In ancient Indigenous mythologies, the coyote is a sacred trickster that shifts between being a predator and a protector, its fanged mouth poised between a threatening snarl and a playful grin. For the Aztecs, the coyote was a god that frolicked among humans, sometimes provoking mayhem and disarray, and sometimes providing protection against greater evils. For the artist Guadalupe Maravilla, the coyote has been an intimate companion, and a protagonist in many of his elaborate sculptures, drawings, and highly choreographed performances based on autobiographical and fictional narratives. "Our ancestors were about creating mythologies, and I connected with that,” he says.

Maravilla anthropomorphizes the coyote into a canine-headed, larger-than-life being—somewhere between villain and superhero—that traverses great distances and crosses borders from El Salvador to New York. Maravilla operates on a vast mythological scale to cover his epic migratory journey as a child through Central America and Mexico and into the U.S. as part of the first wave of undocumented, unaccompanied youth arriving from that area. To be more specific, for his entire journey, Maravilla was accompanied by a series of "coyotes,” immigrant traffickers who safely relayed him to his destination. Displaced in his youth by El Salvador’s brutal civil war that spanned from 1979 through 1992, Maravilla and, eventually, his artistic practice and career were indelibly shaped by the events of history.

It makes sense that Maravilla would adopt a name and identity for himself that is also larger than life. Born Irvin Morazan, he changed his name to Guadalupe Maravilla in 2016, using the feminine first name his mother had intended to give him at birth since he was born on an auspicious date, December 12, when Latin America’s holiest patroness, the Virgin of Guadalupe, is celebrated. Taking his undocumented father’s fake last name, Maravilla, roughly translating to marvel or miracle, the artist emerged with a new identity and an origin story worthy of its telling.

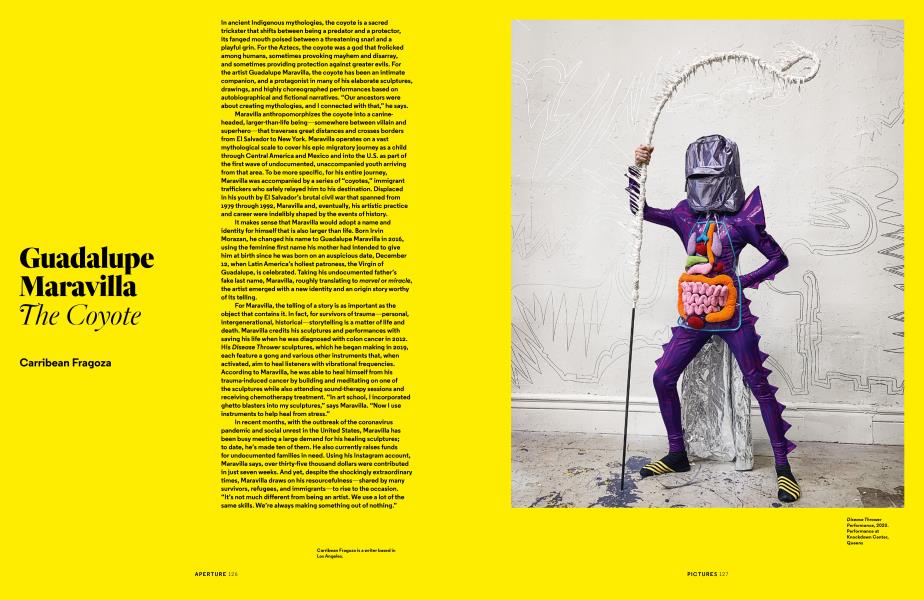

For Maravilla, the telling of a story is as important as the object that contains it. In fact, for survivors of trauma—personal, intergenerational, historical—storytelling is a matter of life and death. Maravilla credits his sculptures and performances with saving his life when he was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2012. His Disease Thrower sculptures, which he began making in 2019, each feature a gong and various other instruments that, when activated, aim to heal listeners with vibrational frequencies. According to Maravilla, he was able to heal himself from his trauma-induced cancer by building and meditating on one of the sculptures while also attending sound-therapy sessions and receiving chemotherapy treatment. "In art school, I incorporated ghetto blasters into my sculptures,” says Maravilla. "Now I use instruments to help heal from stress.”

In recent months, with the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and social unrest in the United States, Maravilla has been busy meeting a large demand for his healing sculptures; to date, he’s made ten of them. He also currently raises funds for undocumented families in need. Using his Instagram account, Maravilla says, over thirty-five thousand dollars were contributed in just seven weeks. And yet, despite the shockingly extraordinary times, Maravilla draws on his resourcefulness—shared by many survivors, refugees, and immigrants—to rise to the occasion. "It’s not much different from being an artist. We use a lot of the same skills. We’re always making something out of nothing.”

Carribean Fragoza is a writer based in Los Angeles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

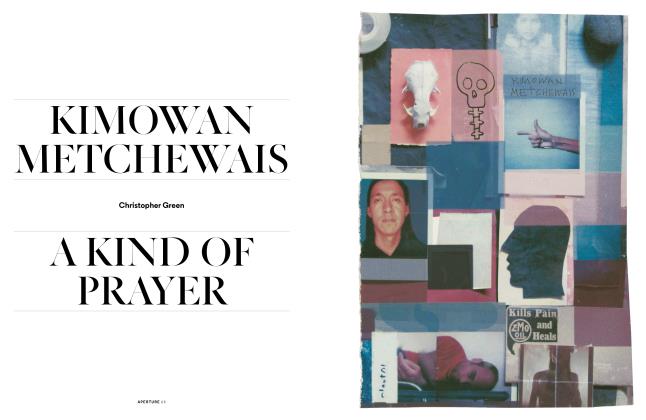

WordsKimowan Metchewais: A Kind Of Prayer

Fall 2020 By Christopher Green -

Words

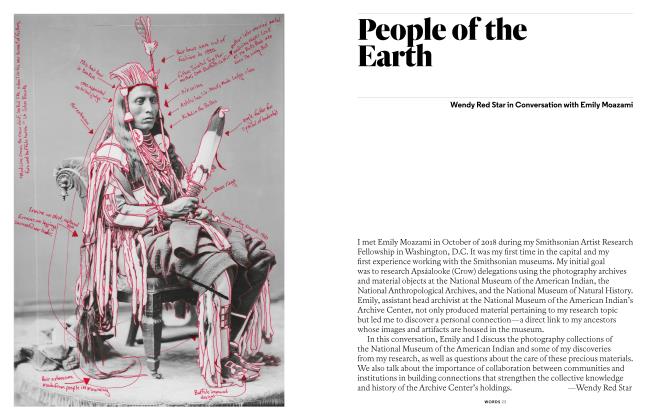

WordsPeople Of The Earth

Fall 2020 By Wendy Red Star -

Words

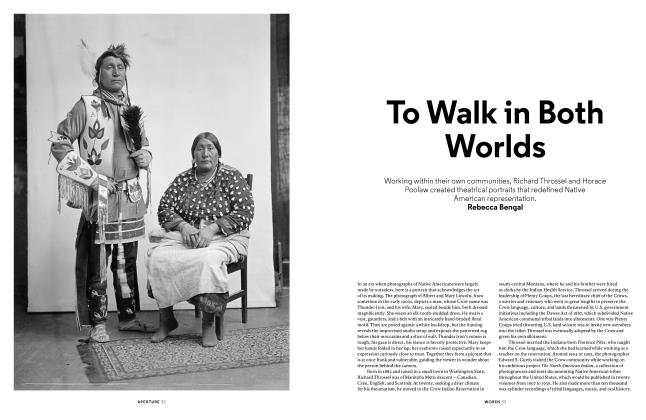

WordsTo Walk In Both Worlds

Fall 2020 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

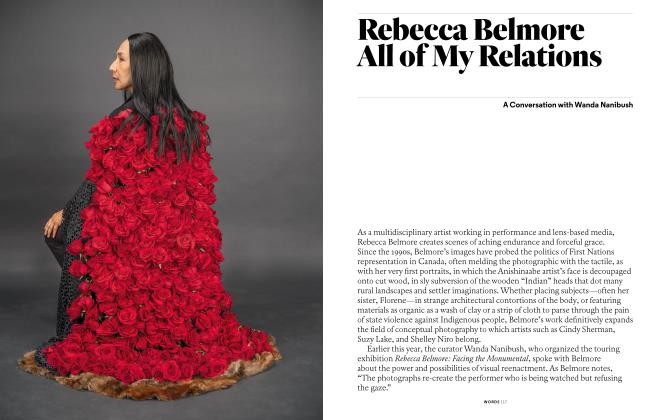

WordsRebecca Belmore: All Of My Relations

Fall 2020 By Wanda Nanibush -

Pictures

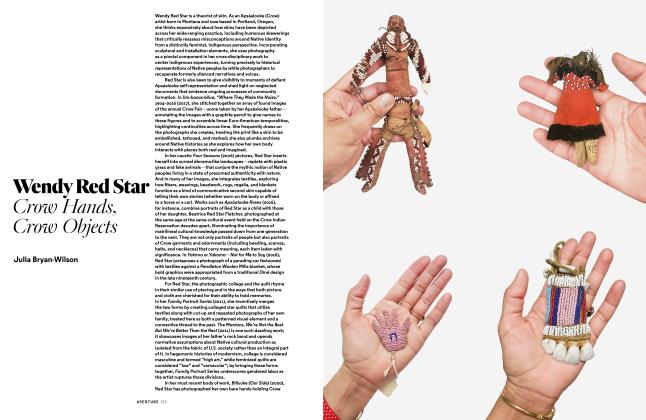

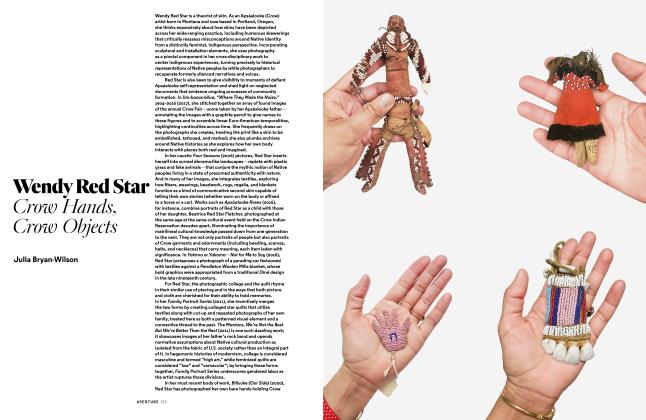

PicturesWendy Red Star

Fall 2020 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Pictures

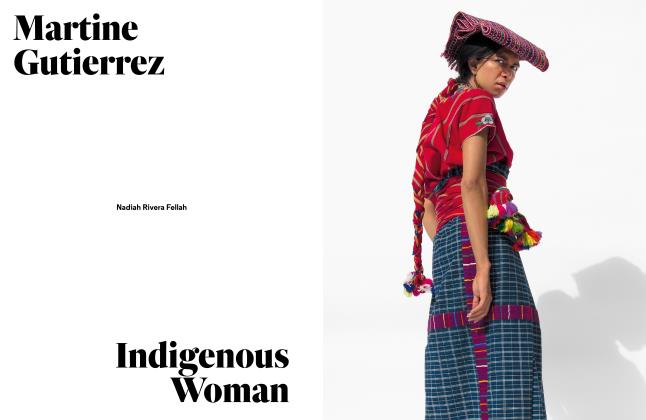

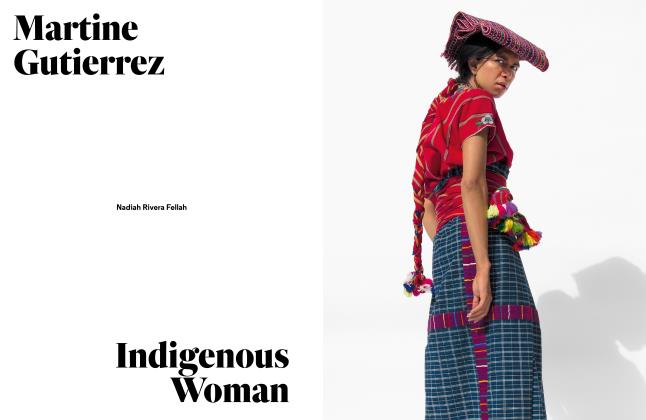

PicturesMartine Gutierrez: Indigenous Woman

Fall 2020 By Nadiah Rivera Fellah

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

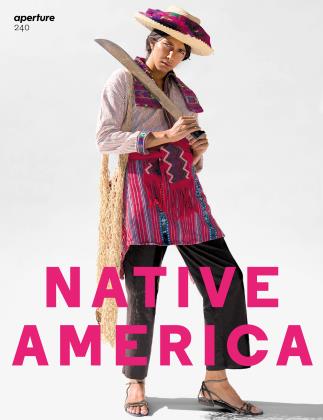

Native America

-

Pictures

PicturesDuane Linklater

Fall 2020 By Eungie Joo -

Pictures

PicturesWendy Red Star

Fall 2020 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Words

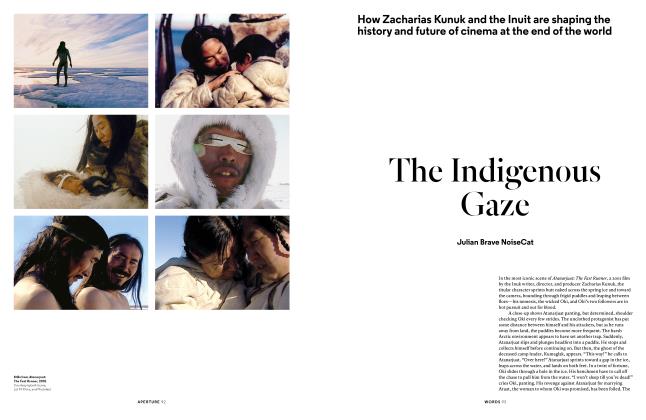

WordsThe Indigenous Gaze

Fall 2020 By Julian Brave Noisecat -

Pictures

PicturesMartine Gutierrez: Indigenous Woman

Fall 2020 By Nadiah Rivera Fellah -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteStrong Hearts: Native American Visions And Voices

Summer 1995 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

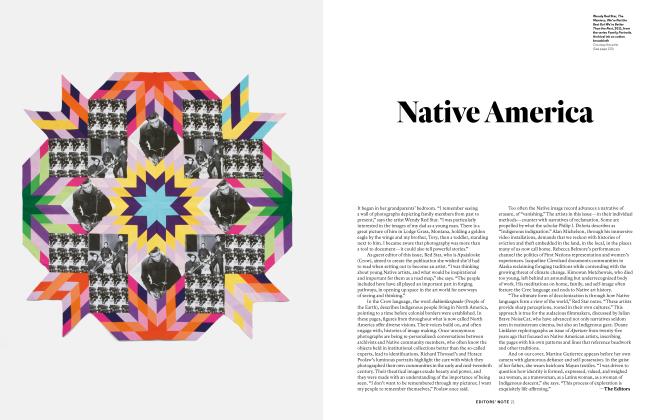

Editor's NoteNative America

Fall 2020 By The Editors