THE PENCIL OF NATURE

Photography, Industry, and the Book

The plates of the present work are impressed by the agency of Light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation. —W. H. F. Talbot, “Notice to the Reader,” The Pencil of Nature, 1844-46 A wonderful illustration of modern necromancy. —The Athenaeum, 1845

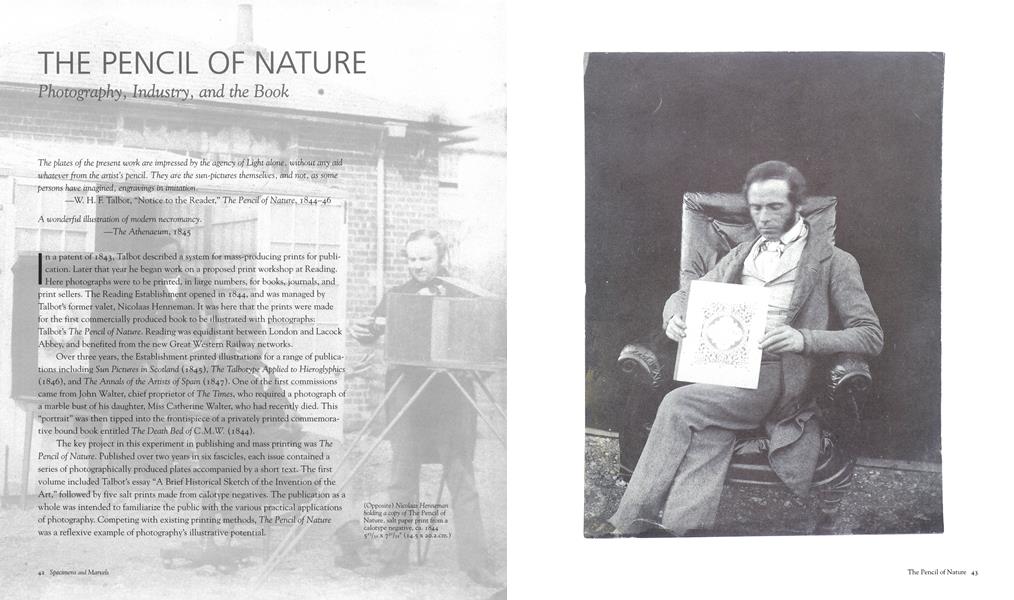

In a patent of 1843, Talbot described a system for mass-producing prints for publication. Later that year he began work on a proposed print workshop at Reading. Here photographs were to be printed, in large numbers, for books, journals, and print sellers. The Reading Establishment opened in 1844, and was managed by Talbot’s former valet, Nicolaas Henneman. It was here that the prints were made for the first commercially produced book to be illustrated with photographs: Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature. Reading was equidistant between London and Lacock Abbey, and benefited from the new Great Western Railway networks.

Over three years, the Establishment printed illustrations for a range of publications including Sun Pictures in Scotland (1845), The Talbotype Applied to Hieroglyphics (1846), and The Annals of the Artists of Spain (1847). One of the first commissions came from John Walter, chief proprietor of The Times, who required a photograph of a marble bust of his daughter, Miss Catherine Walter, who had recently died. This “portrait” was then tipped into the frontispiece of a privately printed commemorative bound book entitled The Death Bed ofC.M.W. (1844).

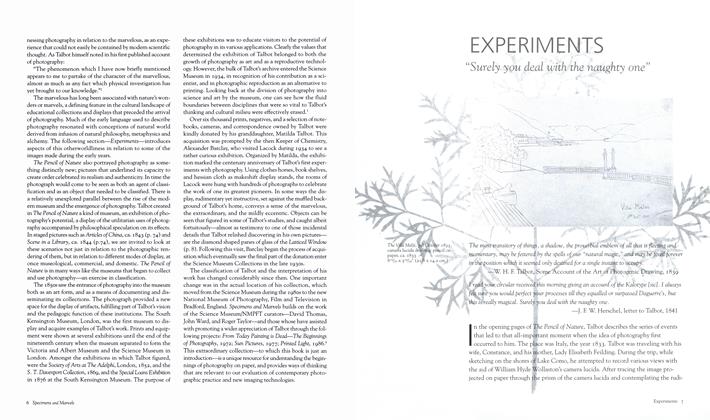

The key project in this experiment in publishing and mass printing was The Pencil of Nature. Published over two years in six fascicles, each issue contained a series of photographically produced plates accompanied by a short text. The first volume included Talbot’s essay “A Brief Historical Sketch of the Invention of the Art,” followed by five salt prints made from calotype negatives. The publication as a whole was intended to familiarize the public with the various practical applications of photography. Competing with existing printing methods, The Pencil of Nature was a reflexive example of photography’s illustrative potential.

During the publication of The Pencil of Nature, Talbot embarked on another photographically illustrated book that was quite distinct from his previous attempt to classify photography: Sun Pictures in Scotland (1845), which introduced readers to a Romantic potential in the medium, was dominated by pictures, contained little text, and sought to evoke the writings and the descriptions of the Scottish land' scape found in the work of Sir Walter Scott. In the early nineteenth century, travel' ers in search of the picturesque were visiting parts of Scotland associated with Scott, namely the Trossachs and Loch Katrine, the backdrop for his book The Lady of the Lake (1810). Scott combined folk traditions and rural history with detailed accounts of the Scottish landscape. Talbot’s pictures can be seen as participating in the growing tourist fascination with Scotland. The intellectual baggage that would have accompanied these upper-class travelers would have included the works of Wordsworth, Goethe, and Schiller.

Several books made at Reading have become historically important, including The Annals of the Artists of Spain (1848), the first use of photography in the study of art history. Yet these books were not financially successful. Since the printing was affected by inconsistencies in the photographic process, impurities in the water, and even by the weather (sunlight was essential for printmaking), quality was variable and production was slow. The Establishment closed in 1847 and the business moved to London.