Words

Diana Markosian Santa Barbara

A soap opera, a mail-order bride, and a Russian family's new life in California

Winter 2018 Rebecca BengalDIANA MARKOSIAN SANTA BARBARA

A soap opera, a mail-order bride, and a Russian family's new life in California

Rebecca Bengal

In October 1996, the Armenian American photographer Diana Markosian was seven years old, living with her family in Moscow, when her mother told her and her brother to pack their things; they were going on a trip. She didn’t say where. “We left immediately,” Markosian told me recently, “without even saying goodbye to our father.” They landed in a new world that felt completely foreign but eerily familiar too, almost as if it had been imprinted on her dreams.

“I remember the sunlight streaming through the windows,” Markosian said. “All the palm trees. We walked through the airport, and everyone was smiling and wearing Disney hats, and shorts and sneakers, and eating hamburgers. My mother wore a white eyelet dress, and she was holding a picture of this older man. I’d never seen her so anxious before.” A real-life version of the man in the picture approached, also smiling. Markosian, whose first name is pronounced Dee-ahn-ah, didn’t speak any English, but she understood that he seemed to know her mother and that he was offering the children orange juice to drink.

They had arrived in Santa Barbara, California, a place that, particularly for people living in post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s, symbolized a fairy tale. “Everyone knew Santa Barbara, no matter who you were,” Markosian told me of her early childhood, spent in between Yerevan, Armenia, and Moscow. The daytime series, named for the city where its three feuding fictional families lived, was the first American soap opera to be broadcast on Russian television. Santa Barbara's often outlandish and humorous touches didn’t always hold with American audiences, but in Russia, where it debuted in January 1992, its pop fantasy, dubbed in Russian, delivered a timely distraction from the recent collapse of the economy and the grim atmosphere that fell over the country.

Santa Barbara was a “national obsession of borderline-insane magnitude,” the Saint Petersburg-born novelist Mikhail Iossel wrote, in 2017, in Foreign Policy. According to Iossel, its title became shorthand for melodramatic behavior: “4Oh, I can’t stand those two, with their endless Santa Barbara!’” Russians hurried home for its broadcasts; they named their cats and dogs Mason, Eden, and Cruz after characters on the show. Graffiti appeared on buildings: “Santa Barbara Forevah!” The show was the total antithesis of Russia at the time—sunny, wealthy, vapid, glamorous, and, above all, free. Santa Barbara's run lasted about ten years in Russia, nearly paralleling Boris Yeltsin’s presidential term. Even today, the name is nostalgically embedded in the landscape— there is a Santa Barbara hotel in Crimea, for instance, with California-inspired architecture, and a Santa Barbara nightclub in Saint Petersburg, where, according to one travel site, clubgoers can find “the atmosphere of a permanent holiday.”

Markosian’s parents had studied economics and planned to become professors; in the Yeltsin years, they found themselves sewing and selling Barbie doll clothes to pay their bills. The children would leave the family’s studio apartment at five in the morning to collect recyclable bottles for money. “We were desperate,” Markosian said. At night, they watched television on whichever of their three temperamental sets happened to work. “Yeltsin came on nearly every evening, talking about the future of Russia, and everyone would tune in, because at any moment, Santa Barbara might come on,” Markosian said. “Santa Barbara was our window on what we believed American life to be.”

WORDS

As the project took shape, Santa Barbara the show emerged as a natural lens through which to view Svetlana's experience.

The man at the Santa Barbara airport, whose name was Eli, drove them down streets lined with palm trees to a house that Markosian perceived to have “endless rooms.” That first night, she woke to hear her mother crying in the bathroom. “She just kept saying, T can’t, I can’t,’” Markosian remembers. “Back home, she had been betrayed by the person who she had loved the most.” In Russia, after Markosian’s father had an affair and generally neglected the family, her mother, Svetlana, took out ads in newspaper classifieds sections for mail-order brides, exchanging letters with a few of the men who responded. That’s how they had come to America. “I’m not going back,” her brother, David, then eleven, told their mother that night. “There was the feeling that this was never in the cards for us, and yet we had made it,” Markosian told me. “That first year felt like magic.”

&

It’s a reimagining of that initial year in California that is the focus of Markosian’s mesmerizing and deeply layered project, also titled Santa Barbara (2018), which includes both photographs and a film made with a cast of actors and a production crew.

I spoke with Markosian in July, during a week when reports of Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids and the forced separation of immigrant families at the U.S.-Mexico border dominated the news. When she began envisioning the project, after the 2016 U.S. elections, she knew her mother would be the protagonist in the narrative. “This wasn’t my story,” Markosian said. “I didn’t make the decision. I was just a little girl, following her footsteps at the airport—and now trying to understand her and the sacrifice she made for us.”

As the project took shape, Santa Barbara the show emerged as a natural lens through which to view Svetlana’s experience.

In one of Markosian’s most trenchant pictures, a red carpet unfurls across the desert, and Svetlana, in her white eyelet dress, clutches the hands of her children, alone together on the cusp of an empty and desolate world. “After years of watching Santa Barbara, she couldn’t believe this was it,” Markosian said. “That there was not much culture beyond the beach. She had such hope, and found nothing for herself.”

Early on, Markosian drafted an episode-length screenplay.

“I knew that this wasn’t simply a project about photography, but was about storytelling,” she said. The photographer Doug DuBois, a mentor of Markosian’s, asked her, “Wait, you have a script, and you’re not going to film it?” “So I found myself auditioning actors for eight months,” Markosian recalled. She worked with Hollywood casting director Eyde Belasco, who had recently cast the 2018 film Sorry to Bother You. When finalizing her script, Markosian consulted Lynda Myles, one of Santa Barbara's longtime scriptwriters. “I didn’t want it to be a parody of the soap opera,” Markosian said, “but I wanted to convey the idea of the shared experience of a story.”

Photographs of the script, marked up with Myles’s notes, and a copy of a “show bible” for the writers are part of the project’s metafictional aspect, its conscious questioning of what it means to assemble and take possession of a story, whether the fictional universe of the show or the questioning and reimagining of a lived experience. Markosian’s Santa Barbara includes staged photographs, the film, and archival materials—classifieds like the ones Svetlana advertised in, promotions for the soap opera. Markosian added photographs and videos of casting calls for the eighty actors she auditioned for the role of Eli and the 263 who read for Svetlana, along with handwritten letters she asked the would-be Elis to write. The casting pictures are fascinating portrayals of human motivation—evident in the faces of the actors are variations on desire and longing, dreaming and survival. “I’d ask them, ‘Who is Svetlana?’ ‘She’s a mother first, looking for a better future.’ ‘Who is Eli?’ I’d say. ‘He’s a lonely man, looking for a fantasy.’”

Several months into the process, the original actress playing Svetlana quit. “It felt like my actual mother died,” said Markosian. Devastated, she posted ads in Russia, Georgia, and Armenia, eventually casting a thirty-year-old Georgian actress, Ana Imnadze. “I brought her here and watched her experience the United States for the first time.”

The staged photographs of Imnadze have a surreal and lucid quality of suspended belief, unshaken from the dream of the soap opera. In them, Diana and David and Svetlana are led by Eli into a sun-drenched and bewildering existence of Halloween and Disneyland, going to the beach and eating at restaurants, buying the Barbies and Legos they’d never owned before. “At first,” Markosian said, “Eli made my mother feel like a queen.”

Over the course of production and photography this spring, cast members began to explain Markosian’s own family back to her. “Ana’s face completely changes when she becomes my mother,” she said. In the photographs, the Santa Barbara light provides fleeting and sudden revelations, the conflicted range of expressions of a woman who has had to put herself in a frightening, demeaning situation in order to escape a similar one, a woman who has to pretend in order to survive and who, on some level, yearns to believe a version of the dream that convinced her to leave behind everything she’d known. “I’d ask Ana to pose a certain way and she’d say, ‘No, Diana, it’s not Svetlana,’” Markosian said. “The actor Gene Jones was at first reluctant to put on one of Eli’s costumes. ‘Jeans,’ he said, disgusted. ‘Really, Diana? You’d think he’d try harder.’”

Markosian added photographs and videos of casting calls for the eighty actors she auditioned for the role of Eli and the 263 who read for Svetlana.

Markosian’s suburban Santa Barbara scenes and domestic interiors inhabit a spiritual realm similar to that of Larry Sultan’s photographs of his Southern California parents in Pictures from Home (1982-91). Both series present keenly introspective approaches to depicting family. Eli reads the obituaries or watches Judge Judy\ Svetlana stares vacantly from the sofa or into the bathroom mirror at her new, hardly recognizable self. Absent from these photographs is the sense of love or a shared life that Sultan’s parents exhibited; the gulf between Eli and Svetlana is palpable in the pictures. “It adds a sense of melancholy,” Erin O’Toole, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s associate curator of photography, who is curating the institution’s 2020 exhibition of Santa Barbara, told me. “Both Larry and Diana are looking at their family from the perspective of their parents, embodying them.” Jim Goldberg, for whom Sultan was a mentor, and who explores his own personal history in his 2016 photobook, The Last Son, had recommended Markosian’s project to the department. “There’s this idea in both Sultan’s and Markosian’s work about how much the Hollywood or television ideal imprinted on people and affected what they thought they wanted out of their lives,” O’Toole said.

In Dad on Bed (1984), from Pictures from Home, Irving Sultan sits on the edge of his bed, an expression of ennui crossing his face. “I look like a full-on lost soul and I look at the picture and I say ‘That’s not me!’” Sultan chastised his son. “‘In fact you went even further,” Larry corrected him. “You said, ‘That’s not me sitting on the bed, that’s you sitting on the bed. That’s a selfportrait.’ And I thought that was right.”

At twenty-nine, Markosian is not much younger than Svetlana was—thirty-five—when they came to America. A graduate of the Columbia University School of Journalism and a Magnum Photos nominee, Markosian has lived mostly out of a suitcase for years, traveling on magazine assignments around the world. When we first spoke, she was in Amsterdam, preparing for a trip to Cuba early the next morning; it was evident how similarly driven she and Svetlana are. “She’s not very casual with her life,” Markosian said of her mother, who, with her brother’s help in those early years, applied for a visa, learned to drive, got a job selling men’s ties at a department store, went to night school, and earned a second PhD. “Mail-order bride” is a bit of a misnomer—Svetlana was not obliged to marry Eli, but in order for them to remain in America, she did. Within a year of moving to America, she married him in a Las Vegas wedding.

“I had called him ‘Father,’” said Markosian of Eli, as she had had no contact with her own. “But my mother had outgrown him, and I think he knew it. I realized it when we were going to move. We were sitting in the front seat of a U-Haul at a gas station, waiting on my mother, and I remember Eli looking out the window and saying, ‘I’m so tired of this.’ I said, ‘Of what?’

And he goes, ‘Of everything.’And right then my mother bounded over, smiling and shouting, ‘Let’s go!’ She was so full of life.

It struck me suddenly: she was at the beginning of hers, and he was nearing the end of his.”

They’d planned to stay at a hotel and move to San Francisco together, but Eli abruptly filed for divorce. “The man who had saved us when we were desperate had abandoned us,” Markosian said. Her brother was already in college, but for a year, she and her mother lived in a women’s shelter to save money.

Markosian hasn’t seen Eli since she was fifteen. She remains extremely close with her mother and brother, who have been involved with the project since its inception. Her mother now lives in Portland, Oregon, and runs her own accounting firm. When Markosian visits, she sometimes finds Svetlana doing Pilates, accompanied by reruns of Santa Barbara. “At times,

I’ve been so angry at my mother,” Markosian said. “But she understood that I needed to understand her. Still I’d yell, ‘I just don’t get you!’And she’d tell me, ‘You don’t have to get me, Diana, just love me.’”

Several years ago, Markosian reconnected with her biological father and made two series of photographs, Mornings (2016) and Inventing My Father (2013-14). He was living in the family’s mostly unchanged apartment in Yerevan. “He had kept essentially a time capsule of our possessions from when we had gone missing,” she recalled. “There was a photo-album, a clock we’d had on the wall. To me, these things felt like treasures.”

For Santa Barbara, she had wallpaper made according to an old family photograph.

When Markosian returns to Russia and Armenia this year, she plans to photograph flashbacks for the film as still images.

“I am trying to re-create the light I remember as a kid,” she said. “In Russia, it was always suffused with this feeling that it’s not enough. Santa Barbara gave us hope for something more. When we got there, it was a brightness I had never seen, almost impossible to believe.”

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

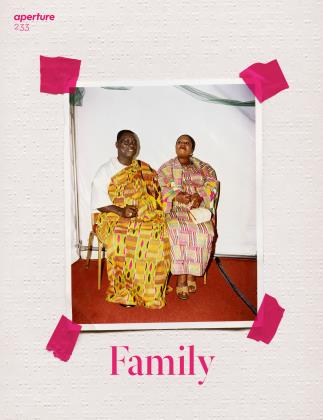

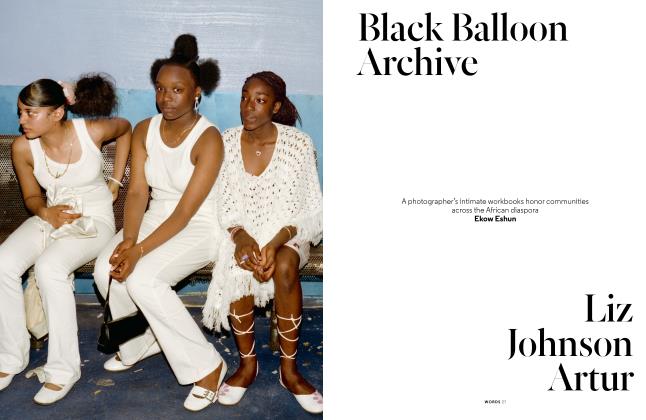

WordsBlack Balloon Archive Liz Johnson Artur

Winter 2018 By Ekow Eshun -

Pictures

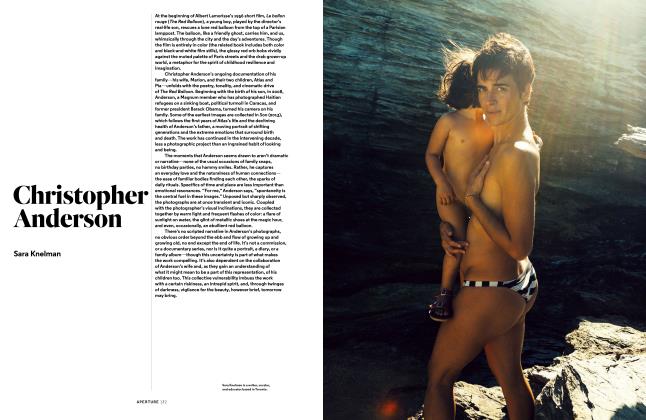

PicturesChristopher Anderson

Winter 2018 By Sara Knelman -

Words

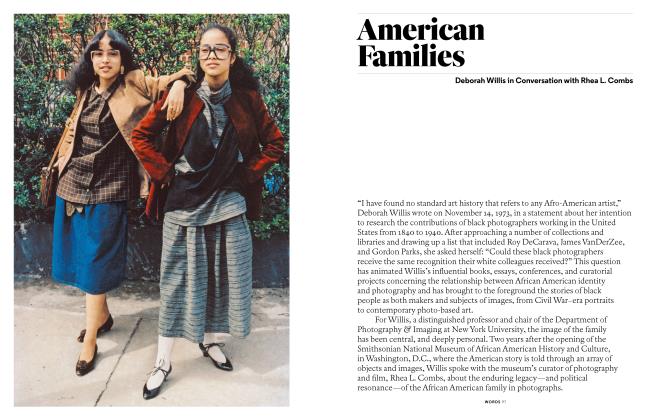

WordsAmerican Families

Winter 2018 -

Words

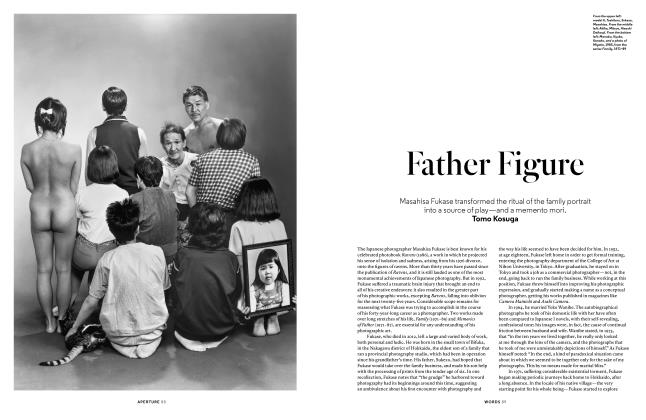

WordsFather Figure

Winter 2018 By Tomo Kosuga -

Pictures

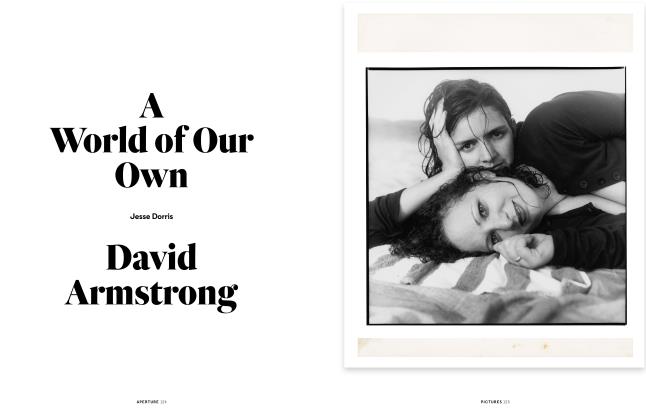

PicturesA World Of Our Own David Armstrong

Winter 2018 By Jesse Dorris -

Feature

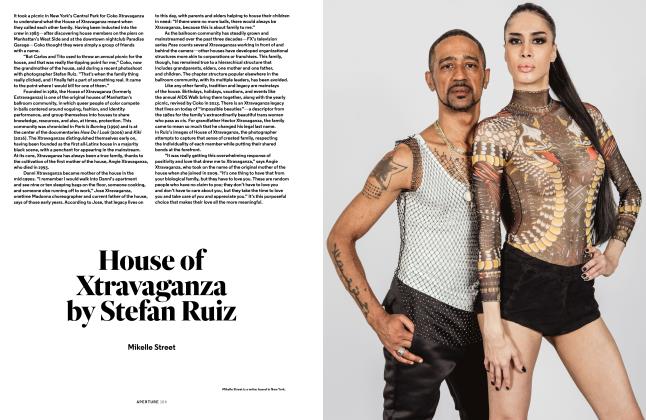

FeatureHouse Of Xtravaganza By Stefan Ruiz

Winter 2018 By Mikelle Street

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Rebecca Bengal

-

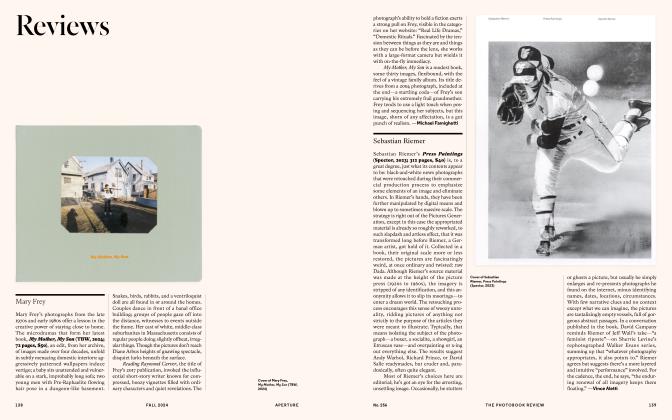

Reviews

FALL 2024 By Michael Famighetti, Vince Aletti, Rebecca Bengal, 3 more ... -

Words

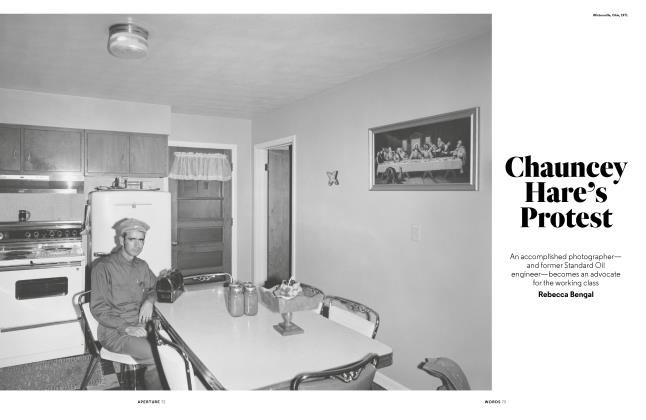

WordsChauncey Hare’s Protest

Spring 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Spotlight

SpotlightNatalie Krick

Winter 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesAlex Prager

Summer 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

WordsFilm Studies

Summer 2020 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

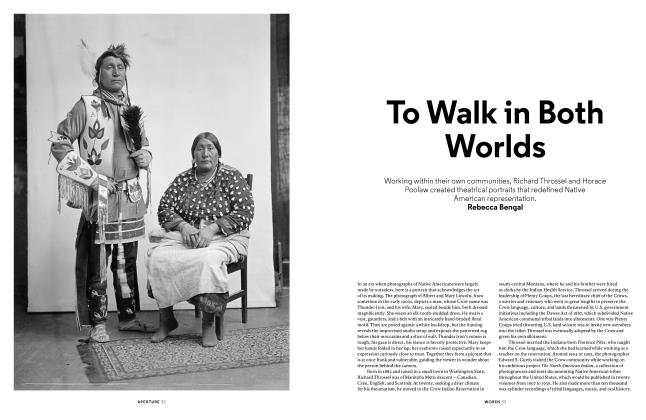

WordsTo Walk In Both Worlds

Fall 2020 By Rebecca Bengal

Words

-

Words

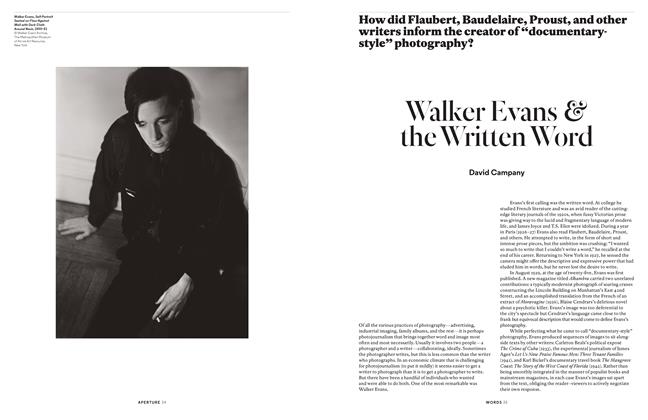

WordsWalker Evans & The Written Word

Winter 2014 By David Campany -

Words

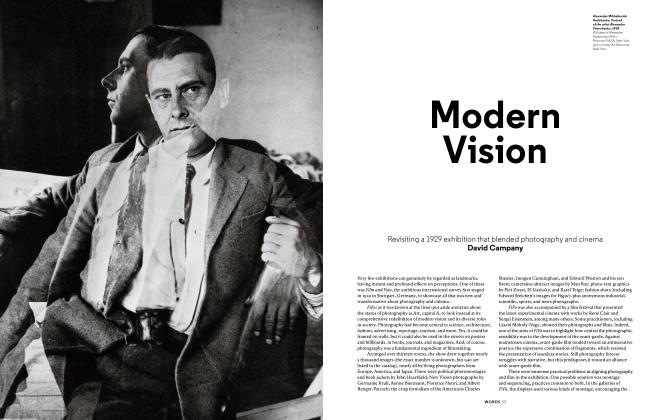

WordsModern Vision

Summer 2018 By David Campany -

Words

WordsRaw Land

Summer 2017 By Morad Montazami -

Words

WordsSchool Days

Summer 2017 By Sean O’Toole -

Words

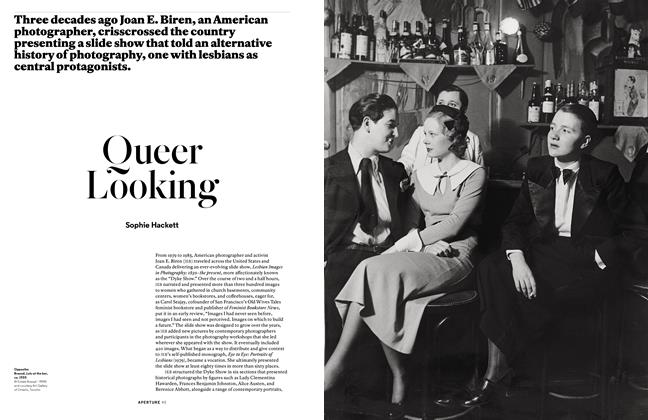

WordsQueer Looking

Spring 2015 By Sophie Hackett -

Essay

EssayThe Less-Settled Space Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, And Garry Winogrand

Spring 2011 By Ulrich Baer