Rediscovered Books and Writings

Redux

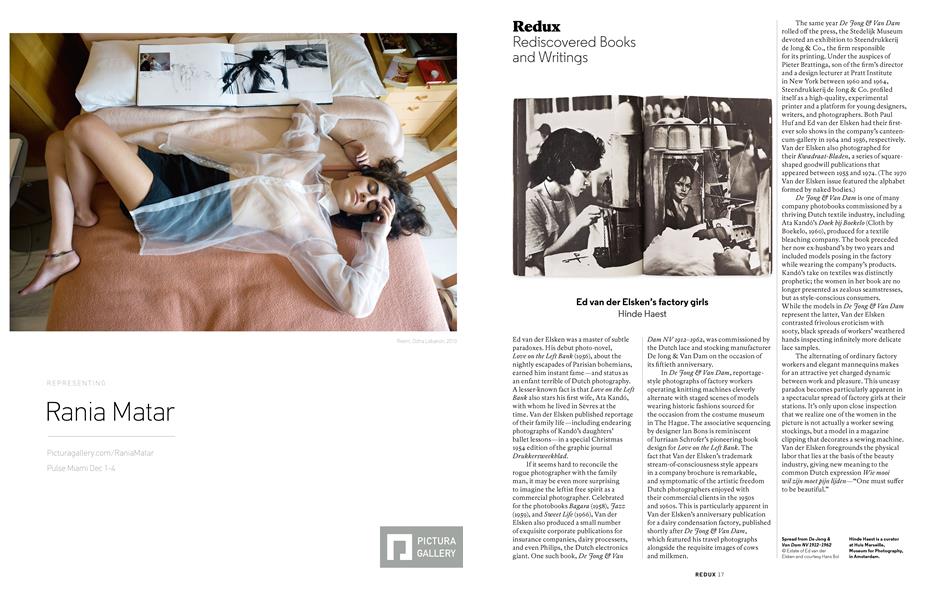

Ed van der Elsken’s factory girls

Hinde Haest

Ed van der Elsken was a master of subtle paradoxes. His debut photo-novel, Love on the Left Bank (1956), about the nightly escapades of Parisian bohemians, earned him instant fame—and status as an enfant terrible of Dutch photography. A lesser-known fact is that Love on the Left Bank also stars his first wife, Ata Kandó, with whom he lived in Sèvres at the time. Van der Elsken published reportage of their family life—including endearing photographs of Kandó’s daughters’ ballet lessons—in a special Christmas 1954 edition of the graphic journal Drukkersweekblad.

If it seems hard to reconcile the rogue photographer with the family man, it maybe even more surprising to imagine the leftist free spirit as a commercial photographer. Celebrated for the photobooks Bagara (1958), Jazz (1959), and Sweet Life (1966), Van der Elsken also produced a small number of exquisite corporate publications for insurance companies, dairy processers, and even Philips, the Dutch electronics giant. One such book, De Jong & Van

Dam NV 1912-1962, was commissioned by the Dutch lace and stocking manufacturer De long & Van Dam on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary.

In De Jong & Van Dam, reportagestyle photographs of factory workers operating knitting machines cleverly alternate with staged scenes of models wearing historic fashions sourced for the occasion from the costume museum in The Hague. The associative sequencing by designer Ian Bons is reminiscent of lurriaan Schrofer’s pioneering book design for Love on the Left Bank. The fact that Van der Elsken’s trademark stream-of-consciousness style appears in a company brochure is remarkable, and symptomatic of the artistic freedom Dutch photographers enjoyed with their commercial clients in the 1950s and 1960s. This is particularly apparent in Van der Elsken’s anniversary publication for a dairy condensation factory, published shortly after De Jong & Van Dam, which featured his travel photographs alongside the requisite images of cows and milkmen.

The same year De Jong & Van Dam rolled off the press, the Stedelijk Museum devoted an exhibition to Steendrukkerij de long & Co., the firm responsible for its printing. Under the auspices of Pieter Brattinga, son of the firm’s director and a design lecturer at Pratt Institute in New York between i960 and 1964, Steendrukkerij de long & Co. profiled itself as a high-quality, experimental printer and a platform for young designers, writers, and photographers. Both Paul Huf and Ed van der Elsken had their firstever solo shows in the company’s canteencum-gallery in 1964 and 1956, respectively. Van der Elsken also photographed for their Kwadraat-Bladen, a series of squareshaped goodwill publications that appeared between 1955 and 1974. (The 1970 Van der Elsken issue featured the alphabet formed by naked bodies.)

De Jong & Van Dam is one of many company photobooks commissioned by a thriving Dutch textile industry, including Ata Kandó’s Doek bij Boekelo (Cloth by Boekelo, i960), produced for a textile bleaching company. The book preceded her now ex-husband’s by two years and included models posing in the factory while wearing the company’s products. Kandó’s take on textiles was distinctly prophetic; the women in her book are no longer presented as zealous seamstresses, but as style-conscious consumers.

While the models in De Jong & Van Dam represent the latter, Van der Elsken contrasted frivolous eroticism with sooty, black spreads of workers’ weathered hands inspecting infinitely more delicate lace samples.

The alternating of ordinary factory workers and elegant mannequins makes for an attractive yet charged dynamic between work and pleasure. This uneasy paradox becomes particularly apparent in a spectacular spread of factory girls at their stations. It’s only upon close inspection that we realize one of the women in the picture is not actually a worker sewing stockings, but a model in a magazine clipping that decorates a sewing machine. Van der Elsken foregrounds the physical labor that lies at the basis of the beauty industry, giving new meaning to the common Dutch expression Wie mooi wil zijn moet pijn lijden—“One must suffer to be beautiful.”

Hinde Haest is a curator at Huis Marseille, Museum for Photography, in Amsterdam.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsListening For Eggleston

Fall 2016 By John Jeremiah Sullivan -

Pictures

PicturesMichael Schmelling Your Blues

Fall 2016 By Kelefa Sanneh -

Words

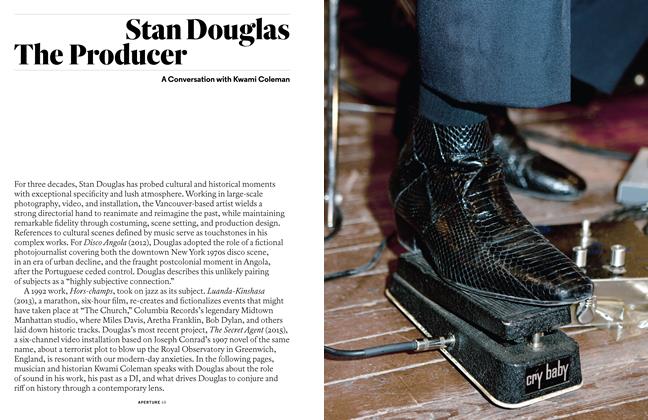

WordsStan Douglas The Producer

Fall 2016 By Kwami Coleman -

Words

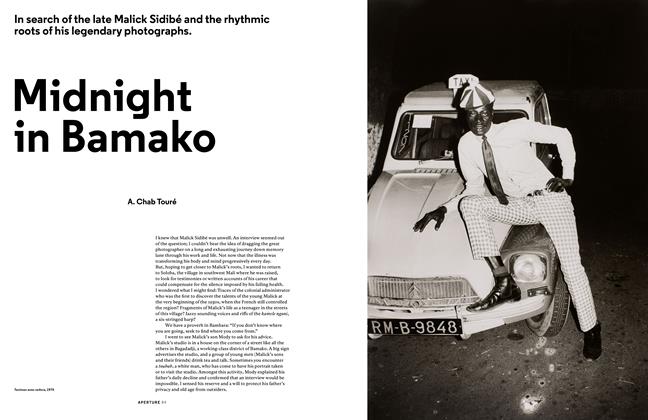

WordsMidnight In Bamako

Fall 2016 By A. Chab Touré -

Pictures

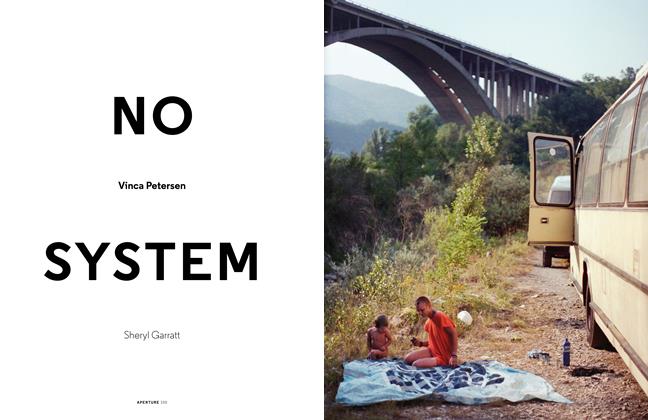

PicturesNo System Vinca Petersen

Fall 2016 By Sheryl Garratt -

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Redux

-

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2018 By Alistair O’Neill -

Redux

ReduxBern Porter's Dieresis

Summer 2015 By David Campany -

Redux

ReduxThe Critical Writings Of Sadakichi Hartmann

Spring 2014 By Diana C. Stoll -

Redux

ReduxLew Thomas's Structural(ism) And Photography

Winter 2014 By Erin O’Toole -

Redux

ReduxD.H. Lawrence's "Art And Morality"

Summer 2014 By Geoff Dyer -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Winter 2017 By Maika Pollack