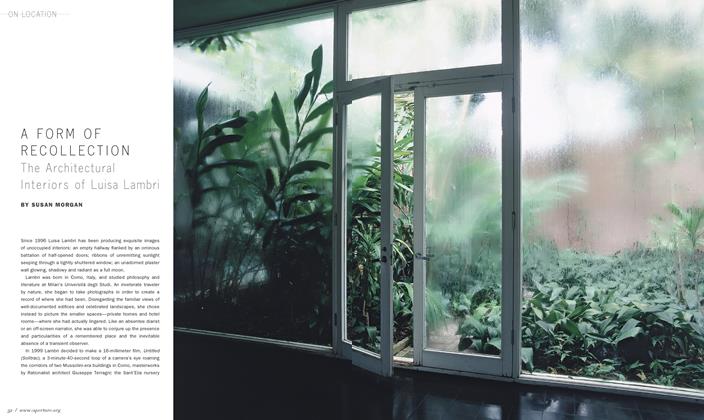

On Location

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

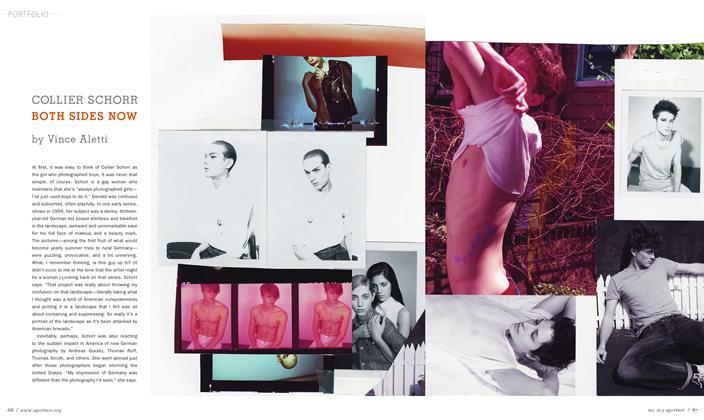

Portfolio

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessGeraldo De Barros Fotoformas

Spring 2011 By Fernando Castro -

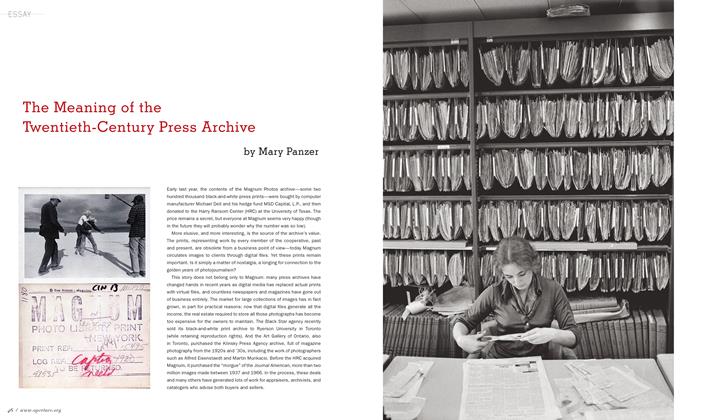

Essay

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

Archive

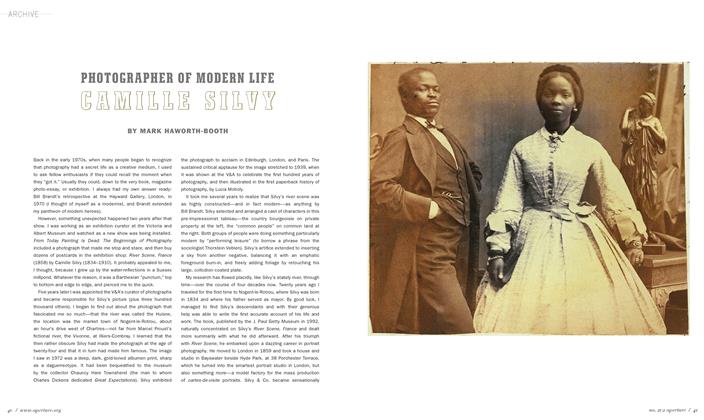

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Selected Books

-

Selected Books

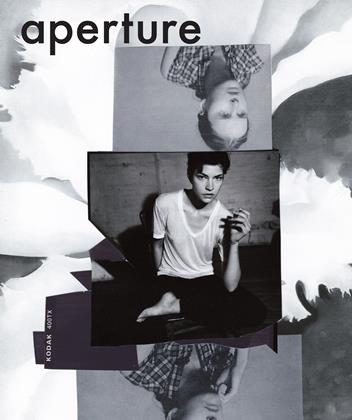

Selected BooksFrancesca Woodman

Fall 2007 -

Selected Books

Selected BooksLarry Towell: The World From My Front Porch

Fall 2008 -

Selected Books

Selected BooksOmar D Devoir De Memoire: A Biography Of Disappearance, Algeria 1992-

Fall 2008 -

Selected Books

Selected BooksDavid T. Hanson Colstrip, Montana

Spring 2011 -

Selected Books

Selected BooksLorna Simpson

Winter 2003 By Kellie Jones -

Selected Books

Selected BooksNorman Rockwell: Behind The Camera

Winter 2009 By Ron Schick