Michael Schmelling YOUR BLUES

Kelefa Sanneh

PICTURES

Michael Schmelling grew up in River Forest, a near suburb of Chicago. But his first concert, in 1985, was across the state line in Merrillville, Indiana, at the Holiday Star Theatre. His older sister took him to see Corey Hart, the Canadian heartthrob known for "Sunglasses at Night.” He was ten years old, and he enjoyed the frenzy. "It was screaming girls, and this girl clawed my arm with her nails,” he says. "It was fun.” He went back to the Holiday Star not long afterward, to see Violent Femmes, the barbed Milwaukee postpunk band, having had his musical tastes permanently altered by a hip friend at summer camp who shared a cassette. "I’d never heard a song with the word fuck in it before, so it blew my mind,” he says. As a teenager, Schmelling took in shows at the big arena in Rosemont, near O’Hare Airport:

Iron Maiden, the Grateful Dead, Prince, Metallica. At the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, he earned his metalhead bona fides watching Anthrax and Exodus and Celtic Frost. These were the kinds of concerts most local kids saw, but this wasn’t, for the most part, local music. The people onstage were just passing through town.

And so when, in 2013, the Museum of Contemporary Photography asked Schmelling to spend a couple of years photographing Chicago music, he got a chance to do some of the close-up exploring he had always wanted to do. When he came to town, he stayed not with his parents in the suburbs but at an apartment in a Columbia College dorm, in the South Loop, downtown.

The assignment came in part because Schmelling had already spent time photographing music in another city: in 2010, he published Atlanta: Hip-Hop and the South, documenting an extraordinarily productive and inventive musical community.

I have known Schmelling for years, and I wrote a few words for that book, which means I got to watch him as he lurked, welcome but unnoticed, in the corners of a claustrophobic teen dance party that seemed to have been organized with no input from the fire department or any other municipal authority. That book was, in part, Schmelling’s response to the challenge posed by the place itself: How do you picture an inclusive, ever mutating scene in a decentralized city like Atlanta?

For Chicago, Schmelling knew he wanted to do something different. The city is known for the blues, a tradition he acknowledged only obliquely, by calling the project Your Blues (2013-14). (He borrowed the title from the Vancouver singer and songwriter known as Destroyer.) And although the city has produced stars like Kanye West, Schmelling was more interested in the stubbornness of homegrown musicians who stay home, no matter how small or big the crowds get. For an essay, he commissioned Tim Kinsella, leader of a string of strange and often revelatory Chicago bands (Cap’n Jazz, Joan of Arc, Owls, Make Believe), who described the joys and sorrows of life as a Chicago stalwart. "This same community, that’s so inspiring at twenty-five, can get to be pretty depressing,” Kinsella wrote. But he made it clear that he had never seriously considered dropping out or moving on.

Schmelling is not at all opposed to overthinking things, but he is opposed to overdetermining things. He shot the city’s hip-hop scene, which at the time was enjoying more critical and commercial attention than perhaps any in the country. But he also shot basement shows that captured the essential stuckness of punk, which looks much the way it did a decade ago, or two, or three. And he included some fugitive images bearing a curious credit line: they were taken in the early 1990s when Schmelling was a suburban high-school kid, first learning howto use a camera.

Instead of developing a singular idea about music in Chicago, Schmelling was looking for unexpected echoes and repetitions, across neighborhoods and across the decades. As he worked, he thought about who he was when he was going to those metal shows, who he is now, and who he might have become if he had never left his hometown. When he photographed people, he sometimes thought of them as alternative versions of himself—the project as a whole became a self-portrait, although a characteristically oblique one. "In some ways I feel like I didn’t completely finish it,” he says. "Part of me wants to keep working.”

Kelefa Sanneh is a staff writer for The NewYorker.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsListening For Eggleston

Fall 2016 By John Jeremiah Sullivan -

Words

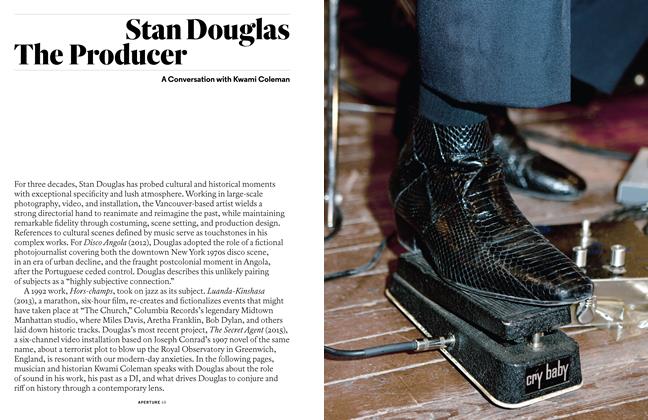

WordsStan Douglas The Producer

Fall 2016 By Kwami Coleman -

Words

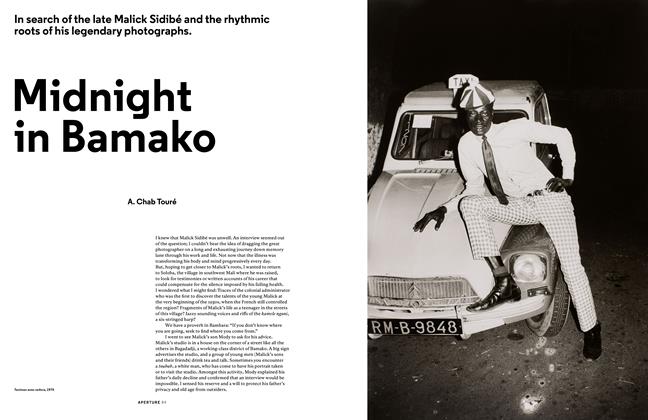

WordsMidnight In Bamako

Fall 2016 By A. Chab Touré -

Pictures

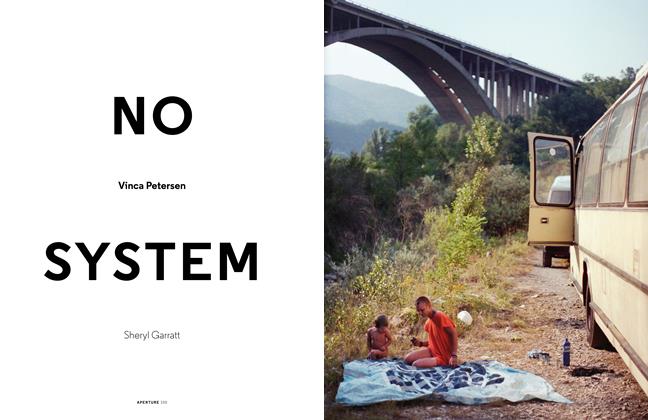

PicturesNo System Vinca Petersen

Fall 2016 By Sheryl Garratt -

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016 -

Pictures

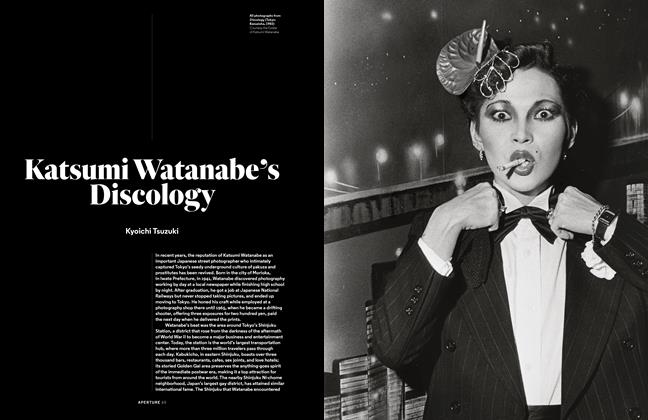

PicturesKatsumi Watanabe's Discology

Fall 2016 By Kyoichi Tsuzuki

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Pictures

-

Pictures

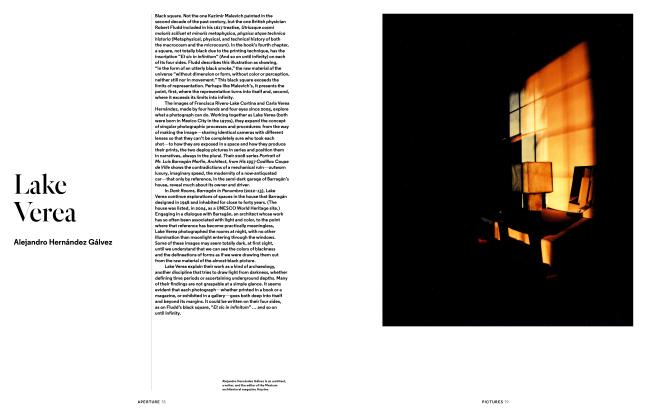

PicturesLake Verea

Fall 2019 -

Pictures

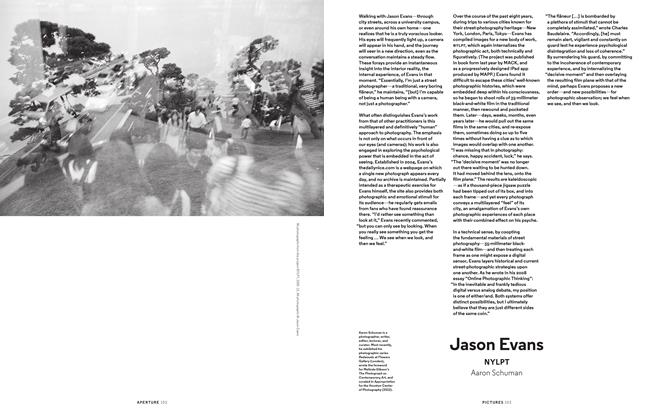

PicturesJason Evans Nylpt

Spring 2013 By Aaron Schuman -

Pictures

PicturesNatalie Czech Poems By Repetition

Winter 2014 By Drew Sawyer -

Pictures

PicturesLiz Johnson Artur

Summer 2020 By Kareem Reid -

Pictures

PicturesNelson Morales

Winter 2017 By Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes -

Pictures

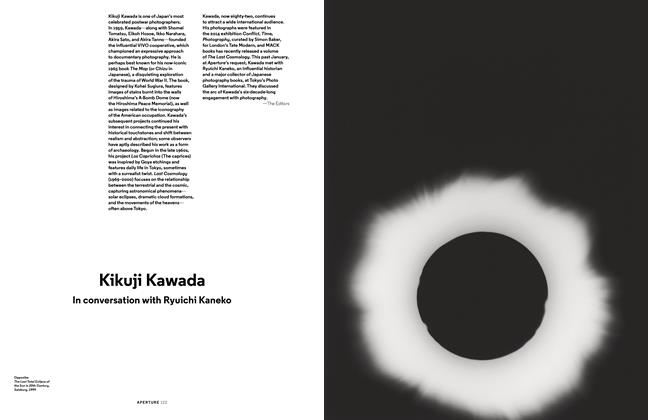

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko