Listening for Eggleston

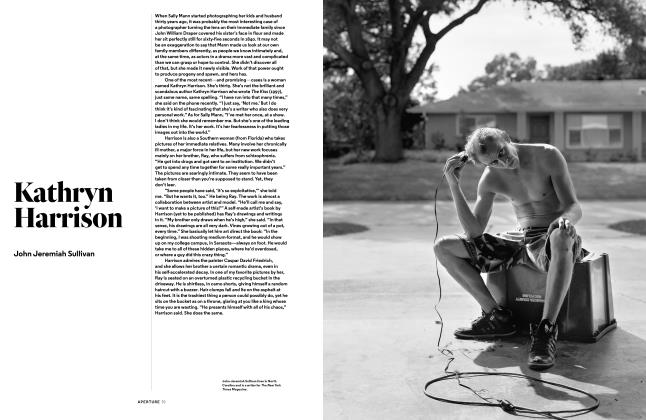

John Jeremiah Sullivan

I remember the first William Eggleston photograph I ever saw, or the first that I knew was his, that it had been made by someone called “William Eggleston”—his images have percolated up into the culture so thoroughly, I guess it’s no longer possible to be an American without experiencing a few of them, if only as album covers (Big Star’s 1974 Radio City, most notably, but there are many), and certainly for anyone with the smallest interest in American art, it’s hard to avoid the name of a man whose work most credit with having legitimized color photography as an art form. Before Eggleston, there had been a sharp divide between black-and-white and color: artists used the former, tourists used the latter. After Eggleston, or with him, everything was altered.

In 1998, when I was twenty-three, I didn’t know anything about William Eggleston. I was a few months into my first magazine job, with the Oxford American (then in Mississippi, now in Arkansas). A woman named Maude (pronounced “Maw-dee”) Schuyler Clay was helping us as a photography consultant. She’s an excellent Southern photographer herself and happens to be Eggleston’s cousin. She also said a very perceptive thing about his work, namely that he started shooting the South just at the moment it began to look more like other places. Its banality, in other words, and not its exoticism, called to him first.

WORDS

Maude came into the office one day. The magazine was doing a story on the great blues musician Mississippi Fred McDowell, and we wanted to run a memorable image of him, and probably the most memorable ever taken is one that Eggleston shot.

It shows McDowell at his own funeral, in his coffin, wearing his spotless white Mason’s apron. Maude had been able, through family connections, to borrow an original print of this picture.

I can see her carrying it through the offices. That scene in Pulp Fiction where the guy has the briefcase that glows like it’s full of magic gold? This was close to it. Every person in the office crowded around her as she pulled back the black cover of the portfolio she’d brought. The picture did, I think, literally give off light. Not gold, but pink, the pale pink of the satin around McDowell’s pinched, embalmed face. The whole corner of the art room glowed with that particular pink. I barely knew the brilliantly slashing music of Mississippi Fred McDowell at the time—I’d heard his signature “Shake ’Em On Down” and maybe one other song—but I was convinced that this photograph of his dead body was one of the most remarkable pictures my eyes had ever come up against. You knew a master had taken it, the same way that if you were to see a Caravaggio in a pawn shop one day without knowing who that painter was, you’d know it didn’t belong there, or that it belonged anywhere.

“Could you tell me about Fred McDowell’s funeral?”

I asked Eggleston in Memphis this past April. He sat in the small, light-drenched atelier of his apartment, in a building where he had lived once before, fifty years ago, on first coming to the city with his new wife, a childhood friend named Rosa Kate Dossett, a petite, pretty, dark-haired woman. They were two young, well-to-do kids from the delta. The money had given them freedom, and they brought the freedom with them to town. Not needing to make good, they set out to create themselves.

“Plantation aristocracy,” said Eggleston, making a face like the phrase smelled bad.

Bourbon and cigarettes. An endless chain of the latter, only a certain portion of the former—he’s rationed. He is seventy-six. He is debonair and still has the excellent, sculpted nose I knew from photographs. You do not want to leave him alone with your wife or girlfriend for very long.

Rosa had died barely nine months before that visit. She remained his wife all those years; they never divorced. Their domestic arrangements were unorthodox. In a nutshell, he neither hid nor apologized for his mistresses. She accepted it, or, as I believe the old-world vocabulary had it, accommodated. He performed a quick reenactment of one of their fights. She: ragingly angry about a girlfriend. He: “What do you want me to do? Do you want a divorce?” She: “How dare you mention that word around me!” (This stuff is a matter of record. When I say he didn’t hide it, I mean he really didn’t hide it. Otherwise I’d never cross the line.)

It may no longer be good feminism to say so, but I’ve known plenty of women who would put up with a lot to be married to someone as not boring as William Eggleston.

He put his hands together as if in a feeble kind of prayer.

“I miss her,” he said. He sort of whimpered, playfully but not.

I managed something barely above pleasantry: “There must have been something strong between you.”

“I can’t believe I don’t see her walking into this room right this minute!” he said.

That was him. Not abstraction. The thing.

Now he was back, after all those decades, in the hotel-like building they had shared, but alone this time. Well, without Rosa, but not alone. Students from a nearby art school were cycling in and out, mostly keeping him company, and tending to be bright,

attractive young women. The one who was there when we arrived said, “He’s my best friend.”

It was the very beginning of evening—you could slip up and call it late afternoon if not thinking—and Eggleston played the piano as he talked. A huge, gorgeous black Bösendorfer (“Chopin’s favorite,” he said). It took up most of the room.

On the wall in the other room was a portrait of Bach, the artist Eggleston mentions more than any other. It was not a poster but an oil painting, a Chinese copy of the 1740s Haussmann portrait from Leipzig.

Eggleston wore a beautiful midnight-blue cotton suit and a red bow tie, which was untied, not sloppily but deliberately, even pointedly. The silk was crisp, and one side was pulled down lower than the other. I wondered, Was it an affectation (i.e., an idiosyncrasy)? Or was there a tradition I’d never heard of, or run into, of wearing one’s bow tie this way, not at the end of the night, when any person might be photographed dishabille, but in daylight hours, boldly? I called the people at GQ—I used to work for them, I still have friends there. I asked about it.

Was this a thing, or was it just Eggleston? Just Eggleston, right? No, it was a thing. Jim Nelson, the editor of the magazine, emailed back at once, and did not dishonor his office. “There is indeed a tradition,” he wrote, “mostly embraced by flamboyant Italian tycoons with zero fucks to give. I think of the late, great Fiat billionaire Gianni Agnelli, who routinely wore his wristwatches outside his sleeve, the blades of his ties longer in the back, or hiking boots or loafers with suits.” Nelson described the style as “rebellion within a frame.” The magazine’s in-house style guru, Mark Anthony Green, answered too, and made a simple but deep observation: the bow tie wasn’t really untied.

“It’s tied,” he said. “Just not in a bow.” I looked at a picture.

He was right; the two lengths were crossed over and made into a half knot. Possible translation: I know the rules, but am confident enough to break them. Alternate translation: whimsy.

Southerners who have money won’t usually talk about money, unless they only recently got hold of it, is my experience. And when I said something to Eggleston along the lines of, “You were lucky,” he was quick to stop me. “I want to be clear about something,” he said. “The artist... if the thing is in that person to do, it will find a way out. Doesn’t matter where you plant it.” What mattered was (marvelous phrase) “inner wanting.”

True and not, I thought. True to an extent. Maybe true.

There is, however, a way quite apart from all that in which his wealth—his means, let us say—played a role in the evolution of his art, and not socially but technically. Simply put, he could afford to have his pictures printed well enough that the colors even mattered. The story is often told of how he discovered the dye-transfer process in a print shop, glimpsing commercial advertisements and noticing that their colors were much more vibrant and saturated than anything he had seen applied to his own color photographs. He had the thought, Why not use that process for my own stuff? His genius helped him ask the question, but so did the fact that he could afford to handle the answer. The result involved pictures such as his famous Red Ceiling (1973), where the blood color of the print has an almost troubling purity, as if it were still wet. Eggleston had solved a problem that was recognized by photography critics at the time. A piece that ran in the Milwaukee Sentinel in the late 1970s, a review of an early group show he participated in, said that “color photography has long been regarded as throwaway art, since, at least until recently, no color prints could be counted on to last more than a few years without serious deterioration.”

It may go without saying that any rich freak who’d been dabbling in color photography could have paid for the dye-transfer. It was Eggleston’s eye that made the pictures undeniable.

The color helped him realize and fix his vision. Critics noticed that part early on too, not the color, that is, but the vision.

In fact it’s interesting to go back and read through the early reviews of that first, notorious show at the Museum of Modern Art in 1976. The story goes that the show was hated. And those nasty reviews do exist, you can read them. But they came almost exclusively from New York City. In New York you had enough people who’d been arguing long enough about art photography to have developed a sensibility about it, but also sensibility’s evil twin, snobbishness. Because they thought they knew what an art photograph was, they knew it wasn’t like Eggleston’s pictures. “Terrible,” said the syndicated Norman Nadel at the New York World-Telegram. “Boring,” said Hilton Kramer in the New York Times.

But in the provinces? Or out west? Or even in other parts of the state of New York? The reaction to the show, and to Eggleston’s work in those years, was very different. Not knowing that all art pictures should be in black-and-white, critics there were not distracted by the shock of the color. They looked at the pictures, and the pictures were what they are. Haunting, austere, extraordinary. The Democrat and Chronicle in Rochester, New York, blared the headline, “Color photography as art—Eggleston paves way.” The Los Angeles Times said that Eggleston’s work “welds color and meaning,” the Milwaukee Sentinel that he had earned a place “in the traditions of the Ashcan School painters and the great photographer Walker Evans,” the Age in Melbourne, Australia (!) that he was “the Atget of the 1970s,” and the Washington Post (my favorite, the purest) that his work was “funny and ugly, sly and beautiful,” with “perspectives that are either weird or heroic.”

I had promised my brother, a disc jockey and pop historian, that I would ask Eggleston about Big Star, the band. Eggleston

I barely knew the music of Fred McDowell at the time, but I was convinced that this photograph was one of the most remarkable pictures my eyes had ever come up against.

said he had listened to their music a couple of times but thought it “mostly trash.” (A generational thing, I figured, maybe self-soothingly.) He did, however, like that first song of Alex Chilton’s, the one about the letter.

“You mean ‘The Letter’?”

“Yes,” he said, “that one was very good.”

Eggleston had known Alex Chilton since Chilton was a boy, having been a friend of the singer’s parents, Sidney and Mary. Sidney was a jazz pianist. Their friendship revolved around music. “I was so sad when I heard Alex had died,” he said. “In the middle of mowing the lawn!”

I asked again about Fred McDowell’s funeral, in Como, Mississippi. What did he remember about it?

“The funeral meant nothing to me,” he said, “apart from that Fred was dead.”

“How did you get to know him?”

“Through my old friend Vernon Richards. We knocked on his front door in Como, Mississippi. We were gonna do some film of him. In the daytime, he worked at Stuckey’s pumping gas.” They had shot some film. “It was lost,” Eggleston said. Footage of McDowell playing his guitar. “Wandering,” Eggleston remembered, “then, surges of melody.”

And what about the picture itself, the one I had seen?

How was it made?

“I wandered into the room where they had the coffin,” he answered. “The proprietors came up. I said, T just want a picture of Fred, my friend.’”

He had said that the funeral meant nothing, but there is at least one other picture from that day. It shows him watching the service from the back of the church. He looks over a young woman’s shoulder, and she looks back over her shoulder at him, wondering what he’s doing, for any number of reasons. At the

front of the church we see the men in white gloves who will bear McDowell’s body to the grave. There’s a triangular pinging around of gazes inside the frame, of life and death.

Eggleston became very passionate on the subject of Southern Baptists. “If I were a Nazi,” he said, “and I’m not, I’d run them out.”

“Horror, terror, evil,” he said. “The most full-of-shit institution I’ve ever imagined.”

Had he grown up going to a Baptist church?

“Until I was about six,” he said.

It was more what it did to people, I gathered, the withering ofhorizons.

He played several of his piano pieces. They were deconstructions of well-known songs, but changed enough to become original compositions, if he had wanted to call them that. But he called out the tunes. “This is ‘Stella by Starlight’,” he said.

“One of my mama’s favorite songs.” He is self-taught but plays beautifully, dramatically. It was genuinely interesting to follow him through the songs. I suppose if you get that good at one art form, you’re not going to mess with another unless you can do it fairly well; there’d be no joy in it. Like Michael Jordan’s golf career. There is a high dilettantism of those who have nothing to prove. Reportedly, the Chicago record label Secretly Canadian was working on putting out an album of his songs, but there were technical difficulties, and the project has been canceled. Many pieces exist only on old floppy discs—Eggleston was playing one of those 1980s keyboards that took floppy discs— and some were unreadable. The same question of preservation format that had given his photography a leap forward had worked to erase the songs. It was the kind of thought that, if I had said it out loud, he would have ignored, refused to answer other than gnomically, answered sideways.

He asked me to pull down the new boxed set of his Democratic Forest (2015). Ten volumes. Paging through it, I stopped at certain pictures. He leaned forward and, with his finger, traced lines of composition. Boxes and Xs. Forcing me to pay attention to the original paying of attention. “Either everything works, or nothing works,” he said about one picture, a shot of an aquamarine bus pulling into a silvery station. “In this picture, everything works.”

I made the comment that Memphis had been his muse for many decades. Was it still? Did the city still call to him?

“It is always changing,” he said. “Always.”

When it got late, I left and went looking for food. My wife had joined us by then. I did leave my wife with him. He behaved, mainly. He pulled the “How did he end up withyouV move, a line I’m used to—my wife is a tall Cuban American woman and quite bodacious. I am increasingly lumpen and huge foreheaded. But whatever. I own it. Anyway I would have been insulted if he hadn’t tried. And it meant that Mariana got to witness the most beautiful moment of the evening. I call it that without having seen it. I loved just hearing about it. He’d played “As Time Goes By” for her, “but,” she said, “full of darkness.” Right before he played it, he put his fingertips on the keys and looked up at the ceiling and closed his eyes and whispered, “Courage.”

When we were leaving, he said, “Thank you for remembering the darkness.”

John Jeremiah Sullivan is a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and the southern editor of The Paris Review.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesMichael Schmelling Your Blues

Fall 2016 By Kelefa Sanneh -

Words

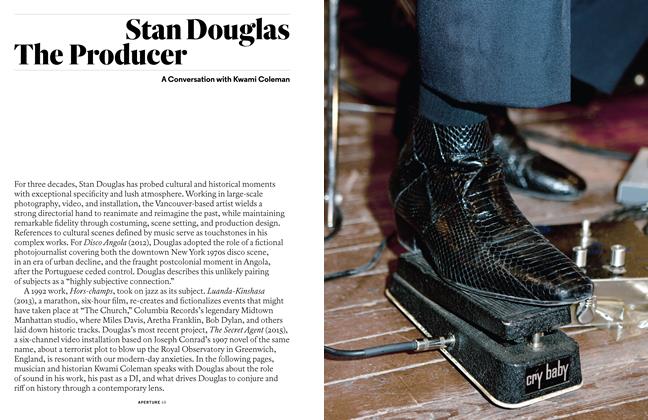

WordsStan Douglas The Producer

Fall 2016 By Kwami Coleman -

Words

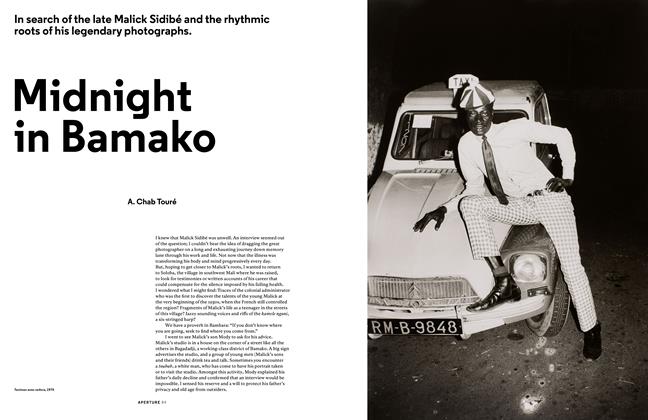

WordsMidnight In Bamako

Fall 2016 By A. Chab Touré -

Pictures

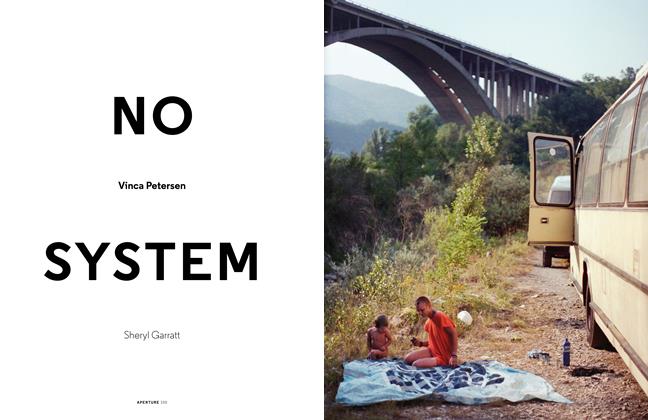

PicturesNo System Vinca Petersen

Fall 2016 By Sheryl Garratt -

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016 -

Pictures

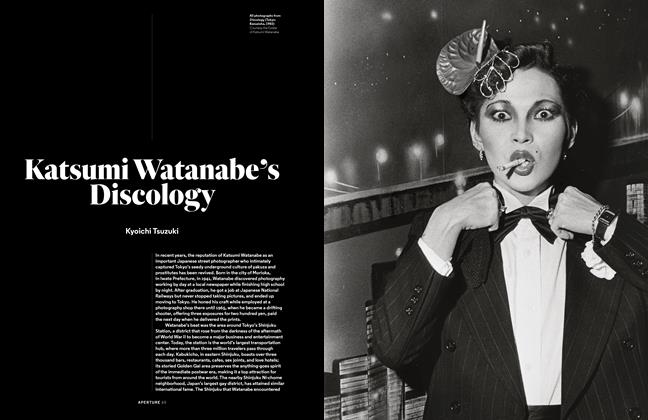

PicturesKatsumi Watanabe's Discology

Fall 2016 By Kyoichi Tsuzuki

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

John Jeremiah Sullivan

Words

-

Words

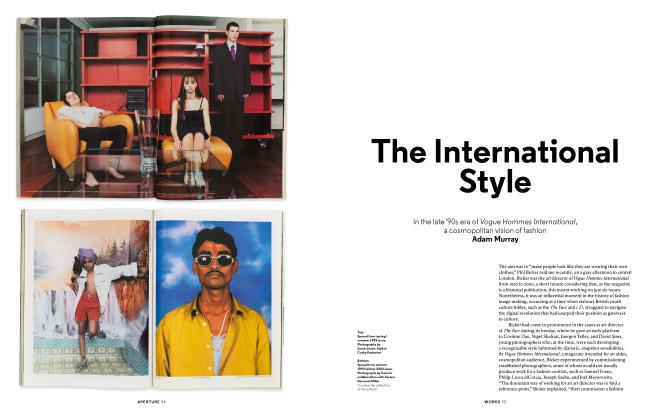

WordsThe International Style

Fall 2017 By Adam Murray -

Words

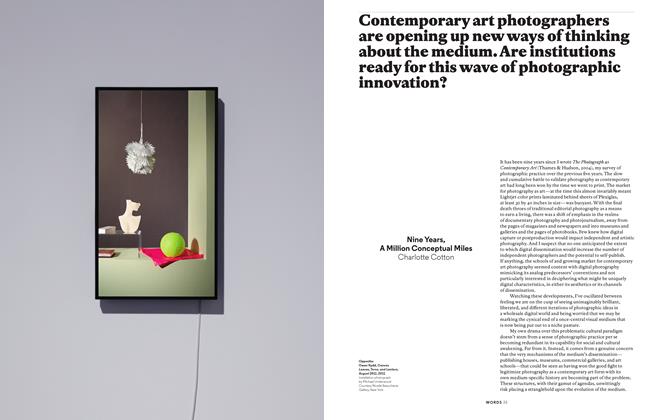

WordsNine Years, A Million Conceptual Miles

Spring 2013 By Charlotte Cotton -

Words

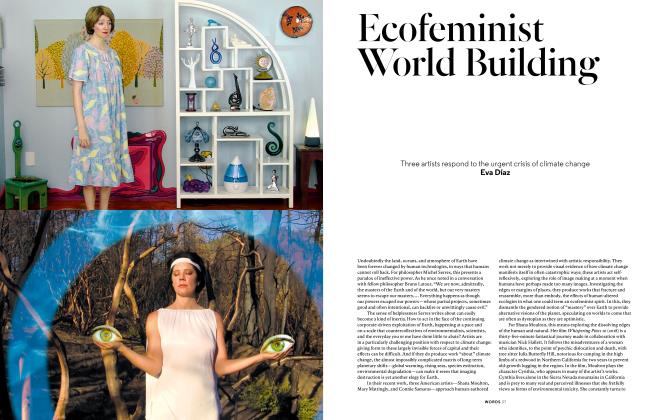

WordsEcofeminist World Building

Spring 2019 By Eva Díaz -

Words

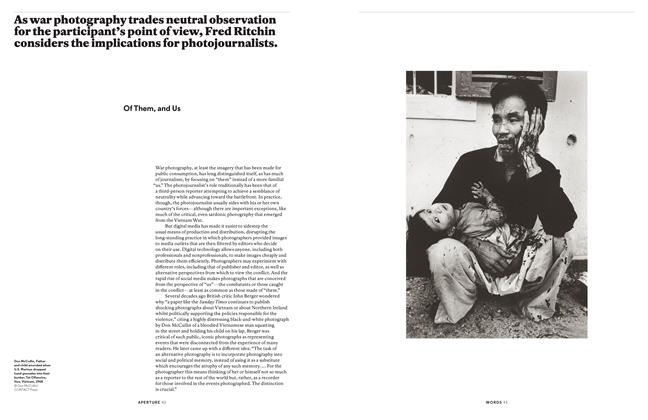

WordsOf Them, And Us

Spring 2014 By Fred Ritchin -

Words

WordsOn Record

Winter 2015 By Roselee Goldberg, Roxana Marcoci -

Words

WordsSudanese Photographers Group

Summer 2017 By Serubiri Moses