Rosângela Rennó

Thyago Nogueira

It might sound inaccurate to say that Rosângela Rennó's work is overlooked, as she is certainly celebrated in Brazil. But a quick look at the English and French photography compendiums on my shelves reveals no trace of her name, a fate she shares with many important photographers and artists from Latin America. One advantage of considering Rennó’s work in the context of this issue is that it helps us to understand just how the idea of being overlooked is a matter of point of view.

For most of photography’s history, talent has been thought to be revealed by the click of the shutter. This is not the case for Rennó. With an education in both art and architecture, she is a photographer who rarely picks up a camera. "When I’m among artists, I say I’m a photographer. When I’m among photographers, I say I’m an artist,” she claims provocatively. A tireless researcher and compulsive collector, Rennó finds her raw material in images culled from newspapers and archives, photos taken by unknown photographers and friends, and photographic paraphernalia snatched up at flea markets. Like words in a sentence, the artist reorganizes images and objects to invest them with new meaning. She does so to expose the often invisible codes of visual representation and the complex mechanisms that determine how photographs are produced and consumed.

Rennó's appropriation projects often address fraught moments in Brazilian history and politics. In Immemorial (1994), reproductions of damaged identificationcard photos of workers who died during the construction of Brasilia remind us of the outcomes of that utopian political project; in Red Series, Military Men (2000-2003), the red color that characterizes darkroom light is associated with violence and blood when suffusing found pictures of uniformed men. "Brazil is young, and it’s still learning to deal with its own memory,” says Rennó, who spent her formative years living under the country’s brutal dictatorship, which ended in 1985. Perhaps that experience sharpened the political and inquisitive tone of her work, and fostered her interest in discussing the relations between photography and public institutions, between a country’s archives and its broader historical and artistic heritage.

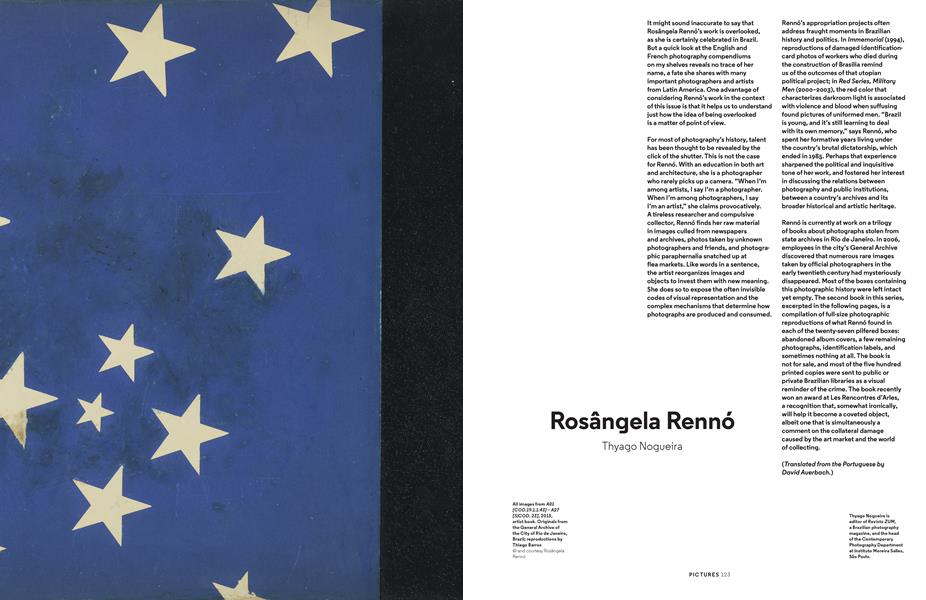

Rennó is currently at work on a trilogy of books about photographs stolen from state archives in Rio de Janeiro. In 2006, employees in the city’s General Archive discovered that numerous rare images taken by official photographers in the early twentieth century had mysteriously disappeared. Most of the boxes containing this photographic history were left intact yet empty. The second book in this series, excerpted in the following pages, is a compilation of full-size photographic reproductions of what Rennó found in each of the twenty-seven pilfered boxes: abandoned album covers, a few remaining photographs, identification labels, and sometimes nothing at all. The book is not for sale, and most of the five hundred printed copies were sent to public or private Brazilian libraries as a visual reminder of the crime. The book recently won an award at Les Rencontres d’Arles, a recognition that, somewhat ironically, will help it become a coveted object, albeit one that is simultaneously a comment on the collateral damage caused by the art market and the world of collecting.

(Translated from the Portuguese by David Auerbach.)

Thyago Nogueira is editor of Revista ZUM, a Brazilian photography magazine, and the head of the Contemporary Photography Department at Instituto Moreira Salles, Säo Paulo.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesPaul Trevor

Winter 2013 By Chris Boot -

Pictures

PicturesMarianne Wex

Winter 2013 By David Campany -

Pictures

PicturesKen Pate Roquette Rockers

Winter 2013 By Carole Naggar -

Pictures

PicturesMaria Sewcz Inter Esse

Winter 2013 By Britt Salvesen -

Pictures

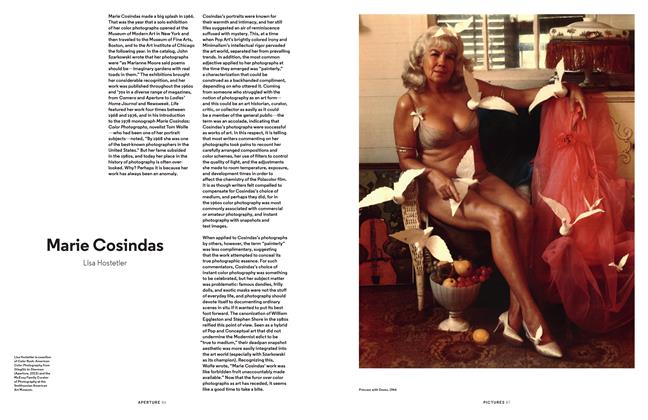

PicturesMarie Cosindas

Winter 2013 By Lisa Hostetler -

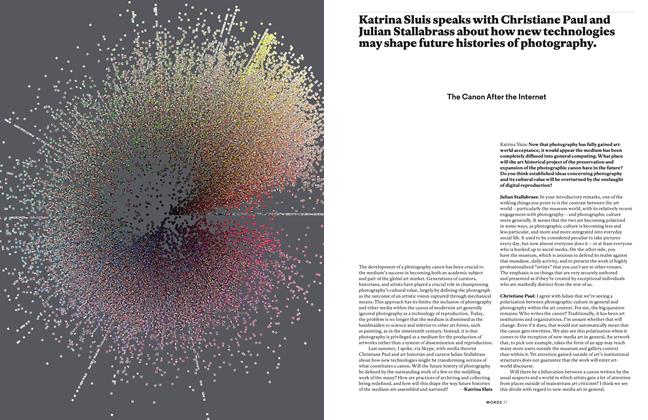

Words

WordsThe Canon After The Internet

Winter 2013 By Katrina Sluis

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Thyago Nogueira

Pictures

-

Pictures

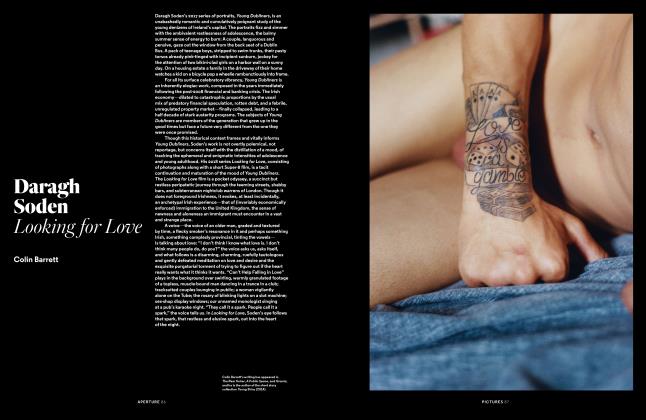

PicturesDaragh Soden

Summer 2020 By Colin Barrett -

Pictures

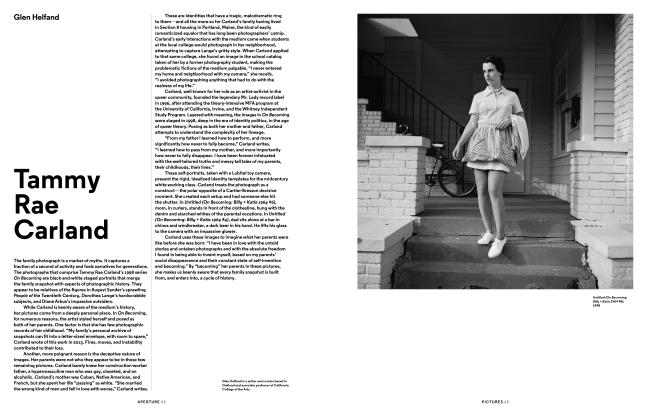

PicturesTammy Rae Carland

Winter 2018 By Glen Helfand -

Pictures

PicturesMichael Schmelling Your Blues

Fall 2016 By Kelefa Sanneh -

Pictures

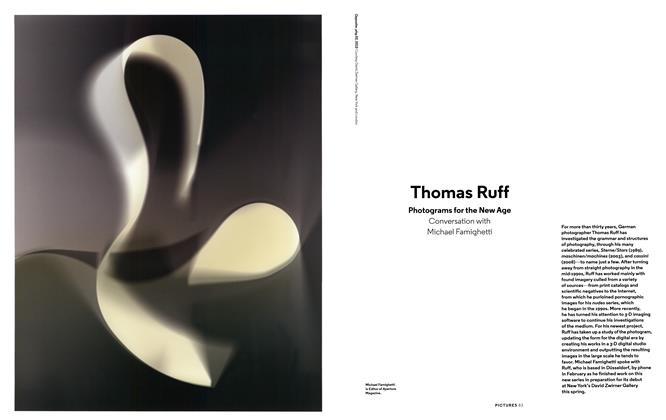

PicturesThomas Ruff: Photograms For The New Age

Summer 2013 By Michael Famighetti -

Pictures

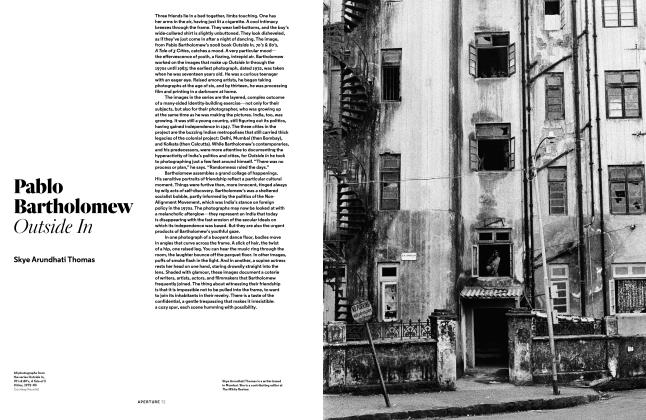

PicturesPablo Bartholomew

Summer 2020 By Skye Arundhati Thomas