Words

For The Camera

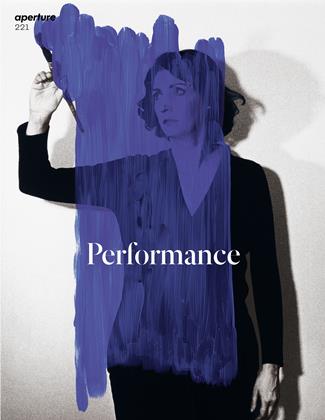

Posing, role-playing, or staging a tableau: the impulse to perform before the lens has been a fixture of photography from the beginning.

Winter 2015 Simon BakerWords

For the Camera

Posing, role-playing, or staging a tableau: the impulse to perform before the lens has been a fixture of photography from the beginning.

Simon Baker

From the first days of the first photographs, those taking the pictures and those being pictured were fully aware of the performative potential of the new enterprise. Consider the strangely stilted tableaux that William Henry Fox Talbot arranged on the grounds of his home, Lacock Abbey, in the 1840s: his friends and family posing as, well, friends and family, but nevertheless acting their own roles as best they could in bright sunlight under the cold eye of the camera. These, surely, were some of the first people ever to “pose” as themselves, as countless others have done for the camera ever since. But as well as performances aimed at the representation of some kind of natural life, there are also, in the earliest photographic experiments, something that we can recognize today as truly performative works.

Perhaps the earliest of these coincided with the 1839 advent of the medium: Hippolyte Bayard produced Le Noyé (Self-portrait as a drowned man) in October 1840. A direct positive print on paper (and therefore an easier and cheaper alternative to the metal daguerreotype), Bayard’s self-portrait is not only a technical masterpiece but a conceptual one. It shows the inventor of the process, slumped as though sleeping, naked from the waist up, like Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 painting of the assassinated Marat; Bayard’s strangely dark hands a testament to both chemistry and hard work, crossed in peaceful resignation on his lap. But it is the title that completes the work, referring the viewer (whomever Bayard imagined that might have been) to the hopeless plight of the sitter: Bayard claimed to have invented photography before Daguerre, who received all the credit for the invention.

In the photograph, he appears rejected, ignored, sinking without a trace below the high watermark of Daguerre’s fame and fortune. Bayard’s silent protest is probably the earliest, and certainly the greatest, of the first real performances made purely for the camera, and existing only as a photographic print.

There is, however, an umbilical cord of radical creativity linking this early moment in photographic history with all that followed, in which the self-portrait tends toward fantasy. Think, for example, of F. Holland Day’s incredible serial self-portrait The Seven Words (1898), in which the artist presents himself not simply as martyred (like Bayard) but as Jesus Christ, crowned with thorns and enduring the agony of the crucifixion to illustrate the final words spoken from the cross. Part of a truly epic project to photograph the life of Christ in which Day took the title role (starving himself in order to do so), Day’s Seven Words can be seen as both spiritual and blasphemous in equal measure. For although Day and his more enlightened critics, Edward Steichen included, saw this work, and indeed the project from which it was drawn, as a sacred enterprise, it was (and remains) a controversial photographic performance, decades ahead of the better-known role-playing conceptual practice that it appears to anticipate.

The ways in which the performative nature of photography and the photographic nature of performance are interrelated and intertwined will be the subject of an exhibition at Tate Modern in February 2016. This article, then, constitutes an initial attempt to walk (and blur) the line between the photography of performance and performative photography, circling around the question of when a photograph records a performance versus when a performance depends entirely on the photographic act, aiming not to present a hierarchy but instead to raise questions about the symbiosis at the heart of an apparent opposition that runs through the medium from its inception to the present day.

Consider performances at which a photographer happened to be present: there is much to be learned about the photographic potential in what only appears to be the subordinate role of the photographer. Harry Shunk and János Render, or ShunkKender, as they are known, started out as photographers in the conventional sense (on the streets of Paris and Berlin) but then went on to become perhaps the most important official witnesses of a broad range of artistic practices, from Yves Klein’s Anthropometries in 1950s Paris to the myriad performances of a generation of artists working in New York in the ’60s and ’70s. There are many examples of the straightforward documentation of performances by figures like Eleanor Antin, Yayoi Kusama, and Marta Minujin (to name just three) but also more complex situations in which Shunk-Kender either become active participants in the events, eliciting poses or demonstrative acts, or even making the works themselves, as is the case with Klein’s i960 Leap into the Void, which was collaged together from two negatives to produce the artist’s legendary (and illusory) dive off the side of a house (see page 43). Elsewhere there are dramatically posed portraits, like those showing the artist Niki de Saint Phalle in 1961, gun in hand, both facing the lens and in profile, but not actually, as it happens, making one of her Feu à Volonté (Shot canvases), which resulted from that particular performative process.

More fascinating still are those moments in Shunk-Kender’s work when they begin with a “document” of an act (a live performance by Yves Klein or Merce Cunningham), then transpose this material, in the darkroom, into something else entirely. Such photographs have a relationship to performance that is like that of an amplified echo to an original sound: related, for sure, but absolutely distinct and different in tone and resonance. In one of the most dramatic examples of their practice, Shunk-Kender solarized the forms of Cunningham’s dancers (performing Nocturnes in Paris in 1964) almost to the point of abstraction, until the precisely choreographed figures from a real performance became merely glowing bodies of light; entangled, entwined, and yet perfectly balanced as photographic compositions.

Beyond the history of photographing performances as such, the relationship among these terms is transformed by a shift along the scale from photographers making photographs of performances to performers making work for, and with, photographers. Once again, it is possible to trace this kind of practice to the early years of photography: think for example of the stunning series of images of the mime Charles Deburau, whose Pierrot found himself not in the theater, nor even on the street, but instead acting out the range of his expressions— 'surprise,” “laughter,” “pleading,” and so on—for the camera of Adrien Tournachon, brother and, briefly, business partner of French practitioner Nadar, perhaps the greatest studio photographer of the mid-nineteenth century. Bringing the actor into the studio, for a performance that was only ever destined to result in a photograph but existed nevertheless in direct relation to a series of performances “off-camera” (in the career of the subject), ushered in one of the richest and most consistent seams of gold in the Nadar story. For, from the 1850s to the studio’s end under Nadar’s son Paul in the early twentieth century, a stellar array of Parisian actors and actresses, Sarah Bernhardt being the most celebrated and frequently photographed, would be called upon to reconstitute their roles (with costumes, sets, and cast) for just a few moments before an audience of one lens in the Nadar atelier.

Such photographs have a relationship to performance that is like that of an amplified echo to an original sound: related, for sure, but absolutely distinct and different in tone and resonance.

While Nadar’s move was to transpose a performed scene from the theater to the more precisely lit tranquillity of his studio, elsewhere the drama (and the collaboration) shifts in the other direction. Perhaps the most important and truly collaborative photographic performances of the twentieth century are those made by and with Eikoh Hosoe in Japan in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Indeed Hosoe’s masterpiece, the 1969 photobook Kamaitachi, is one of the few examples of the genre (or indeed any similar art form) in which both the photographer and the subject are equally credited: “Photographs: Eikoh Hosoe, Performance: Tatsumi Hijikata.” In Kamaitachi, Hijikata, the founder of the butoh dance movement, takes his act into the open spaces of rural Japan in an epic series of set pieces captured as a sequence of single images by Hosoe. Less known, but equally important, is a similar collaboration with the actor Simon Yotsuya. Made in 1971 but never shown until the publication of the book Simmon: A Private Landscape in 2012, this key Hosoe work, like Kamaitachi, is an example of an almost unique hybrid form. The story is acted and posed by Yotsuya across the limits of fact and fiction, opening with an image in which the actor is shown applying his makeup in the shadow of a train station. This set piece inaugurates a whole gamut of games, dramatic poses, and physical expressions of emotion by Yotsuya, which are transformed by his collaboration with Hosoe through the double logic of the photographic series and sequence.

As such, Yotsuya is able to offer something impossible on the stage, a cumulative performance, each image working with those that precede and follow it like the storyboard for a film, albeit each “frame” having been perfectly composed through the restrained poetry of Hosoe’s pictorial approach. Hosoe is probably unique in this level of evenhanded collaboration, the result of an obsession with dance and theater coupled with his unique sensitivity to the fact that photography is essentially always a performative act.

Nadar’s move was to transpose a performed scene from the theater to the more precisely lit tranquillity of his studio.

The collaborative potential of the photographic performance is evident too in the work of contemporary artists like Erwin Wurm, whose One Minute Sculptures are both “produced” as finished works and at the same time seem to encourage viewers to “try this at home,” or at least in the gallery. Wurm’s playful repurposing of objects like buckets, biro pens, and fruit transforms them into ludic bodily adornments and pointless physical supports: a figure parallel with the floor, balanced on a carefully arranged group of oranges. But far from the complex and often dangerous experiments of suburban home-sculptors— in which category we might find upstate New York-based artist Les Krims setting fire to things or arranging nude models in awkward positions in the 1970s—Wurm instead proposes poses that are more often uncomfortable rather than implausible or improper, playing games not only with his subjects (who have included, surprisingly, the model Claudia Schiffer) but with notions of conventional decorum associated with posing for the camera.

Two other photographic works that engage notions of performativity and propriety, albeit in very different ways, are contrasting uses of the strip by artists Hannah Wilke and Jemima Stehli. Wilke’s classic 1976 film performance Through the Large Glass sees the artist stripping slowly and deliberately in a series of freeze-frame poses behind (and through) Marcel Duchamp’s seminal transparent sculpture, but in fact it is just one of a number of calculated strips that began with a live performance in November 1974. A second version of the same work from the same year, produced specifically “for the camera” as a sequence of photographs and titled Super-t-Art, shows the progress of Wilke’s single prop/garment, a white sheet, from an initial toga-like shift through a series of symbolic revisions (simultaneously a form of strip) that concludes with a biblical wrap and pose directly referencing Christ on the cross. Stehli, a British artist who came to prominence in the 1990s, assumed a stance similar to Wilke’s, taking a counterposition to the dominant language and forms of feminist practice and the associated articulations of the desiring male gaze; she produced her own Strip series (1999-2000), this time with the complicity of a select group of male viewers. Stehli’s strips (also sequential photographs) show curators, writers, and critics from the London art world in the act of taking self-portraits—using the artist’s camera in a neutral studio setting—while Stehli strips with her back to the camera but facing her male “sitters.” The results are uncomfortable and comedic, with the artist’s performance being both the reason for the photograph (in terms of her own self-image-based practice) and an obstacle to the person nominally in control of the process of simultaneously picturing themselves.

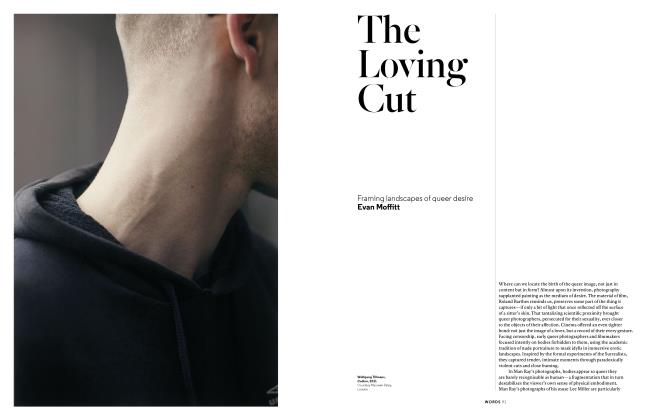

The critical language of the performative self-portrait is so broad and, at this point, so familiar as to be almost impossible to summarize, but there are still some important and often overlooked contributions to the field, especially in terms of the politics of identity, from key historic works like Linder’s She/She (1981), Adrian Piper’s Foodfor the Spirit (1971), or any of Hans Eijkelboom’s works of the early ’70s to recent projects like Samuel F osso’s African Spirits (2008) and Tomoko Sawada’s ID series (1998-2001). But beneath the more readily visible ongoing practice of interrogative self-portraiture there remains the submarine terrain first explored by Bayard in 1840. Interest in this, too, can be traced in contemporary work, most notably Masahisa Fukase’s incredible 1991 project Bukubuku (although it should be said that Fukase is more waving than drowning). Named for the Japanese onomatopoeia for the sound of bubbles, Bukubuku is a series of seventy-nine self-portraits the artist made entirely in his bathtub: clothed, naked, smoking, spouting, sinking, fractured by the symmetry of the waterline. Fukase’s work is both a playful virtuoso gesture (working with the lens at its limit) and a deeply personal work exploring isolation and loneliness, a strange merman’s pendant to his better-known study of depression, the 1992 book The Solitude of Ravens.

The critical language of the performative self-portrait is so broad and, at this point, so familiar as to be almost impossible to summarize.

Fukase spent much of the early part of his career photographically documenting the life and activities of his immediate family, with extended bodies of work like Yohko (1978) and The Family (1991). But with Bukubuku, he ends up turning the camera back on himself, only to shy away from a searching self-examination via the self-portrait in favor of an extended game of smoke and mirrors. Fukase, then, at the end of the twentieth century, leaves us pretty much exactly where we found Bayard early in the nineteenth: wondering at the expressive potential of the camera in the hands of someone willing to perform for it.

Simon Baker is Senior Curator, International Art (Photography), Tate, London. The upcoming exhibition Performing for the Camera will be on view at Tate Modern February 18June12,2016.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

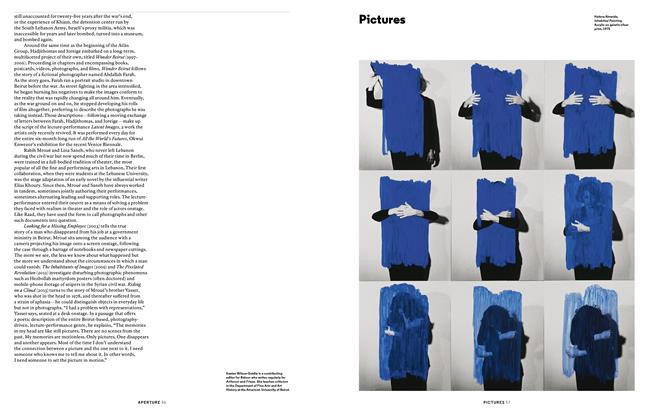

PicturesHelena Almeida

Winter 2015 By Delfim Sardo -

Pictures

PicturesMorgan On Graham/ Mangolte On Brown

Winter 2015 By Kristin Poor -

Pictures

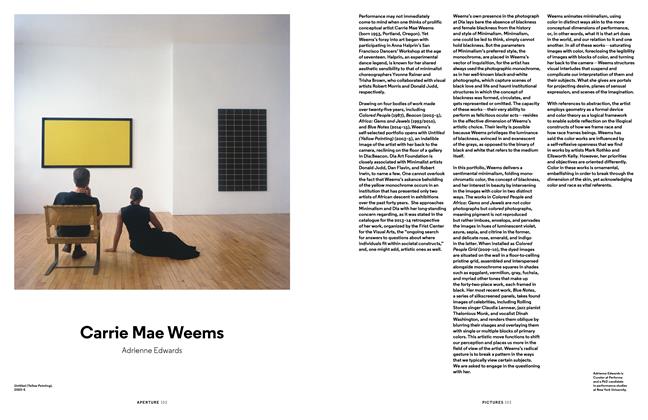

PicturesCarrie Mae Weems

Winter 2015 By Adrienne Edwards -

Pictures

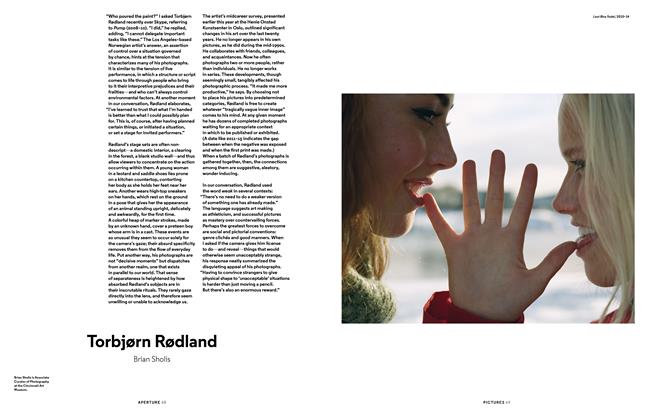

PicturesTorbjørn Rødland

Winter 2015 By Brian Sholis -

Pictures

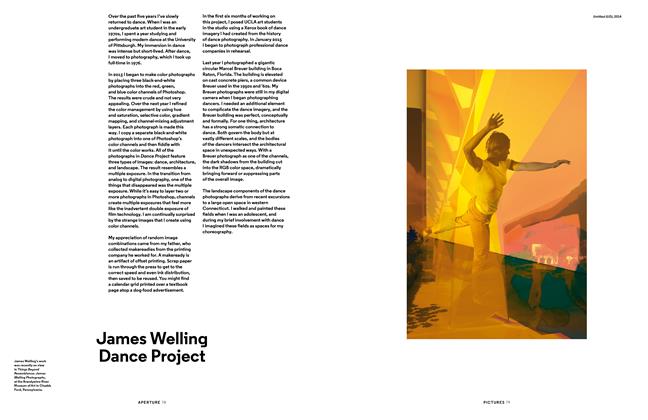

PicturesJames Welling Dance Project

Winter 2015 -

Words

WordsOn Record

Winter 2015 By Roselee Goldberg, Roxana Marcoci