Thomas Dworzak Instagram Scrapbooks

Joanna Lehan

Photojournalist Thomas Dworzak has hitchhiked around Chechnya to cover conflict there, waded through a devastated New Orleans in the aftermath of Katrina, and embedded with U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. But to make his new series of self-published books, he stayed home. The Magnum member, now based in Tbilisi, where he covers the modernization of post-Rose Revolution Georgia, has a consuming side-project: mapping the terrain of Instagram, or at least its more obscure avenues.

Each of his nine “scrapbooks,” produced through Blurb (a self-publishing platform), in editions of five, is dedicated to a particular Instagram hashtag, or related group of hashtags, and each is composed of screenshots from brief windows of time, primarily in 2013. All the images he used were viewable by the public; Dworzak was not required to become a “follower” of any of these users to see them.

The project began when Dworzak became curious about the way Instagram photos provide an inside view into news and global cultures that photojournalists cannot feasibly obtain. Certain hashtags simultaneously offer a rather startling view of the self-absorption of the Instagram generation. Navel-gazing is literally the subject of #siberianwintersarebrutal, which comprises sexy selfies of Russian and northern European youths inside tanning beds. #rkoi, an acronym for Rich Kids on Instagram, is a parade of young people and their bling. This book includes selections from the stream #receiptporn, a hashtag used by louche partiers who post evidence of their weekend sprees, competing to see who spent more.

In #freejahar, Dworzak plucked screenshots from the pseudonymous hashtag as well as others that appeared during the two-week period following the capture of 19-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnaev (nicknamed Jahar), surviving suspect in the Boston Marathon bombing. Declaiming Tsarnaev’s innocence, presumably swayed by his incongruous “cuteness,” teenage girls posted images of the words “free Jahar” written on their hands and forearms. This meme metastasized; the phrase also appeared painted onto fingernails, and cleavage, in more than one instance. There are more disturbing examples of callowness in other books: #auschwitz compiles photos of European teens during class trips to the concentration camp, smiling together as they travel on trains there, or offering the now-classic “duckface” pout.

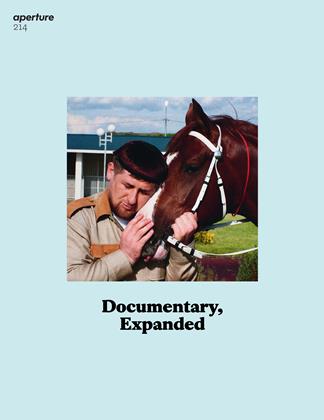

Lest Instagram seem an exclusively adolescent occupation, other volumes provide unparalleled political perspective by unexpected participants. #dprk was the stream of someone at the North Korean embassy in Berlin, and it provided a rarified space for international dialogue, however bizarre. In it we see photos, apparently current, that celebrate a modern North Korea, along with viewers’ comments that range from naive to xenophobic and the poster’s blindly nationalistic responses. #K.R.A. and related hashtags show the often entertaining photos of Ramzan Akhmadovich Kadyrov, the head of the Chechen Republic, chronically criticized for human rights abuses. In them, the thirty-seven-year-old leader smiles while nuzzling animals or working out. Military settings appear, but so do his many children and sports cars, and there are cameos from actor Gerard Depardieu, with whom he seems cozy, as well as Jean-Claude van Damme.

Dworzak’s use of an iPhone and a computer to make screenshots of fleeting events in cyberspace, as opposed to a camera in the “real” world, is not as much a departure for him as one might imagine. He has often used other media as a reflection of his own photography. His most popular book, like this new project, is not focused on his own images at all, but was a collection of photographs of the Taliban that he discovered in an Afghan photo studio. The beautiful hand-painted portraits were shocking for several reasons, including the air of homoeroticism they exude when viewed in a Western context, and the fact that the Taliban famously banned photography.

With this new nine-volume examination, Dworzak obliquely reflects the current sociopolitical climate in the U.S. and far beyond. His decades of experience shooting in conflict zones were ample preparation for this task: to tell the story he found on Instagram, he had to be present, and move fast.

Joanna Lehan recently co-curated A Different Kind of Order: ICP’s Triennial, at the International Center of Photography in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

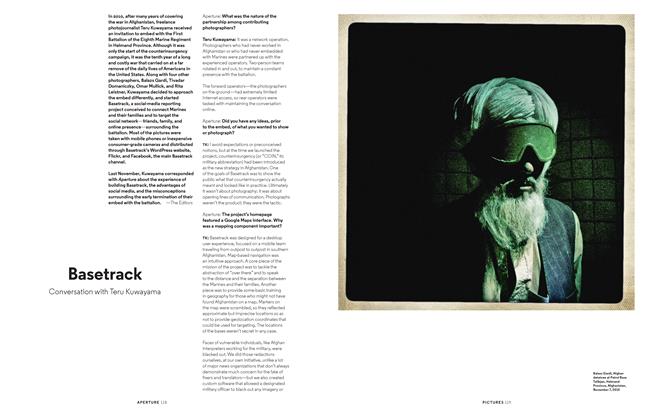

PicturesBasetrack

Spring 2014 By The Editors -

Pictures

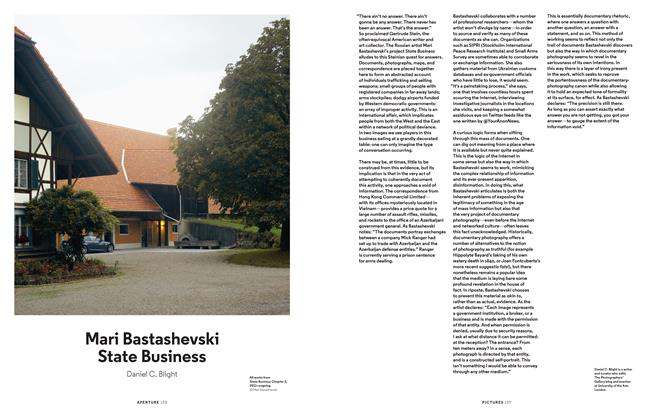

PicturesMari Bastashevski State Business

Spring 2014 By Daniel C. Blight -

Pictures

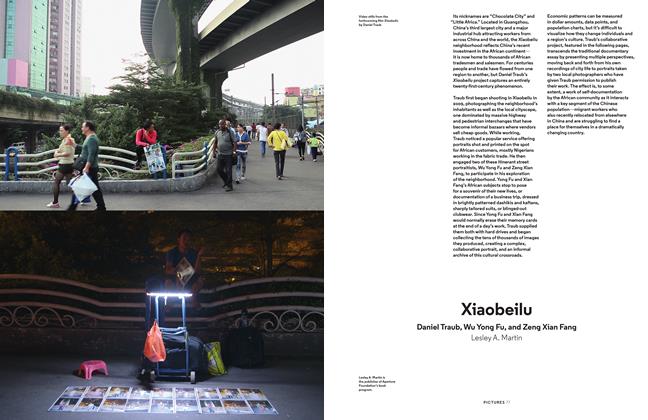

PicturesXiaobeilu

Spring 2014 By Lesley A. Martin -

Pictures

PicturesWe're Talking About Life And Culture

Spring 2014 By Wendy Ewald, Eric Gottesman -

Pictures

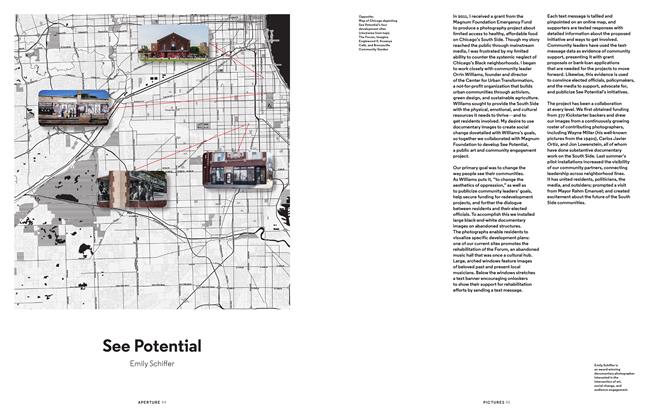

PicturesSee Potential

Spring 2014 By Emily Schiffer -

Words

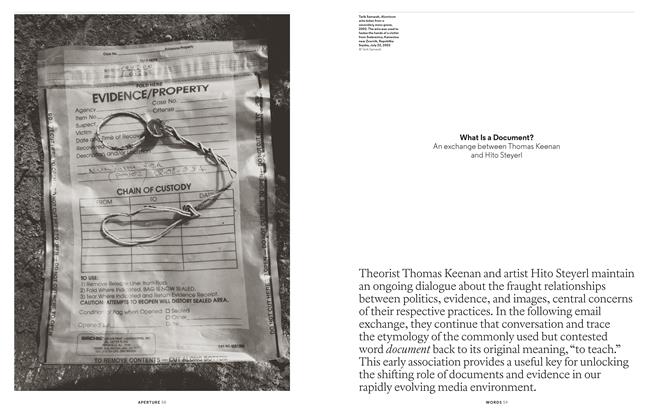

WordsWhat Is A Document?

Spring 2014 By Thomas Keenan, Hito Steyerl

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Joanna Lehan

Pictures

-

Pictures

PicturesMan Of The Twentieth Century

Spring 1980 -

Pictures

PicturesPaul Mpagi Sepuya

Summer 2019 -

Pictures

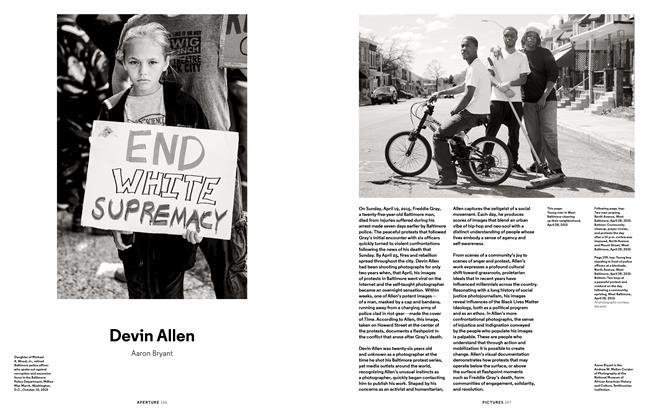

PicturesDevin Allen

Summer 2016 By Aaron Bryant -

Pictures

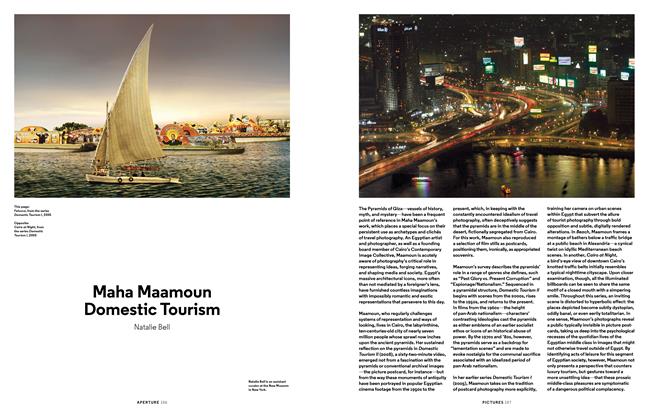

PicturesMaha Maamoun Domestic Tourism

Spring 2016 By Natalie Bell -

Pictures

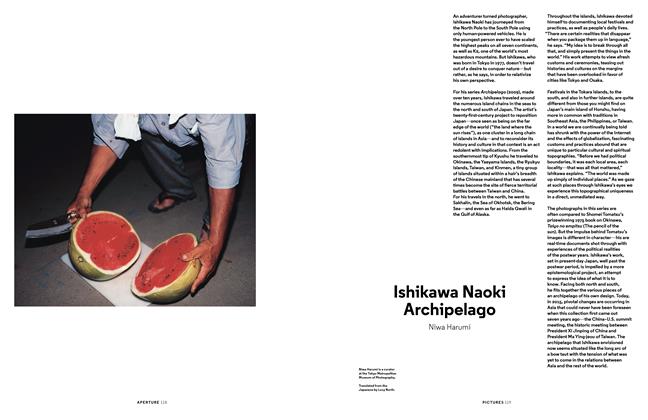

PicturesIshikawa Naoki Archipelago

Spring 2016 By Niwa Harumi -

Pictures

PicturesWe're Talking About Life And Culture

Spring 2014 By Wendy Ewald, Eric Gottesman