Stan Douglas The Producer

Kwami Coleman

For three decades, Stan Douglas has probed cultural and historical moments with exceptional specificity and lush atmosphere. Working in large-scale photography, video, and installation, the Vancouver-based artist wields a strong directorial hand to reanimate and reimagine the past, while maintaining remarkable fidelity through costuming, scene setting, and production design. References to cultural scenes defined by music serve as touchstones in his complex works. For Disco Angola (2012), Douglas adopted the role of a fictional photojournalist covering both the downtown New York 1970s disco scene, in an era of urban decline, and the fraught postcolonial moment in Angola, after the Portuguese ceded control. Douglas describes this unlikely pairing of subjects as a “highly subjective connection.”

A1992 work, Hors-champs, took on jazz as its subject. Luanda-Kinshasa (2013), a marathon, six-hour film, re-creates and fictionalizes events that might have taken place at “The Church,” Columbia Records’s legendary Midtown Manhattan studio, where Miles Davis, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, and others laid down historic tracks. Douglas’s most recent project, The Secret Agent (2015), a six-channel video installation based on Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel of the same name, about a terrorist plot to blow up the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, is resonant with our modern-day anxieties. In the following pages, musician and historian Kwami Coleman speaks with Douglas about the role of sound in his work, his past as a DJ, and what drives Douglas to conjure and riff on history through a contemporary lens.

WORDS

Kwami Coleman: I look at the photographs from your series Disco Angola (2012) and the stills from your film Luanda-Kinshasa (2013) for the same reason that I enjoy recordings. They provide me with an insight into the past. Anyone dealing with a medium that freezes a moment, an ideology, a Zeitgeist, becomes obsessed with the past. In your work, there’s a notion of going back to some kind of ideal world—a time before colonial interaction and disturbance. How are you careful about not romanticizing the past?

Stan Douglas: The past moments that I choose to depict are usually pretty nasty. The only idealized instance would be that of Luanda-Kinshasa, which is almost like speculative fiction. I’m not depicting anything that really happened, but rather something that might have happened. It could have been that Miles Davis decided to pick up on Afrobeat and incorporate that into what he was doing, his pancultural synthesis. But the idea of all these cultures coming together and making something new out of their differences is what I find quite appealing. We’re always being asked to be our own individual tribe, but not to think about the universal. I’m reading somebody like Miles in that moment as trying to think about how he can, in symbolic form, play out the possibilities of humans being together in this way. That’s one of the best things music can do. It can provide a model of how people can endure time together.

KC: In Luanda-Kinshasa, we have living jazz musicians representing fictional jazz musicians from the 1970s. So you’re using present musicians to evoke but also inscribe, both aurally and in a visual way, past works of Miles Davis’s and Joe Henderson’s. What does jazz mean to you and your work?

SD: Well, I love the music but I can’t play it. I wasn’t there when Davis’s On the Corner (1972) was recorded, and I want to find a way of experiencing it. The main reason that an artist makes art is so they can see it. And I presume that a musician wants to make music in order to hear it, or to be in it. That’s why I do it. For example, I can’t play any of the instruments you hear in Luanda-Kinshasa (although I played drums when I was in high school), but I was able, through the process of editing, to arrange that music, to be involved in musical creation.

KC: So you become kind of like Miles Davis and Columbia Records producer Teo Macero in the control booth.

SD: That was the idea, exactly. This is the way they were making that music in this period, by editing improvised takes. I thought I could do that with the whole enchilada, with both picture and sound. It was a bit of a puzzle to work out, but it was actually really enjoyable to do because the music was so good.

Whenever you see music in an art gallery, it’s either classical music or rock music. I wanted to hear something else. That was my secret motivation for the piece. But sometimes it backfires on you. There was an article in a magazine that called the work “an epic love letter to 1970s rock ’n’ roll.” And I was like, What?

KC: You know a lot about jazz. As a musician myself, it’s wonderful when people take the craft that you’ve devoted your life to very seriously. And you take it seriously in multiple iterations, like disco or electro, Afrobeat, Angolan jazz. So what does jazz mean to you?

SD: All kinds of things. One key idea for me is the endlessness of the music. That the songs aren’t just songs on paper. They’re living things, which then get reinterpreted by people and generations over time. The transformation of the jazz standard by a bebop musician is wonderful. With the idea of variation, you know what a piece is, but then, with that as a guide, you realize how far it’s diverged from that original source. That gesture is something I’ve used throughout my career, inspired by the example of jazz music. Luanda-Kinshasa raises past motifs in new contexts. We hear what we thought we knew in a new way.

KC: The performance captured on some kind of medium, like a record, is not the final say. So rather than just look at the score and see the score as this sort of self-enclosed work, now we’re dealing with a multiplicity of meaning by virtue of something being recorded. Then, in the jazz tradition, knowing that just because Miles plays Milestones this way in April of 1958 does not mean he plays it the same way in May of 1958, and so on.

SD: Or when he recorded something from Bitches Brew (1970), and then took it to the studio and made his final edit of it, he finished composing it. At that point, the template, the song, was written. He finished writing it. Then he could elaborate on it later. It’s just a different idea about how you form that music, how you formulate that utterance. Is it through conversation? Is it through text? Or is it through the ideas you can get from hearing something that’s in a way random?

The recording mechanism, just like a photograph, captures what we don’t intend. We hear sounds we didn’t realize were there.

KC: Do you see any part of your process as being improvisational?

SD: That is definitely part of the process. Not entirely knowing what’s going to happen, and then setting things in motion, and then deciding when to stop, when it’s done, when we get to the place we need to be. Eventually, that becomes solidified as a picture, I suppose.

KC: One of the distinctive qualities of improvisation (and any musician would say this) is that unless you’re doing a solo show, it doesn’t happen alone. It’s always done in conversation, in dialogue with the other musicians you’re working with, and with the audience. To what degree do you see yourself as being one of the musicians?

SD: On Luanda-Kinshasa I talked to Jason Moran extensively.

The musicians had an idea of what I was looking for, what records I was interested in.

KC: Which?

SD: On the Corner and Manu Dibango’s “Soul Makossa” (1972).

KC: When did you discover jazz, if it was a discovery? Or was it part of your family upbringing?

SD: I’m named after Stan Kenton, but I don’t like Stan Kenton. I was kind of unaware of jazz. My parents divorced when I was quite young, but there was a John Coltrane record, Impressions—

KC: Early 1961.

The recording mechanism, just like a photograph, captures what we don’t intend. We hear sounds we didn’t realize were there.

SD: Yes, Impressions and [whistles opening motif of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme (1965)].

KC : A Love Supreme?

SD: Exactly. My father left those behind, and “Soul Makossa,” and other things, too. Those were the ones I took with me when I left home. The Coltrane I especially fell in love with. The song ‘India” is one of the few songs that can make me cry.

KC : It’s a beautiful tune. It’s interesting to me that your ear goes to that moment, too, because that was exactly the moment in which you had African American musicians reestablishing ties to the African continent, to South Asia, to these parts of the world that have basically been erased by the West. As you were listening to this music in Canada, were you forming your own connections to a much broader world?

SD: I tried to pay attention to them. I had a fascination with Brazil as well, just for being the New World but not like the one in the north—it had a different permutation of Africans and Europeans and Indians in that situation. But I could never quite identify with what was happening in the States, or identify with Africa, without having been to Africa. Because Africans had their own thing going on, which was very different. As a Canadian kid, I was always being asked to represent the Afro-American experience, but I had no idea what that was because I didn’t live here in the U.S., so it was always this odd condition of alienation.

KC: It’s a type of alienation that occurred in this country, too, where African Americans sometimes feel like they have to acquiesce to this overarching notion of African American-ness, when really, cultures can be so localized, so specific. I know this because my father was one of these people in the 1960s who had a deep interest in Africa, wanting away of reclaiming it because that history, that connection to the continent, was violently severed through slavery. That generation in particular—

John Coltrane and other musicians around that time— was invested in finding those cultures, and also the beauty of those cultures.

I found a review in Artforum of Disco Angola from 2012. There was a little phrase in there that caught my eye, speaking about what kind of music was being played in these pictures: “The barely plausible connections to American disco.” This idea that somehow American disco probably was not happening in a place like Angola—I don’t think that’s the case at all.

SD: I thought of them as very separate. It was a highly subjective connection I was making. It’s not that you had American disco in Angola or Angolans in disco. It’s just that these two things are happening simultaneously, and in two very different ways a space of autonomy was carved out by people for themselves that was interfered with by exterior forces, inasmuch as the U.S. and the USSR turned what was local in Angola at that time into a proxy Cold War conflict that would become a civil war lasting for eighteen years. Thousands of people died. Disco was a utopian space carved out by a counterculture in the ruins of New York City that was then sanitized and commercialized.

KC: Don’t you find that even disco is something of a misnomer? Because what we’re really talking about is dance music that was played from records. We’re talking about DJ culture, discotheques. Of course, all across the African continent there were discotheques; you’d find musicians who had an ear to what was happening in the States, maybe an ear to what’s happening in Europe, but also to what was happening around the continent. A figure like Felá Kuti, for instance, was listening to Ghanaian music such as highlife, and also listening to James Brown.

SD: It’s not that it’s being brought to Angola or it’s a separate thing. The Angolan metaphor has got nothing to do with the musical condition. It’s just got to do with political conditions. Whatever it was that Angola could have been was disrupted by exterior forces, just like whatever disco could have been was disrupted by commercial forces. It’s a very weird, highly subjective aesthetic identification between them that I’m making in the photographs—they both feel to me like their potential for autonomy was ruined by external forces. That’s all I’m getting at.

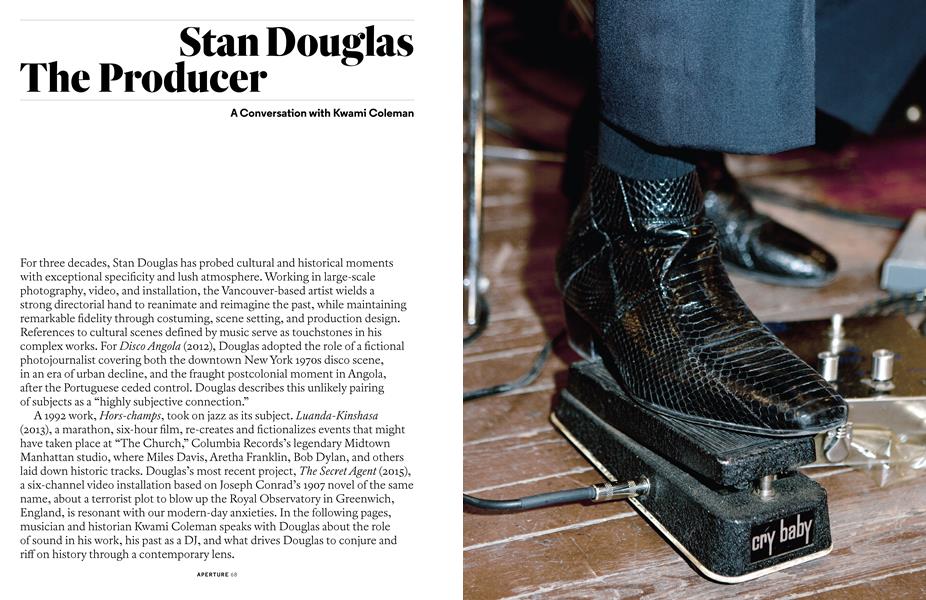

But, the DJ culture is something that’s very close to my heart, because my second job was as a DJ. My first job after high school in Vancouver was at a coffee bar. Next door there was a gay club that was not doing so well on Fridays, and I convinced them if I played records my friends would come, and actually for a couple of years I had a regular Friday night gig. I used to make pause-button edits with my cassette deck, and when I came back from a trip to New York, where I had seen Herbie Hancock play with Grand Mixer D.ST at the Roxy, I learned how to play D.ST’s mix of Hancock’s “Rockit” with Time Zone’s “The Wildstyle.” The problem was that no one in Vancouver recognized that I was

Every historical fiction, like every science fiction, is usually an allegory of the present.

manipulating this music, because they didn’t recognize the music I was playing in the first place.

KC: That adds so much context to your work. Because essentially you’re doing that, too, in the live performances filmed for Luanda-Kinshasa.

SD: Yes, and I had very concrete experience, being a DJ, of how that works and how you can build a situation. I felt I was building a space when I was doing a set. A space created over time: different kinds of spaces by manipulating existing cultural artifacts. That experience definitely informs all of my work.

KC: You mentioned Herbie Hancock, who is obsessed with technology, and Grand Mixer D.ST, who is known for his use of technology. And everything about your biography seems to do with technology.

SD: Well, there are all these tools—tools to a new end. Some technologies maybe have a patina of age, a certain timbre. For Luanda-Kinshasa we found the guy who made the Mu-Tron III, an effects pedal. Everything’s got a Mu-Tron on it. The bass has got a Mu-Tron, the Rhodes has a Mu-Tron, the Wurlitzer, the rhythm guitar.

KC: Sometimes it’s hard for us to really hear how the music sounded then, because the technology didn’t allow for the best kind of fidelity, whereas now we live in a world with digital everything; fidelity is arguably at a higher point than it’s ever been. I wish some of the old footage of people like Miles Davis, or even Sun Ra, would have all the fidelity and crispness that everything has today. When I saw LuandaKinshasa, I thought, Ah, there it is. Except it’s not necessarily Miles or any of the musicians we’ve been talking about.

These are new musicians who have been transported back in time.

SD: People sometimes ask me, “Why doesn’t it look like the past exactly?” I say, “Well, I’m not interested so much in using older technology to represent these things, like having grainy black-and-white film. I want to sort of time travel and see the past in the best resolution possible, and that’s why it looks the way it does.”

KC: Why, though? What does it do for you?

SD: To experience something I didn’t experience, and something that I may experience in fragments, and put those together just to try to get the whole gestalt, to know what it feels like to be there—to not forget what that experience could have been, and what a contemporary version of that experience might be.

KC: You have a clear interest in revolutionary moments, with your film The Secret Agent (2015) being perhaps the most explicit. Can you speak about revolutions, maybe your interest in historical revolutions, or inciting your own revolution, if you like?

SD: I’ve always been interested in liminal moments, and there are few things more liminal than a revolution. They are reminders that the way we live today is not the only way possible and that present conditions grew out of something else. The Secret Agent is a six-channel video with eight channels of audio, so the

story surrounds you, sometimes overwhelmingly. It is set in the aftermath of the Portuguese Carnation Revolution, but it is really a meditation on terrorism: in the late nineteenth century, the setting of the eponymous Joseph Conrad novel upon which the work is based; in the mid-1970s, during the “Hot Summer of’75,” when there were bombings and other terrorist acts throughout Portugal; and, of course, today. Every historical fiction, like every science fiction, is usually an allegory of the present. During the “Hot Summer” there were extreme rightand left-wing groups that used exactly the same means to try to achieve completely different ends. The weirdness about terrorism is that it is an emphatic gesture that is utterly ambiguous at the same time.

One of many things I’m researching right now is 2011, and particularly the riots in London after the Mark Duggan killing.

I feel it was a revolutionary expression that had no form and no way of representing itself properly. In a sad way it will probably be remembered as our 1848.

Kwami Coleman is a pianist, composer, and musicologist specializing in improvised music. He is Assistant Professor and Faculty Fellow at the Gallatin School of Individualized Study, New York University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsListening For Eggleston

Fall 2016 By John Jeremiah Sullivan -

Pictures

PicturesMichael Schmelling Your Blues

Fall 2016 By Kelefa Sanneh -

Words

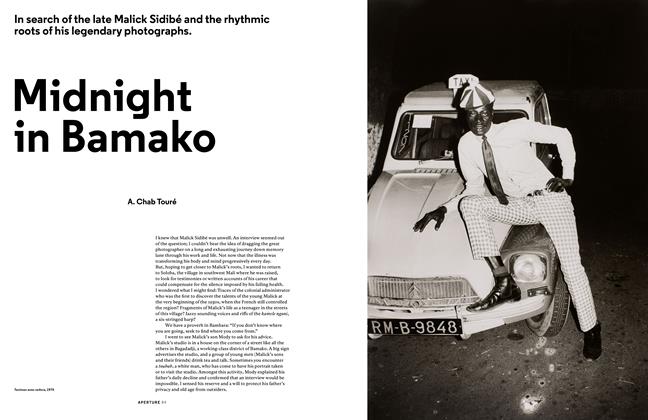

WordsMidnight In Bamako

Fall 2016 By A. Chab Touré -

Pictures

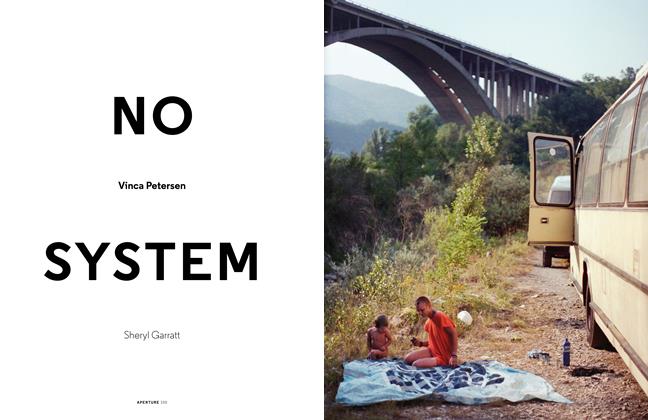

PicturesNo System Vinca Petersen

Fall 2016 By Sheryl Garratt -

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016 -

Pictures

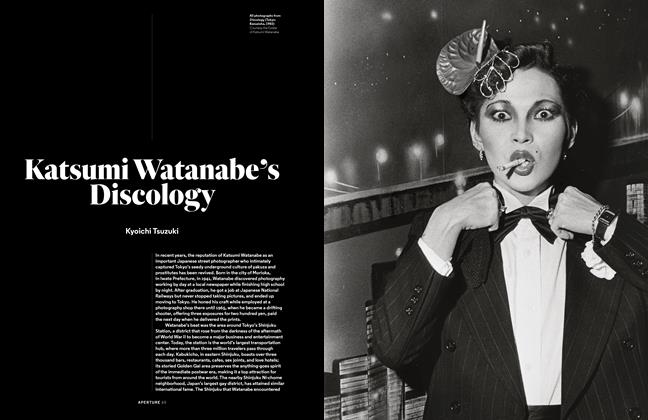

PicturesKatsumi Watanabe's Discology

Fall 2016 By Kyoichi Tsuzuki

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Words

-

Words

WordsAnnabelle Selldorf

Spring 2020 -

Words

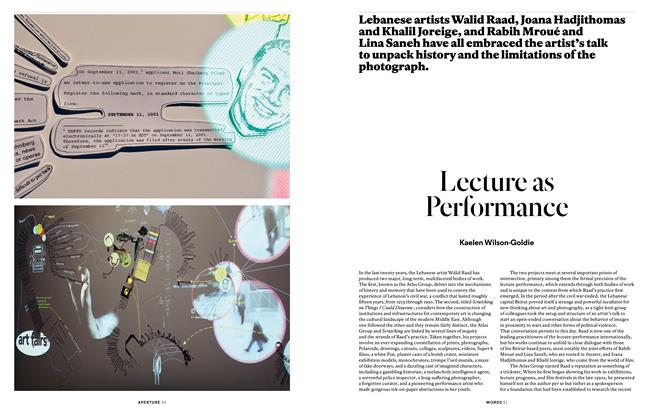

WordsLecture As Performance

Winter 2015 By Kaelen Wilson-Goldie -

Words

WordsOut Of Sheer Rage

Summer 2020 By Lauren O’Neill-Butler -

Words

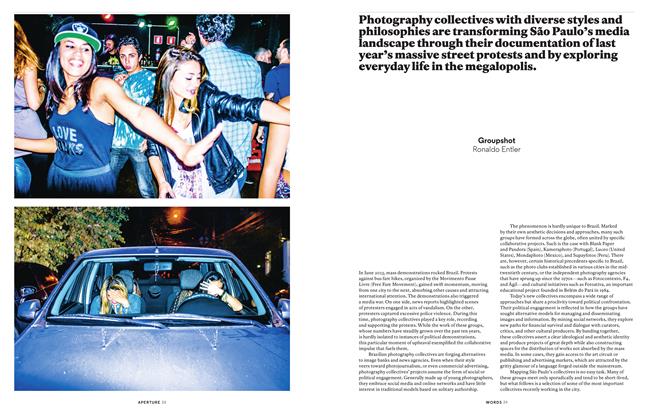

WordsGroupshot

Summer 2014 By Ronaldo Entler -

Words

WordsOpen Roads & Invisible Borders

Spring 2016 By Sean O’Toole -

Words

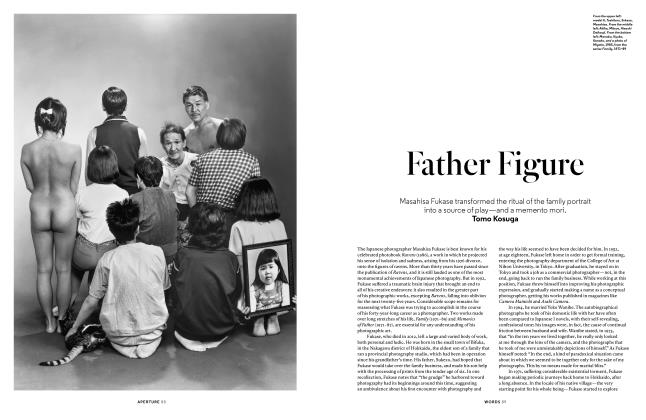

WordsFather Figure

Winter 2018 By Tomo Kosuga