Words

Sovereignty: A Line In The Sand

Summer 1995 Jolene Rickard George Longfish, Zig Jackson, Pamela Shields Carroll, Ron Carraher, Hulleah TsinhnahjinnieOn November 4, 1924, a wiry man armed with an eagle feather and a string of wampum dared to challenge the most forceful countries in the world by defining terms for indigenous survival into the twentieth century. Cayuga Chief Deskaheh presented an official proclamation from the Iroquois Confederacy to the League of Nations in Geneva, documenting our independence and sovereignty as recognized in treaties with the Dutch, British, and American governments. Sixty-four years later Stephen Cornell, in The Return of the Native pointed out that as late as 1800, more than 80 percent of what are now the contiguous forty-eight states was still Indian land. By the end of the nineteenth century less than 5 percent was in indigenous hands. Positioning Deskaheh’s radical stance of declaring our independence and sovereignty after centuries of dispossession from our lands was like drawing a line in the sand at the ocean’s edge. What purpose this line?

Sovereignty is the border that shifts indigenous experience from a victimized stance to a strategic one. The recognition of this puts brains in our heads, and muscle on our bones. Vine Deloria, in We Talk, You Listen,2 placed sovereignty and power hand in hand, primarily with a view to perpetuating the existence of the group. Yet if I were to throw the term sovereignty out there at your basic Indian art opening, it would plummet to the floor, weighted down by ambiguity. One may wonder if the issue of sovereignty belongs in the cultural debate. I would strongly suggest that it does. David Novitz observes in Boundaries of Art,3 “The boundaries that distinguish high from popular art, good from bad, and art from life or reality do not exist independently of the social concerns, interests, aspirations, and values that form part of our everyday lives.” As part of an ongoing strategy for survival, the work of indigenous artists needs to be understood through the clarifying lens of sovereignty and self-determination, not just in terms of assimilation, colonization, and identity politics.

The call for sovereignty is part of my family’s work; you could say I cut my political teeth early. Deskaheh passed away at my grandfather Chief Clinton Rickard’s homestead soon after returning from that trip to the League of Nations. Inspired by Deskaheh’s work, my grandfather Rickard formed the Indian Defense League of America (IDLA) in 1926, dedicated to obtaining justice for Indian people. Growing up, I assumed that everybody knew that Native people used a number of strategies to survive, ranging from traditional governments to spiritual political movements to advocacy movements, such as the Society of American Indians and the IDLA in the early 1900s. Most of us are descendants of one strategy or another. And when we come across one another, our discussions are about how our people avoided extinction. It’s still how people talk in our communities, mostly playing down our resistance to the state. In this sense, the state is really the entire U.S. government and in my community the last battle was last week.

By the turn of the century, devastated by artillery and germ warfare, indigenous nations shifted shape by taking legal action, sparked by the Citizen Act of 1924, or what legal scholars R. L. Barsh and James Youngblood Henderson described in The Road4 as “a great experiment in coercive civilization. ” This act was viewed as the first step toward taxation and the loss of our political and territorial sovereignty. It was this final clip at the eagle’s wing that became the inspiration for sovereignty in the early twentieth century.

Today, sovereignty is taking shape in visual thought as indigenous artists negotiate cultural space. Unfortunately, the place where the Western-based art world permits indigenous visibility is in the narrow margin of identity politics. Or the official category of “the Other” in postmodern cultural criticism, which continues to reinforce all of the old stereotypes. The trouble with this construct is that the grooves in the collective brain are deeply scored with what Robert Berkhofer describes as “the white man’s Indian.” The challenge is to jump track and cut a new swath for indigenous expressions.5

It is not easy for America, or other nations whose identities are built on the bloody conquest of indigenous people, to rethink its internal relationships. For instance, Guntram F. A. Werther admits in Self-Determination in Western Democracies6 that “current political science theories about ethno-national movements in the First World cannot account for the success of aboriginal peoples, in part because political scientists have usually ignored aboriginal people’s [political] movements.” Restated, how is it that Indians slipped through the extermination net? Former president Ronald Reagan must have felt that way when, during an official visit to Moscow, he told university students “Maybe we made a mistake in trying to maintain Indian cultures. Maybe we should not have humored them in wanting to stay in that kind of primitive lifestyle.” The forced expropriation of Indian lands, confinement to reservations in the 1900s, the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) in the 1930s to the late ’40s, followed by the termination period from the 1940s to the ’60s —that’s what all this represents—humoring. Reagan’s perspective is just a continuation of policy established by the U.S. government in the 1800s. What can indigenous people expect when most nonNative people haven’t a clue about their own history, let alone ours?

The tendency to link identity construction to sovereignty is fair. What isn’t fair is the current dissection of indigenous identity issues without any historical context. Further, it’s a chilling irony that dialogue in the cultural apron has stagnated on identity construction. Projecting Indians either as a reflection of the natural “childlike” state of humankind, or as tax bandits hiding behind treaty loopholes, becomes just a new twist on misrepresentation. Gerald Vizenor’s claim in Manifest Manners7 that representations of Native Americans establish false notions of Indianness to serve as an idealized innocence for the West, elides and eliminates the realities of tribal cultures. It’s that invented simulation of Indianness that haunts photographic memories. Our artistic/cultural guideposts are lined up in galleries as continued reflections of the West. It is questionable whether non-Native people may fully understand photographs made by Indians, because it would require an ideological power shift.

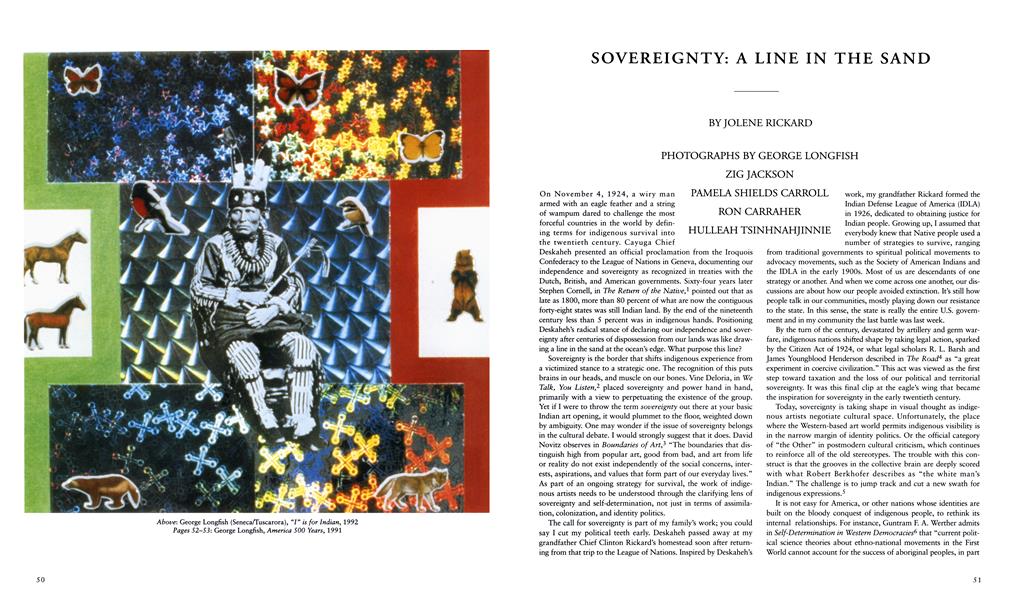

For instance, is Larry McNeil’s image of an eagle feather braced against the sky really Deskaheh pushing our ideas into the twenty-first century? Or is it just another easy-to-recognize Indian cultural symbol that is hip, but void of power? Same case with Zig Jackson’s recent “Indian Man in San Francisco” relocation parody. Is it Indian-out-of-hegemony-synch, insisting upon a feather fashion statement or is it about the lack of acceptance, or space, in this society for difference? Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie photochemically burned U.S.-issue identity numbers into her face, dulling full blood-brother’s and -sister’s radical edge, in the Nighthawk Series, making identity political. Do George Longfish’s iconographie Indians in America 500 represent the total embodiment of power—even suggesting some form of transformation—or subjugate soul-theft portraiture? Or, in the end, is all of this work about shifting states of reality?

Longfish’s silhouetted, photographically installed Indian is transformed by gradations of color. Fixed realities and unchanging worlds are no longer accepted by leading physicists like David Bohm and F. David Peat. In Lighting the Seventh Fire,8 Peat identifies Bohm’s hidden dimensions of the universe as “implicate,” or enfolded, order, in which the interconnections of the whole have nothing to do with locality in space and time, but exhibit an entirely different quality sometimes expressed as “unbroken wholeness.” To suggest that indigenous perceptions of the laws of nature are beginning to emerge in Western science is not to validate Longfish’s knowledge; it is to acknowledge it. For indigenous people, the political border of sovereignty has sheltered the primary paradigm of indigenous thought, and Longfish is documenting that space.

His work is parallel to another idea in physics, which acknowledges that the electron’s continuous exchange of energy with the universe means that it can never be isolated as an independent entity. Just as indigenous science teaches that all things connect and everything is relational, so it is with the electron’s relationship to the entire cosmos. The overlapping unity in Longfish’s work has a purpose, it is not simply a modernist aesthetic convention. Because duality and binaries have come to be expected from indigenous artists, Longfish’s work could be read as good versus bad, or reality versus imagined Indians. But I think he is setting up a more complex discussion about life, death, and rebirth.

Essentially, Peat and Bohm suggest that the true meaning of creativity depends on understanding the whole nature of order, going beyond the confines of physics—even science—to deal with the question of society and human consciousness. Longfish’s patterns viscerally map that understanding from the Western sphere to the indigenous, locating the journey to the center of the universe as being within the individual. The work of Longfish, Peat, and Bohm requires the mind to move into the middle ground between extremes. Like Longfish, the physicists recognize that creative intelligence may be regarded quite generally as the ability to perceive new categories and new orders between the older ones— in this case, disjointed extremes of the Western/non-Western dichotomy we are struggling to discard.

Photographs made by indigenous makers are the documentation of our sovereignty, both politically and spiritually. Some stick close to the spiritual centers while others break geographic and ideological rank and head West. But the images are all connected, circling in ever-sprawling spirals the terms of our experiences as human beings. The line drawn in the sand by people like Deskaheh was never simply a geographic or political mark. It has always been a taunt—an ancient lure hooking memories through time—shifting the way we see our lives. Photographs are just the latest lure.

1. Stephen Cornell, The Return of the Native: American Indian Political Resurgence (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 34.

2. Vine Deloria, Jr., We Talk, You Listen, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), p. 123.

3. David Novitz, The Boundaries of Art (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), p. 85.

4. Russell Lawrence Barsh and James Youngblood Henderson, The Road (Berkeley: University of California Press, California, 1980), p. 97.

5. Robert Berkhofer, Jr. The White Man's Indian; Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present (New York: First Vintage Books Edition, A Division of Random House, 1979).

6. Guntram F. A. Werther, Self-determination in Western Democracy: Aboriginal Politics in a Comparative Perspective (Westport, CT. and London: Greenwood Press, 1992), p. xv.

7. Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance (Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press, University Press of New England, 1994), back cover.

8. David F. Peat, Lighting the Seventh Fire: Spiritual Ways, Healing and Science of the Native American, (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1994), p. 284.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Creating A Visual History: A Question Of Ownership

Summer 1995 By Theresa Harlan -

Ghost In The Machine

Summer 1995 By Paul Chaat Smith -

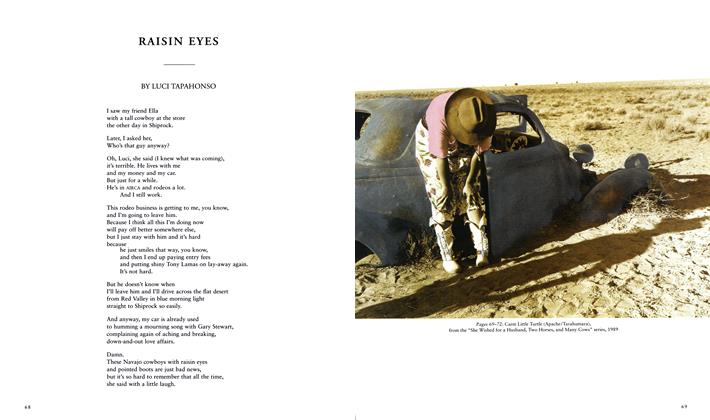

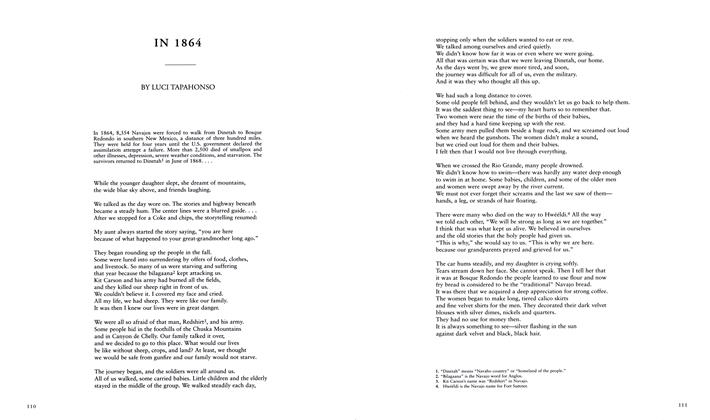

In 1864

Summer 1995 By Luci Tapahonso -

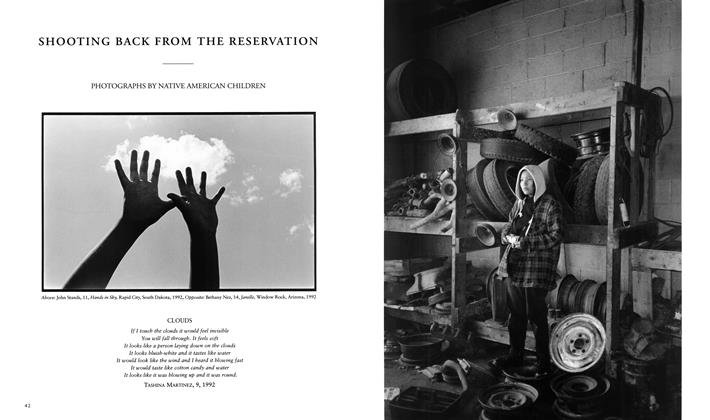

Shooting Back From The Reservation

Summer 1995 -

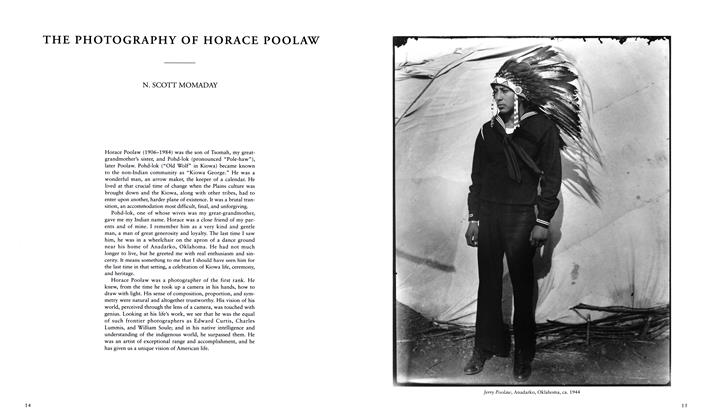

The Photography Of Horace Poolaw

Summer 1995 By N. Scott Momaday -

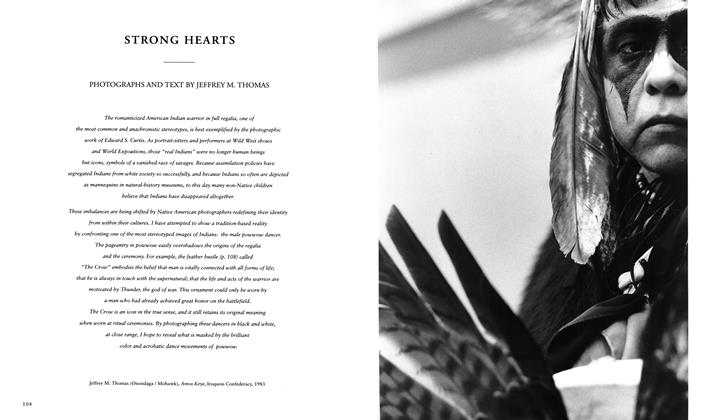

Strong Hearts

Summer 1995 By Jeffrey M. Thomas

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Words

-

Words

WordsAround The Kitchen Table

Summer 2016 -

Words

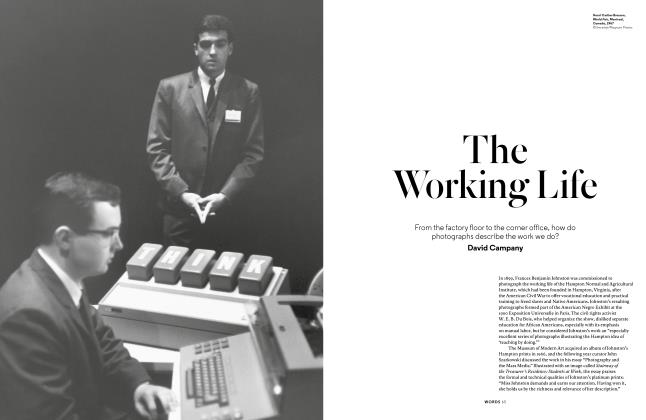

WordsThe Working Life

Spring 2017 By David Campany -

Words

WordsDecolonizing The Archive The View From West Africa

Spring 2013 By Jennifer Bajorek -

Words

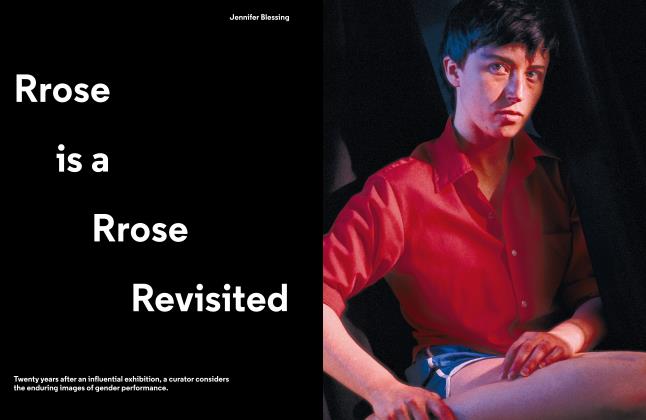

WordsRrose Is A Rrose Revisited

Winter 2017 By Jennifer Blessing -

Words

WordsThe Feminist Avant-Garde

Winter 2016 By Nancy Princenthal -

Words

WordsThe Lives Of Images

Summer 2013 By Trevor Paglen