ALONE WITH BASEBALL

ESSAY

Stephen Shore's Minor Leagues

Peter Schjeldahl

Baseball is beyond photogenic. It is pictorial. The quarter-circle defined by the foul lines is like a flat diagram of the eye's cone of vision. The game's action radiates out from and funnels into home plate, a sort of reversible vanishing point. No other sport is so ordered for comprehensive visibility, which can make a fan feel that the game is addressed to him or her alone. Irrational feelings of intimacy—in a spectacle that uses vast tracts of space and unmeasured stretches of time—are reinforced by the solitude of the players. Other team sports take place in rectangles, surge back and forth, and stir participatory, military emotions. Performing in focused view and mutual isolation, baseball players become figures of personal identification for the fan: hero, nemesis, brother, idiot brother. The theater of baseball frames images that are fraught with what Roger Angelí calls the fan’s “insatiable vicariousness.” Consult any sports page between April and October. Baseball photographers serve up a steady diet of variants on an archetypal bill of fare, flavored with the idiosyncrasies of particular players and the dramas of particular games.

Into the specular cult of baseball there came in 1978, on assignment for the New York Times to cover the Yankees in spring training, Stephen Shore. Shore was, as he remains, very much a fan, whose courting the previous year of Ginger Cramer, his wife ever since, had been conducted largely at Yankee Stadium, he tells me. “These people were my heroes,” he says of the Yankees he photographed then. But Shore was also, as he remains, an artist of steely originality, immune to conventional ways of looking at anything. He had proved his singularity in the early 1970s with some of the most compelling pictures ever taken of roadside and small-city America. Of all the “new topographical” photographers who fanned out across woebegone regions of the country in those days, Shore possessed both the most flexible style (no cookie-cutter minimalist compositions for him) and the most complex standards of what constituted an adequate picture. The shot had to be in color, for one thing, because the subjects were places where people lived, and color is life’s hormonal register. Black-and-white can show what something is. Color adds how it is, imbued with the temperatures and humidities of experience.

Shore’s Yankee suite—a reference necessary to an assessment of his recent work on minor-league ball, which is featured here—was both revelatory and, for a fan, eerily disturbing. It seemed to take no notice of the game of baseball as a structured contest, but only of its settings, equipment, and players as fragmentary objects of wonder. I think of a shot of the superb hitter Graig Nettles, poised to swing in an ugly batting-machine cage in desultory Florida surroundings. The beauty and intensity of his classic stance, in a pristine uniform, seem crazily autistic, under the circumstances. Shore’s photograph plunges the “insatiable vicariousness” of a fan—himself, digging Nettles—into indifferent, tacky reality like hot metal into ice water. The effect is cool, in a word. Shore is a definitively cool artist, not because he withholds his emotion but because he incorporates his emotion in his choice of subject and moment, then alienates it with frigid objectivity. Charles Baudelaire, who theorized the self-immolating aestheticism of the nineteenth-century dandy, would enjoy the Nettles picture, I’m very sure. Shore’s minor-league work is practically an essay on latter-day, vernacular dandyism: his own and that of baseball-mad young American guys.

Willie Mays, in retirement, was paid to spend a day coaching at a baseball clinic for children. Teaching a third baseman how to stand at the ready, Mays told him to bend his knees, keep his butt back, rest his glove on his thigh just so, and so on. With each instruction, the kid grew more miserably contorted. Finally Mays cried in exasperation, “Dammit, look like a ballplayer!” Instantly, the kid snapped into a posture that would have done Brooks Robinson proud. Mays had made the mistake of addressing the mind of a student and corrected it by appealing to a boy’s fantasy. I’m reminded of this story when I behold Shore’s photographs of Class A tyros: lads who were stars wherever they came from and now, in their first professional summers, on the lowest rung of the career ladder, begin to sense the odds against them. They are figures of dreaming incarnate. Whether they can hit serious breaking pitches or turn a double play with requisite crispness remains to be seen. Meanwhile, they will damn well look like major-leaguers. The catcher standing for the anthem—perhaps a scratchy recording on a tinny loudspeaker, in the little tank-town ballpark—might as well be Mike Piazza before the seventh game of a World Series. He’s perfect.

Shore’s would-be knights of the diamond are animate cousins of the streets and buildings which, as a roving New Yorker, he had discovered out in Nowhere-in-Particular, U.S.A. Those places are palpably as confident of their dignity and swagger as if they were Rockefeller Center. Such obstinate, touchy bravery is very American. We Americans are no good at giving a humble face to anything, however abject its identity or negligible its function. Putting up a good front is often our

recourse against fears of nullity. In a culture without secure social forms, image is everything. We talk the talk, walk the walk, and act as if. Who knows? With the right oomph, sincere sham may flip into actuality. Like other peculiarly American artists—Edward Hopper, Walker Evans, Andy Warhol—Shore has an instinct for truths that germinate between seeming and being. A sign of success, in this pursuit, is an aura of transfiguration that spreads like a purple stain, anointing things in a subject’s vicinity. Thus Shore’s lyrical shot of baseball gear strewn on green grass, a chance arrangement as delicate and satisfying, and as saturated with the spirit of a culture, as an echf-French still life by Chardin.

(continued on page 79)

(Stephen Shore continued from page 22)

My favorite picture in this series is the one of a player swinging at a pitch in a batting cage while, in the foreground, another player cocks his bat to take a practice swing at air. Their two bats happen to parallel each other. Mutually unconscious, the young men are at one in the sacred mystery of the swing. Their formal duplication suggests a world—a universe—of looping, baroque swipes, carving space everywhere with that soul-satisfying arc of elegant violence. For all we know, the two will be hard put to hit over .250 apiece for the season, and will spend the following summer back home in jobs at a drugstore and a gas station. But for the moment they are gods in Valhalla, wielding thunderbolts. It’s odd how we expend precious emotional energy on games that are played for vulgar fame and money by arrested adolescents. Shore’s subject is this oddity, which his photographs strip naked to our fascinated, perhaps slightly appalled gazes. Don’t we have anything better to do with our time? Speaking for myself: well, no. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

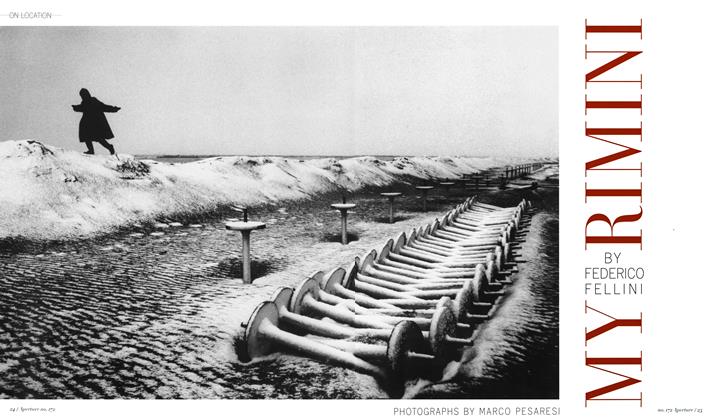

On Location

On LocationMy Rimini

Fall 2003 By Federico Fellini -

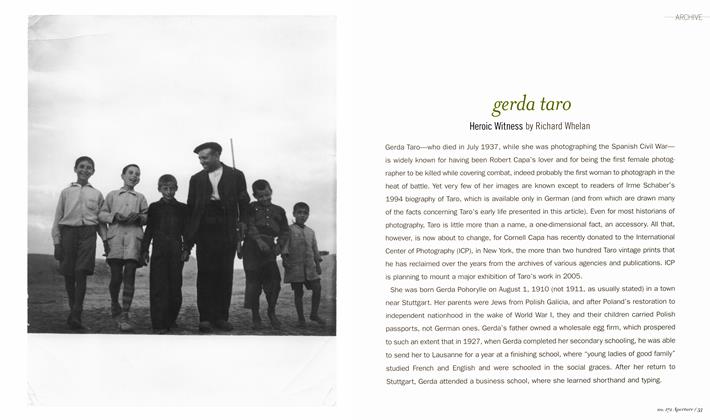

Archive

ArchiveGerda Taro

Fall 2003 By Richard Whelan -

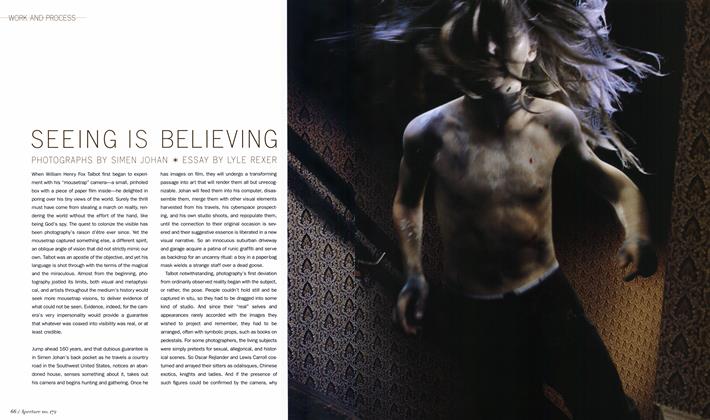

Work And Process

Work And ProcessSeeing Is Believing

Fall 2003 By Lyle Rexer -

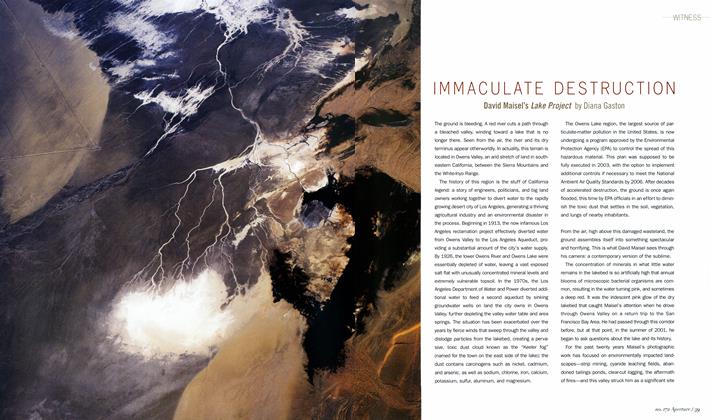

Witness

WitnessImmaculate Destruction

Fall 2003 By Diana Gaston -

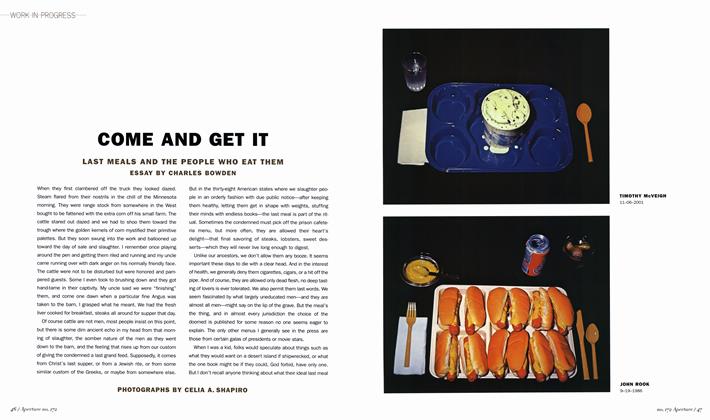

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressCome And Get It

Fall 2003 By Charles Bowden -

In Remembrance

In RemembranceCarole Kismaric, 1942-2002

Fall 2003 By R. H. Cravens

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Words

-

Words

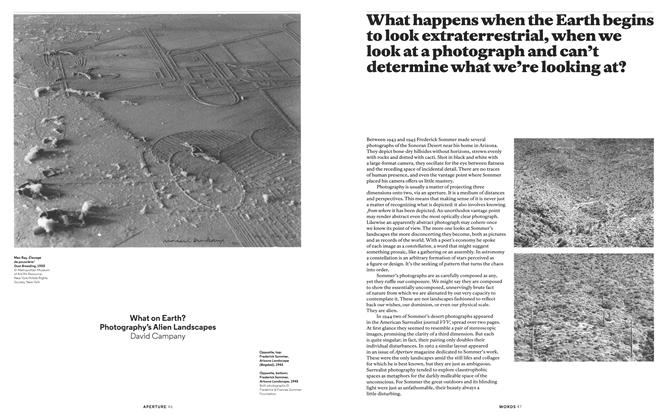

WordsWhat On Earth? Photography’s Alien Landscapes

Summer 2013 By David Campany -

Words

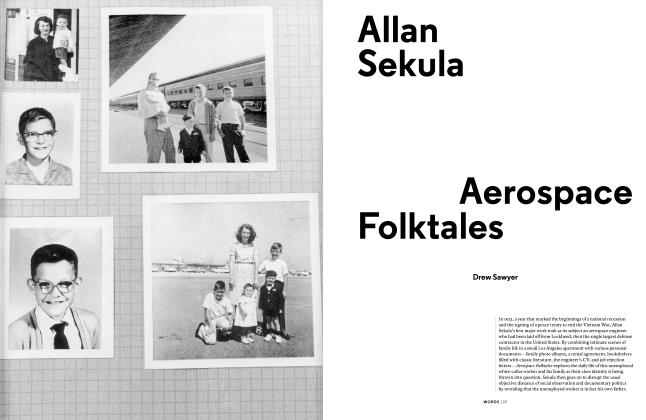

WordsAllan Sekula: Aerospace Folktales

Spring 2017 By Drew Sawyer -

Essay

EssayThe Forest For The Trees

Spring 2005 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Words

WordsPicturing Obama

Summer 2016 By Maurice Berger -

Words

WordsPrison Index

Spring 2018 By Pete Brook -

Words

WordsToward Poetic Vision

Fall 2018 By Rebecca Morse