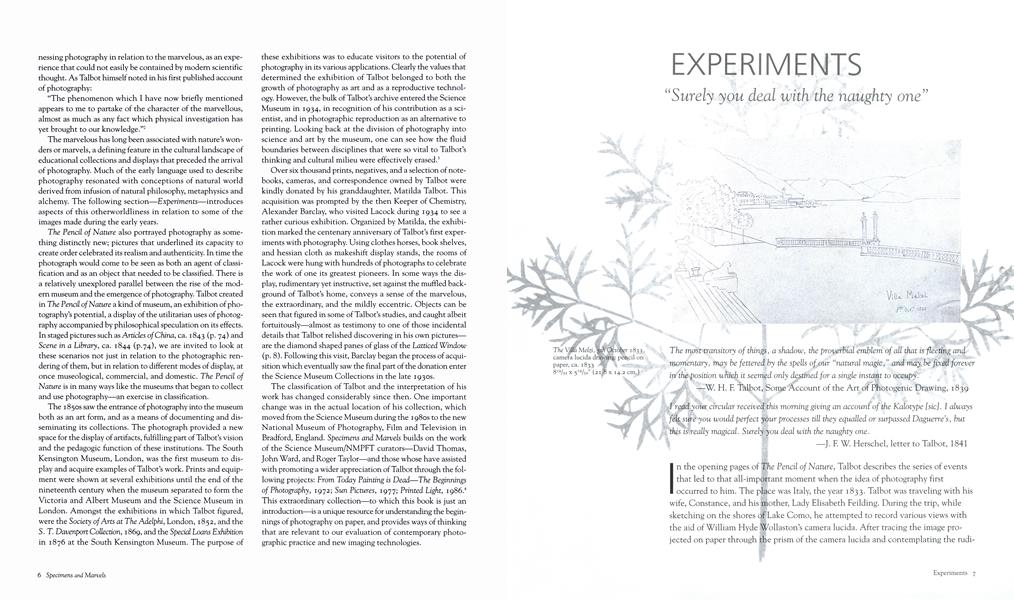

EXPERIMENTS

“Surely you deal with the naughty one”

The most transitory of things, a shadow, the proverbial emblem of all that is fleeting and momentary, may be fettered by the spells of our “natural magic,” and may be fixed forever in the position which it seemed only destined for a single instant to occupy. —W. H. F. Talbot, Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, 1839

I read your circular received this morning giving an account of the Kalotype [sic]. I always felt sure you would perfect your processes till they equalled or surpassed Daguerre’s, but this is really magical. Surely you deal with the naughty one. —J. F. W. Herschel, letter to Talbot, 1841

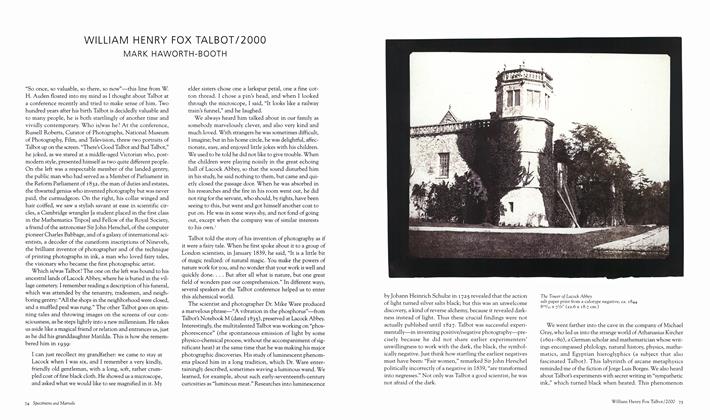

In the opening pages of The Pencil of Nature, Talbot describes the series of events that led to that all-important moment when the idea of photography first occurred to him. The place was Italy, the year 1833. Talbot was traveling with his wife, Constance, and his mother, Lady Elisabeth Feilding. During the trip, while sketching on the shores of Lake Como, he attempted to record various views with the aid of William Hyde Wollaston’s camera lucida. After tracing the image projected on paper through the prism of the camera lucida and contemplating the rudimentary sketches before him, Talbot confronted in the uncomplimentary network of pencil lines—“traces on the paper melancholy to behold.”’

Continuing his account (and still lamenting his inability to draw), Talbot considers in contrast, the images he had seen on the glass screen of the camera obscura the preferred drawing aid of eighteenth-century artists:

And this led me to reflect on the inimitable beauty of the pictures of nature’s painting which the glass lens of the Camera throws upon the paper in its focus—fairy pictures, creations of a moment and destined as rapidly to fade away.

It was during these thoughts that the idea occurred to me . . . how charming it would be if it were possible to cause these natural images to imprint themselves durably and remain fixed upon the paper! And why should it not be possible? I asked myself.6

The idea can be seen, then, to have arisen from both scientific conjecture and, as Talbot himself noted, “Whether it had ever occurred to me before amid floating philosophic visions, I know not. . . Arguably, the idea was possibly driven by a sense of failure as a draughtsman, and perhaps of wounded pride or humility arising from that failure in the presence of Talbot’s wife and mother. Ineptitude may have been a rare experience for him, accomplished as he was in botany, mathematics, chemistry, etymology, philology, physics, and optics. Making a note of his idea, he returned to England in 1834 and began his experiments “on the art of fixing a shadow.”8

The causes and effects behind photography had been discussed in principle by a number of earlier European thinkers. In 1669, for example, Athanasius Kircher had published a book containing an illustration of the use of the sun for printing, and in 1725 Johann Heinrich Schulze had observed the light-sensitive properties of silver salts. To these observations must be added the practical experiments of Thomas Wedgwood and Humphry Davy in the 1790s. Talbot referred to the latter partnership in The Pencil of Nature, stating that he was unaware of these experiments before undertaking his own researches. However, there are similarities between his project and theirs in that Wedgwood and Davy apparently reproduced outlines or shadows of objects (including leaves, insect wings, and paintings on glass) on a surface sensitized with silver nitrate. They also proposed the use of a camera obscura.9

Phrases such as “fairy pictures,” “natural magic,” “words of light,” the “black art,” “magic pictures,” and “nature’s marvels” were among the early vocabulary used to describe photography.10 The nineteenth century was a period of great advances in both the arts and the sciences, but Talbot’s thinking was also infused with a blend of natural philosophy, Romanticism, and experimental science linked with the latter half of the eighteenth century. The language he used to describe photography resonates with the irrational or supernatural. Despite the emergence of modern scientific thinking, alchemy remained a powerful symbol of chemical change during this period, even if it was part of an outdated and occult view of the world. The miraculous transformation of substances sought in alchemy evoked ideas of photography as a piece of “natural magic.”11 This idea was to gain strength with Talbot’s discovery of the latent image in September 1840—the process by which after a brief exposure a negative image could be chemically developed out of the sensitized paper—an innovation that led Talbot’s friend Sir John Herschel to the diabolical suggestion, “Surely you deal with the naughty one.” This playful notion of a satanic partnership in the discovery of the negative/positive process reflects Herschel’s awareness of how significant this discovery was. The concept of latency had figured in a notebook of Talbot’s as early as around 1831, where, using chemical combinations to produce “secret writing,” he wrote, “First concealed, at last I appear.”

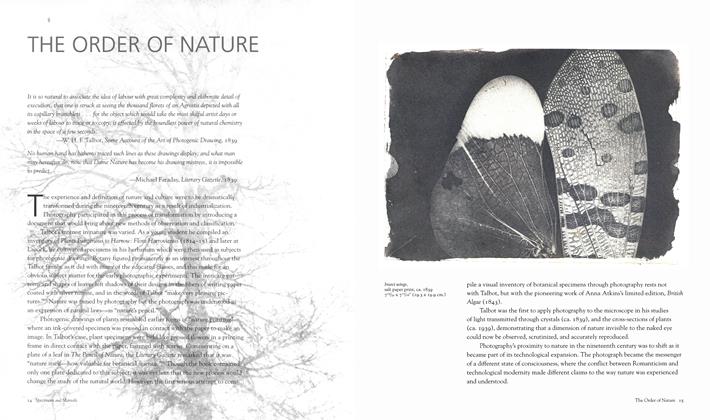

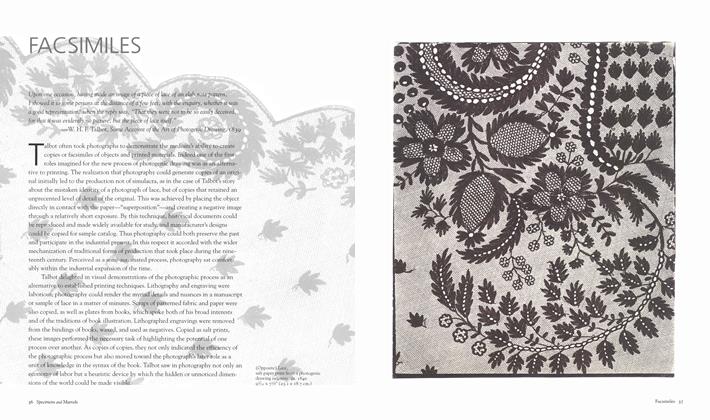

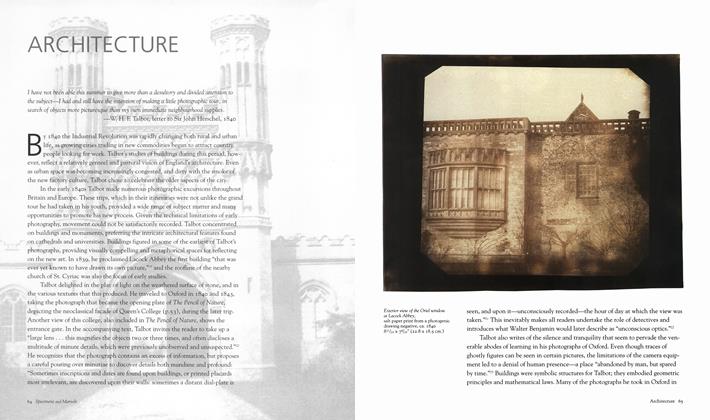

Talbot’s surviving images from this initial period of experimentation were produced in three different ways: contact prints of objects, images made using a modified camera obscura (made by a local carpenter and affectionately termed “mousetraps” by Talbot’s wife on account of their size and appearance), and the solar microscope. Each method involved a different relationship between the object and the way it is represented and were collectively described as photogenic drawings. Photographs of lace, Lacock Abbey, painted glass, and botanical specimens also supposed a new kind of observer, one who can contain the world and its objects in either miniaturized or enlarged form.

Talbot’s work was promoted via the Royal Society, where his experiments and discoveries were described in a paper read to its members on January 31, 1839. This lecture took place over three weeks after the announcement in Paris of another photographic process invented by Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre. Seeking to claim his position in the origins of photography, Talbot reinforced his written account with a series of small “exhibitions,” the first being first in the library of the Royal Institution. In August that year he showed a selection of “specimens” at a Birmingham meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Categories included “Images obtained by the direct action of light and of the same size with the objects (lace, lithographs, botanical specimens);” reversed images, requiring the action of light to be twice employed (copies of painted glass, and printed pages from books); views taken with the Camera Obscura (Lacock Abbey); “Images made with the Solar Microscope (lace magnified 100 and 400 times).” These images were part of an early complex of images that provided a set of characteristics from which to gauge the potential of photography.

In a letter to Talbot in 1840, his uncle William Fox-Strangways classed photogenic drawings into ten divisions and proposed that “Two or three styles might be brought into one drawing and if well combined would make a better specimen of the art.”12 Talbot’s pictures are predominantly hybrid in construction: not only do they concentrate on the reproductive potential of photography, they engage with the subjects of his interests and philosophical investigations on many levels. It is with this in mind that the following sections of this book have been put together.