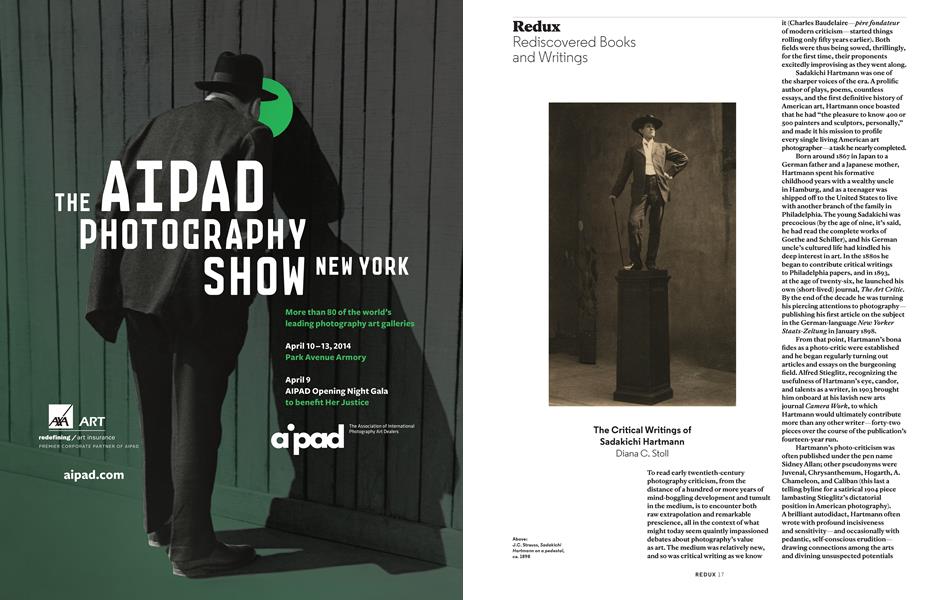

The Critical Writings of Sadakichi Hartmann

Redux

Rediscovered Books and Writings

Diana C. Stoll

To read early twentieth-century photography criticism, from the distance of a hundred or more years of mind-boggling development and tumult in the medium, is to encounter both raw extrapolation and remarkable prescience, all in the context of what might today seem quaintly impassioned debates about photography’s value as art. The medium was relatively new, and so was critical writing as we know it (Charles Baudelaire—père fondateur of modern criticism—started things rolling only fifty years earlier). Both fields were thus being sowed, thrillingly, for the first time, their proponents excitedly improvising as they went along.

Sadakichi Hartmann was one of the sharper voices of the era. A prolific author of plays, poems, countless essays, and the first definitive history of American art, Hartmann once boasted that he had “the pleasure to know 400 or 500 painters and sculptors, personally,” and made it his mission to profile every single living American art photographer—a task he nearly completed.

Born around 1867 in Japan to a German father and a Japanese mother, Hartmann spent his formative childhood years with a wealthy uncle in Hamburg, and as a teenager was shipped off to the United States to live with another branch of the family in Philadelphia. The young Sadakichi was precocious (by the age of nine, it’s said, he had read the complete works of Goethe and Schiller), and his German uncle’s cultured life had kindled his deep interest in art. In the 1880s he began to contribute critical writings to Philadelphia papers, and in 1893, at the age of twenty-six, he launched his own (short-lived) journal, The Art Critic. By the end of the decade he was turning his piercing attentions to photography— publishing his first article on the subject in the German-language New Yorker Staats-Zeitung in January 1898.

From that point, Hartmann’s bona fides as a photo-critic were established and he began regularly turning out articles and essays on the burgeoning field. Alfred Stieglitz, recognizing the usefulness of Hartmann’s eye, candor, and talents as a writer, in 1903 brought him onboard at his lavish new arts journal Camera Work, to which Hartmann would ultimately contribute more than any other writer—forty-two pieces over the course of the publication’s fourteen-year run.

Hartmann’s photo-criticism was often published under the pen name Sidney Allan; other pseudonyms were Juvenal, Chrysanthemum, Hogarth, A. Chameleon, and Caliban (this last a telling byline for a satirical 1904 piece lambasting Stieglitz’s dictatorial position in American photography). A brilliant autodidact, Hartmann often wrote with profound incisiveness and sensitivity—and occasionally with pedantic, self-conscious erudition— drawing connections among the arts and divining unsuspected potentials in his subjects, among them Zaida Ben-Yusuf, Joseph Byron, F. Holland Day, Arnold Genthe, and a host of others. He wrote and wrote and wrote, for Camera Work and other journals, sometimes cutting and pasting ideas from his own work in his haste to produce as "Sidney Allan’s” reputation as a critic and lecturer grew.

As Stieglitz understood, Hartmann was happy to dispense with bland amiability in favor of critical integrity and was not above taking the occasional potshot. In one early review, Hartmann noted scathingly that the photographs hanging at the National Academy of Design made an "adequate backdrop to the asters, grapes, and pumpkins” in the galleries, and went on to lavish attention on the frames in which the images were set. Of Gertrude Käsebier, he observed in 1900: "Her sympathies are entirely restricted to a certain artistic atmosphere which she has created in her studio, and into which every sitter, no matter how eager for actual, immediate reality he may be, is forced when he wants a picture.”

Alvin Langdon Coburn fared no better: "Whether these ghostlike apparitions have any permanent place in portraiture, I do not dare to decide. There is rarely an excuse for their existence.” And this backhanded sting for Joseph Keiley (a Camera Work colleague, with whom Hartmann frequently traded barbs):

"I have seen few men represent Nothing as interestingly.”

The best critics are able to intelligently negotiate a keen line between approbation and condemnation. In Edward Steichen’s nudes, Hartmann observes both strengths and defects: "[They] are not as perfect as the majority of his portraits, but they contain perhaps the best and noblest aspirations of his artistic nature. They are absolutely incomprehensible to the crowd... a strange procession of female forms, naïve, non-moral, almost sexless, with shy, furtive movements...imbued with some mystic meaning.”

Inevitably, in reading Hartmann’s writings we come up against the primordiality of his moment in the history of photography: pre-theory, pre-irony, pre-skepticism, though by no means pre-complications. Of the storms surrounding the Photo-Secession: "Why, then, all this mockery, noise, and opposition? Because it is a fight, after all. It is a fight of modern ideas against tradition.” He notes of Edward S. Curtis’s visual chronicles of Native Americans: "I believe it is safe to say that [this] work will satisfy all expectations as far as truth is concerned. It will give a truthful record of the Indian race.” Hard to imagine a critic today who would dare sweep forward the word truth with such insouciance.

Hartmann’s article "What Remains,” published in Camera Work in January 1911, poignantly reflects on the indelibility of art:

I sit at my desk and wonder how such a refined sensation of visional joy mingled with an appreciation of the mind so deep and true. ..could have ever been conjured up in this diffident commerce-sodden community.... Like the delicious odor in some mirrored cabinet that lingers indefinitelyfor y ears, this spirit [of the work] will notfade. It will. ..remain an active force.

Flamboyant, opinionated, sometimes wheedling, Hartmann was an annoyance to some: Stieglitz often lost patience with him; Edward Weston avoided him altogether. After an encounter with Hartmann at a 1928 party, Weston noted: "He is a much finer dancer than a writer”; today, a wonderful forty-six-second YouTube video shows that Hartmann was indeed light-footed.

But he set an early standard for photography criticism that we are still striving to maintain today, in our own era of deafening “mockery, noise, and opposition.” In 1900 Hartmann outlined the role of the critic thus:

"The question is simply whether the artist has something to express and expresses it well, and it is the critic’s business to tell his own impression frankly, without personal subterfuge, to his readers.”

That sounds simple enough, doesn’t it?

Diana C. Stoll, based in Asheville, North Carolina, writes frequently about art and photography, and edits books for Aperture Foundation, the Museum of Modern Art, and others.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesBasetrack

Spring 2014 By The Editors -

Pictures

PicturesMari Bastashevski State Business

Spring 2014 By Daniel C. Blight -

Pictures

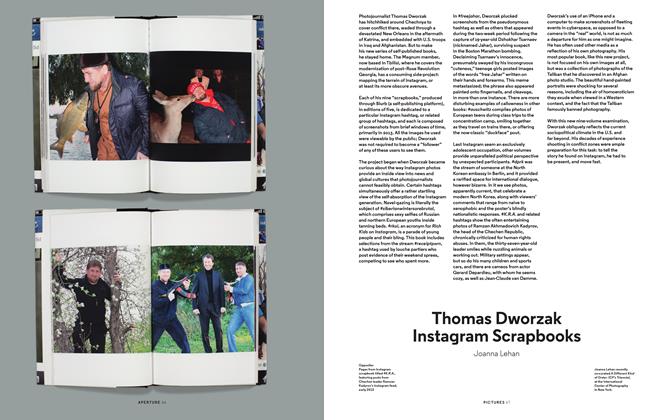

PicturesThomas Dworzak Instagram Scrapbooks

Spring 2014 By Joanna Lehan -

Pictures

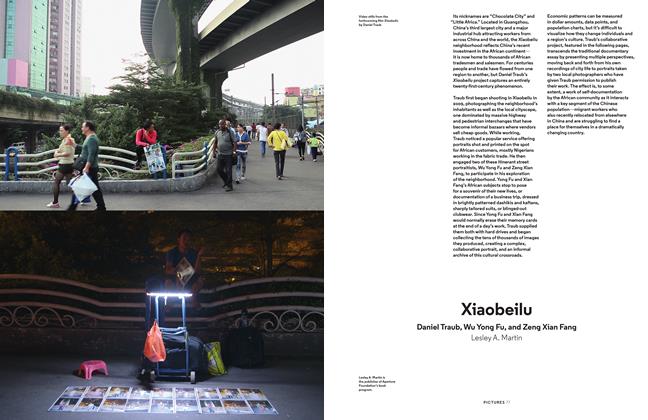

PicturesXiaobeilu

Spring 2014 By Lesley A. Martin -

Pictures

PicturesWe're Talking About Life And Culture

Spring 2014 By Wendy Ewald, Eric Gottesman -

Pictures

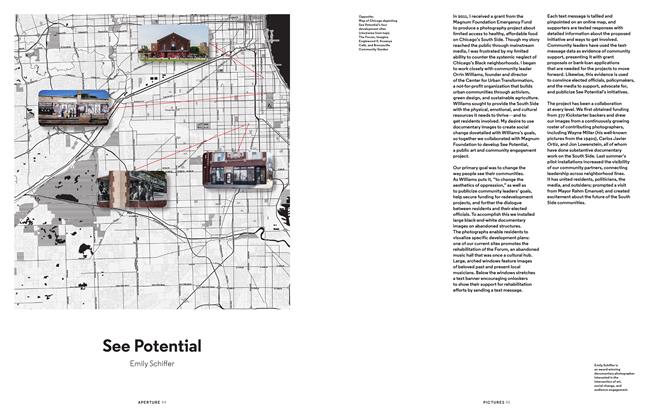

PicturesSee Potential

Spring 2014 By Emily Schiffer

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Diana C. Stoll

-

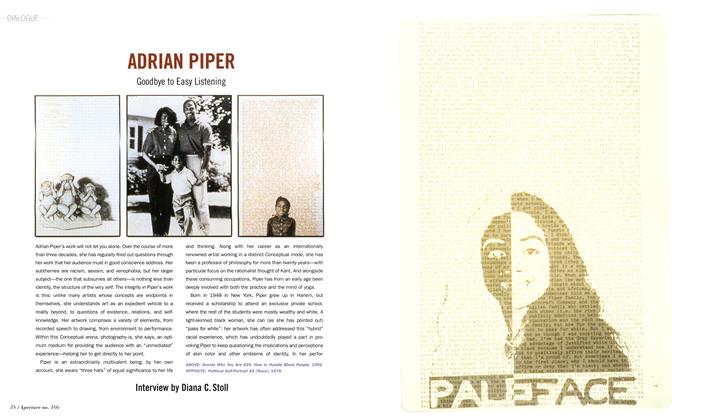

Dialogue

DialogueAdrian Piper

Spring 2002 By Diana C. Stoll -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessLoretta Lux's Changelings

Spring 2004 By Diana C. Stoll -

Profile

ProfileElinor Carucci’s Theater Of Intimacy

Spring 2006 By Diana C. Stoll -

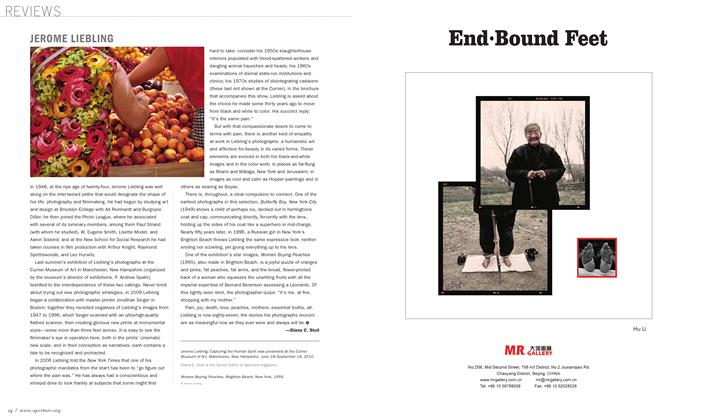

Reviews

ReviewsJerome Liebling

Summer 2011 By Diana C. Stoll -

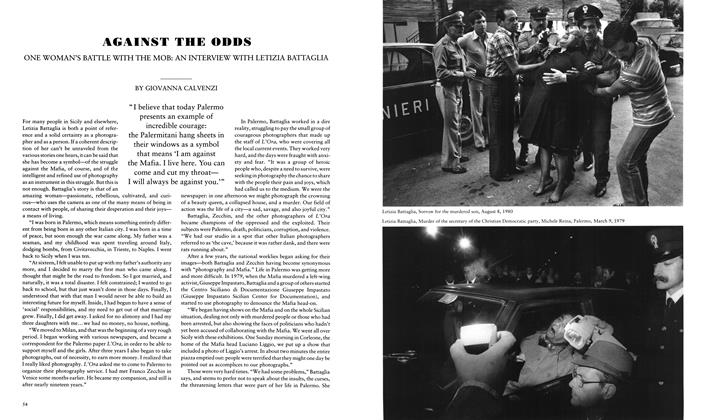

Against The Odds

Summer 1993 By Giovanna Calvenzi -

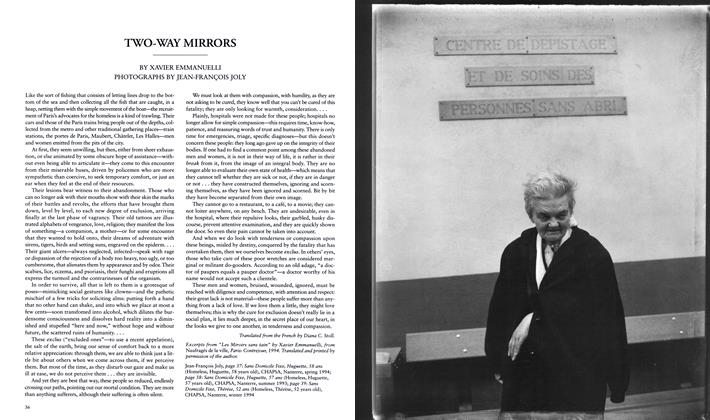

Two-Way Mirrors

Winter 1996 By Xavier Emmanuelli

Redux

-

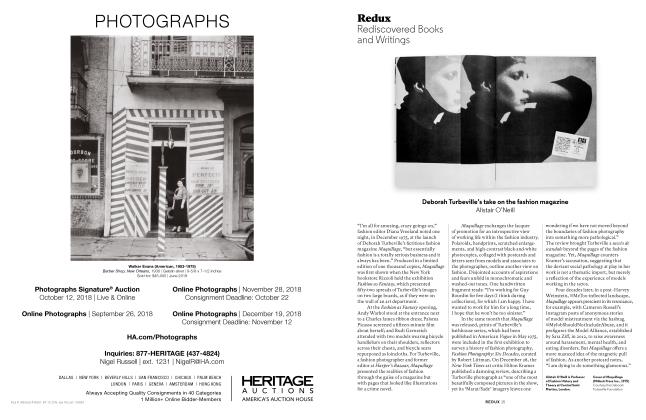

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2018 By Alistair O’Neill -

Redux

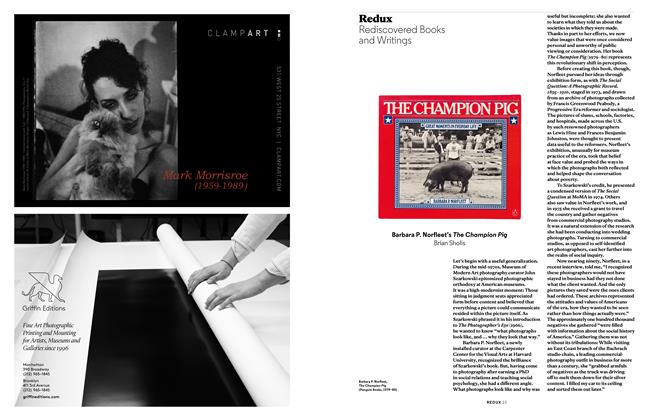

ReduxBarbara P. Norfleet's The Champion Pig

Spring 2015 By Brian Sholis -

Redux

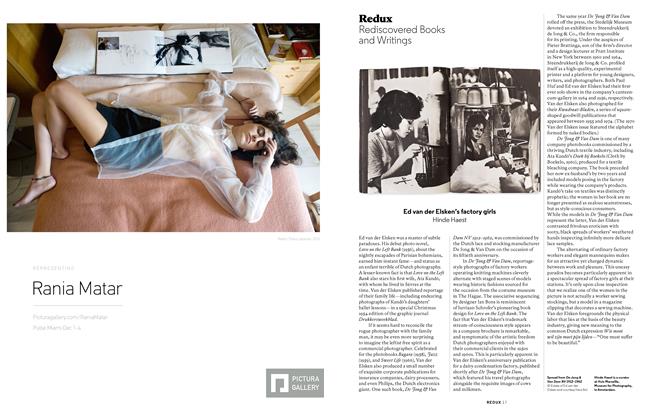

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2016 By Hinde Haest -

Redux

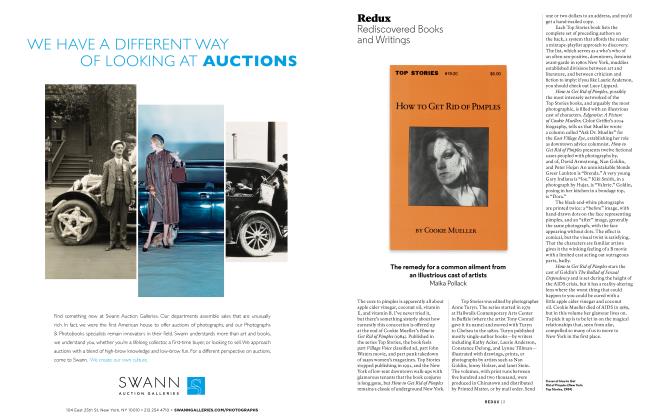

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Winter 2017 By Maika Pollack -

Redux

ReduxThe Extended Document

Fall 2014 By Mary Statzer -

Redux

ReduxIn Our Terribleness

Winter 2013 By Vince Aletti