Sounds

EDITORS’ NOTE

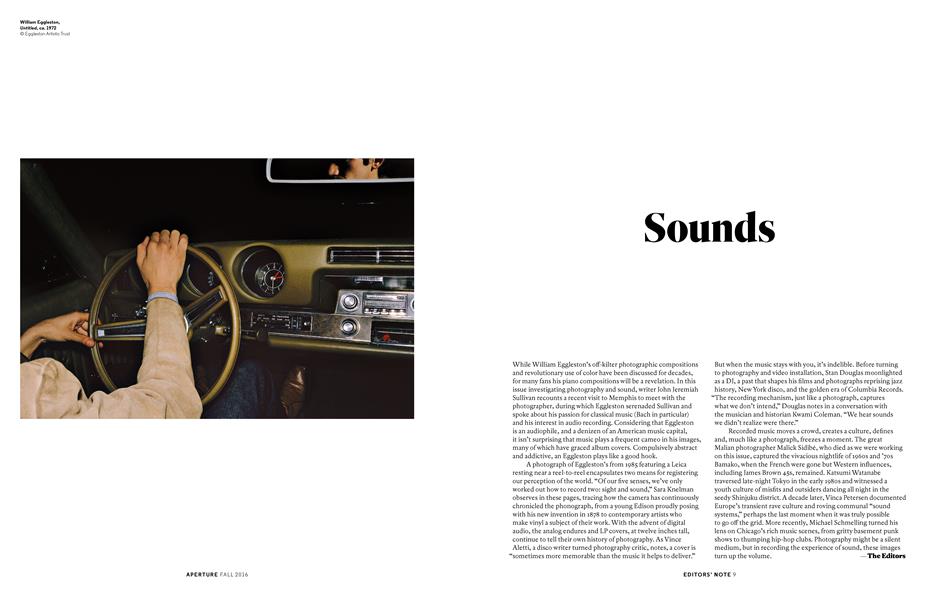

While William Eggleston’s off-kilter photographic compositions and revolutionary use of color have been discussed for decades, for many fans his piano compositions will be a revelation. In this issue investigating photography and sound, writer John Jeremiah Sullivan recounts a recent visit to Memphis to meet with the photographer, during which Eggleston serenaded Sullivan and spoke about his passion for classical music (Bach in particular) and his interest in audio recording. Considering that Eggleston is an audiophile, and a denizen of an American music capital, it isn’t surprising that music plays a frequent cameo in his images, many of which have graced album covers. Compulsively abstract and addictive, an Eggleston plays like a good hook.

A photograph of Eggleston’s from 1985 featuring a Leica resting near a reel-to-reel encapsulates two means for registering our perception of the world. “Of our five senses, we’ve only worked out how to record two: sight and sound,” Sara Knelman observes in these pages, tracing how the camera has continuously chronicled the phonograph, from a young Edison proudly posing with his new invention in 1878 to contemporary artists who make vinyl a subject of their work. With the advent of digital audio, the analog endures and LP covers, at twelve inches tall, continue to tell their own history of photography. As Vince Aletti, a disco writer turned photography critic, notes, a cover is “sometimes more memorable than the music it helps to deliver.”

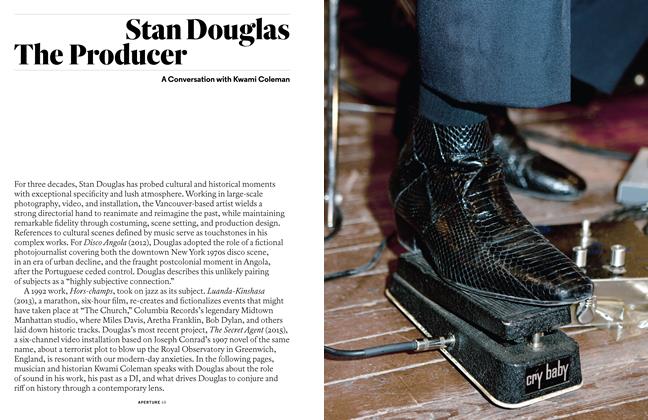

But when the music stays with you, it’s indelible. Before turning to photography and video installation, Stan Douglas moonlighted as a DJ, a past that shapes his films and photographs reprising jazz history, New York disco, and the golden era of Columbia Records.

“The recording mechanism, just like a photograph, captures what we don’t intend,” Douglas notes in a conversation with the musician and historian Kwami Coleman. “We hear sounds we didn’t realize were there.”

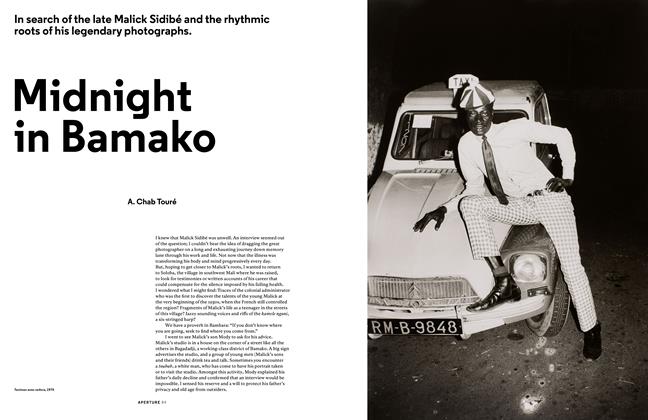

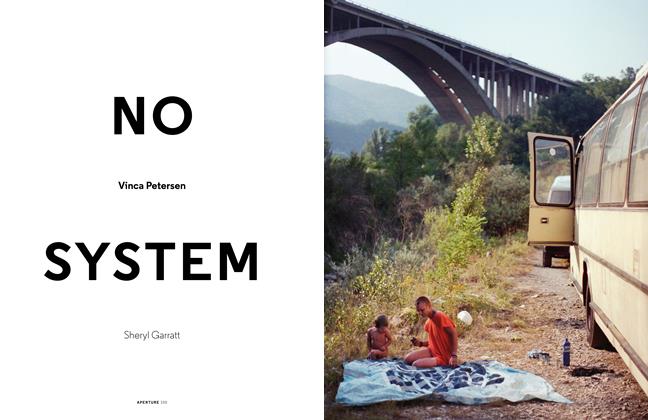

Recorded music moves a crowd, creates a culture, defines and, much like a photograph, freezes a moment. The great Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, who died as we were working on this issue, captured the vivacious nightlife of 1960s and ’70s Bamako, when the French were gone but Western influences, including James Brown 45s, remained. Katsumi Watanabe traversed late-night Tokyo in the early 1980s and witnessed a youth culture of misfits and outsiders dancing all night in the seedy Shinjuku district. A decade later, Vinca Petersen documented Europe’s transient rave culture and roving communal “sound systems,” perhaps the last moment when it was truly possible to go off the grid. More recently, Michael Schmelling turned his lens on Chicago’s rich music scenes, from gritty basement punk shows to thumping hip-hop clubs. Photography might be a silent medium, but in recording the experience of sound, these images turn up the volume.

The Editors

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsListening For Eggleston

Fall 2016 By John Jeremiah Sullivan -

Pictures

PicturesMichael Schmelling Your Blues

Fall 2016 By Kelefa Sanneh -

Words

WordsStan Douglas The Producer

Fall 2016 By Kwami Coleman -

Words

WordsMidnight In Bamako

Fall 2016 By A. Chab Touré -

Pictures

PicturesNo System Vinca Petersen

Fall 2016 By Sheryl Garratt -

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Editors

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAnsel Adams

Summer 1984 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteWestern Spaces

Spring 1985 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteCultures In Transition: The World’s Reality

Early Summer 1990 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteSpecimens And Marvels: William Henry Fox Talbot The Invention Of Photography

Winter 2000 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

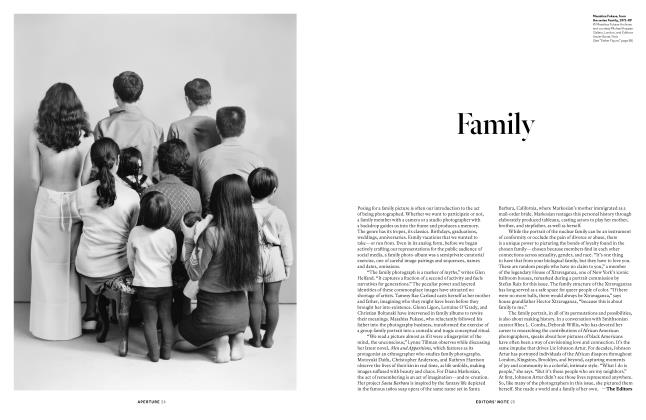

Editor's NoteFamily

Winter 2018 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteEarth

Spring 2019 By The Editors

Editor's Note

-

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteEditors' Note

Summer 2003 By Melissa Harris -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteWitness To Crisis

Fall 1987 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NotePhotostroika: New Soviet Photography

Fall 1989 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteCuriosity

Summer 2013 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteFilm & Foto

Summer 2018 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

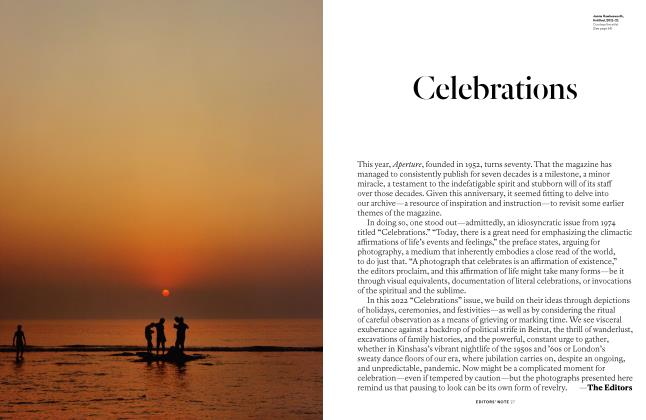

Editor's NoteCelebrations

SPRING 2022 By The Editors