SNOWMAN

ARCHIVE

w.m.hunt

THE PHOTOGRAPHS OF WILSON A. BENTLEY

The story of Wilson A. "Snowflake" Bentley has echoes of "Jack and the Beanstalk": to the mystification of his dairy-farming parents in northern Vermont, the teenage Bentley, in effect, traded in the cow for a view camera—and found his happy ending in the form of a lifetime of photography and discovery.

Born in 1865, Bentley lived and worked until 1931. Over the course of his career, he systematically demonstrated that each snowflake is unique, and that all are dendricular (six-pointed). Bentley worked tirelessly to promote his work in the scientific community; he lectured frequently with remarkable lantern slides, contributed articles on his findings to various technical journals, and left a legacy of glass-plate negatives and papers to the Buffalo Museum of Science in upstate New York.

But it is the beauty of Bentley’s work that merits critical recognition today. His images are jewels: faceted, spiky, lacy, and graphic. They are matrices of light and shadow, each snowflake diligently captured, magnified, photographed, and meticulously printed.

Bentley’s route to his place in the history of photography has been somewhat roundabout. He is a hero of his Vermont hometown of Jericho, where the small historical society maintains an impressive website (www.snowflakebentley.com) and a quarterly newsletter on him, and produces annual editions of contemporary Bentley prints. Many young people know of “Snowflake” Bentley as the subject of the Caldecott Award-winning children’s book Snowflake Man, by Jacqueline Briggs Martin. Quilters are familiar with his images from another book, Snow Crystals, by Bentley and William Humphries. A biography, The Snowflake Man: A Biography of Wilson A. Bentley by Duncan C. Blanchard, was published in 1998. Last holiday season, shoppers at New York’s Saks Fifth Avenue brought home their purchases in distinctive shopping bags with Bentley’s snowflake photographic images used as the design motif.

It’s entirely possible that this article is the first on Bentley to appear in a mainstream photography publication. Apart from a handful of gallery exhibitions, his photographic work has been largely out of the public eye. This may have more to do with supply than demand: despite the small clutch of collectors scrambling to find vintage material, there is simply not much available. In a way, his case is analogous to that of Eadweard Muybridge and his 1887 “Human and Animal Locomotion” series. Both men were making what they felt were scientific, representational documents—which today have been recontextualized as desirable and collectible art objects. But while there are thousands of good, affordable Muybridge prints available for collection, with Bentley—unless there is some mother lode yet to be revealed—there are relatively few vintage prints in circulation.

Bentley, especially as a younger man, was the quintessential “outsider” artist, making work for the sheer exhilaration and intensity of it, with no instruction or critical support, just singleminded purpose. In contrast to better-known “self-taught” photobased artists such as Eugene Von Bruenchenhein or Morton Bartlett, Bentley made work that is straightforward and singularly beautiful: obsessive, but not pathologically so. Still, his status as “outsider” has set him apart from the photographic pantheon. Happily, we seem to be experiencing a rethinking of the photographic canon today. Critics, curators, dealers, and collectors are now looking at the totality of photography; vernacular and commercial works are the subject of fresh interest.

Contemporary audiences for Bentley’s work may also find a spiritual component in its ascetic purity. The individual images are simply luminous. It is a lovely irony that if Minor White and Walter Chappell and others of their ilk had known of this work, they might have aimed their search for transcendence in a more objective direction.

One wonders: aesthetically and creatively, what references might Bentley himself have had? Did the exact and perfect beauty of Vermont in the winter inspire him? Snow. Inuits are said to have a hundred words for it. How many do they have for beauty? Bentley expressed both uniquely. Like his nickname, “Snowflake,” he was truly one of a kind, an American original.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

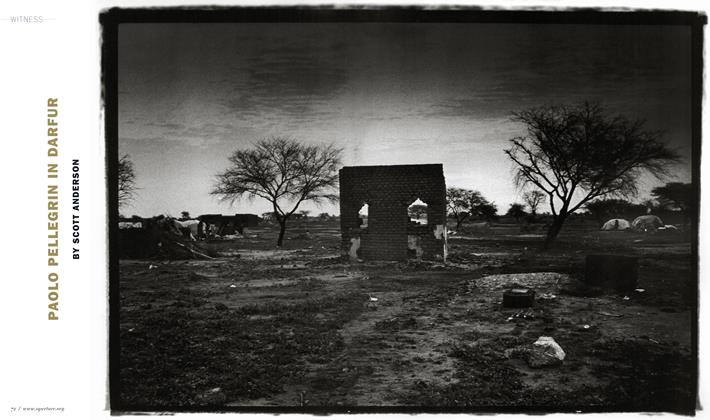

Witness

WitnessPaolo Pellegrin In Darfur

Spring 2006 By Scott Anderson -

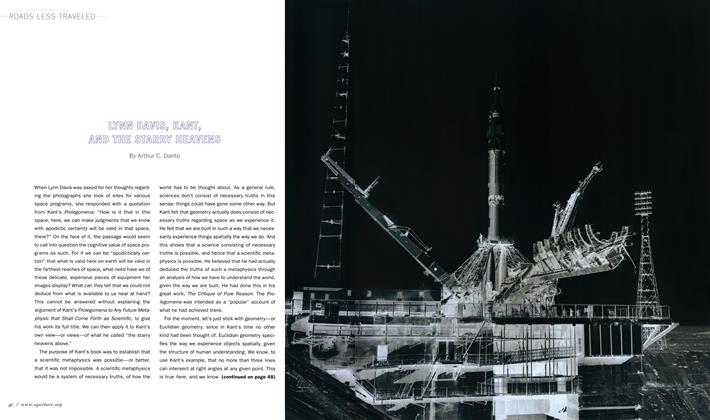

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledLynn Davis, Kant, And The Starry Heavens

Spring 2006 By Arthur C. Danto -

Profile

ProfileElinor Carucci’s Theater Of Intimacy

Spring 2006 By Diana C. Stoll -

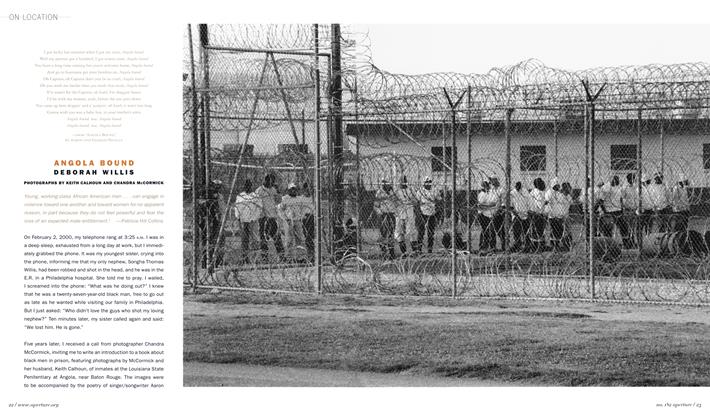

On Location

On LocationAngola Bound

Spring 2006 By Deborah Willis -

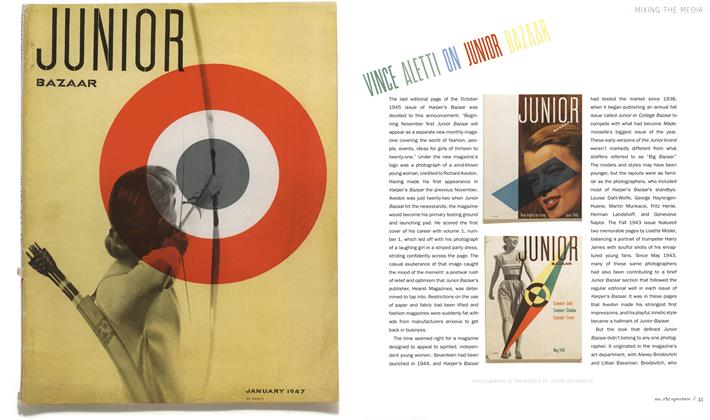

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaJunior Bazaar

Spring 2006 By Vince Aletti -

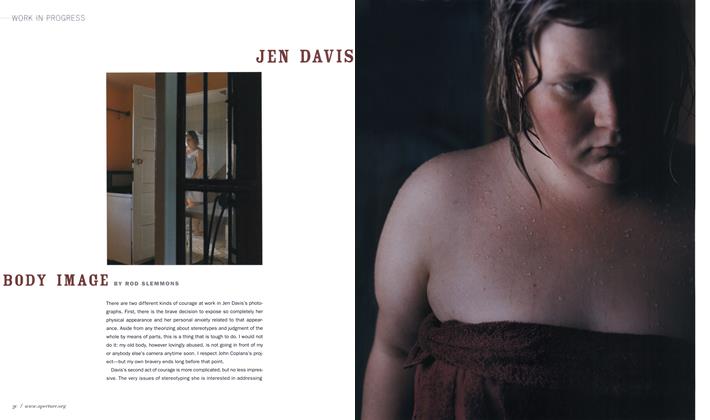

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressJen Davis Body Image

Spring 2006 By Rod Slemmons

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Archive

-

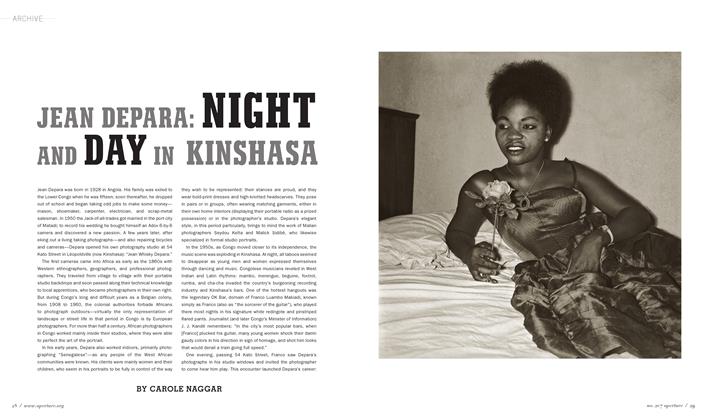

Archive

ArchiveJean Depara: Night And Day In Kinshasa

Summer 2012 By Carole Naggar -

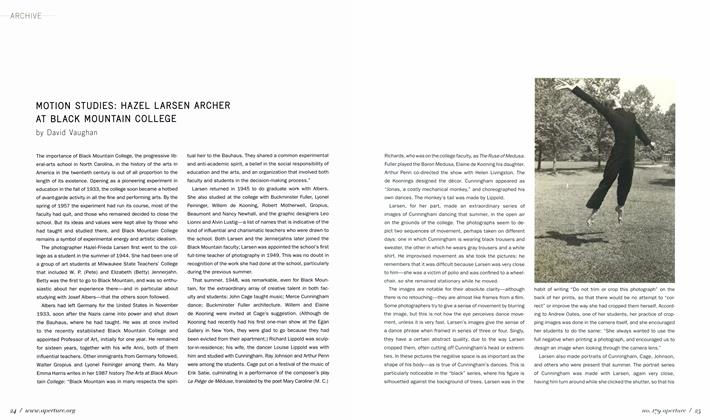

Archive

ArchiveMotion Studies: Hazel Larsen Archer At Black Mountain College

Summer 2005 By David Vaughan -

Archive

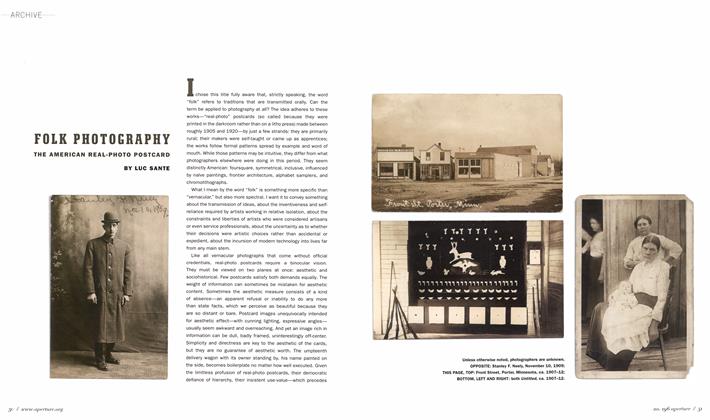

ArchiveFolk Photography The American Real-Photo Postcard

Fall 2009 By Luc Sante -

Archive

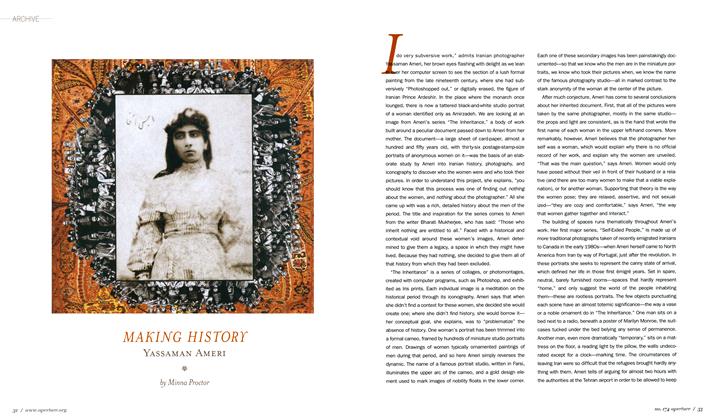

ArchiveMaking History Yassaman Ameri

Spring 2004 By Minna Proctor -

Archive

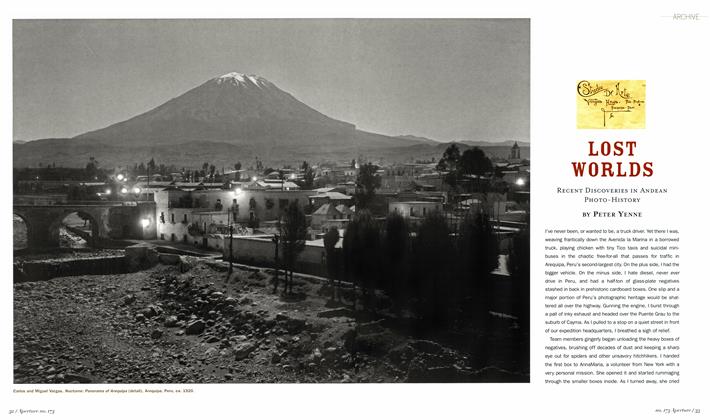

ArchiveLost Worlds

Winter 2003 By Peter Yenne -

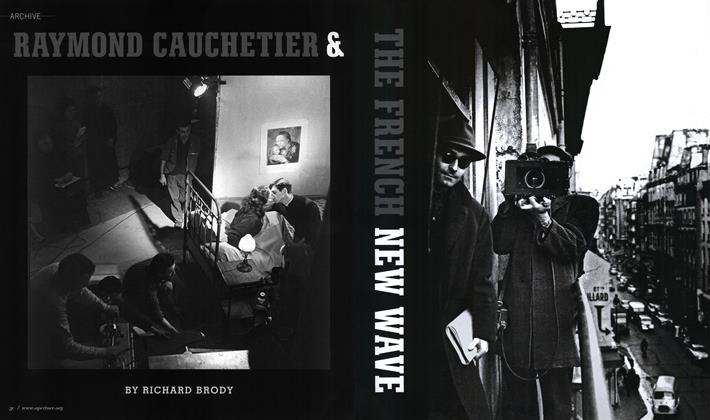

Archive

ArchiveRaymond Cauchetier & The French New Wave

Winter 2009 By Richard Brody