Kathya Maria Landeros

West

Sandra Cisneros

Their names are Nicanor, Nato, Adrián, Lupita, Victor, Arturo, Antonia, Cristian. Even without the captions, I can tell the photographer knows who they are. They’re not anonymous props in a wild landscape, not statistics, not "others” to be afraid of. The subjects Kathya Maria Landeros captures are above all presented as people, the land presented in context to these individuals. Her camera lets them tell their own stories.

Landeros documents with deep familiarity California’s Central Valley and those bound to that land by labor. Millennia before European nations entered the New World, commercial routes were already connecting native communities from ocean to ocean, from the arctic north to the southern tip of Patagonia. The people in these photographs, the descendants of the survivors of conquest, land appropriation, and ethnic cleansing, continue to migrate across arbitrary borders, the product of the clash between the European and the native views of land. It is the same earth cultivated over thousands of years, the same routes followed north and south. This continuous thread is Landeros’s visual narrative as well as her own story.

"There are histories we know intimately because we have lived them,” Landeros tells me recently. "I come from a close-knit family from Mexico who came to the United States in search of work, in the canneries, in the fields, cleaning homes, whatever work they could find. Their power was in being unified. If history has shown me anything, it’s that our survival depended on that.”

Landeros lives in a time when the world is divided by borders. She is born on the U.S. side. This makes it possible for a scholarship, and her own intelligence, to launch her to another coast. What if she had been born in Mexico, where the working class create "folk art,” not art? What if she had stayed in the California Valley—would she have worked in the fields? How does an unmarried daughter convince her parents to let her go off to a university, let alone one on the other side of the country?

"Until I went off east to college, art photography was something I didn’t even know about,” Landeros says. "It was storytelling, and poetry, and social activism, and everything I loved rolled into one magical package.”

The irony is that her education does bring her home to work in the fields. One day she accompanies her father to the farm labor camps. She begins to take pictures. "Those were the first photographs I made that gave me a sense of purpose,” she says. "My experience represents so many people in this country, yet in some ways I’m working in a vacuum. Latinos in this country aren’t being represented photographically. Photos of the American West exclude so many people of color.”

The series Verdant Land (2011-13) and West (2011-ongoing) obliged Landeros to follow ancestral paths south and north over a decade. In this contentious moment in history, the stories we tell are a social responsibility. Landeros tells them with humility. And in service. In my opinion, to be of service to those one loves is the highest of the high arts.

Sandra Cisneros is a novelist, poet, essayist, and the author of The House on Mango Street (1984), Caramelo (2002), and A House of My Own: Stories from My Life (2015).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

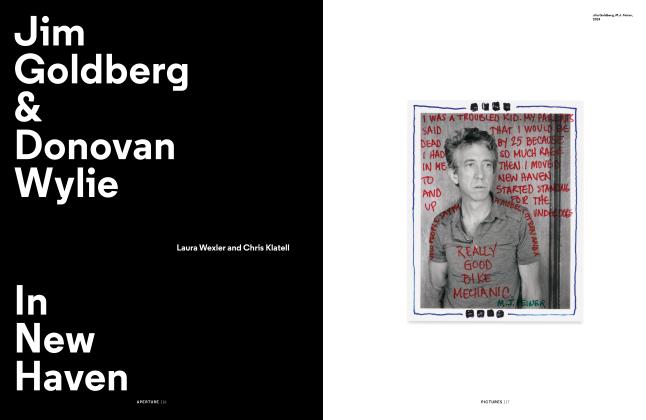

PicturesJim Goldberg & Donovan Wylie: In New Haven

Spring 2017 By Laura Wexler, Chris Klatell -

Words

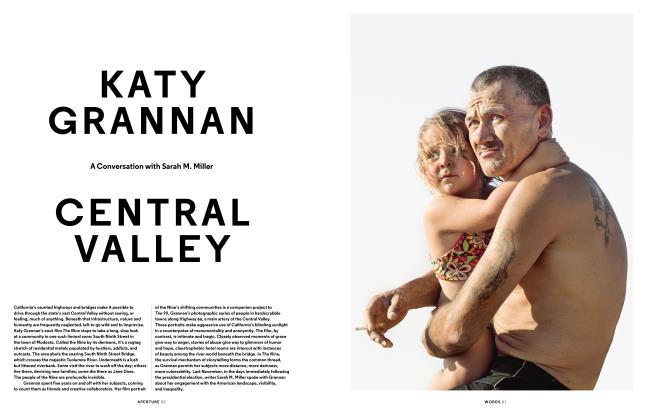

WordsKaty Grannan: Central Valley

Spring 2017 By Sarah M. Miller -

Pictures

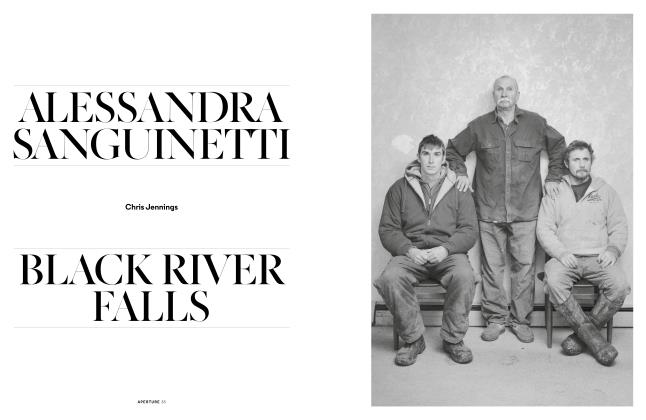

PicturesAlessandra Sanguinetti: Black River Falls

Spring 2017 By Chris Jennings -

Pictures

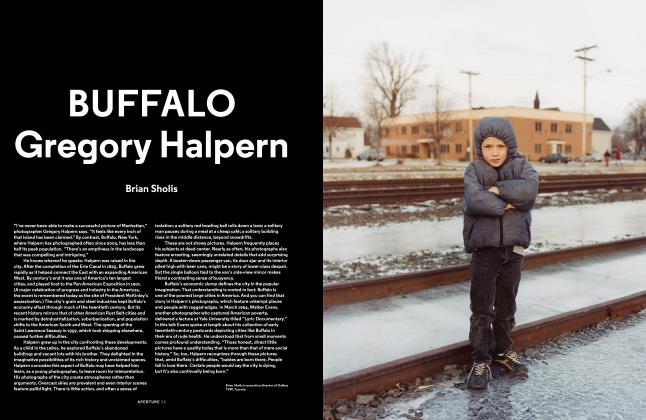

PicturesBuffalo Gregory Halpern

Spring 2017 By Brian Sholis -

Words

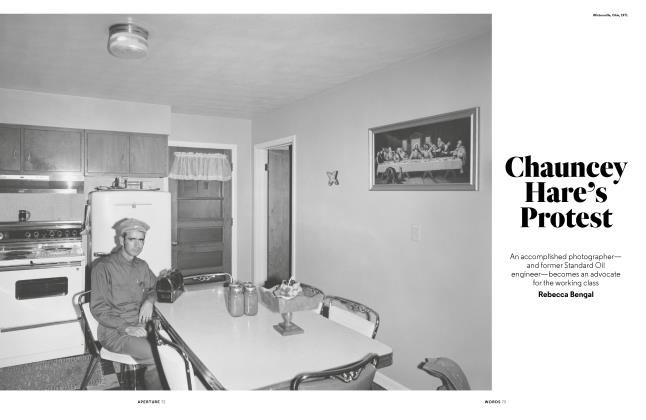

WordsChauncey Hare’s Protest

Spring 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

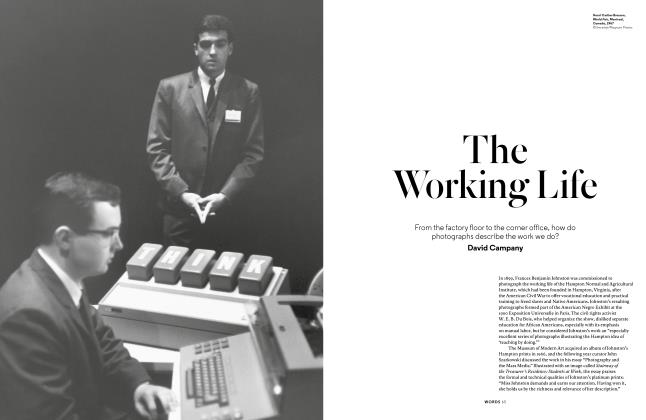

WordsThe Working Life

Spring 2017 By David Campany

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Pictures

-

Pictures

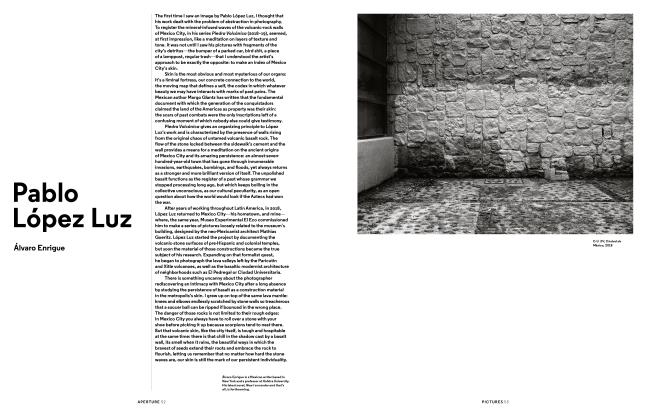

PicturesPablo López Luz

Fall 2019 -

Pictures

PicturesMarianne Wex

Winter 2013 By David Campany -

Pictures

PicturesHelena Almeida

Winter 2015 By Delfim Sardo -

Pictures

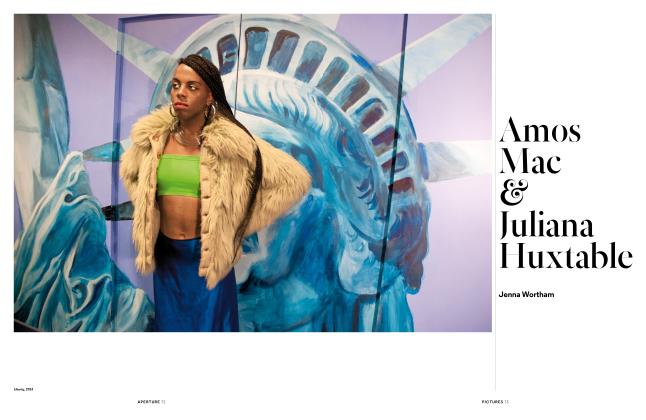

PicturesAmos Mac & Juliana Huxtable

Winter 2017 By Jenna Wortham -

Pictures

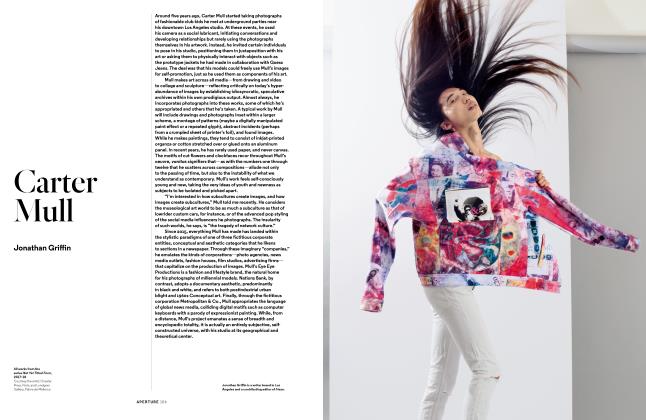

PicturesCarter Mull

Fall 2018 By Jonathan Griffin -

Pictures

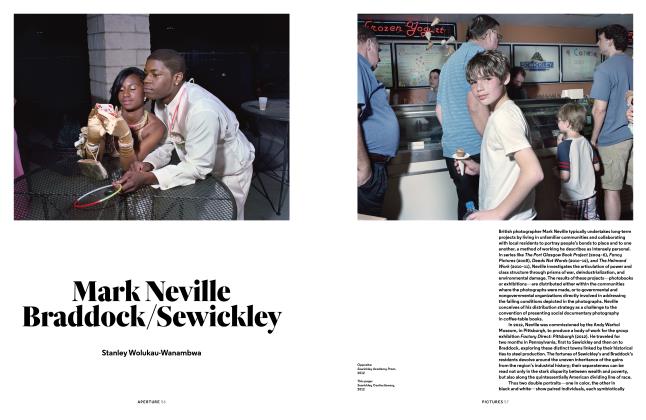

PicturesMark Neville: Braddock/sewickley

Spring 2017 By Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa