GERALDO DE BARROS FOTOFORMAS

WORK AND PROCESS

FERNANDO CASTRO

Brazilian artist Geraldo de Barros (1923-1998) began his engagement with photography in the late 1940s, when he was still a young man. He was by then already deeply involved in the thriving art world of São Paulo—his artistic voyage had begun when he was twenty-three, with studies in drawing and painting. In 1948 he and a group of other artists established what came to be known as the Grupo XV studio. Like the other members of Grupo XV, de Barros was a proponent of the Expressionist style, though he sought to expand his horizons and often visited Säo Paulo’s Biblioteca Municipal to look at books on such subjects as Gestalt, Paul Klee, and the Bauhaus.

De Barros became fascinated by the creative possibilities of photography. He bought a 6-by-6 twin-lens Rolleiflex camera and joined the Foto Cine Club Bandeirantes—which was, according to his biographer Michel Favre, “the only place in Säo Paulo where photography lovers would meet.”1 De Barros, who was younger than most of the other members, however, was not interested in Pictorialism, which dominated the club’s thinking. He set up a darkroom at the Grupo XV’s studio and set out to photograph places he had previously painted. Although a number of his early images are fairly orthodox, it was not long before he developed a penchant for experimenting with the medium.

De Barros’s innovative approach was rewarded in 1949 when he was asked to organize a photography laboratory at the newly founded Museu de Arte de Säo Paulo. In this same period, he embarked on a series of photographic experiments that would culminate in his 1950 solo exhibition Fotoformas at the museum. (De Barros dedicated the show to Pablo Picasso, a telling fact given the different directions his work would take.) The artist coined the term Fotoforma—the prefix “foto” acknowledging the role of light in the production of the works, and the suffix “forma” testifying to the impact Gestalt theories were already having in the Brazilian art world {Gestalt may be translated as “shape” or “form”).

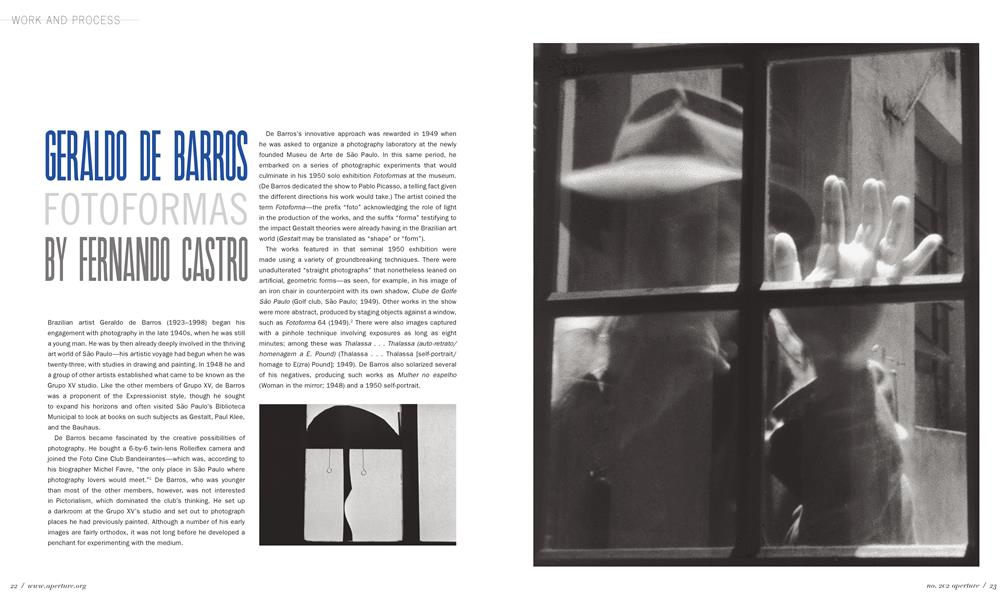

The works featured in that seminal 1950 exhibition were made using a variety of groundbreaking techniques. There were unadulterated “straight photographs” that nonetheless leaned on artificial, geometric forms—as seen, for example, in his image of an iron chair in counterpoint with its own shadow, Clube de Golfe Säo Paulo (Golf club, Säo Paulo; 1949). Other works in the show were more abstract, produced by staging objects against a window, such as Fotoforma 64 (1949).2 There were also images captured with a pinhole technique involving exposures as long as eight minutes; among these was Thalassa . . . Thalassa (auto-retrato/ homenagem a E. Pound) (Thalassa . . . Thalassa [self-portrait/ homage to E(zra) Pound]; 1949). De Barros also solarized several of his negatives, producing such works as Mulher no espelho (Woman in the mirror; 1948) and a 1950 self-portrait.

Some of de Barros’s most radically abstract works are multiple-exposure photographs he made with his Rolleiflex. A number of these closely resemble photograms—so closely, indeed, that they are easily mistaken for them (consider for example Fotoforma 96 and Fotoforma 100, both 1950). But de Barros never created photograms—and in fact, these images are really more surprising, bewildering, and intriguing as multipleexposures. The fact that these works are not purely abstract, but denotative, presented something of an inconvenience for the Concrete art agenda that de Barros would later embrace. (The Concrete art, or arte concreto, movement—which espoused the concept that abstraction should have no symbolic association with reality—had much currency in Brazil in the 1950s.) The interpretation of a photographic image does not stop with its visual appearance; there is an inevitable challenge to consider its etiology—which becomes part of its meaning. As multiple exposures, these deceptively simple abstract images pose a conundrum that demands further scrutiny.

Although manipulation of the negative does not necessarily fall outside the boundaries of traditional photographic practice, it is clear that de Barros’s intentions in altering the negatives of many of his “Expressionistic” works derive from another place. At some point the artist seems to have realized that the negative could be used as a kind of etching plate: his Homenagem a Picasso and Homenagem a Stravinsky—tributes to Picasso and Igor Stravinsky, both from 1949—were described by de Barros as “drawing[s] on the negative[s] with drypoint and ink.” He made scratches (which register as black) on developed negatives that already contained a recorded image, and then painted them (this registers as white). The eggs and bird in his Cemitério do Tatuapé (Cemetery of Tatuapé; 1949) owe their existence not to photography but to the artist’s hand. Going further, de Barros trimmed the print following the contours of the image—a technique he would deploy with several works.3

We may guess that de Barros took pleasure in creating layers of confusion: some works that appear to be products of scratched/ painted negatives—such as O barco e o baläo (Ship and balloon; 1948)—are actually straight photographs. In this image, it is not the negative but the depicted walls that are actually scratched and drawn-upon (maybe by de Barros himself, though we cannot know with certainty).

In another group of images, de Barros cut the negative and sandwiched the scraps between two pieces of glass that he placed in the negative carrier of his enlarger, producing works such as Fotoforma 92 (1949). The images de Barros produced with this technique in 1948-50 tend to be geometric and abstract and— except for slight traces of photographed textures—adhere to the paradigm of Concrete art.

Finally, there are images made by placing something other than a negative in the enlarger’s negative-carrier: a perforated computer card, for example—a technique that in 1949 produced two Fotoformas (94 and 95). To create these, the artist moved the enlarger head up and down to alter the size of the rectangular perforations on the computer card—a process that would be difficult, though not impossible, to repeat precisely. These two unique 1949 prints, which resemble monochromatic works by Piet Mondrian, were harbingers of the route photography would take fifty years later, as the medium merged digitally with cyber-technology.

Although there is little record of the response of artists and photographers to de Barros’s 1950 show at the Museu de Arte de Säo Paulo, one practical result of it was that de Barros received a grant from the French government to study printing in France. The year he subsequently spent in Europe, beginning in early 1951, led to an artistic transformation—as well as a four-decade hiatus in de Barros’s practice of art photography. He met Giorgio Morandi in Italy, François Morellet in Paris, and Otl Aicher in Ulm; it has been suggested that he also may have encountered Brassai and Henri Cartier-Bresson during this period.

In Zurich de Barros visited Max Bill, whom he had met previously in Säo Paulo. Bill—the dean of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm and one of the most outspoken apostles of Concrete art in both Europe and Brazil—unquestionably made a deep impression on de Barros. After he returned to Säo Paulo, in 1952, de Barros cofounded the Grupo Ruptura: Brazil’s very active branch of the Concrete art movement.

The overall mission of the Concretists was to move away from mere figurative depiction and embrace a truly “objective” art that represented nothing but itself. Many of them felt that the role of the artist had become overly romanticized, and defined themselves as “workers.” The Concrete artists also believed in making art accessible to all people through the creation and distribution of intelligently designed items for modern living—indeed, the Grupo Ruptura understood their vision of art as fully congruent and inherent to Brazil’s ongoing modernization. De Barros was a prominent member of the group and participated in national and international exhibitions of Concrete art.

In 1954 de Barros and a priest named Joäo Batista Pereira dos Santos established Unilabor, a worker-owned furnituremanufacturing cooperative, with a view to providing the public with well-designed furnishings. Within a decade, however, this utopian experiment was beset by financial and managerial difficulties (and after Brazil’s 1964 military coup, suspicions were inevitably cast on this socialist-style endeavor). De Barros left Unilabor and joined Aluisio Bioni in creating the privately owned Hobjeto furniture factory and chain of stores.

In the 1960s, with the advent of Pop art, de Barros returned to painting, working now in an entirely new and figurative mode. Together with fellow Brazilian artists Nelson Leirner and Wesley Duke Lee, he opened Rex Gallery in the back room of one of the Hobjeto stores. At this time de Barros’s work consisted of appropriating posters and billboards he found in the street and modifying them: painting over them and making collages with them. In Michel Favre’s documentary film on de Barros, Leirner recalls: “His concept was to bring elements from the street inside the gallery and from the inside back to the street.” While the business demands of Hobjeto deterred de Barros’s career as a Pop artist, by the 1970s the commercial success of the company enabled him to build a lofty new home with a studio and to travel extensively with his family.

In 1975 de Barros’s daughter Fabiana came across the photographic prints her father had made twenty-five years before; this rediscovery rekindled de Barros’s enthusiasm for creating art. He reestablished contact with the artistic circles of his younger years. At the same time, Brazil’s economic crisis was affecting his furniture business and de Barros found himself under increasing financial strain. In 1979 he suffered the first of several attacks of cerebral ischemia, or strokes. He was fifty-six years old.

Although physically weakened, de Barros remained fully lucid and was determined to continue working as an artist. He was still able to sketch geometric patterns, like those he had done in the 1950s when he was one of Brazil’s most renowned Concrete artists. With the help of an assistant, he managed to produce an astounding new series of abstract works, several of which were featured at the 1979 Bienal Internacional de Arte in Säo Paulo.

De Barros’s active creative mind was for some time strong enough to overpower his physical limitations, and he further radicalized his long-held idea of redefining art by using industrial materials instead of paint: in one series, Jogos de Dados (Dice games; 1983-96), he made use of Formica as a medium. De Barros’s newly created works drew such acclaim that he was invited to represent Brazil at the 1986 Venice Biennial. (“After I got sick, I got better,” he once noted wryly.) In 1988, de Barros suffered a succession of strokes and was afterward confined to a wheelchair—and yet he continued to sketch and plan new works.

Fabiana de Barros, an artist in her own right, has played a crucial role in the recognition of her father’s work. It was thanks to her efforts that in 1993 the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne brought a major exhibition of his work to Europe: Geraldo de Barros: Peintre et Photographe. Curiously, much of the renewed interest in his oeuvre focused on his photography of four decades earlier. The Fotoformas were exhibited, written about, and understood anew nearly half a century after their first showing.

De Barros was delighted with this enthusiasm for his photographic efforts. In the last two years of his life, working with an assistant, he produced 250 new photographic works. He titled the series Sobras (Leftovers) because they were made from photographs of his family and travel albums that were never destined to be anything but mementos. “A photograph,” de Barros once said, “belongs to the one who makes something out of it, not necessarily to the one who took it.”©

NOTES

1. Michel Favre, de Barros’s mostassiduous biographer, is alsothe husband of Fabiana de Barros, the artist’s daughter. Much of the information about de Barros in this essay is extracted from Favre’s “Biography of the Artist” in his book Geraldo de Barros 1923-1998: Fotoformas (Munich: Prestel, 1999) and from his documentary film Geraldo de Barros: Sobras em obras (Switzerland and Brazil: Tradam SA/Tatu Filmes Ltda., 1999). Writings by several other authors were also consulted for this article, among them Charles-Henri Favrod, Max Bill, Marcos Augusto Gonçalves, Daniel Girardin, Reinhold Misselbeck, Adon Peres, and Ana Maria Belluzo. I am also grateful to Fabiana de Barros for her invaluable feedback.

2. As de Barros created numerous pieces titled simply Fotoforma, for the readers’ reference I have numbered these works according to their page numbers in the book Fotoformas: Geraldo de Barros, Fotografías, compiled by Augusto Massi (Säo Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2006).

3. For more on de Barros’s use of this technique, particularly in his 1949 image A menina do sapato (The girl from the shoe), please follow links for “de Barros” at: http://www.zonezero.com/magazine/indexen.html).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

On Location

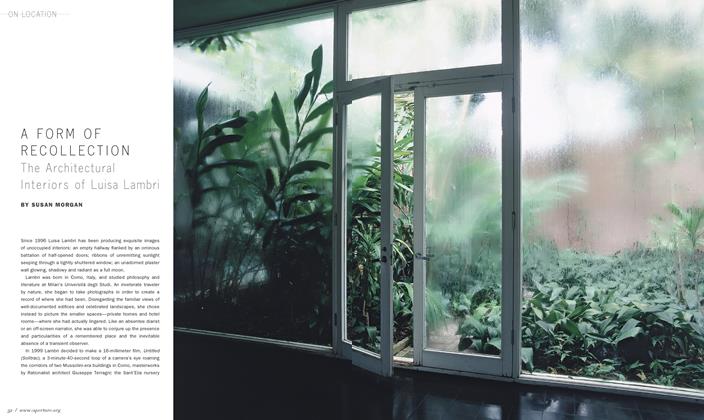

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

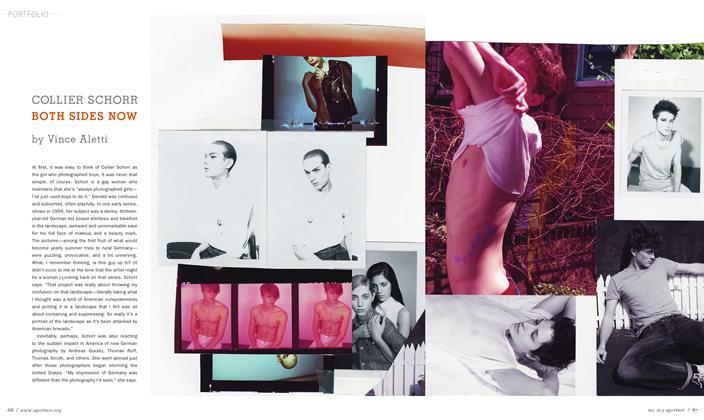

Portfolio

PortfolioCollier Schorr Both Sides Now

Spring 2011 By Vince Aletti -

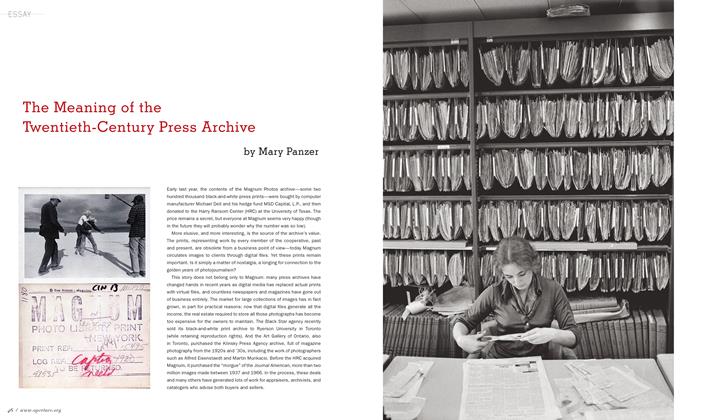

Essay

EssayThe Meaning Of The Twentieth-Century Press Archive

Spring 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaSara Vanderbeek Compositions

Spring 2011 By Brian Sholis -

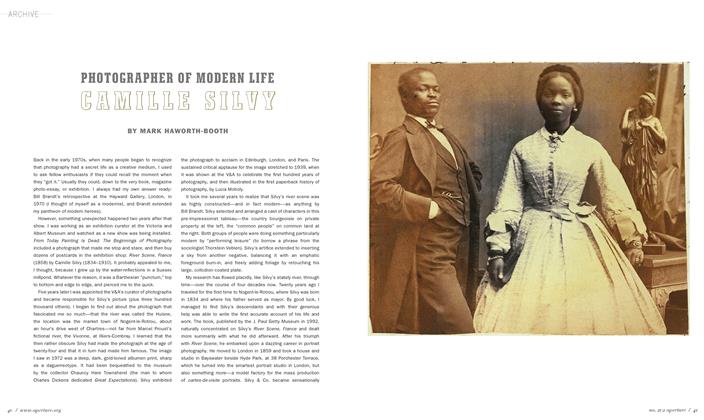

Archive

ArchivePhotographer Of Modern Life Camille Silvy

Spring 2011 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Fernando Castro

Work And Process

-

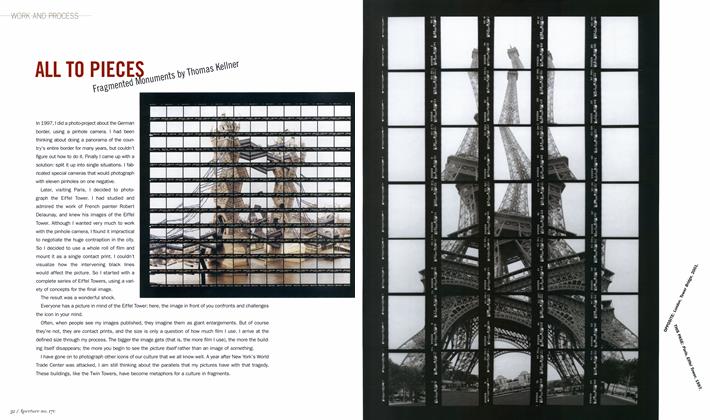

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAll To Pieces: Fragmented Monuments By Thomas Kellner

Spring 2003 -

Work And Process

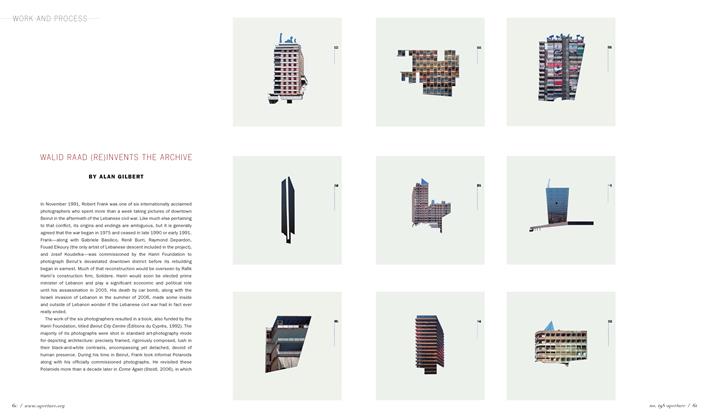

Work And ProcessWalid Raad (re)invents The Archive

Spring 2010 By Alan Gilbert -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessInstant Gratification

Spring 2001 By Arthur C. Danto -

Work And Process

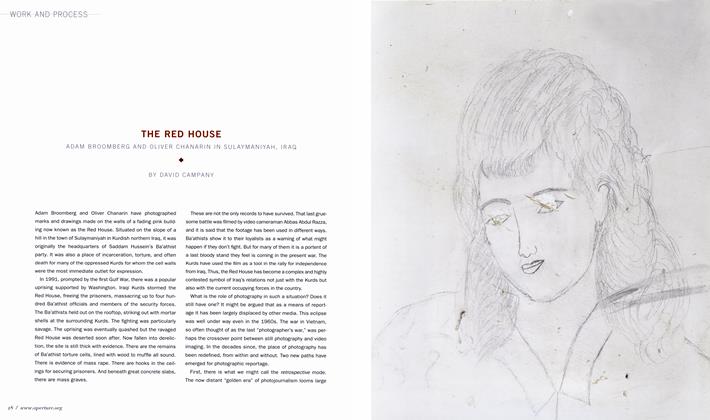

Work And ProcessThe Red House

Winter 2006 By David Campany -

Work And Process

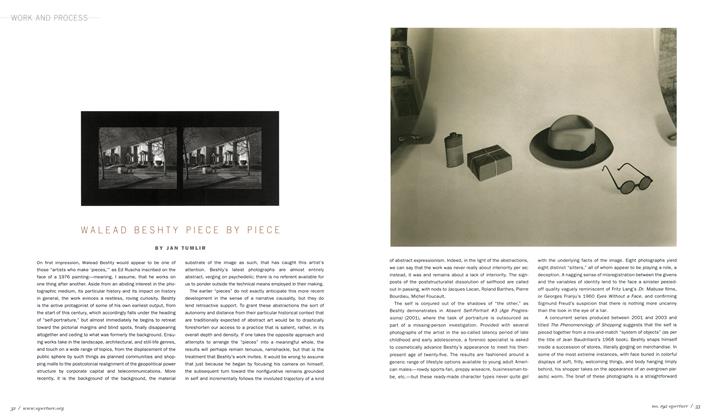

Work And ProcessWalead Beshty Piece By Piece

Fall 2008 By Jan Tumlir -

Work And Process

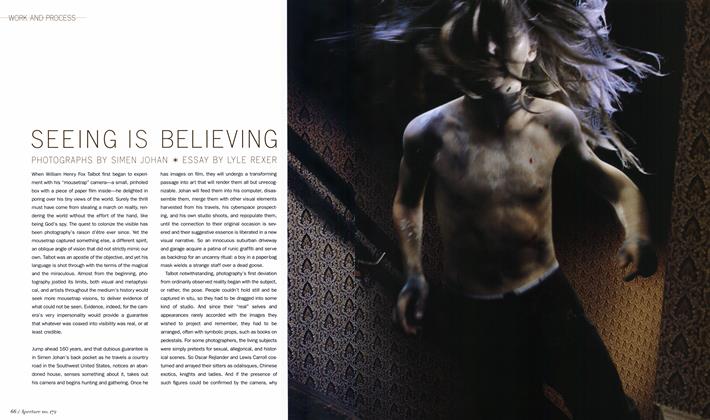

Work And ProcessSeeing Is Believing

Fall 2003 By Lyle Rexer