JEROME LIEBLING

REVIEWS

In 1948, at the ripe age of twenty-four, Jerome Liebling was well along on the intertwined paths that would designate the shape of his life: photography and filmmaking. He had begun by studying art and design at Brooklyn College with Ad Reinhardt and Burgoyne Diller; he then joined the Photo League, where he associated with several of its luminary members, among them Paul Strand (with whom he studied), W. Eugene Smith, Lisette Model, and Aaron Siskind; and at the New School for Social Research he had taken courses in film production with Arthur Knight, Raymond Spottiswoode, and Leo Hurwitz.

Last summer’s exhibition of Liebling’s photographs at the Currier Museum of Art in Manchester, New Hampshire (organized by the museum’s director of exhibitions, P. Andrew Spahr), testified to the interdependence of these two callings. Never timid about trying out new photographic strategies, in 2009 Liebling began a collaboration with master printer Jonathan Singer in Boston; together they revisited negatives of Liebling’s images from 1947 to 1996, which Singer scanned with an ultra-high-quality flatbed scanner, then creating glorious new prints at monumental sizes—some more than three feet across. It is easy to see the filmmaker’s eye in operation here, both in the prints’ cinematic new scale, and in their conception as narratives: each contains a tale to be recognized and protracted.

In 2006 Liebling told the New York Times that one of his photographic mandates from the start has been to “go figure out where the pain was.” He has always had a conscientious and intrepid drive to look frankly at subjects that some might find hard to take: consider his 1950s slaughterhouse interiors populated with blood-spattered workers and dangling animal haunches and heads; his 1960s examinations of dismal state-run institutions and clinics; his 1970s studies of disintegrating cadavers (these last not shown at the Currier). In the brochure that accompanies this show, Liebling is asked about the choice he made some thirty years ago to move from black and white to color. His succinct reply: “It’s the same pain.”

But with that compassionate desire to come to terms with pain, there is another kind of empathy at work in Liebling’s photographs: a humanistic wit and affection for beauty in its varied forms. These elements are evinced in both his black-and-white images and in the color work; in places as far-flung as Miami and Málaga, New York and Jerusalem; in images as cool and calm as Hopper paintings and in others as searing as Goyas.

There is, throughout, a clear compulsion to connect. One of the earliest photographs in this selection, Butterfly Boy, New York City (1949) shows a child of perhaps six, decked out in herringbone coat and cap, communicating directly, fervently with the lens, holding up the sides of his coat like a superhero in mid-change. Nearly fifty years later, in 1996, a Russian girl in New York’s Brighton Beach throws Liebling the same expressive look: neither smiling nor scowling, yet givipng everything up to his lens.

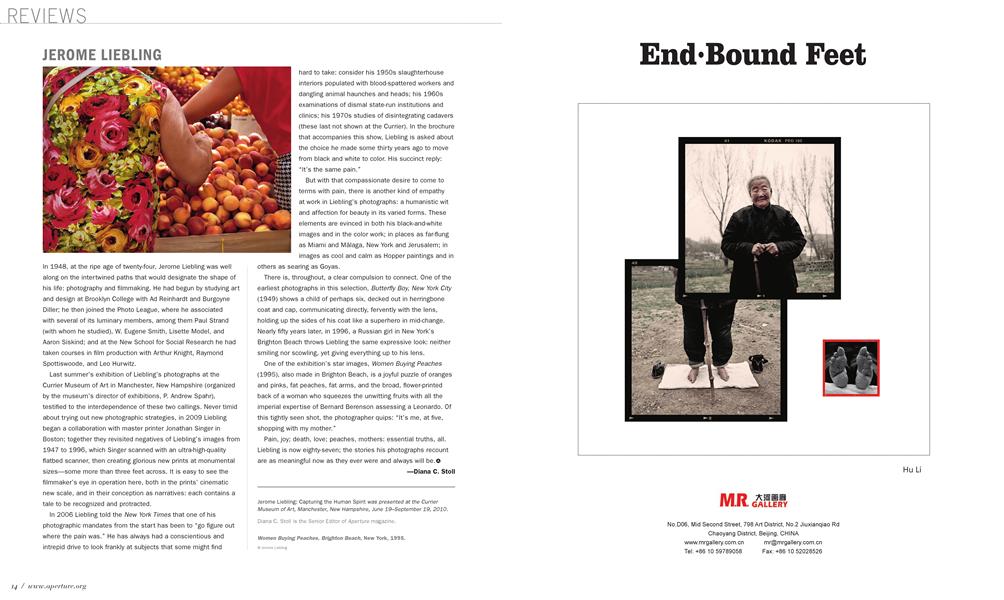

One of the exhibition’s star images, Women Buying Peaches (1995), also made in Brighton Beach, is a joyful puzzle of oranges and pinks, fat peaches, fat arms, and the broad, flower-printed back of a woman who squeezes the unwitting fruits with all the imperial expertise of Bernard Berenson assessing a Leonardo. Of this tightly seen shot, the photographer quips: “It’s me, at five, shopping with my mother.”

Pain, joy; death, love; peaches, mothers: essential truths, all. Liebling is now eighty-seven; the stories his photographs recount are as meaningful now as they ever were and always will be.©

Diana C. Stoll

Jerome Liebling: Capturing the Human Spirit was presented at the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, June 19-September 19, 2010.

Diana C. Stoll Is the Senior Editor of Aperture magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

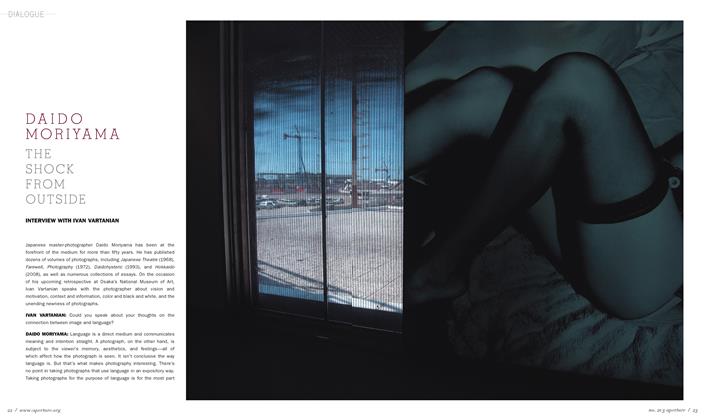

DialogueDaido Moriyama The Shock From Outside

Summer 2011 -

Dialogue

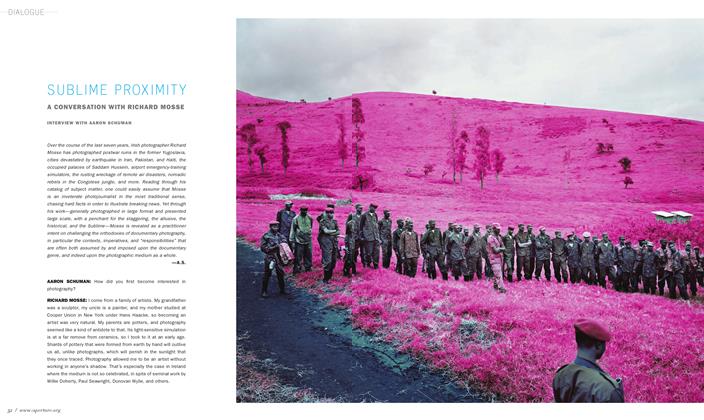

DialogueSublime Proximity

Summer 2011 By Aaron Schuman -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectVenice 1943

Summer 2011 By Paolo Ventura -

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaHans-Peter Feldmann A Paradise Of The Ordinary

Summer 2011 By Mark Alice Durant -

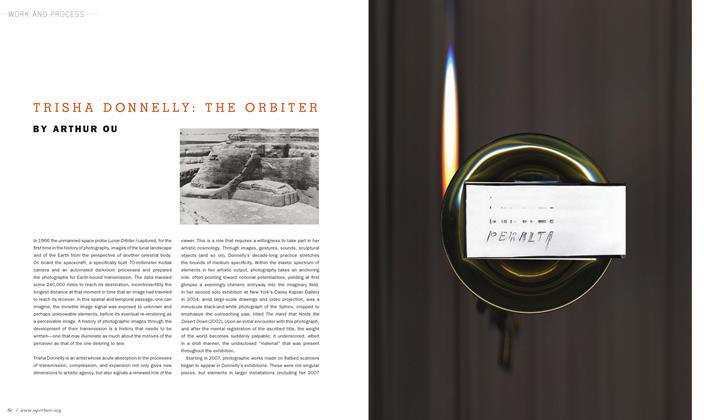

Work And Process

Work And ProcessTrisha Donnelly: The Orbiter

Summer 2011 By Arthur Ou -

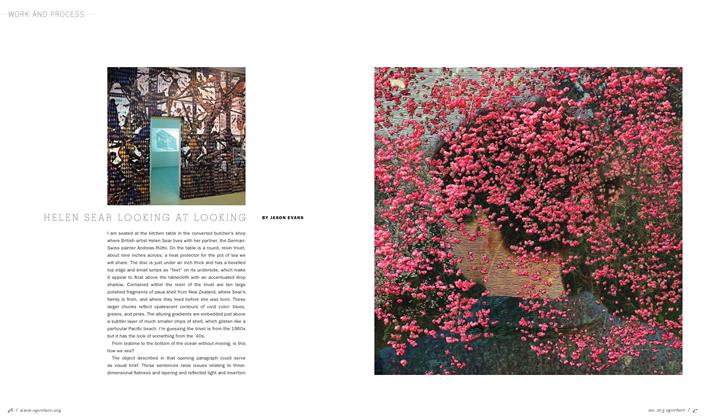

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHelen Sear Looking At Looking

Summer 2011 By Jason Evans

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Diana C. Stoll

-

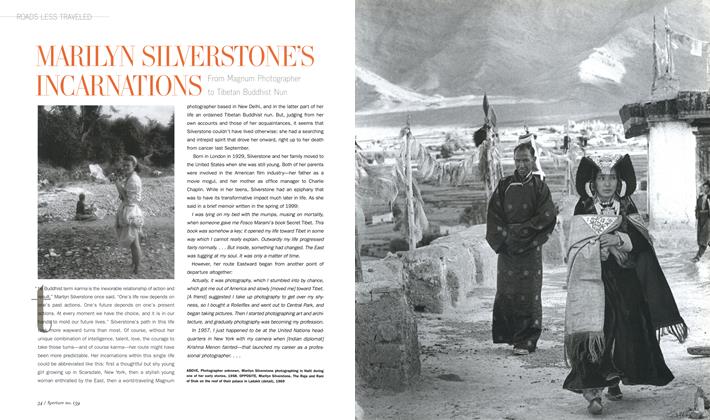

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledMarilyn Silverstone’s Incarnations

Spring 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

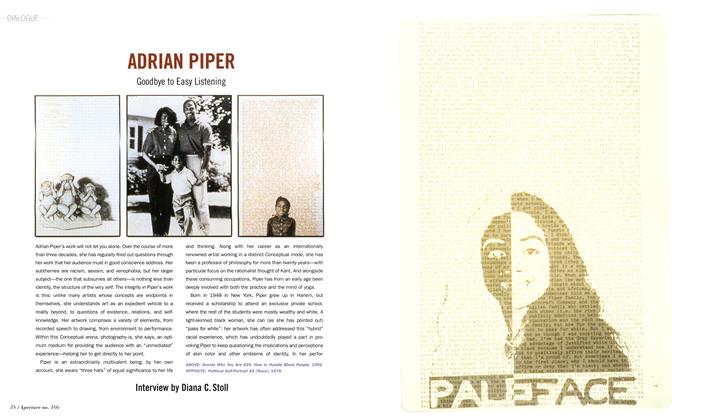

Dialogue

DialogueAdrian Piper

Spring 2002 By Diana C. Stoll -

Remembrance

RemembranceJonathan Williams, 1929-2008

Fall 2008 By Diana C. Stoll -

Remembrance

RemembranceJerome Liebling, 1924-2011

Spring 2012 By Diana C. Stoll -

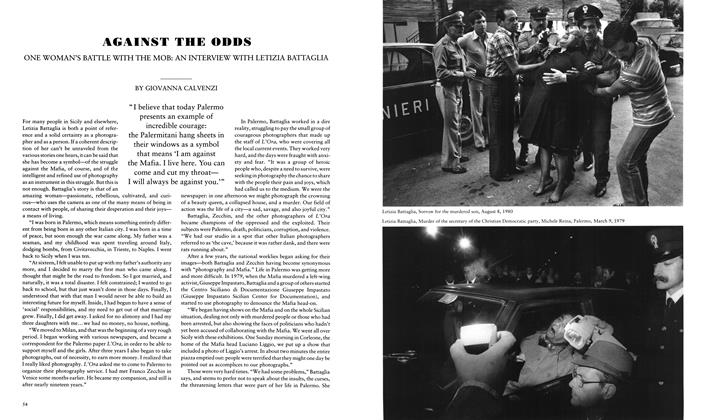

Against The Odds

Summer 1993 By Giovanna Calvenzi -

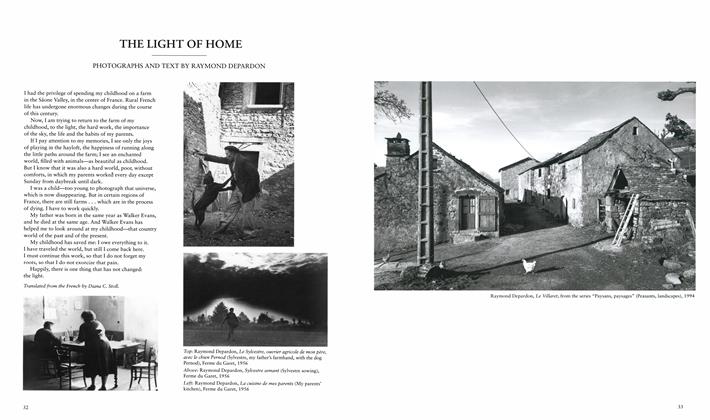

The Light Of Home

Winter 1996 By Raymond Depardon

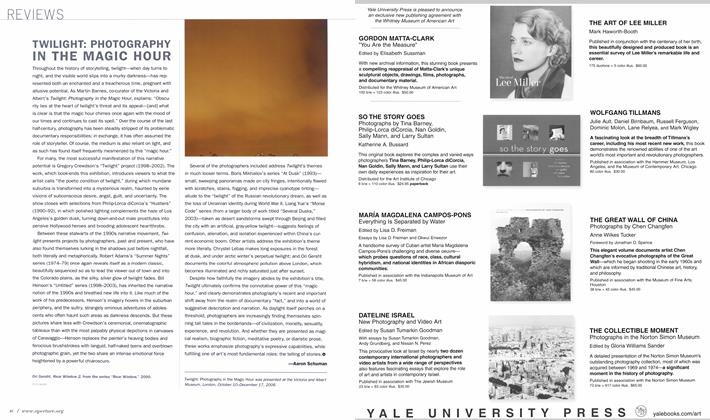

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsTwilight: Photography In The Magic Hour

Summer 2007 By Aaron Schuman -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Pictures Generation

Spring 2010 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Reviews

ReviewsZoe Leonard: Photographs

Fall 2008 By Martin Jaeggi -

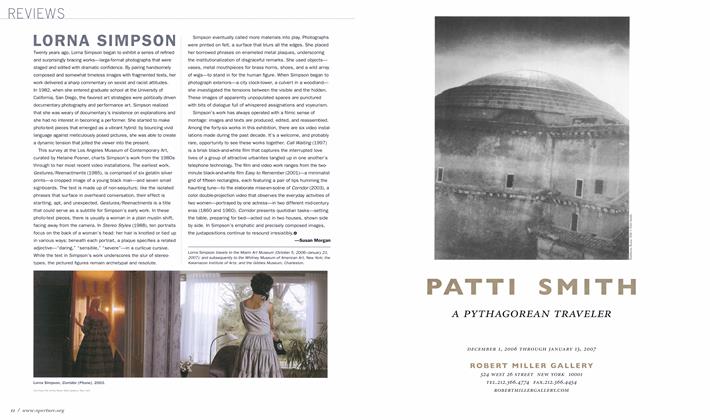

Reviews

ReviewsLorna Simpson

Winter 2006 By Susan Morgan -

Reviews

ReviewsChaos: How Has Photography Changed Our Way Of Looking At Things?

Summer 2006 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsHelios: Eadweard Muybridge In A Time Of Change

Winter 2010 By Vicki Goldberg