FACSIMILES

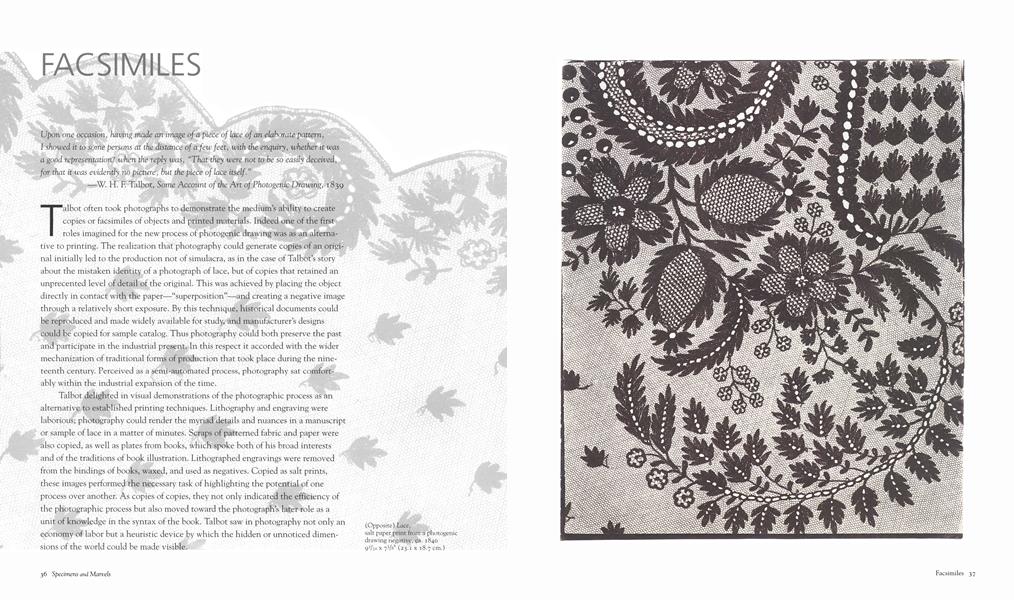

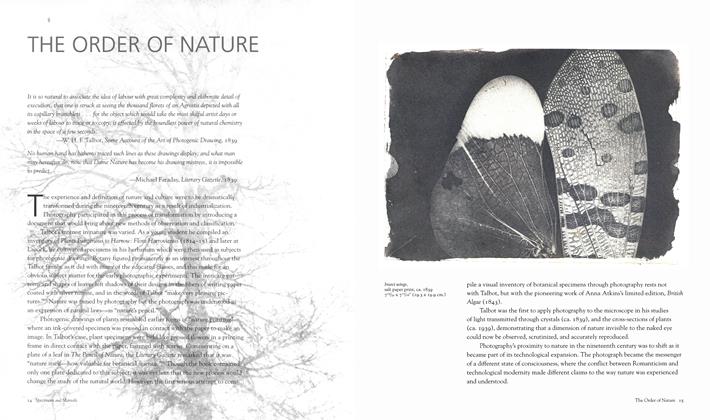

Upon one occasion, having made an image of a piece of lace of an elaborate pattern, I showed it to some persons at the distance of a few feet, with the enquiry, whether it was a good representation? when the reply was, “That they were not to be so easily deceived, for that it was evidently no picture, but the piece of lace itself.” —W. H. F. Talbot, Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, 1839

Talbot often took photographs to demonstrate the medium's ability to create copies or facsimiles of objects and printed materials. Indeed one of the first roles imagined for the new process of photogenic drawing was as an alternative to printing. The realization that photography could generate copies of an original initially led to the production not of simulacra, as in the case of Talbot’s story about the mistaken identity of a photograph of lace, but of copies that retained an unprecented level of detail of the original. This was achieved by placing the object directly in contact with the paper—“superposition”—and creating a negative image through a relatively short exposure. By this technique, historical documents could be reproduced and made widely available for study, and manufacturer’s designs could be copied for sample catalog. Thus photography could both preserve the past and participate in the industrial present. In this respect it accorded with the wider mechanization of traditional forms of production that took place during the nineteenth century. Perceived as a semi-automated process, photography sat comfortably within the industrial expansion of the time.

Talbot delighted in visual demonstrations of the photographic process as an alternative to established printing techniques. Lithography and engraving were laborious; photography could render the myriad details and nuances in a manuscript or sample of lace in a matter of minutes. Scraps of patterned fabric and paper were also copied, as well as plates from books, which spoke both of his broad interests and of the traditions of book illustration. Lithographed engravings were removed from the bindings of books, waxed, and used as negatives. Copied as salt prints, these images performed the necessary task of highlighting the potential of one process over another. As copies of copies, they not only indicated the efficiency of the photographic process but also moved toward the photograph’s later role as a unit of knowledge in the syntax of the book. Talbot saw in photography not only an economy of labor but a heuristic device by which the hidden or unnoticed dimensions of the world could be made visible.

By copying words and images, Talbot considered the photograph in relation to existing methods of reproduction, such as handwriting, lithography, engraving, and letterpress printing. He carefully orchestrated these uses, comparing marks made by hand with marks made by machine, and offering reflexive statements on the inherent value of his photographic process in relation to both. His reproduction of texts in images such as Imitation of Printing, ca. 1844 (p. 40), and a published version of his essay Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing underline photographic reproduction in the text represented. A poem by Thomas Moore shows a more subtle comparison between media: the original hand-written version has been photographed and the words “Common Ink” have been written—in ink—on the surface of the print (p. 74). Here is an obvious yet compelling engagement with the facsimile dimension of photography.

It is well known that Talbot felt disgruntled by Daguerre’s status in relation to the origins of photography. By copying daguerreotypes, he made a simple yet poignant claim for photography on paper, and for the calotype process. A handwritten label used as a negative, bearing the words “Specimen of Talbotype (or Calotype) Photogenic Drawing (p. 40),” performed a similar task of underlining what was unique about Talbot’s negative/positive process.

Photography entered the visual economy of the nineteenth century providing a new level of realism that redefined the role of the artist, and brought with it increased production. Subsequently ideas of the original and the copy were to change.