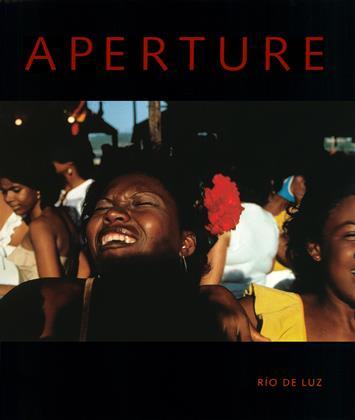

Río de Luz

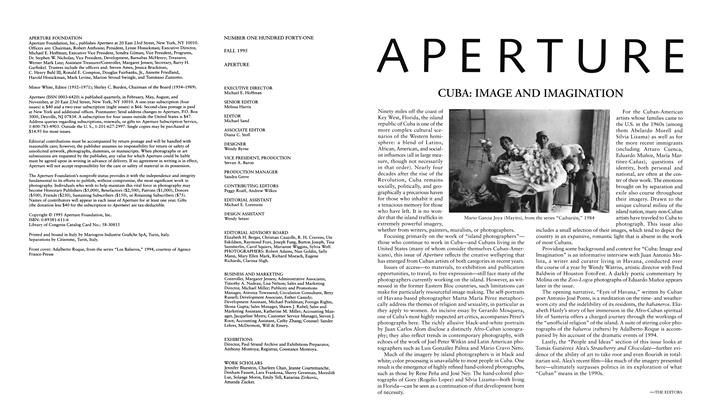

Editor's Note

Aperture has often focused on the work of individual photographers and countries but has rarely addressed the crosscultural sensibilities of a particular region. "Río de Luz," or River of light, attempts to do just that. The title serves not only as a metaphor for the publication as a whole, but also for the fluidity with which its artists and images cross borders of all kinds. By moving through various experiences and issues common to many Latin American countries, "Río de Luz" celebrates a broad and diverse culture and its artists both in terms of what binds them and what distinguishes them from one another.

A tribute to the Mexican book series Río de Luz, one of the most important collections of Latin American photography ever compiled, this issue of Aperture was guest edited by Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, one of the original editors of the series. It affords our readers the unprecedented opportunity to experience the essence of this seminal, often controversial, short-lived series of books. At the same time, it reconsiders both the work and the themes embodied in the original books, offering insightful readings that intensify our understanding of the work. We are grateful for the intelligent and creative collaboration of all the writers and photographers, and of course to our esteemed friend and colleague, Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, who below introduces the project.

THE EDITORS

Río de Luz began in 1984, and by 1989 twenty volumes had been published. The title, from a poem by Gilberto Owen, faithfully expresses the objectives which served as the driving force behind the project.

When Aperture proposed that we collaborate on an issue devoted to Río de Luz that, rather than be a "greatest hits" of the original series, would instead provide a new context for looking at the work ten to fifteen years later, I asked: how could we bring together the richness and complexity of the twenty volumes produced over the course of five years in this single issue—with the medley of topics covered and such magnificent photographic styles?

Our goal, then, was to incorporate as many images and photographers as possible, while revisiting the work from a contemporary perspective, and in light of changes in the cultural, political, and social climate of Latin America.

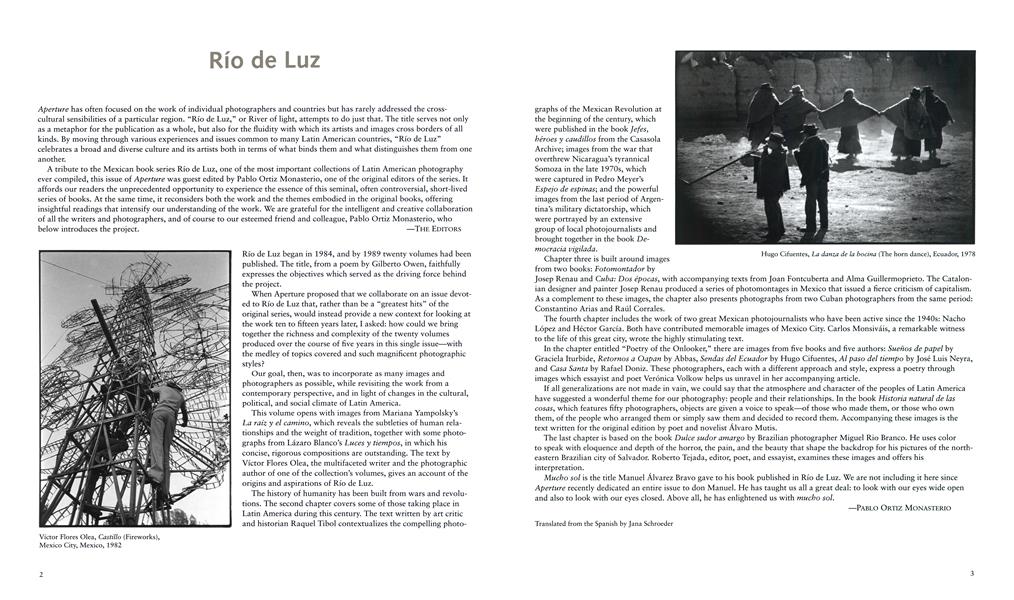

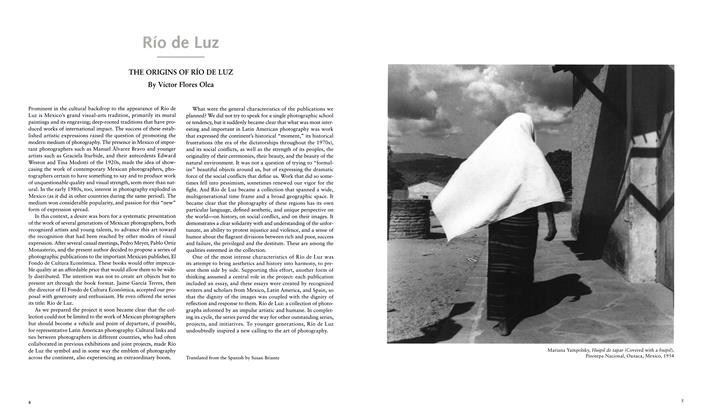

This volume opens with images from Mariana Yampolsky’s La raíz y el camino, which reveals the subtleties of human relationships and the weight of tradition, together with some photographs from Lázaro Blanco’s Luces y tiempos, in which his concise, rigorous compositions are outstanding. The text by Victor Flores Olea, the multifaceted writer and the photographic author of one of the collection’s volumes, gives an account of the origins and aspirations of Río de Luz.

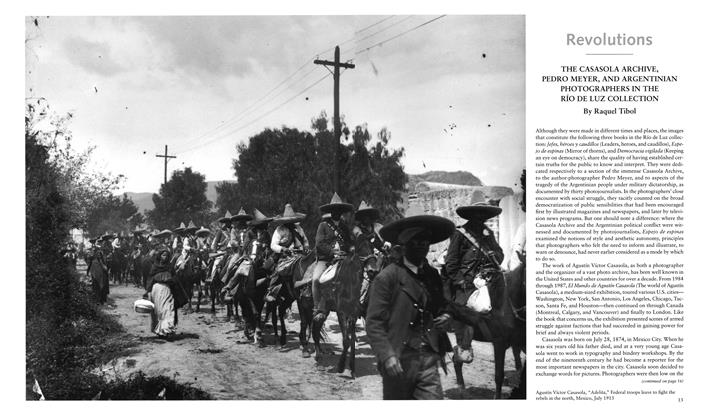

The history of humanity has been built from wars and revolutions. The second chapter covers some of those taking place in Latin America during this century. The text written by art critic and historian Raquel Tibol contextualizes the compelling photographs of the Mexican Revolution at the beginning of the century, which were published in the book Jefes, héroes y caudillos from the Casasola Archive; images from the war that overthrew Nicaragua’s tyrannical Somoza in the late 1970s, which were captured in Pedro Meyer’s Espejo de espinas; and the powerful images from the last period of Argentina’s military dictatorship, which were portrayed by an extensive group of local photojournalists and brought together in the book Democracia vigilada.

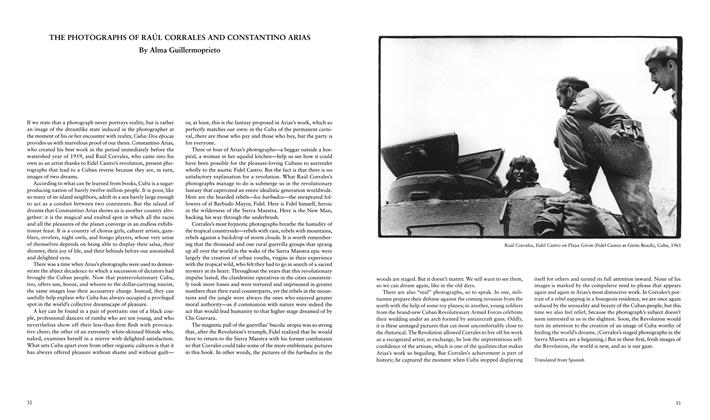

Chapter three is built around images from two books: Fotomontador by Josep Renau and Cuba: Dos épocas, with accompanying texts from Joan Fontcuberta and Alma Guillermoprieto. The Catalonian designer and painter Josep Renau produced a series of photomontages in Mexico that issued a fierce criticism of capitalism. As a complement to these images, the chapter also presents photographs from two Cuban photographers from the same period: Constantino Arias and Raúl Corrales.

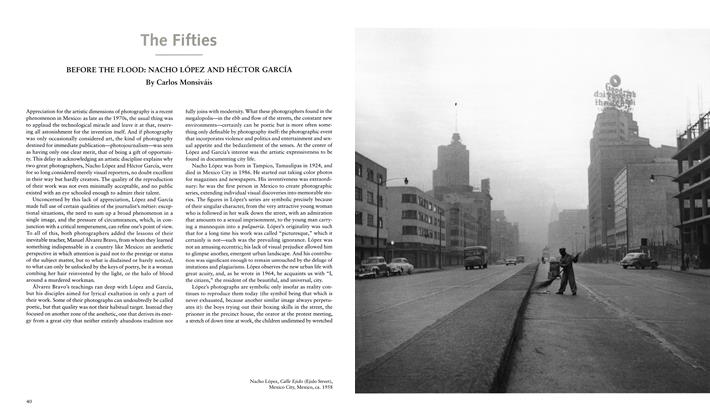

The fourth chapter includes the work of two great Mexican photo journalists who have been active since the 1940s: Nacho López and Héctor García. Both have contributed memorable images of Mexico City. Carlos Monsiváis, a remarkable witness to the life of this great city, wrote the highly stimulating text.

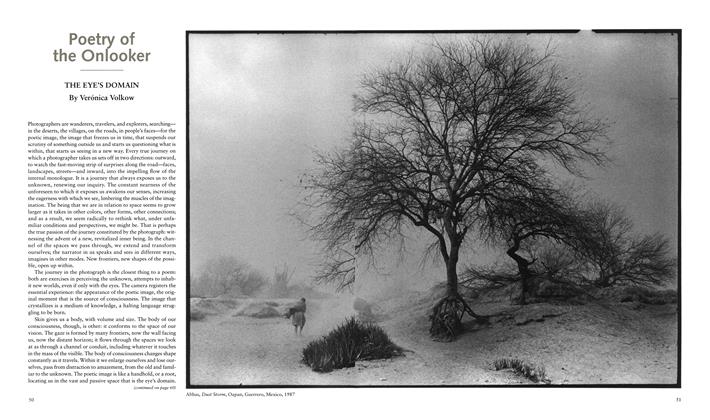

In the chapter entitled “Poetry of the Onlooker,” there are images from five books and five authors: Sueños de papel by Graciela Iturbide, Retornos a Oapan by Abbas, Sendas del Ecuador by Hugo Cifuentes, Al paso del tiempo by José Luis Neyra, and Casa Santa by Rafael Doniz. These photographers, each with a different approach and style, express a poetry through images which essayist and poet Verónica Volkow helps us unravel in her accompanying article.

If all generalizations are not made in vain, we could say that the atmosphere and character of the peoples of Latin America have suggested a wonderful theme for our photography: people and their relationships. In the book Historia natural de las cosas, which features fifty photographers, objects are given a voice to speak—of those who made them, or those who own them, of the people who arranged them or simply saw them and decided to record them. Accompanying these images is the text written for the original edition by poet and novelist Alvaro Mutis.

The last chapter is based on the book Dulce sudor amargo by Brazilian photographer Miguel Rio Branco. He uses color to speak with eloquence and depth of the horror, the pain, and the beauty that shape the backdrop for his pictures of the northeastern Brazilian city of Salvador. Roberto Tejada, editor, poet, and essayist, examines these images and offers his interpretation.

Mucho sol is the title Manuel Alvarez Bravo gave to his book published in Río de Luz. We are not including it here since Aperture recently dedicated an entire issue to don Manuel. He has taught us all a great deal: to look with our eyes wide open and also to look with our eyes closed. Above all, he has enlightened us with mucho sol.

PABLO ORTIZ MONASTERIO

Translated from the Spanish by Jana Schroeder

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Revolutions

RevolutionsThe Casasola Archive, Pedro Meyer, And Argentinian Photographers In The Río De Luz Collection

Fall 1998 By Raquel Tibol -

Poetry Of The Onlooker

Poetry Of The OnlookerThe Eye's Domain

Fall 1998 By Verónica Volkow -

The Fifties

The FiftiesBefore The Flood: Nacho López And Héctor García

Fall 1998 By Carlos Monsiváis -

Sweet Bitter Sweat

Sweet Bitter SweatMiguel Rio Branco

Fall 1998 By Roberto Tejada -

The American Way Of Life And Cuba

The American Way Of Life And CubaThe Photographs Of Raúl Corrales And Constantino Arias

Fall 1998 By Alma Guillermoprieto -

Río De Luz

Río De LuzThe Origins Of Río De Luz

Fall 1998 By Víctor Flores Olea