PEOPLE, PLACES, AND THINGS

I long to have such a memorial of every being dear to me in the world. It is not merely the likeness which is precious in such cases—but the association and the sense of nearness involved in the thing ... the fact of the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever! —Elizabeth Barrett, extract from a letter to Mary Russell Mitford, 1843

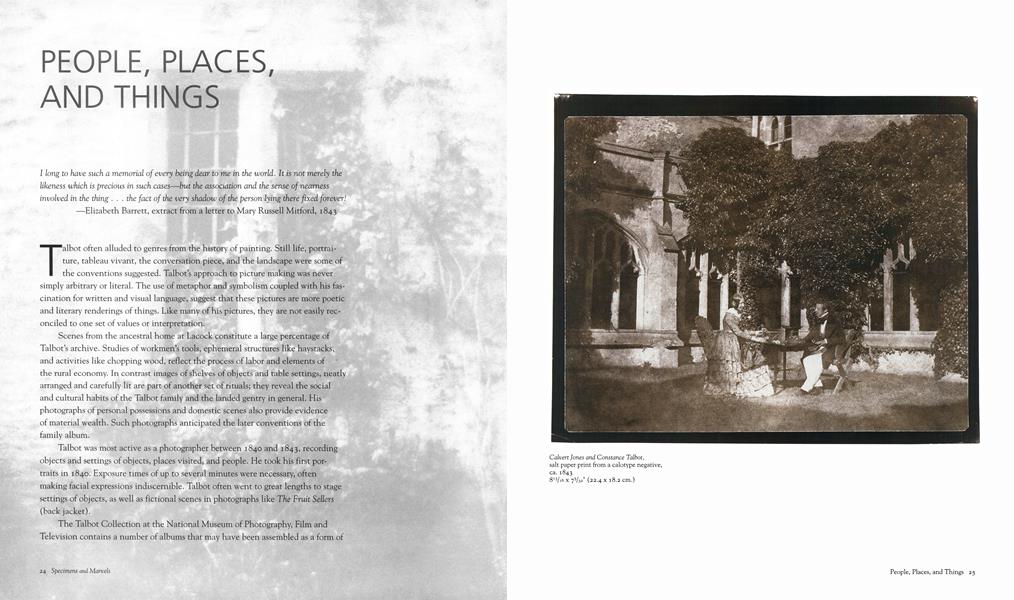

Talbot often alluded to genres from the history of painting. Still life, portraiture, tableau vivant, the conversation piece, and the landscape were some of the conventions suggested. Talbot's approach to picture making was never simply arbitrary or literal. The use of metaphor and symbolism coupled with his fascination for written and visual language, suggest that these pictures are more poetic and literary renderings of things. Like many of his pictures, they are not easily reconciled to one set of values or interpretation.

Scenes from the ancestral home at Lacock constitute a large percentage of Talbot’s archive. Studies of workmen’s tools, ephemeral structures like haystacks, and activities like chopping wood, reflect the process of labor and elements of the rural economy. In contrast images of shelves of objects and table settings, neatly arranged and carefully lit are part of another set of rituals; they reveal the social and cultural habits of the Talbot family and the landed gentry in general. His photographs of personal possessions and domestic scenes also provide evidence of material wealth. Such photographs anticipated the later conventions of the family album.

Talbot was most active as a photographer between 1840 and 1843, recording objects and settings of objects, places visited, and people. He took his first portraits in 1840. Exposure times of up to several minutes were necessary, often making facial expressions indiscernible. Talbot often went to great lengths to stage settings of objects, as well as fictional scenes in photographs like The Fruit Sellers (back jacket).

The Talbot Collection at the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television contains a number of albums that may have been assembled as a form of “trade catalogue” to demonstrate the potential of photography to those interested in licensing the process. They can also be seen as part of the nineteenth-century fashion for compiling albums as a form of diary. These albums are like portable museums, each offering a kind of microcosm of the world as image. Susan Stewart, in her book On Longing (1993) explores the importance of narrative as part of the process of acquisition and display of souvenirs: “The photograph as souvenir is a logical extension of the pressed flower, the preservation of an instant in time through a reduction of physical dimensions and a corresponding increase in the significance supplied by means of narrative.”24 For Talbot, the studies of family members and the contents of his home at Lacock, are essential for understanding the narrative of photographic experimentation, but also an intimate distance from which to explore social history through photography.