Lovers’ Discourse

Philip Gefter

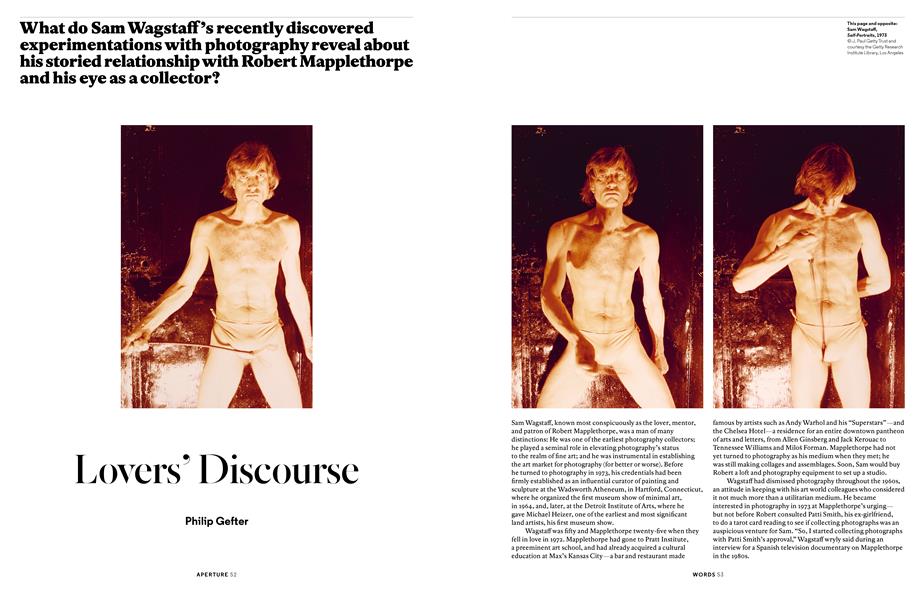

What do Sam Wagstaff's recently discovered experimentations with photography reveal about his storied relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe and his eye as a collector?

Sam Wagstaff, known most conspicuously as the lover, mentor, and patron of Robert Mapplethorpe, was a man of many distinctions: He was one of the earliest photography collectors; he played a seminal role in elevating photography’s status to the realm of fine art; and he was instrumental in establishing the art market for photography (for better or worse). Before he turned to photography in 1973, his credentials had been firmly established as an influential curator of painting and sculpture at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut, where he organized the first museum show of minimal art, in 1964, and, later, at the Detroit Institute of Arts, where he gave Michael Heizer, one of the earliest and most significant land artists, his first museum show.

Wagstaff was fifty and Mapplethorpe twenty-five when they fell in love in 1972. Mapplethorpe had gone to Pratt Institute, a preeminent art school, and had already acquired a cultural education at Max’s Kansas City—a bar and restaurant made

famous by artists such as Andy Warhol and his “Superstars”—and the Chelsea Hotel—a residence for an entire downtown pantheon of arts and letters, from Allen Ginsberg and lack Kerouac to Tennessee Williams and Milos Forman. Mapplethorpe had not yet turned to photography as his medium when they met; he was still making collages and assemblages. Soon, Sam would buy Robert a loft and photography equipment to set up a studio.

Wagstaffhad dismissed photography throughout the 1960s, an attitude in keeping with his art world colleagues who considered it not much more than a utilitarian medium. He became interested in photography in 1973 at Mapplethorpe’s urging— but not before Robert consulted Patti Smith, his ex-girlfriend, to do a tarot card reading to see if collecting photographs was an auspicious venture for Sam. “So, I started collecting photographs with Patti Smith’s approval,” Wagstaff wryly said during an interview for a Spanish television documentary on Mapplethorpe in the 1980s.

The Wagstaff papers reside at the Getty Research Institute, and during my research there for his biography, I came upon a great many photographs Wagstaff himself had taken—albeit on the down low. (Sam purchased a Leica in 1971 at the suggestion of a young photographer named Enrico Natali, who taught him how to use it.) As he began to collect photography, he started experimenting with being a photographer. This revelation adds a new dimension to the ongoing creative dialogue between patron (Wagstaff) and artist (Mapplethorpe); at the same time, it gives us additional insight into the eye of the influential collector as he was teaching himself the language of photography.

Mapplethorpe adamantly protested Wagstaff’s experimentation with the camera, a cause of great friction between them.

“I’m the artist,” he would say, according to Patricia Morrisroe’s 1995 biography of the photographer. “You’re the collector.” Still, the connection between Wagstaff’s experimentation—not only with the male figure but also with flowers—and Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre is significant. Wagstaff’s pictures, made roughly between 1973 and 1975, around the same time Mapplethorpe turned to photography as his exclusive medium, present something of a visual template for what would become signatures in Mapplethorpe’s work. That said, it is important to emphasize that neither Sam nor Robert were literally following one another’s lead or replicating each other’s ideas. Mapplethorpe was making his own original art and Wagstaff was experimenting, as if turning his art historical eye and refined sensibility to an entirely new medium. By nature of their relationship, the influence of one on the other was simply organic and fluid.

In one body of Wagstaff’s photographs, a variety of young men slowly stripped for him—over the course of an hour or an afternoon—either in his New York City apartment or at his Fire Island beach house. It is clear from the informality of the sittings and the evident playfulness between photographer and subject that Wagstaff knew these men, capturing them in varying degrees of familiarity. Despite the intimate eroticism, Wagstaff aspired to universalize the male nude—that is, to render it in keeping with classical sculpture. This is most apparent in the albums he assembled of his own prints, in which he juxtaposed pictures of the naked body—the isolated torso, the shoulder, the buttocks, genitalia—with his pictures of the sculpted figure in museums throughout Europe. He seemed to be aiming for studies of the male nude figure for the ages.

Wagstaff’s pictures, made roughly between 1973 and 1975» around the same time Mapplethorpe turned to photography as his exclusive medium, present something of a visual template for what would become signatures in Mapplethorpe’s work.

Wagstaff was experimenting with photography in the historic period following the Stonewall Riots of 1969, which occurred not very far from his own downtown loft, and the presence of a gay community had become both visible and palpable. His interest in taking photographs was also concurrent with the moment in his own life when he could be more open about his sexuality. Mapplethorpe, who came of age in that new era of gay liberation, was much freer about his attraction to men: “Sam really respected the way I was honest about being gay,” Robert told his biographer. I helped Sam to be more open about his sexuality.”

While Sam’s pictures manifest serious visual examination of his subject matter, equally they are expressive of his own homosexual desire. In his self-portraits, he used the camera as if it were a mirror in which to examine his newly liberated gay male identity; he photographed himself not as a fifty-year-old man but rather as a post-adolescent trying new ways of appearing sexy. At the same time he experimented with the formal characteristics of the mirror image, photographing an unknown model alongside the model’s mirrored reflection, thereby representing two figures in the same image; he also photographed two models repeating the same gesture, as if to emulate a mirror reflection. This visual pattern of inquiry explores the perceptual ambiguities in the photographic image, but perhaps in metaphor as well, the double life he must have experienced as a closeted gay man before Stonewall, and before meeting Mapplethorpe.

Wagstaff also played with the juxtaposition of multiple images. In one vertical triptych, a disembodied hand in the top frame reaches toward the naked male torso in the frames below. The hand, outstretched yet isolated and contained, effectively evokes longing, and the nude figure afloat in the water, facedown, with legs extended from the second to the third frame, represents an object of desire outside of the hand’s reach. This triptych is in keeping with the conceptual work—collage and assemblage—Wagstaff was familiar with in the 1960s; Mapplethorpe, too, was working in that vein when he and Wagstaff first met, before turning solely to photography.

In some pictures, the human figure appears in a frame within a frame. In Figure with Sheet (ca. 1973), for example, the male subject stands naked in front of a blue sheet, holding it taut with his hands on top and his feet at the bottom. While the photograph simulates—as well as makes vertical—the gesture of lying on a bed, the sheet serves as an improvisational device to establish a frame within the borders of the image. The figure is abstracted against—and contained within—a solid color. Because of Wagstaff’s formal art historical training, he would have known Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, a drawing in which a male nude figure, contained within a circle, stretches his arms and his legs out as if to create the shape of the letter X as he touches four points within the perimeter. Mapplethorpe, too, situated the male nude in a similar manner. In Thomas (1986), his own version of Vitruvian Man, an African-American male nude is framed within a white square box, his outstretched hands and feet firmly planted at all four corners.

In both the Mapplethorpe and Wagstaff photographs, a male nude stands head to toe inside a frame within a frame; in both photographs, the corners of the interior frames are punctuated with the figures’ extremities. At the same time, the differences are poignant in terms of meaning, intention, and resolution: Wagstaff’s nude is a playful color photograph taken outdoors in a casual setting. His Caucasian subject, looking directly into the camera, is poised to determine his own fate; his hands and feet control the blue sheet in which he is framed, and he is free to step out of it at any moment.

By contrast, the highly formalized perfection of Mapplethorpe’s black-and-white photograph, made in the studio, distinguishes it immediately as a Mapplethorpe. The figure’s gesture of determination suggests that he is pushing against the walls of the box, as if trapped. The geometry of the man-made square is emphasized by the architecture of the male form. The subject’s hanging genitalia at the very center of the photograph suggests the weight of an anchor in the lapidary composition.

Flowers were another ofWagstaff’s occasional visual preoccupations: “Was amused to hear you’ve been doing flowers (because I have, too),” Sam wrote in one letter to Robert around 1975, who was away in London, tempting the fates by hinting at his own forays with the camera; but, deftly, he quickly turned the subject back to his passion for Mapplethorpe’s work: “I’m looking forward to seeing them because anything you do has for me a very exquisite precision and a rare point of view of love from an unusual angle.” Several years later, in 1978 Wagstaff would put a Mapplethorpe diptych of a spray of tulips on the cover of Book of Photographs from the Collection of Sam Wagstaff. That book cover was Wagstaff’s way of placing Mapplethorpe in a continuum in the history of photography—from Thomas Eakins to Charles Aubry, Nadar, Wilhelm von Gloeden,

August Sander, and many others—represented inside the book, and another strategy to elevate Mapplethorpe’s stature, since he did not yet have a foothold in the art world.

Some have concluded that Mapplethorpe was Wagstaff’s creation, and there is no doubt that Wagstaff’s art world pedigree, his patrician background, his financial support, and his predisposition to encourage young artists gave the young Mapplethorpe an exceptional advantage at the beginning of his career. Yet, Mapplethorpe, in his own right, was always an artist of serious talent, ambition, and originality.

My purpose here is not to discount Mapplethorpe’s noteworthy accomplishment as an artist but to call attention to the visual dialogue that took place in their association, evident in the discovery of Wagstaff’s own brief photographic output. Wagstaff’s photographs illuminate the relationship of patron to artist as much as the lovers’ discourse. And, in art historical terms, the interaction between their respective photographs underscores the burgeoning interest in photography as a fine art in the 1970s and its confluence with the birth of the gay rights movement. That historic coincidence shaped Mapplethorpe, just as Mapplethorpe’s work symbolizes that very confluence.

At the same time, an understanding ofWagstaff’s own critical and curatorial eye is brought forward in the photographs he was making: Not only do his pictures anatomize the aesthetic with which he assembled a world-class photography collection, they chart his own artistic experimentation as it affected—and was affected by—the history of the medium. The influence of Eugène Atget, for example, can be seen in the way Wagstaff photographed the staircase in his loft building—as if it were taken in Paris at the turn of the century. He photographed patterns of shadows from a height above the street in the same way Germaine Krull photographed the filigreed shadows of the Eiffel Tower from above. In effect, his eye was educated by the history of photography as he discovered it; he emulated the different photographers he was discovering, perhaps as a way of understanding the language of photography. The dialogue between Wagstaff’s own experimental images and the work of his young lover is certainly relevant to a further understanding of Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre. But the dialogue between Wagstaff’s pictures and the vast collection he assembled across the history of photography is of equal importance.

Philip Gefter is the author of the biography Wagstaff: Before and After Mapplethorpe (2014) and the essay collection Photography After Frank, published by Aperture in 2009. He produced the 2010 documentary film Bill Cunningham New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

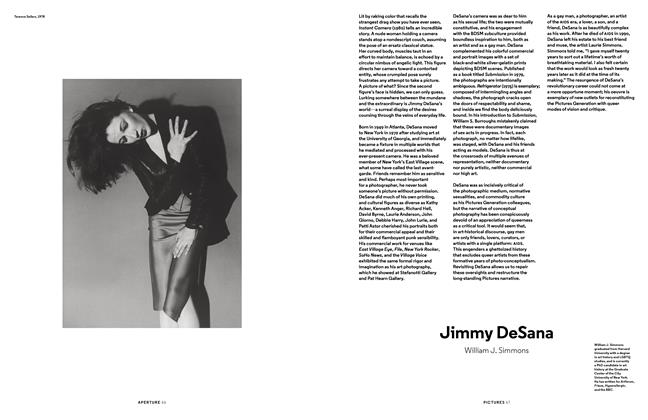

PicturesJimmy DeSana

Spring 2015 By William J. Simmons -

Pictures

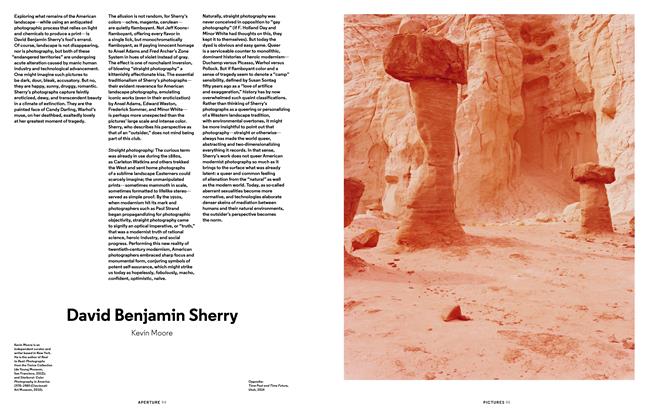

PicturesDavid Benjamin Sherry

Spring 2015 By Kevin Moore -

Pictures

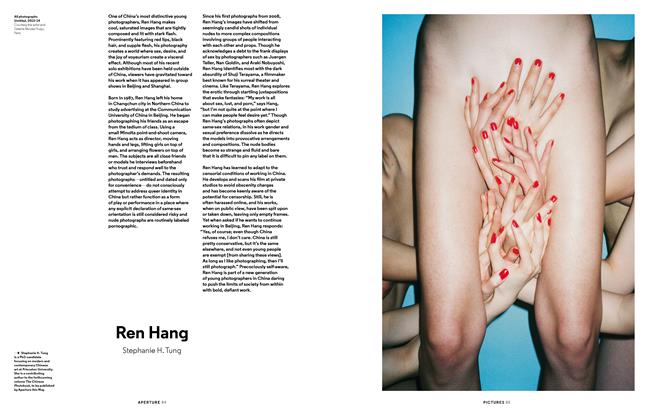

PicturesRen Hang

Spring 2015 By Stephanie H. Tung -

Words

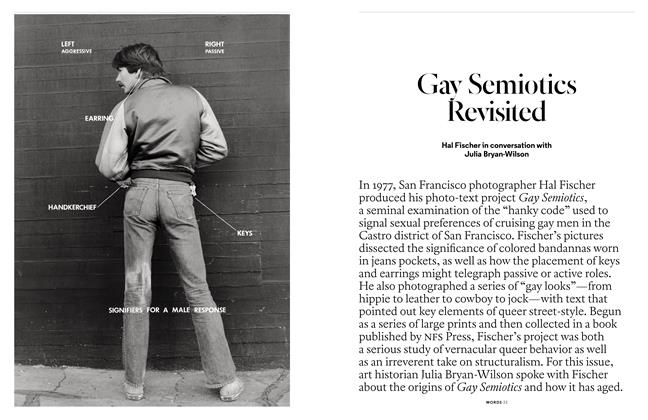

WordsGay Semiotics Revisited

Spring 2015 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Pictures

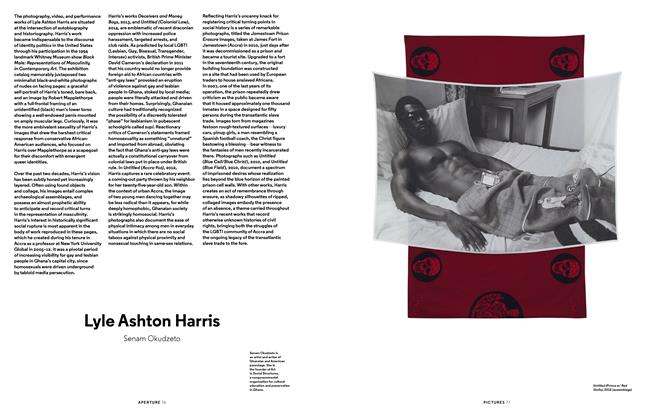

PicturesLyle Ashton Harris

Spring 2015 By Senam Okudzeto -

Pictures

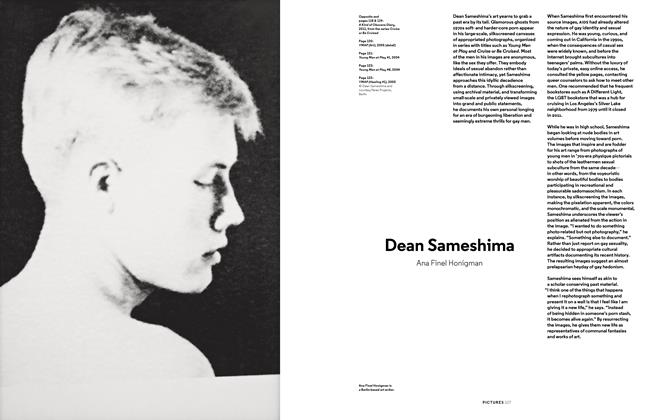

PicturesDean Sameshima

Spring 2015 By Ana Finel Honigman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Philip Gefter

-

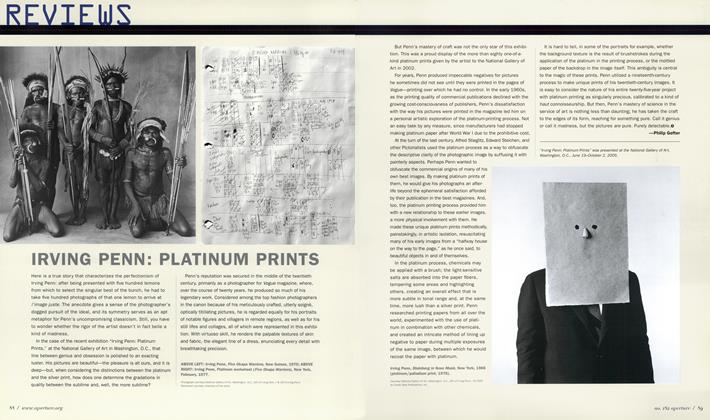

Reviews

ReviewsIrving Penn: Platinum Prints

Spring 2006 By Philip Gefter -

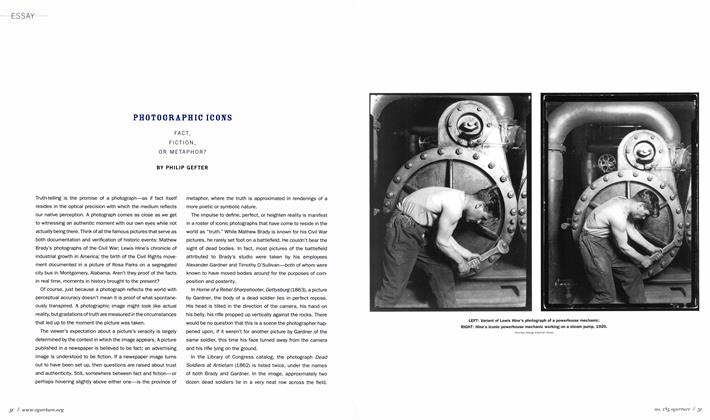

Essay

EssayPhotographic Icons

Winter 2006 By Philip Gefter -

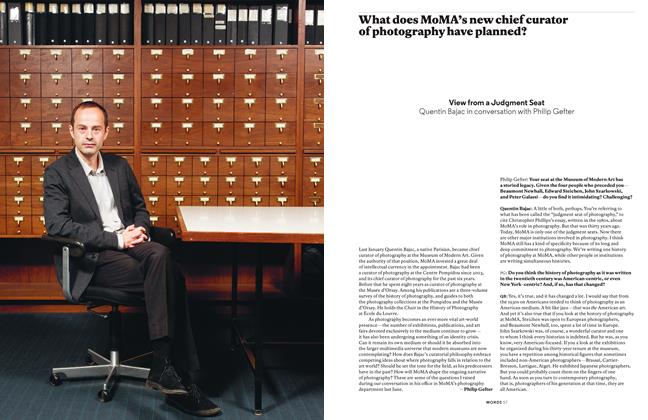

Words

WordsView From A Judgment Seat

Winter 2013 By Philip Gefter -

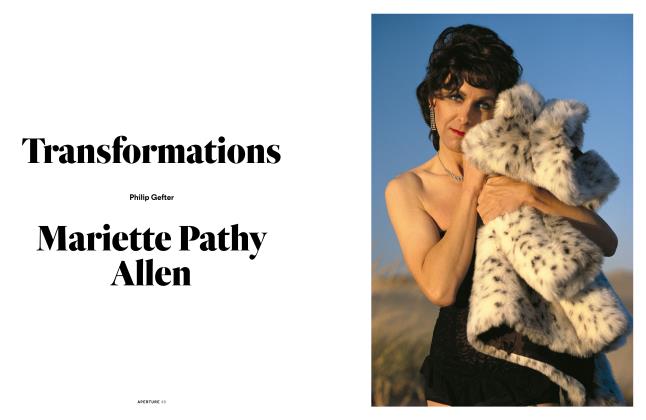

Pictures

PicturesTransformations: Mariette Pathy Allen

Winter 2017 By Philip Gefter -

Words

WordsSofia Coppola On Pictures

Summer 2018 By Philip Gefter -

Media Watch

Media WatchPage One

Winter 2001 By Véronique Vienne

Words

-

Words

WordsSpirituality Is Solidarity

Winter 2019 -

Essay

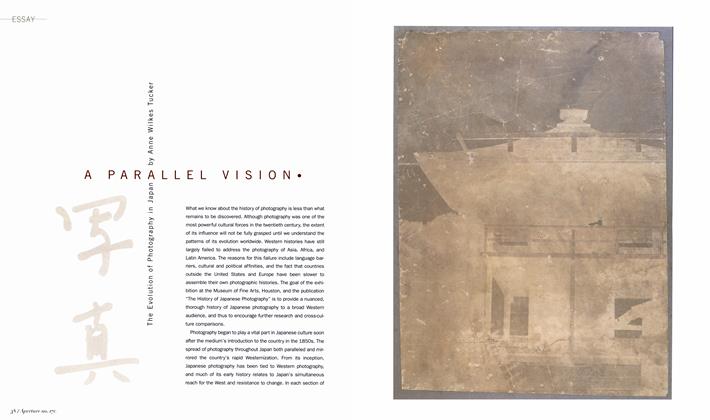

EssayA Parallel Vision: The Evolution Of Photography In Japan By Anne Wilkes Tucker

Spring 2003 By Anne Wilkes Tucker -

Words

WordsAddis Foto Fest

Summer 2017 By Brendan Wattenberg -

Words

WordsThe Black Photographers Annual

Summer 2016 By Carla Williams -

Words

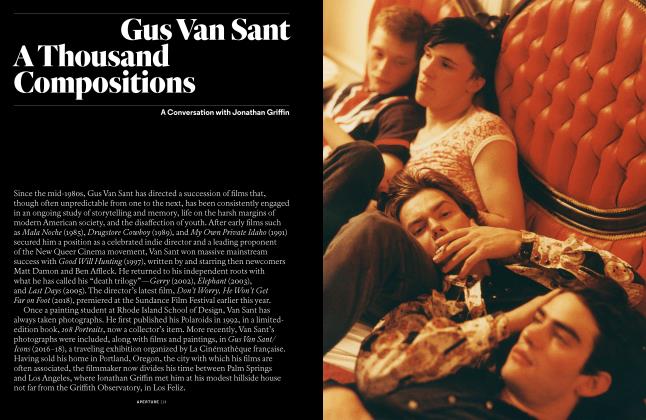

WordsGus Van Sant A Thousand Compositions

Summer 2018 By Jonathan Griffin