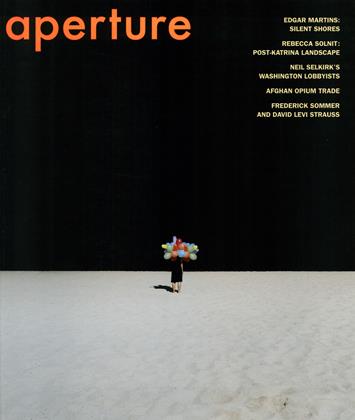

LISTENING TO PHOTOGRAPHY THE SILENCE OF EDGAR MARTINS

ON LOCATION

DAVID CAMPANY

The Surrealists did not get out much. Theirs was an agoraphobic art of highly charged intimacy. They saw the imagination as an unruly chamber, best evoked in tight, horizonless frames. When they did venture out, it was usually under cover of darkness, when the grip of social law is loose and the black backdrop of night can turn social space into a potential stage.

The Surrealists did take holidays, often by the sea. They had fun, but rarely made art to rival their urban efforts. Essentially bourgeois types, dividing city from country, work from leisure, they did not recognize themselves on the beach. It was a missed opportunity. After all, the beach is the porous boundary par excellence. Every surface is on the move. Substance and void blur. Light and time define each other. Desire strains to be set free. Space becomes a diagram of unnerving simplicity and vision is intensified. At night, even more so.

Few places in the world retain their character around the clock. Most depend on a particular time of day and a particular use. The more dependent they are, the more they seem to disappear from us at all other times. The beach is such a place. At night it is almost nothing of what it is by day. A beach without people may still be a beach, but when we can’t see the sea, what is it? To be on the beach at night is always to trespass a little—beyond official hours. To photograph it at night is always to transgress a little.

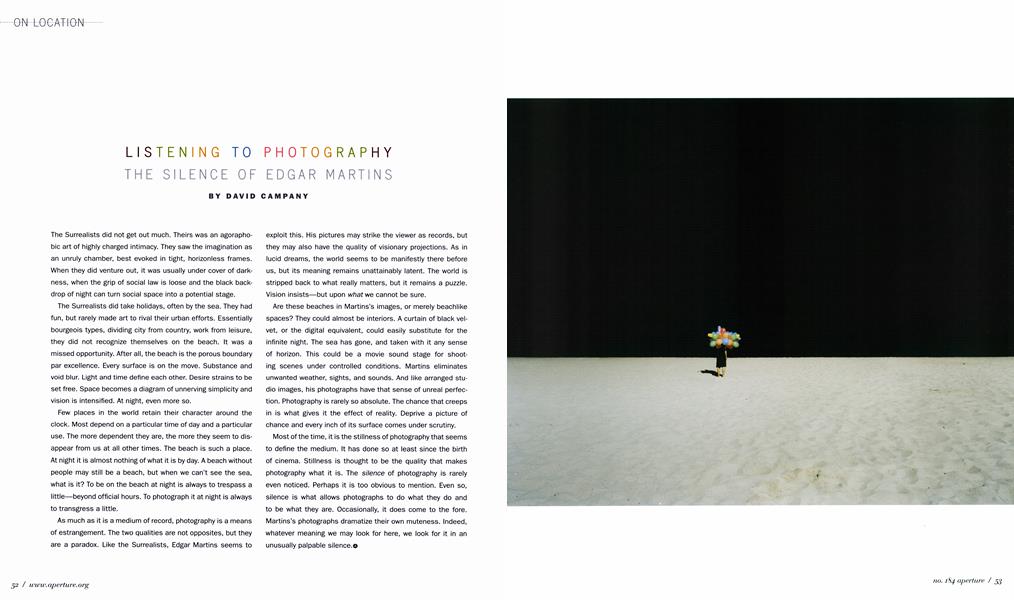

As much as it is a medium of record, photography is a means of estrangement. The two qualities are not opposites, but they are a paradox. Like the Surrealists, Edgar Martins seems to exploit this. His pictures may strike the viewer as records, but they may also have the quality of visionary projections. As in lucid dreams, the world seems to be manifestly there before us, but its meaning remains unattainably latent. The world is stripped back to what really matters, but it remains a puzzle. Vision insists—but upon what we cannot be sure.

Are these beaches in Martins’s images, or merely beachlike spaces? They could almost be interiors. A curtain of black velvet, or the digital equivalent, could easily substitute for the infinite night. The sea has gone, and taken with it any sense of horizon. This could be a movie sound stage for shooting scenes under controlled conditions. Martins eliminates unwanted weather, sights, and sounds. And like arranged studio images, his photographs have that sense of unreal perfection. Photography is rarely so absolute. The chance that creeps in is what gives it the effect of reality. Deprive a picture of chance and every inch of its surface comes under scrutiny.

Most of the time, it is the stillness of photography that seems to define the medium. It has done so at least since the birth of cinema. Stillness is thought to be the quality that makes photography what it is. The silence of photography is rarely even noticed. Perhaps it is too obvious to mention. Even so, silence is what allows photographs to do what they do and to be what they are. Occasionally, it does come to the fore. Martins’s photographs dramatize their own muteness. Indeed, whatever meaning we may look for here, we look for it in an unusually palpable silence.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

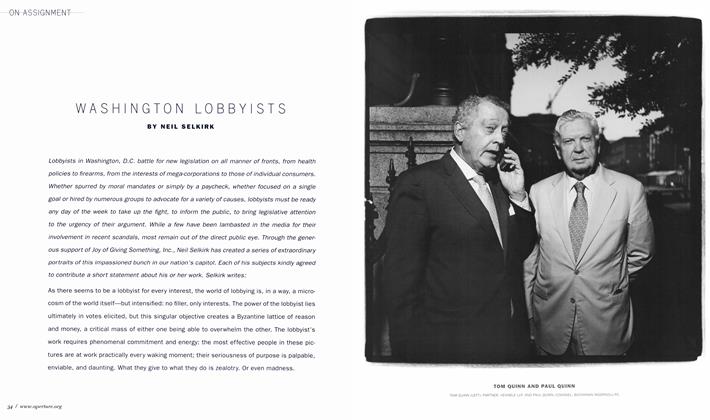

On Assignment

On AssignmentWashington Lobbyists

Fall 2006 -

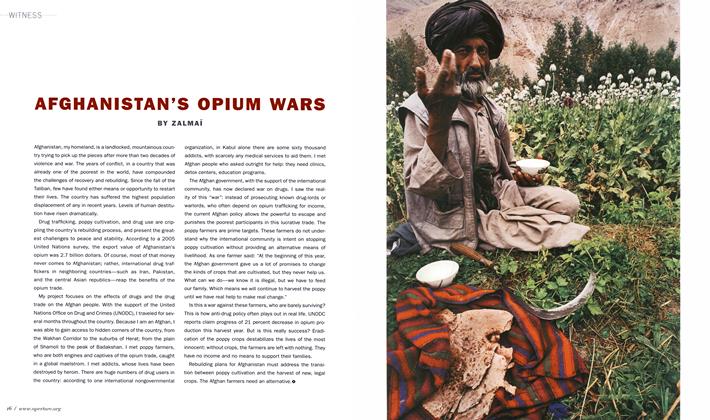

Witness

WitnessAfghanistan’s Opium Wars

Fall 2006 By Zalmaï -

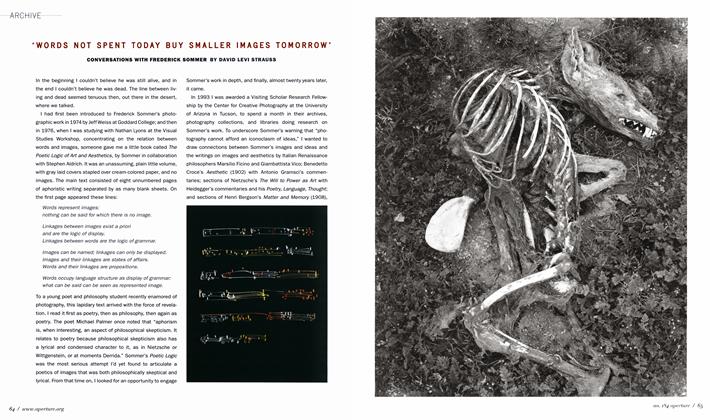

Archive

Archive"Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow"

Fall 2006 By David Levi Strauss -

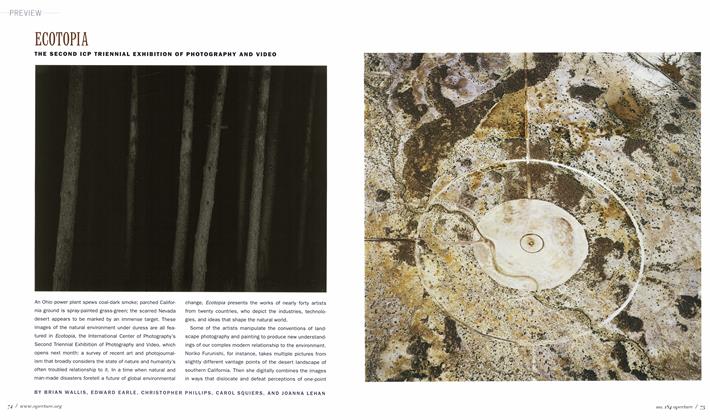

Preview

PreviewEcotopia

Fall 2006 By Brian Wallis, Edward Earle, Christopher Phillips2 more ... -

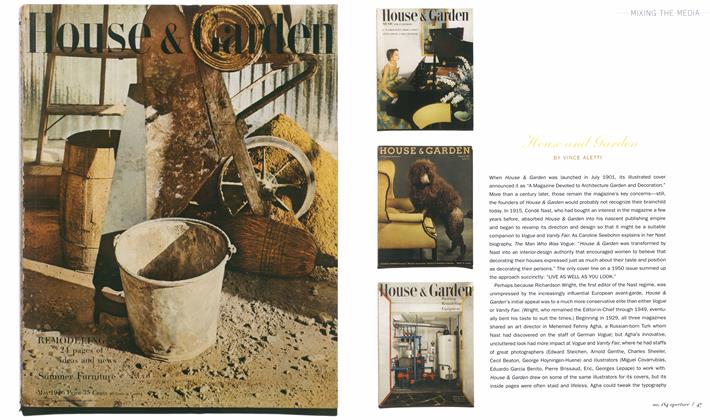

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaHouse And Garden

Fall 2006 By Vince Aletti -

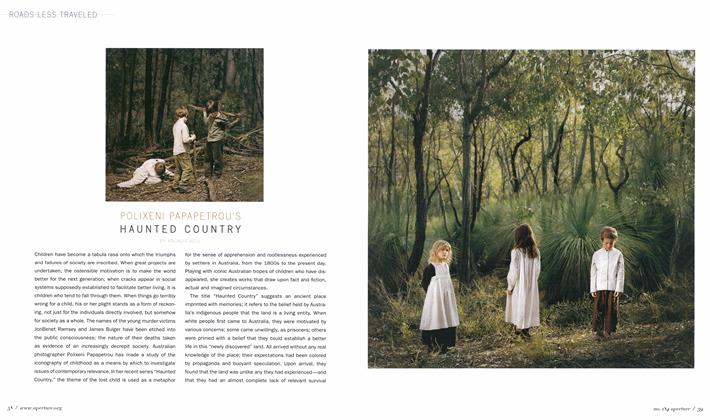

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledPolixeni Papapetrou’s Haunted Country

Fall 2006 By Anonda Bell

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

David Campany

-

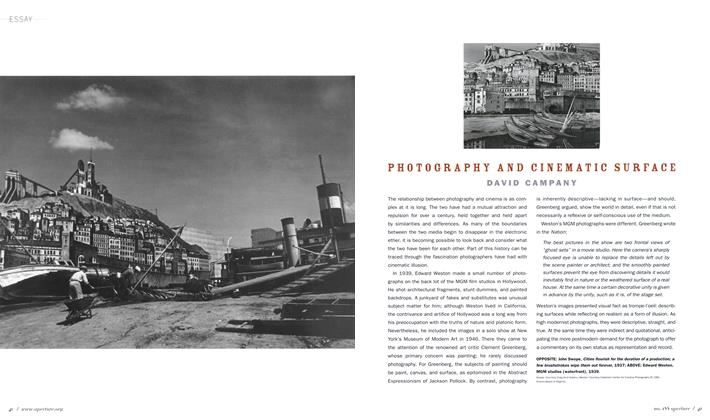

Essay

EssayPhotography And Cinematic Surface

Fall 2007 By David Campany -

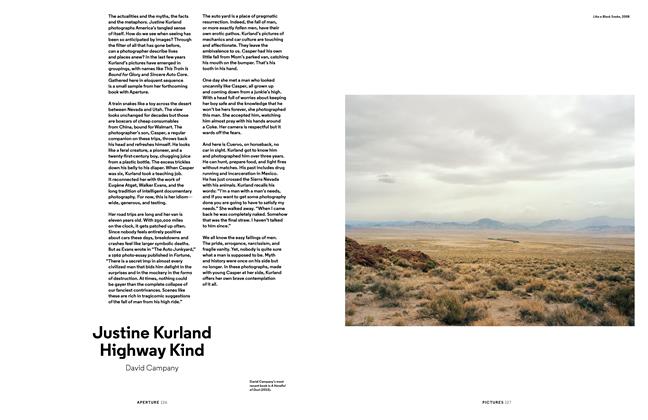

Pictures

PicturesJustine Kurland Highway Kind

Spring 2016 By David Campany -

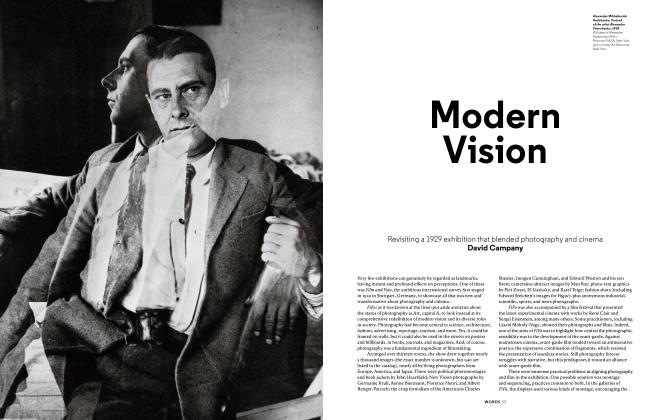

Words

WordsModern Vision

Summer 2018 By David Campany -

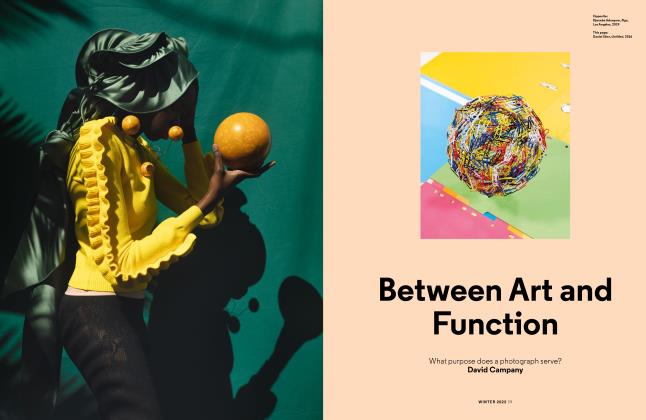

Between Art and Function

WINTER 2022 By David Campany -

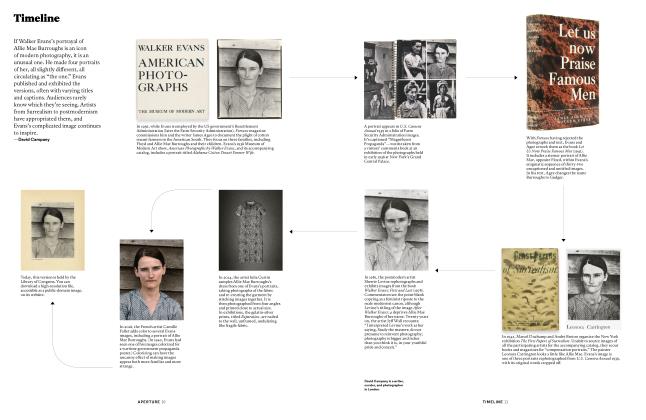

Timeline

SPRING 2023 By David Campany -

Off The Wall

SUMMER 2024 By David Campany, Sara Knelman

On Location

-

On Location

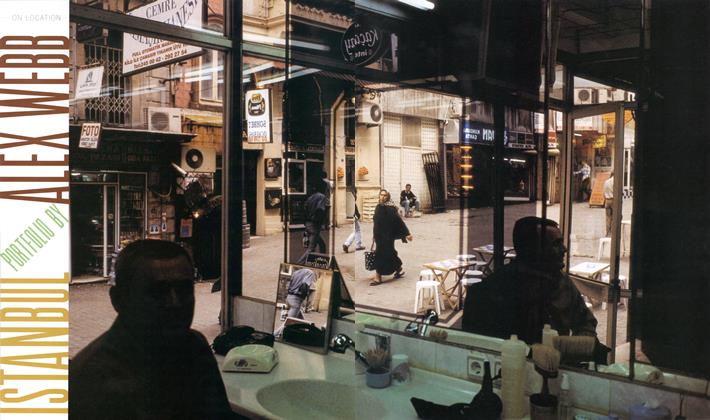

On LocationIstanbul Portfolio By Alex Webb

Winter 2005 -

On Location

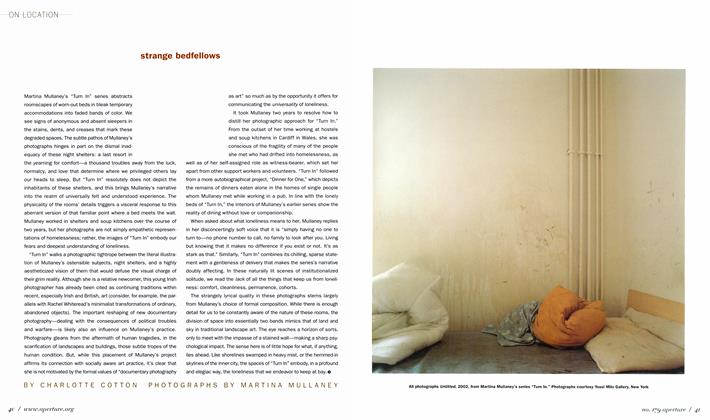

On LocationStrange Bedfellows

Summer 2005 By Charlotte Cotton -

On Location

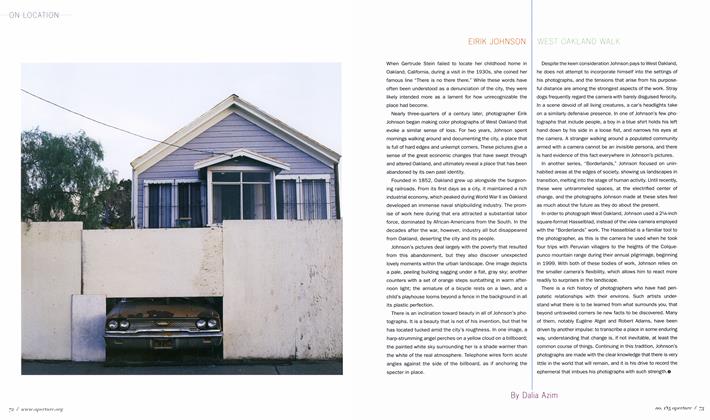

On LocationEirik Johnson West Oakland Walk

Winter 2006 By Dalia Azim -

On Location

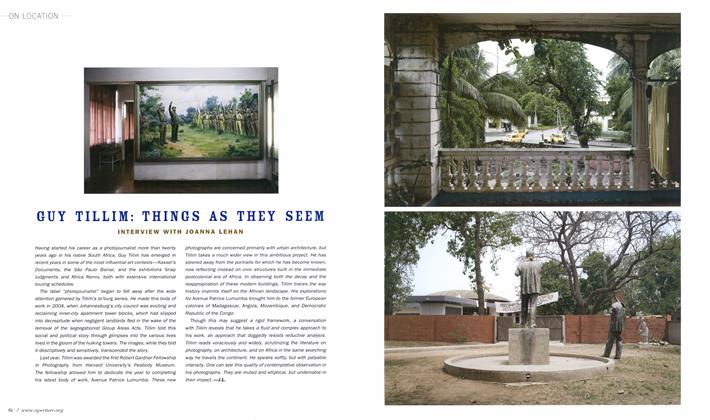

On LocationGuy Tillim: Things As They Seem

Winter 2008 By Joanna Lehan -

On Location

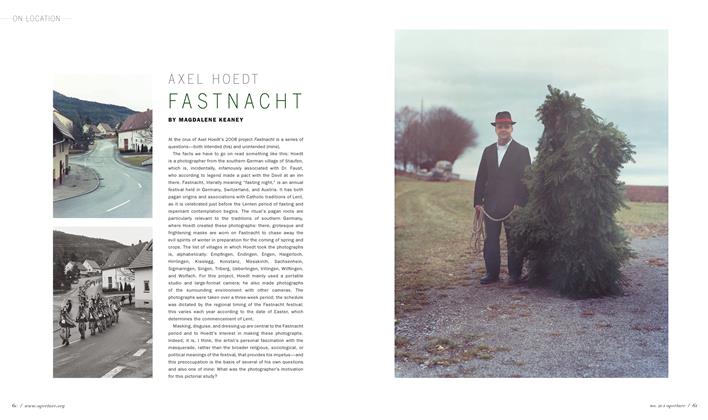

On LocationAxel Hoedt Fastnacht

Winter 2010 By Magdalene Keaney -

On Location

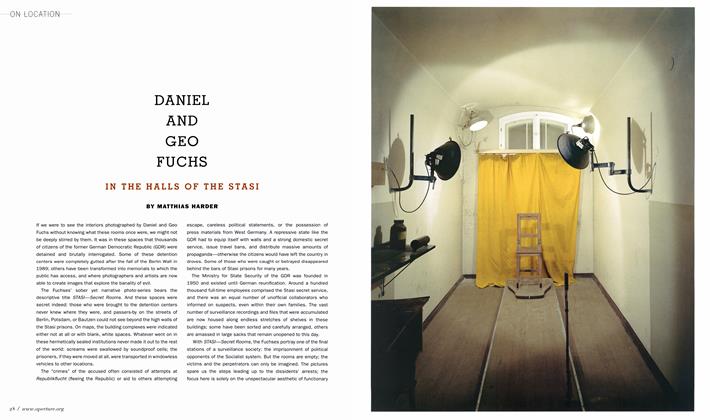

On LocationDaniel And Geo Fuchs

Summer 2009 By Matthias Harder