THE ORDER OF NATURE

It is so natural to associate the idea of labour with great complexity and elaborate detail of execution, that one is struck at seeing the thousand florets of an Agrostis depicted with all its capillary branchlets . . . for the object which would take the most skilful artist days or weeks of labour to trace or to copy, is effected by the boundless power of natural chemistry in the space of a few seconds.

—W. H. F. Talbot, Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, 1839

No human hand has hitherto traced such lines as these drawings display; and what man may hereafter do, now that Dame Nature has become his drawing mistress, it is impossible to predict.

—Michael Faraday, Literary Gazette,’ 1839

The experience and definition of nature and culture were to be dramatically transformed during the nineteenth century as a result of industrialization. Photography participated in this process of transformation by introducing a document that would bring about new methods of observation and classification.

Talbot’s interest in nature was varied. As a young student he compiled an inventory of Plants Indigenous to Harrow: Flora Harroviensis (1814-15) and later at Lacock, he cultivated specimens in his herbarium which were then used as subjects for photogenic drawings^Botany figured prominently as an interest throughout the Talbot family, as it did with many of the educated classes, and this made for an obvious subject matter for the early photographic experiments. The intricate patterns and shapes of leaves left shadows of their designs in the fibers of writing paper coated with silver nitrate, and in the words of Talbot “make very pleasing pictures.”16 Nature was tamed by photography but the photograph was understood as an expression of natural laws—as “nature’s pencil.”1! « Bn ,

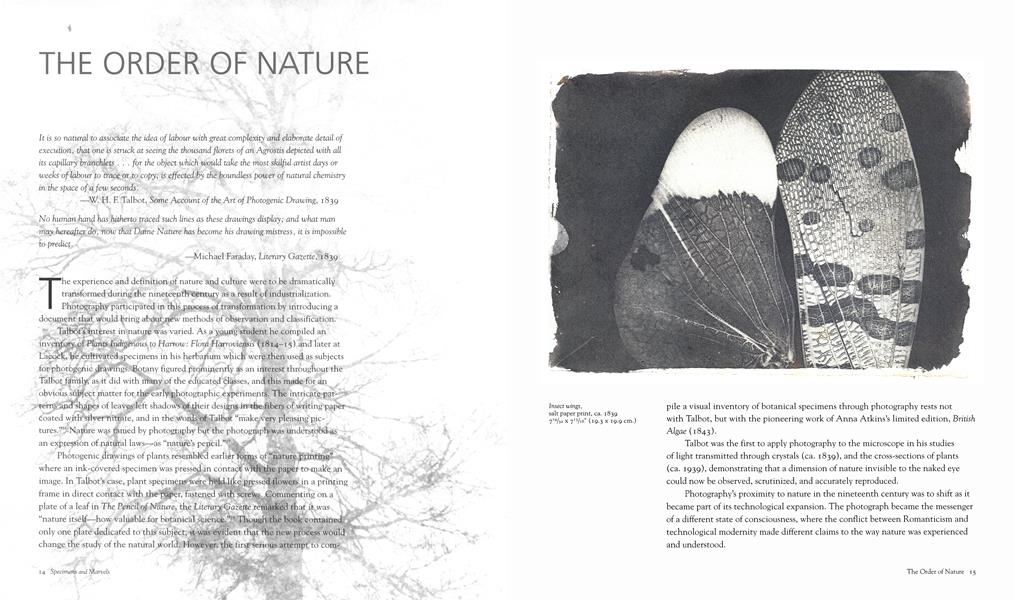

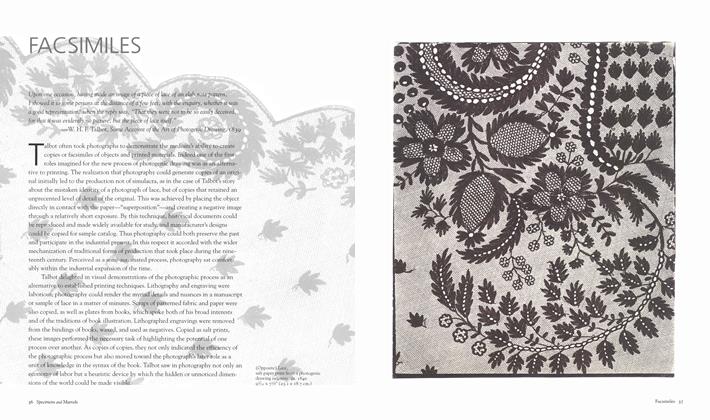

Photogenic drawings of plants resembled earlier forms of “nature printing” where an ink^covered specimen was pressed in contact with the paper to make an image. In Talbot’s case, plant specimens were held like pressed flowers in a printing frame in direct contact with the paper, fastened with screws. Commenting on a plate of a leaf in The Pencil of Nature, the Literary Gazette remarked that it was “nature itself—how valuable for botanical science.”18 Though the book contained only one plate dedicated to this subject, it was evident that the new process would change the study of the natural world. However, the first serious attempt to compile a visual inventory of botanical specimens through photography rests not with Talbot, but with the pioneering work of Anna Atkins’s limited edition, British Algae (1843).

Talbot was the first to apply photography to the microscope in his studies of light transmitted through crystals (ca. 1839), and the cross-sections of plants (ca. 1939), demonstrating that a dimension of nature invisible to the naked eye could now be observed, scrutinized, and accurately reproduced.

Photography’s proximity to nature in the nineteenth century was to shift as it became part of its technological expansion. The photograph became the messenger of a different state of consciousness, where the conflict between Romanticism and technological modernity made different claims to the way nature was experienced and understood.