Words

To Walk In Both Worlds

Working within their own communities, Richard Throssel and Horace Poolaw created theatrical portraits that redefined Native American representation.

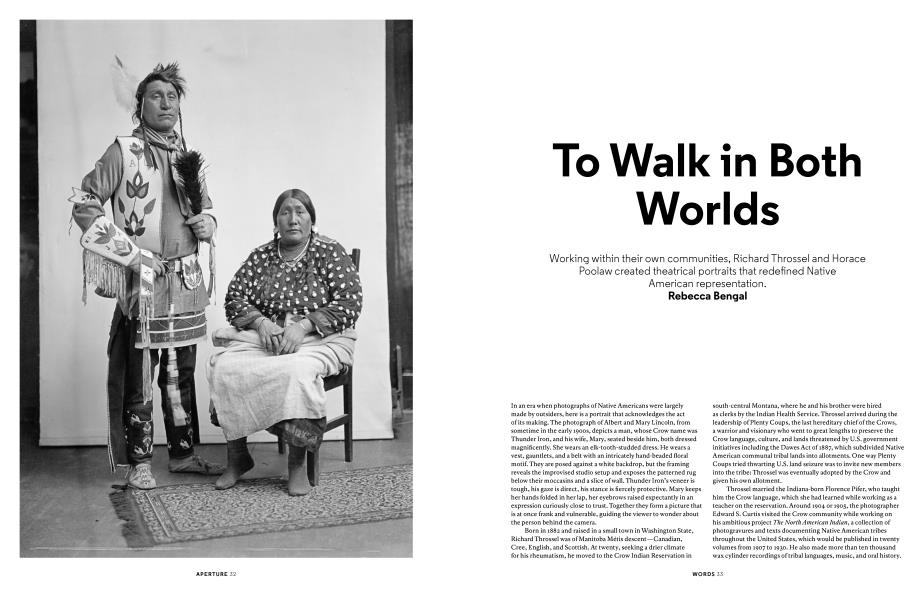

Fall 2020 Rebecca BengalIn an era when photographs of Native Americans were largely made by outsiders, here is a portrait that acknowledges the act of its making. The photograph of Albert and Mary Lincoln, from sometime in the early 1900s, depicts a man, whose Crow name was Thunder Iron, and his wife, Mary, seated beside him, both dressed magnificently. She wears an elk-tooth-studded dress. He wears a vest, gauntlets, and a belt with an intricately hand-beaded floral motif. They are posed against a white backdrop, but the framing reveals the improvised studio setup and exposes the patterned rug below their moccasins and a slice of wall. Thunder Iron’s veneer is tough, his gaze is direct, his stance is fiercely protective. Mary keeps her hands folded in her lap, her eyebrows raised expectantly in an expression curiously close to trust. Together they form a picture that is at once frank and vulnerable, guiding the viewer to wonder about the person behind the camera.

Born in 1882 and raised in a small town in Washington State, Richard Throssel was of Manitoba Metis descent—Canadian,

Cree, English, and Scottish. At twenty, seeking a drier climate for his rheumatism, he moved to the Crow Indian Reservation in south-central Montana, where he and his brother were hired as clerks by the Indian Health Service. Throssel arrived during the leadership of Plenty Coups, the last hereditary chief of the Crows, a warrior and visionary who went to great lengths to preserve the Crow language, culture, and lands threatened by U.S. government initiatives including the Dawes Act of 1887, which subdivided Native American communal tribal lands into allotments. One way Plenty Coups tried thwarting U.S. land seizure was to invite new members into the tribe: Throssel was eventually adopted by the Crow and given his own allotment.

Throssel married the Indiana-born Florence Pifer, who taught him the Crow language, which she had learned while working as a teacher on the reservation. Around 1904 or 1905, the photographer Edward S. Curtis visited the Crow community while working on his ambitious project The North American Indian, a collection of photogravures and texts documenting Native American tribes throughout the United States, which would be published in twenty volumes from 1907 to 1930. He also made more than ten thousand wax cylinder recordings of tribal languages, music, and oral history. Throssel, who had had sporadic art lessons, found Curtis’s pictures to be “a revelation”; he traveled to visit Curtis in Seattle at his studio and was inspired by him to become a photographer.

The strength of his images resides in everyday, unguarded moments that feel inherently modern.

Some of Throssel’s early photographs—Pictorialist images of riders dramatically fording rivers, or close-up portraits of heroic warriors, such as the ones he made of his friend Chief Plenty Coups—reflect the Romantic influence of Curtis’s style. In the early and mid-twentieth century, the photography of Native Americans tended to be propelled by the impetus either to promote a revisionist narrative, one of noble savages and well-meaning colonists, or to preserve the cultures colonists had aided in destroying. Curtis’s project, bankrolled by J. P. Morgan, was a white photographer’s attempt to document the “vanishing Indian” before he (women were less visible in Curtis’s work) disappeared altogether. This meant there was no time to spare. Curtis traveled incessantly, relying on local assistants to do the groundwork and interviews with the people he photographed. By contrast, being part Cree and living among the Crow community, Throssel forged deeper, long-term connections. Members of the Northern Cheyenne tribe in southeastern Montana allowed him to photograph sacred ceremonies: in those images, elaborately masked dancers move through fields as part of the Massaum, or Animal Dance, a multiday dance that honored the healing relationships between animals and humans. Throssel’s pictures are astonishingly surreal and dreamlike, the unique perspective of a near insider. They were so good that Curtis included a selection of them in the third book of his multivolume project.

But the work for which Throssel is most remembered occupies a more conflicted place between the white and Native American worlds. In 1909, he began producing several hundred plate-glass negatives, lantern slides, and a dozen moving pictures as part of a traveling government-run health campaign, led by Dr. Ferdinand Shoemaker of the Office of Indian Affairs, aimed at tampering twin outbreaks of tuberculosis and trachoma in “Indian” country. Shoemaker showed Throssel’s images in well-attended lectures he gave to tribal communities all over the country. As the scholar Rebecca S. Wingo wrote, “It was a traveling lecture that left cultural devastation in its wake.” Irony was unconsciously laced into these images; early colonists brought devastating disease to Native Americans and now the government was attempting to discourage traditional practices, such as sitting on the ground to eat, in the name of health. For one of the images meant to “correct” these behaviors, Interior of the Best Indian Kitchen on the Crow Reservation (1910), Throssel photographed a Crow family at a Euro-American-style dinner table. The elk tooth and beaded clothing of the mother and father contrasts with the china settings and strikingly patterned wallpaper.

“If the family were well-off agency employees themselves, it’s possible they were in their own home,” suggests Timothy McCleary, a professor at Little Big Horn College in Montana. “But even so, they wouldn’t have worn their best clothes to an everyday dinner.” Such styling lends a performative aspect to the photograph, casting the family as actors in an assimilation narrative, with subliminal suggestions of house and dress. Not only was this the way to eat, this was the way to live. Throssel, who received little credit for the work he did for this campaign, left the job out of frustration in 1911. He spent the last two decades of his life operating a commercial studio in Billings, Montana, returning to Crow lands to photograph the communities there, and served two terms as a state legislator, during which he advocated for Native American causes.

Although Throssel never became widely known in his lifetime, the scholar Peggy Albright’s 1997 biography, Crow Indian Photographer: The Work of Richard Throssel, helped bring his pictures belatedly to light. And in 2003, the National Museum of the American Indian in New York held the exhibition Telling a Crow Story: The Photographs of Richard Throssel, seventy years after his sudden death in 1933. On the Crow Indian Reservation, Throssel’s legacy has endured for decades through the studio portraits and candid pictures he made of women and children. The strength of his images resides in everyday, unguarded moments that feel inherently modern, freed from the dominant narrative of the “vanishing Indian” advanced by Curtis’s vision. “Whether they were aware of the photographer’s name or not, a lot of Crow people have been living with Throssel’s pictures in their homes and in the community for years,” says McCleary. “They become family treasures.”

Horace Poolaw, born in 1906, and working almost a full generation after Throssel, expressed similar hopes for his own legacy of photographing his Kiowa community in and around Anadarko, Oklahoma. “I don’t want to be remembered through my pictures;

I want my people to remember themselves,” Poolaw once said. It was a natural way of thinking for the son of a prominent local historian. His father, known as Kiowa George, was one of the keepers of the tribe’s calendar—the pictographic record of the community’s life, including notable events, ceremonies, births, and deaths.

At the core of the body of work Poolaw left behind at his death in 1984 are family and community pictures: his baby son Bryce, diapered and grinning on a sofa perched between his sister’s two Anglo-looking baby dolls; his children Linda and Robert dressed as a cowgirl and a cowboy with toy guns. At regional Indian fairs and expositions and parades, Poolaw photographed veterans in procession and Kiowa beauty queens atop slicked-up convertibles. He photographed his son Jerry in his Navy years in a crackerjack uniform and a warbonnet. Poolaw also photographed Jerry at age five or six, in 1929, dressed in a tweed suit and hat. Tom Jones, cocurator of For a Love of His People: The Photography of Horace Poolaw, an exhibition organized in 2014 by the National Museum of the American Indian, rightly compares this image of Poolaw’s to a portrait by August Sander.

Despite its undeniable power, Poolaw’s work was not widely known outside his community for decades. “Whoever heard of an Indian who took Indian pictures?” his daughter Linda Poolaw said to me, half-jokingly, while speaking by phone from her home in Anadarko. In 1989, in cooperation with Stanford University, Linda codirected the Horace Poolaw Photography Project, which organized, printed, and archived some two thousand of her father’s large-format negatives and launched a traveling exhibition. Although she maintains her father never intended to photograph “Kiowas in transition,” his work is frequently understood as a document of the community’s passage into midcentury American life. Poolaw’s most productive years as a photographer overlapped with the two World Wars, the Great Depression, the rise of the automobile as an everyday fixture, and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Indian New Deal,” which aimed to reverse the forced cultural assimilation of Native Americans. Poolaw was born in a tipi and later moved into a modern house; his classmates at the largely white public school in Mountain View, Oklahoma, recall watching him and his brothers hitching up their horses before classes and galloping away after the last bell in a cloud of dust. He left school after the sixth grade and later apprenticed himself to two photographers who came through Oklahoma on the newly connected Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific railroad lines.

He raised cattle, worked as a highway patrolman, and joined the Army Air Corps in his late thirties, teaching aerial photography at MacDill Field in Tampa, Florida. A critic, writing about his work in 1992, described Poolaw as “a witness to the tragic passing of the Kiowa world,” a sentiment that reinforces the “vanishing Indian” trope of Throssel’s era but sorely misses the spirit of these startlingly modern, at times ironic pictures, which transmit a sense of unfiltered joy.

“Out in the world, he was everybody’s friend,” Linda remembers. “We’d go to town and it was all ‘Hi, Horace,’ ‘Hi, Horace.’ He liked white people, Black people, Indian people, Mexican people, everybody.” At home, Poolaw was strict and private. A stalwart Democrat, he read three newspapers a day; he disappeared into his un-air-conditioned darkroom for hours. “He didn’t share that part of his life with us,” Linda recalls, and even when her mother got a good job with the Riverside Indian School, he couldn’t afford to print most of his pictures. “I think he was afraid to show them to people,” she says. The first closest thing Poolaw had to an exhibition was over Christmas break in 1989, when a group of Stanford students spread his prints over cafeteria tables in a tribal building in Oklahoma and asked members of the Kiowa community to help identify the people in them. Some cried, recognizing their relatives. At the culmination of printing and archiving in California, Linda drove her pickup truck to the beach and sat looking at the waves. It had been a year in which her father had become famous, as a result of the Stanford project, and compared to the greatest photographers of his time; a traveling exhibition would follow, and a portfolio in a 1995 issue of this magazine. “I said to myself, I hope he’s not pissed off that I’m doing all this!” she told me.

These pictures upend the colonial narrative and image record.

Poolaw taped pages torn from Life magazine outside his darkroom door. Today, it is difficult not to consider how his story might be different had his work been seen alongside that of his contemporaries who documented the social landscape of 1930s America for the Farm Security Administration. But unlike Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, Poolaw did not focus on pictures of poverty, even when times were lean for his own family. Once, Linda asked her father why he photographed so many funerals. “Because everyone’s all dressed up!” he said. Poolaw’s grandson, John Poolaw, wrote in a text accompanying the 2014 exhibition that as a kid he was startled to come across a photograph by his grandfather that depicted his great-uncle Bruce and other family members dressed up in sharp suits, leaning against a shiny car. The image stood in stark contrast to the “sad and stiff” historical portrayals of Indians he was used to seeing: “I remember thinking that this photo should be titled ‘fancy’ because everything I saw in the photo exemplified what ‘fancy’ meant to me.”

For a time Poolaw sold (and, more often, gave away) postcards printed with his images to tourists at bus stations and fairs. Stamped on the reverse of each was this imprint: “A Poolaw Photo, Pictures by an Indian, Horace M. Poolaw, Anadarko, Okla.” While he proudly acknowledged his heritage, Poolaw also understood what it might signify to a potential non-Native buyer. His photographs of dances and parades tend to be made so closely that they deliver the feeling of being one of the participants. Occasionally, like Throssel, he pulls back to show the wider context for these events: a lineup of white tourists aiming their cameras at Kiowa dancers. Also, like Throssel, he was given permission to photograph certain ceremonies and moments normally off-limits to documentarians and tourists.

In an image of a Peyote meeting, from around 1929, participants are lying on the ground outside a tipi, many turning their faces away from the camera. Among those standing is Lucy Nicolar, a Penobscot performer known by her stage name Princess Watahwaso, who would marry Poolaw’s brother Bruce.

When she visited Oklahoma in the late 1920s, Princess Watahwaso helped usher in a new dimension to Poolaw’s practice. Raised partly in Boston by a Harvard professor, she was a mezzosoprano who made early records for the Victor Record Company and worked as an entertainer in New York and for traveling shows; Bruce Poolaw had also joined the vaudeville circuit. No one in Anadarko had seen a woman like this, a glamorous, unconventional figure who rolled into town wearing jodhpurs and riding boots and smoking a cigar. The scholar Bunny McBride has written about how Princess Watahwaso knew how to play the “exotic Indian” while also challenging the expectations of her white audiences. Princess Watahwaso introduced the idea of staging to Poolaw, suggesting that more people might respond to his work if he took inspiration from popular films and vaudeville shows.

The element of performance in Poolaw’s photographs allowed his subjects to have some control over their own images. They could show themselves as they felt they were or as they wanted to be seen. This is true of his field portraits of dancers wearing full regalia in ceremonies, or of couples donning their Western Sunday best. There are multiple photographs of his brother Bruce hamming it up in cowboy costumes and warbonnets, knowingly playing on the stereotypes he and Princess Watahwaso had learned to perform for white audiences who expected their own idea of Native authenticity. These pictures upend the colonial narrative and image record.

The Indian did not vanish, but she could cut off her braids if she so desired. The warrior could ride a horse and a brand-new car.

Poolaw’s photographs are revolutionary in their joyfulness and subversive in their embrace of change. In one of his masterful double portraits from around 1930, two Kiowa women stand in front of a tipi in near-identical, long-fringed leather dresses and beaded necklaces. The elder wears her hair in braids; the younger, radically bobbed like Clara Bow, whose style was then being imitated all over the country. Poolaw’s camera doesn’t privilege the past over the present; it celebrates each equally. Photographs of his son in a Navy uniform and headdress—or of himself and a military gunner in their headdresses and flight suits playfully posing inside a B-17—seem to say, I’m wearing a warbonnet like the one my ancestors wore as they fought the country I’m now defending. Unlike you, I have the right to wear both uniforms. Unlike you, I can walk in both worlds.

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

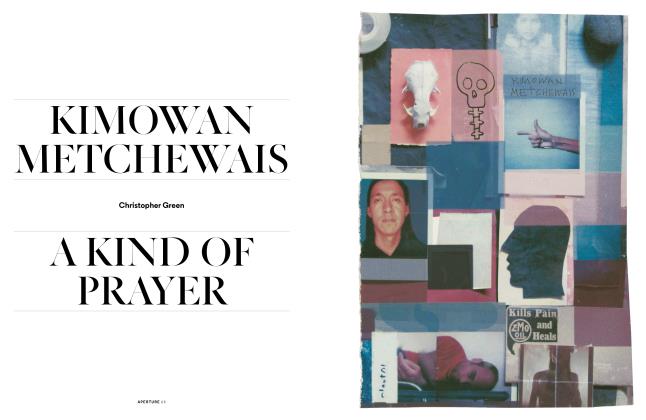

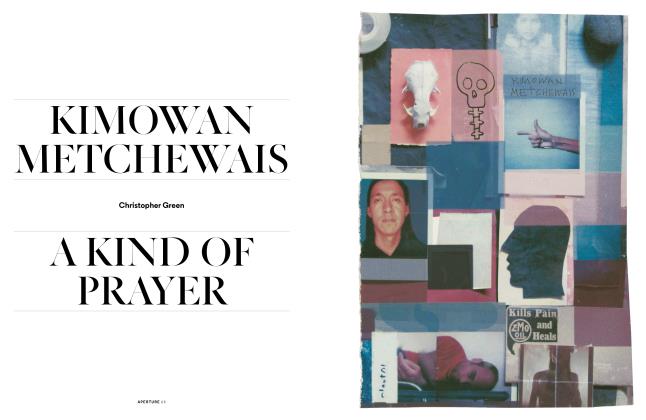

WordsKimowan Metchewais: A Kind Of Prayer

Fall 2020 By Christopher Green -

Words

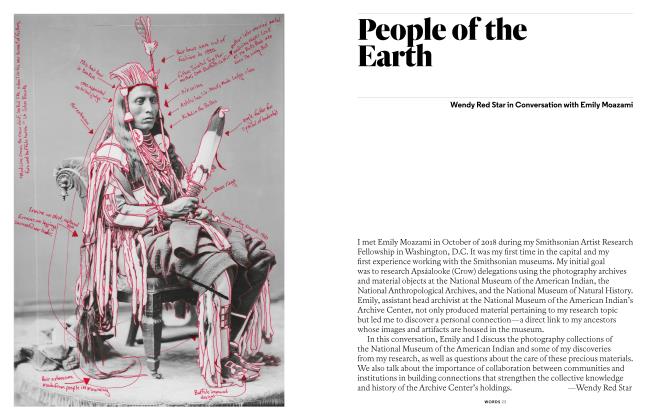

WordsPeople Of The Earth

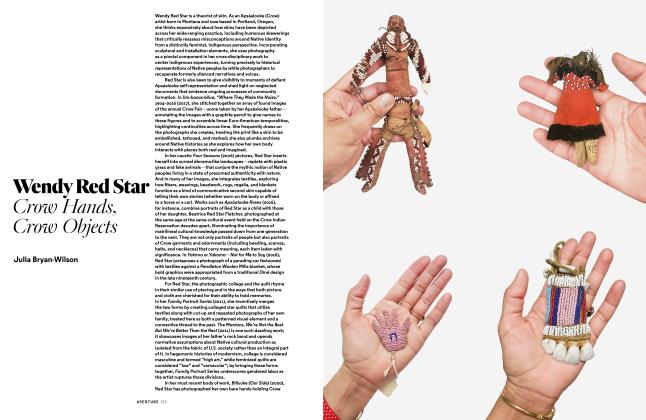

Fall 2020 By Wendy Red Star -

Words

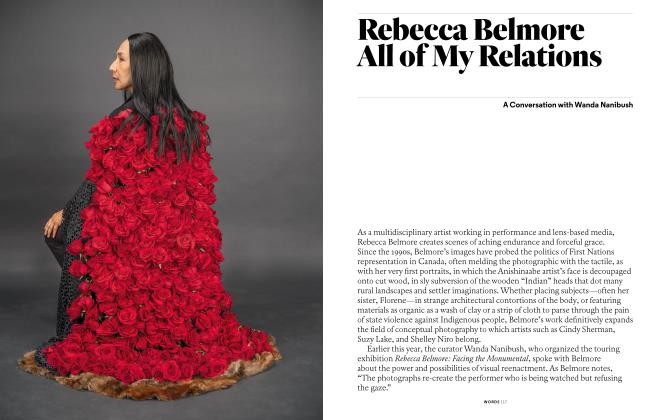

WordsRebecca Belmore: All Of My Relations

Fall 2020 By Wanda Nanibush -

Pictures

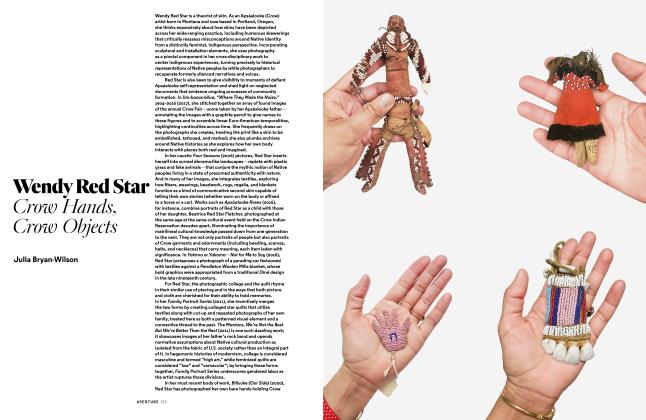

PicturesWendy Red Star

Fall 2020 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Pictures

PicturesGuadalupe Maravilla

Fall 2020 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

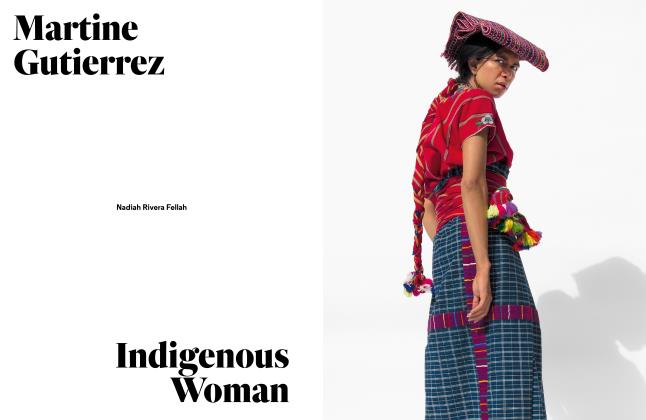

PicturesMartine Gutierrez: Indigenous Woman

Fall 2020 By Nadiah Rivera Fellah

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Native America

-

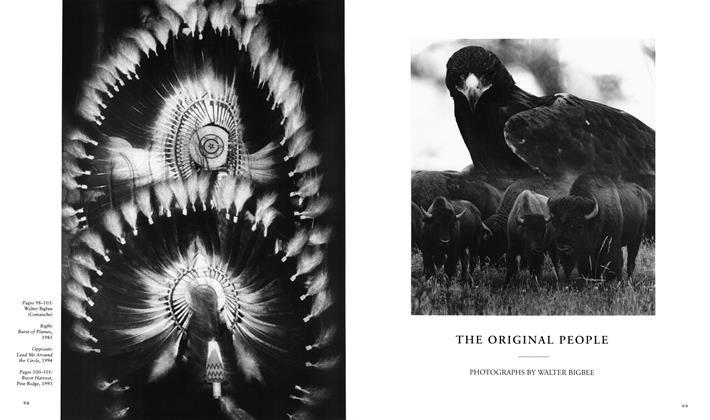

Pictures

PicturesThe Original People

Summer 1995 -

Words

WordsKimowan Metchewais: A Kind Of Prayer

Fall 2020 By Christopher Green -

Words

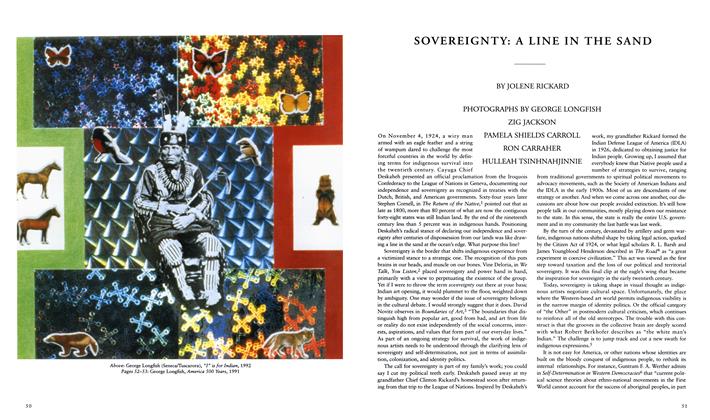

WordsSovereignty: A Line In The Sand

Summer 1995 By Jolene Rickard -

Text And Photographs

Summer 1972 By Joseph Epes Brown -

Pictures

PicturesWendy Red Star

Fall 2020 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Words

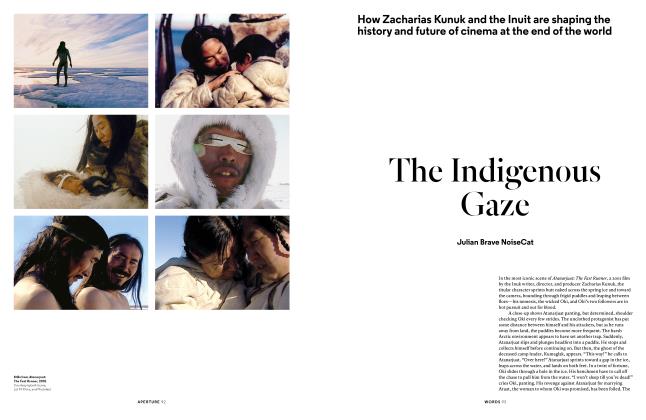

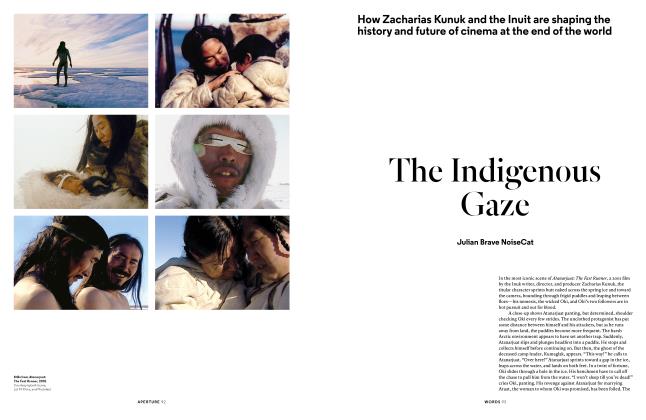

WordsThe Indigenous Gaze

Fall 2020 By Julian Brave Noisecat

Rebecca Bengal

-

Words

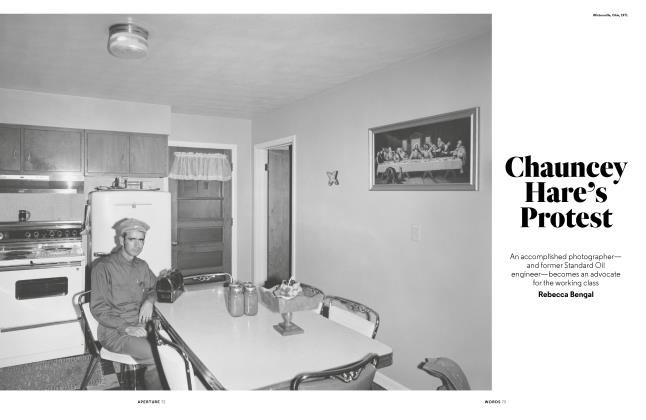

WordsChauncey Hare’s Protest

Spring 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Spotlight

SpotlightNatalie Krick

Winter 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

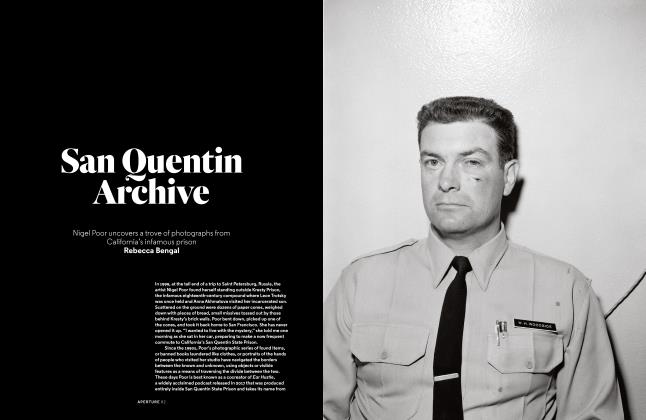

PicturesSan Quentin Archive

Spring 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesAlex Prager

Summer 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Front

FrontDay Jobs

Summer 2021 By Rebecca Bengal -

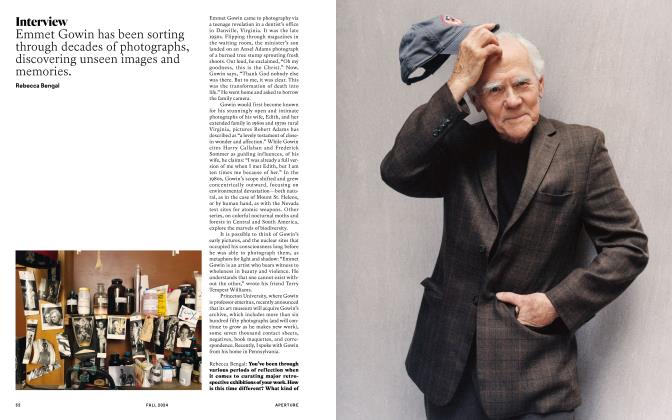

Interview

FALL 2024 By Rebecca Bengal

Words

-

Words

WordsHigher Ground

Spring 2016 By Alexander Stille -

Words

WordsAt Least They'll See The Black

Summer 2018 By Antwaun Sargent -

Words

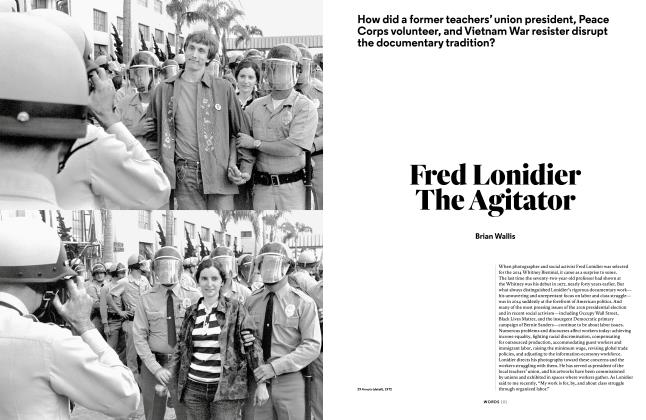

WordsFred Lonidier: The Agitator

Spring 2017 By Brian Wallis -

Words

WordsThe Indigenous Gaze

Fall 2020 By Julian Brave Noisecat -

Words

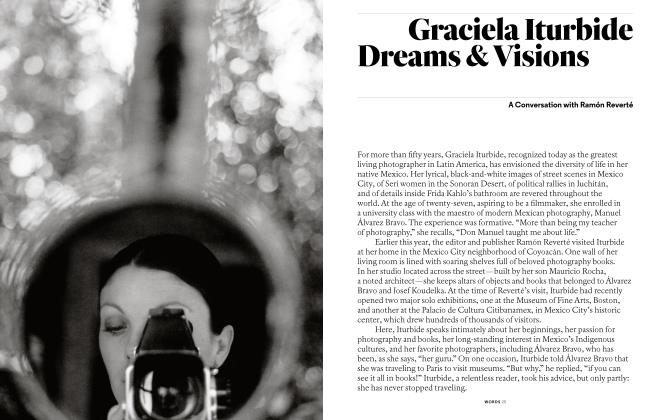

WordsGraciela Iturbide: Dreams & Visions

Fall 2019 By Ramón Reverté -

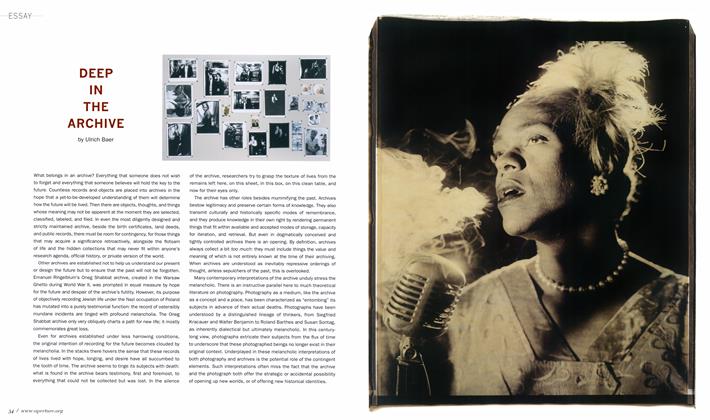

Essay

EssayDeep In The Archive

Winter 2008 By Ulrich Baer