IN VISIBLE CITIES

ON LOCATION

MAX BLAGG

In vain, great-hearted Kublai, shall I attempt to describe Zaira, city of high bastions. I could tell you how many steps make up the streets rising like stairways, and the degree of the arcades' curves, and what kind of zinc scales cover the roofs; but I already know this would be the same as telling you nothing. The city does not consist of this, but of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past.

—Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

In Visible Cities consists of three monochromatic panels and one photograph. To make each panel I began by choosing two points in Manhattan, which would act as the frame. The titles of the pieces were chosen for places that once existed at these coordinates, but no longer exist today. I then walked between these sites and, using my phone, collected the names of all the WiFi networks that appeared on my screen along the route. I arranged the found text from each walk into grids and produced large stencils. On fourby-eight-foot aluminum panels I used acrylic paint and sprayed the ground black. Using the same pigment I then sprayed through the stencils, creating a field of names rising in low relief above the monochromatic surface. The resulting works are cameraless landscapes, invisible snapshots: representations of both the paths depicted and the moment of their recording, connecting the passage of time in the history of a city to the specific date the network names were recorded. This makes the project peculiarly photographic; the recording device has simply transformed from a camera into a phone.

—B.K.

I have always been Intrigued by the proximity of New York City’s past to its present, how it remains so tangible, despite the demolition, construction, and reconfiguration constantly taking place. I so much admired how Barney Kulok’s In Visible Cities project redefined and re-mapped these familiar landscapes that I was inspired to follow his routes and project on them my own fragmented verbal history, based on thirty years of walkabouts in and around the same urban premises.

“Starting out with a single object that will solve the crime. . . .” The gun sign Weegee photographed is long gone along with the firearms dealers it once announced. On this side street of Manhattan a man once landed on the spikes of the railings around the Police Building, tossed out by drunken cops. It didn’t even make the front page. The cops are gone to cemeteries in Queens, railings melted down for artillery shells, supermodels live here now, and across the street 400 Broome is a college dorm. In a previous life the building was an evidence locker, cluttered with drugs and weapons, the tag on a bloodstained hammer describing in clinical detail the end of a life. Massive quantities of confiscated dope from the French Connection were replaced with sugar and cornstarch. The theft was only discovered because insects were forming long lines to feed on the switched bait, by which time half the city was on the nod.

Who lives here now?

Purple Haze Jezebel luigi Extreme pubic templefong 2 Guys and a Girfriend .kikiofbroomestreet mangomama Mandalay haiku anothergreenworld freefish mrsmoustache star80 El Bordello b rasseye jackieho

Each intersection a gathering point for memory. Summon the dead who propelled you. Criminals were hanged and buried at crossroads so they would not know which road to take if they awoke. Lives in cities lost in so many ways; cut down by buses and cabs, by dagger and shotgun, knife and sword, crushed by elevators, sliced by axes, stuck with ice-picks and needles; even lightning bears down; that boy on a Village roof dancing in a storm, Thor sent the hammer, blew him out of his shoes. Guns and gunshots in Union Square. Valerie Solanas, crossing the park in that dumb newsboy hat, reread her manifesto for cutting up men, then went up to the sixth floor of 33 Union Square West and fired a .32 slug into Andy Warhol’s torso, damaging his oesophagus, gallbladder, liver, and spleen. Did Fred Hughes mess his custom-made pants when Valerie held the gun to his head? Wouldn’t you? (I peed my pants when chased by skinheads once, took me years to admit that, terrified, I bolted like a rabbit. They didn’t catch me.) Fred was spared when Valerie’s pistol jammed. Andy survived, maimed

for life. Lou Reed wrote a poem about the scars on Andy’s chest that was published in the Paris Review soon after. Light floods over the low buildings from all directions, illuminating the sanitized park where Old Methadonians used to gather on damaged benches, junk crawling through their blood like snakes. Skateboarders hit it now. At 17th Street, four cop cars equals one hundred well-dunked donuts.

A meal without mushrooms is like a day without rain.

—John Cage

In the greenmarket the dirt on the rutabagas and the celeriac was a murky black, as if they had been cultivated in industrial waste. Ruddy-cheeked farmers must explain why their spuds cost two dollars a pound, market prices adjusted to snare the yupsters sweeping through Whole Foods, waving credit cards sharp as knives. Richard Long doesn’t consider the planet overcrowded, he still finds solitary places, empty landscapes in which to wander. The light is beautiful in Union Square today, sky as blue as Mongolia’s. Or Prussian blue like an Austrian’s eyes or an Yves Klein (no relation to Klein’s where Ted Berrigan and Joe Brainard rubbed soft sweaters on their way to poetry). Filene's has moved up from the basement. At the foot of Park Avenue, cabs unload punters outside the new hotel, ten yards from where Max’s Kansas City once ruled the night, Jackie Curtis and Rene Ricard shrieking in the back room, dispensing pass and fail cards to the hip and the lame. “Candy says, I’ve come to hate my body/and all that it requires. . . .”

Everything we come across is to the point.

—John Cage

Saint Marks Place and Third Avenue, clerking at the bookshop, thinking about the Five Spot, a jazz club gone before I arrived here with nothing but Frank O’Hara's Lunch Poems in my pocket. “The Day Lady Died” explained everything about New York, then and now. East across 8th Street toward Broadway, Grace Church silvered by winter sunlight, the buildings full of academics living large, vast apartments and tenure and regular publication of books that go directly onto the university syllabus. Green eyes scan the brutalist high-rise at Mercer Street. Ana Mendieta tried to fly here, Ana couldn’t fly, Ana died. Carl Andre's influence on Richard Long cannot be underestimated.

The ley lines glitter like rivers seen from a plane. One block south Mickey Ruskin made his last stand at the Chinese Chance, now a deli serving innocent apprentices. Mickey wouldn’t give me the night shift, where the money was, where Julian Schnabel and Linda Yablonsky were flipping burgers and smashing crockery, instead I had to deal with the daytime, furious merchants waving unpaid bills, and in the late afternoon a few alcoholic painters fried by another day of trying to top Jackson Pollock, secure in the bitter knowledge that it simply couldn’t be done. The joint was smoked out by heroin eventually. Ghost traces of elegant and shabby saloons and salons, lines of blow on every flat surface, sickly glamour of the early '80s wafting in like rotten flowers.

Who lives here now?

Killyourmother sugarbush labranchina fatbooty FoHoCo WeHaveMice Thoughtpolice chow downer Auntie Christ Fallopian Jackaisass Deadted Malegaze Betelgeuse

On University Place the cobbler, an endangered species, bends to his lathe, but even he has a sideline in slightly used Chanel bags and Prada shoes. A Dawn Powell look-alike turns the corner of 11th Street, gray-haired lady going to hock her husband's Rolex at llana Fine Jewelry, established 1942. The Cedar Tavern no longer exists, where the big guys in overalls drank and fought and tore the toilet doors off their hinges, sneered at dapper Alex Katz chatting with Frank O'H., while hungry women waited in line to undress for genius. Many died too soon of drink and heart attacks, left shards of glory on the walls of the wealthy.

Up through Union Square again to 23rd Street, broad avenue running out to Western skies, while the Flatiron glides north, terracotta sails undulating in the wind as it drags Fifth Avenue and Broadway in its wake. At 26th Street and Fifth in 1989 at a nightclub called MK, we held a Viking burial for Cookie Mueller, undone at forty like so many of our crew. Saluted her with noise and tears and roses, launched the funeral boat and refilled our powdered noses. Twenty-one years now in the country of the dead.

Near Madison Square Park, a low-slung sun strikes the golden tower of the Metropolitan Life Building. Delicate skeletons of wintry trees remain in shadow. February, distant promise of spring, light gone in a minute. At the Little Church Around the Corner, someone is praying for someone to be healed. A few steps on, where the number 291 should gleam in polished brass, Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery has disappeared, the building gone, erased and raised again, “turning the inside out.”

The past? [Bucky] Fuller’s answer: keep it.. . cover it with a dome. . . .

—John Cage

At 2 Rector Street, an office cleaner murdered here a month ago, stalked and killed by a maniac, has laid her shadow on the building. Across Trinity Place, the church, surrounded by temples of commerce, doesn’t seem like it could save me. By the World Trade Center, carrion eaters earn a living from the dead by hawking pictures of 9/11, nine years on. Seven cranes are working in this massive pit, money pouring into the ground, and hovering in the air, unresolved, three thousand souls still not properly dispersed to their own Valhallas.

I feel proprietary about the Twin Towers because I was walking my daughter to school that morning, five hundred yards south of where the first plane went in. It still enrages me, that they were so close to us, to her. I’d block their path to paradise if I could. Flight 11 from Boston flew over my head so low I could see the markings on the underside and it just kept on going, too low oh God too low and entered the North Tower and disappeared in smoke and flame. The entire side of the building rippled like a pond struck by a stone . . . it was true to say I could not believe my eyes. A jetliner piercing a skyscraper like a javelin. We are supposed to look back at the past without regret, but who can dismiss the sorrow that morning brought? And the years since, the persecution and destruction of Iraq, the unnumbered dead who won’t see this blue sky today or rain tomorrow.

Can the philosophy, Sophie, and move on. Independence Plaza at Flarrison Street, ball of opium on the coffee table, the neighborhood empty as a J. G. Ballard story when we moved in, a deserted motorway to ride bikes on, Art on the Beach. Forty North Moore, a quiet blue-collar high-rise, distinguished only by a poodle plummeting from the thirtieth floor, flung by a raging boyfriend, and duly added to our compendium of defenestration. This garage on Greenwich Street used to belong to the FBI, was always filled with fake cabs, ambulances, bread trucks stuffed with recording devices to document an endless stream of witless gangsters mumbling about macaroni and cannoli. Take the cannoli. Who said that? Tony Soprano lives across the street, art imitating life, which keeps showing up. Here for instance, posed like a Helen Levitt portrait, three girls playing hooky, smoking cigarettes in the freezing street. One of them the daughter of an old friend. Last time I looked she was a tiny seal shimmering in a summer pool. . . . Crossing Desbrosses Street, Jungle Red, a salon for the ages. Red gave great haircuts, and saved small plastic packages of cut hair, like the bags strung around somebody's tomato patch in the country to keep away the deer. Across the street, a small agile beauty named Marcia documented the Mudd Club-bound mob in her night studio. Madness enough for everyone.

Who lives here now?

Wishbone Shoofly Vietcong bollocks dogkilla French kiss bitchslap Lupus rex curmudgeon puckfem gus-grissom shadrach meatshack mortimersnerd

On Canal Street a fender-bender has three drivers in a rage of cell-phone conversations, hours of paperwork ahead, arguing with insurance agents and bent mechanics. Geoff Hendricks's tiny house a museum of Fluxus beauty, Lawrence Weiner’s words inscribed across the lintel. “Water spilled from source to use.” Next door a store dedicated to cookbooks, some certainly written by Elizabeth David, who probably ate mushrooms with John Cage, or should have. Her cooking instructions are random and casual: “Take a handful of butter. . ..” She pokes fun at F. T. Marinetti’s critique of pure pasta, which makes me hungry, but this long stretch of Greenwich Street has nothing but the UPS building, flat and low, moving goods and packages day and night. Walked the saluki here in another life. He ran after cars and one finally caught him.

At Morton Street acres of new glass rise above the waterfront where lines of empty trucks once parked, animated at night by dozens of copulating bodies. . . . Peter Hujar caught the cool menace of the Lower West Side in 1977, furtive men moving in shadows, looking for a kiss as a fatal virus leapt from one to the next.

On the corner of Leroy Street, clever English lads working the art business. Smells like fresh-baked money. I warm my hands on Silke Otto-Knapp's interiors and leave. The industrious gallerists never look up from their laptops. Last block to Christopher Street is solid granite and brick, red as an Edward Hopper painting, mortar cured with the mason’s piss. Past church and school and the old post office with its curving corners, dead letters, the young and the restless pacing tasteful interiors, full to the brim with Adderall and midcentury furniture, blameless art.

Final ley line leads to Dylan Thomas, staggering from the White Horse as the El roared by, someone helped him to Saint Vincent’s, where he died. They’re tearing down that hospital too. Let the old Bohemians croak in their walk-ups. Nothing sacred, everything remembered.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Archive

ArchiveThe Last Thirty Years Of Mexico

Fall 2010 By Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, David M. J. Wood -

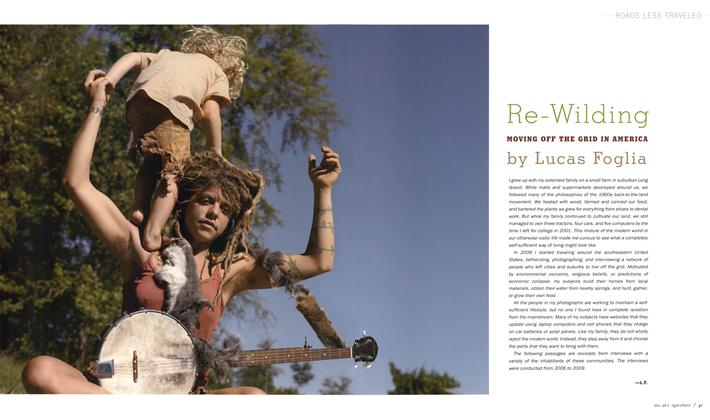

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledRe-Wilding

Fall 2010 By Lucas Foglia -

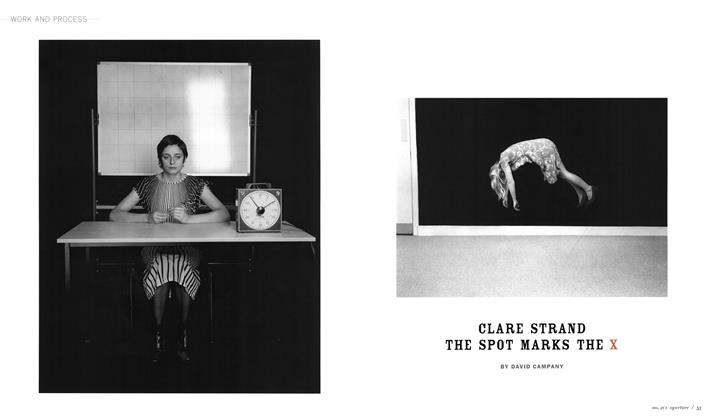

Work And Process

Work And ProcessClare Strand The Spot Marks The X

Fall 2010 By David Campany -

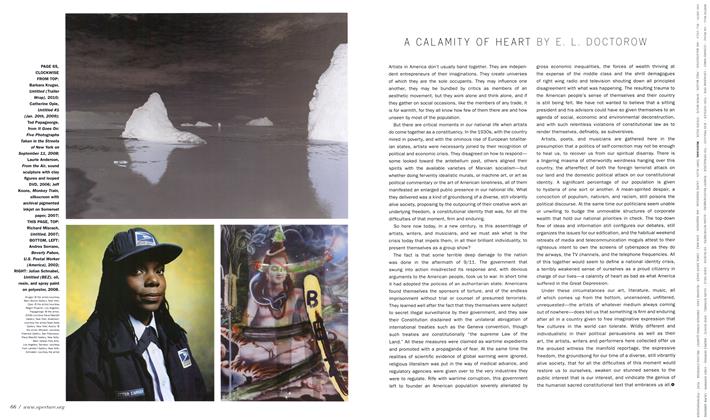

Theme And Variations

Theme And VariationsA Calamity Of Heart

Fall 2010 By E. L. Doctorow -

Witness

WitnessHeroes Of The Storm: Five Years After Katrina

Fall 2010 By Deborah Willis -

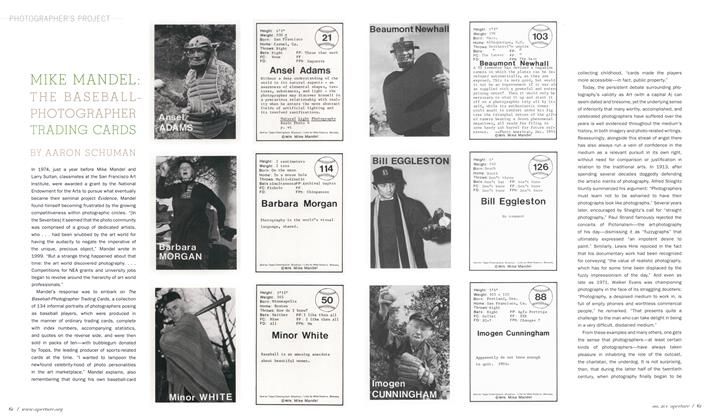

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectMike Mandel: The Baseball-Photographer Trading Cards

Fall 2010 By Aaron Schuman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Max Blagg

On Location

-

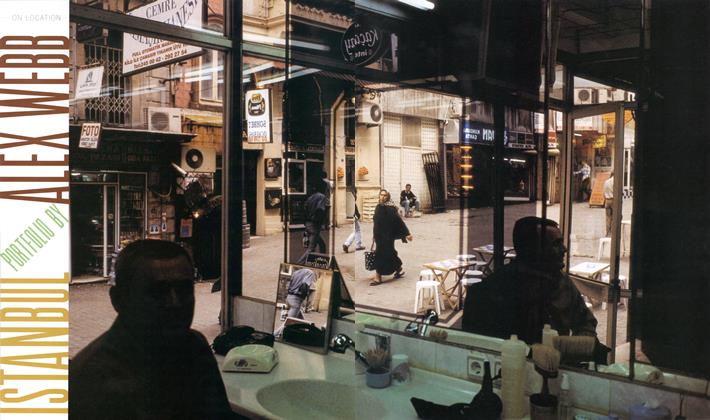

On Location

On LocationIstanbul Portfolio By Alex Webb

Winter 2005 -

On Location

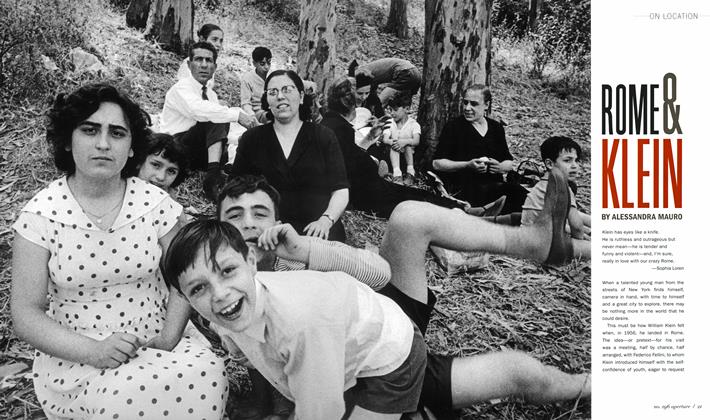

On LocationRome & Klein

Fall 2009 By Alessandra Mauro -

On Location

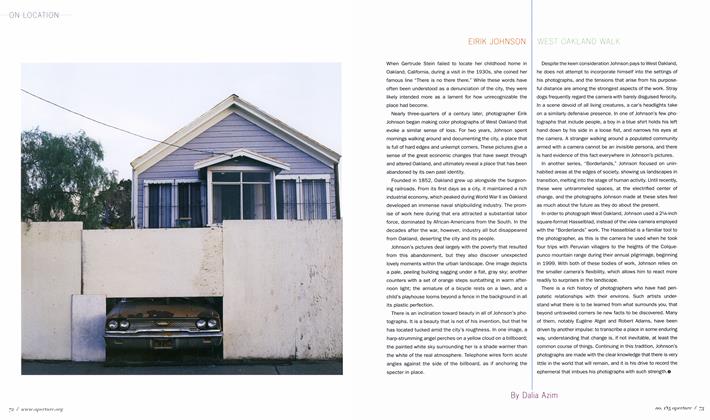

On LocationEirik Johnson West Oakland Walk

Winter 2006 By Dalia Azim -

On Location

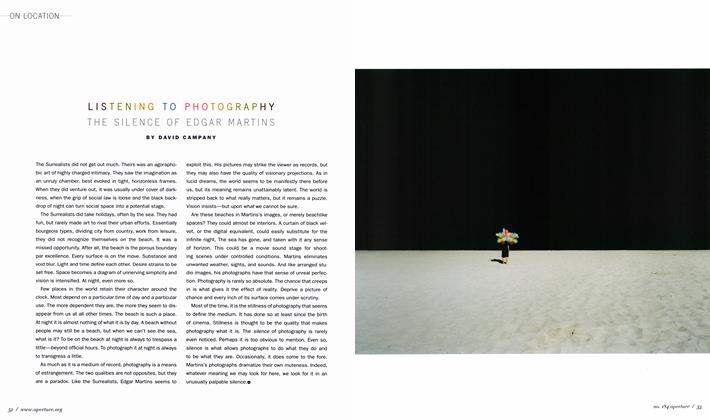

On LocationListening To Photography The Silence Of Edgar Martins

Fall 2006 By David Campany -

On Location

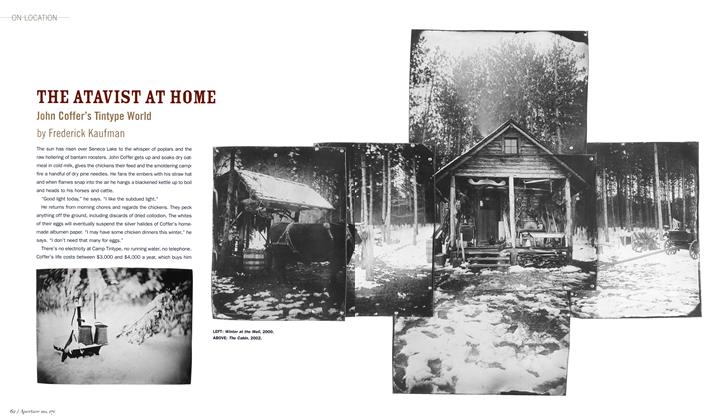

On LocationThe Atavist At Home: John Coffer's Tinytpe World

Spring 2003 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

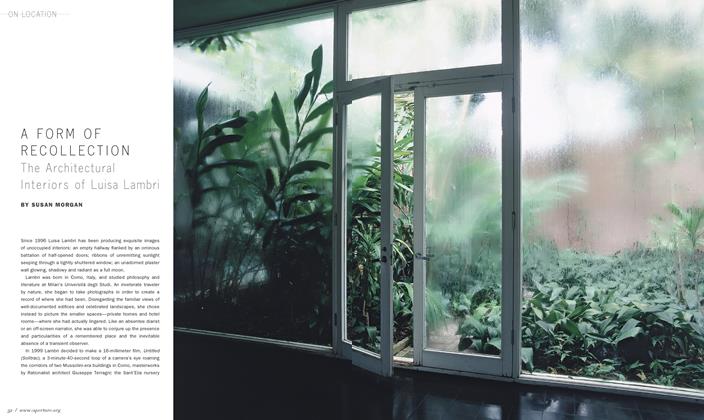

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan