Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Twenty minutes into my conversation with Paul Mpagi Sepuya he makes me a diagram. On one end is a drawn figure, representing a photographer, and on the other, a straight line evincing the back of a studio wall. In between, but closer to the wall, is yet another line. This is meant to be a curtain, or a photographer’s backdrop. He labels these points—A (the photographer), B (the backdrop), and C (the wall)—and immediately starts talking about space. There’s the space between the photographer and the backdrop (AB), the slim space behind the backdrop (BC), and the space from the photographer to the back of the studio (AC). His question, although hardly stated as a question to me, is broadly this: Under what conditions do these spaces become visible? And which bodies are implicated, or can be conjured in them?

Much has been written of queer desire in relation to Sepuya’s photographs, and indeed, it is an enduring concern.

Yet, in addition to the affective circuits of desire he portrays, his work over the last ten years reveals a particular spatial attentiveness. Many of these photographs make prodigious use of a studio mirror—to expand or contract space, to give depth or deny it, and to show the possibilities of surface. Gradually, one can usually make out a mirror, a recurring prop in these bodies of work, with its smudges of fingerprints and the skin of previous models. Sometimes it has photographs or images affixed to it. Such a surface, according to Sepuya, "is about grounding the work in the space of its production, and embedding my presence and the presence of others in the making of the work (whether reflection or trace).” His photographs demand thoughtful looking, not only to work out the internal spatial mechanics, but also to revel in his double-helix twists on a classic genre— the studio portrait.

Sepuya, who was born in Los Angeles and returned to the city for graduate school after living in New York for more than a decade, prefers his photographs installed in arrangements of multiple images from the same, or similar, body of work. In 2007, the artist displayed a sequence of portraits of new friends and potential lovers, a series entitled Beloved Object and Amorous Subject, Revisited, on a shelf running around the walls of Envoy Enterprises gallery in New York. The photographs were spaced on the shelf in a way that indicated the social distance or closeness between these networked men. "It was only shown that once,” says Sepuya, "but I had since then hoped that it would be shown more times, each time the sequencing and spacing changing as our friendships and relationships grew and changed.”

Relations with others have always played a part in Sepuya’s practice, but now other artists are included in the mix. In Darkroom Mirror (_2ioo8s) (2017), for example, the artist invited photographer James Garcia into the studio. Sepuya is positioned behind the lens of his camera, adjusting the focus with his thumb and forefinger, which splay out like the petals of a lily in mid-bloom; Garcia stands at his side, setting up a shot with his Rolleicord twin-lens camera. Both men are naked and absorbed in their work. Garcia’s torso and leg function as a fleshy border, his hand pointing the camera ever-so-slightly toward Sepuya. In this photograph, and others like it, Sepuya reckons with his sitter’s multiple identities, as a fellow photographer and as a subject willingly caught in another’s field of vision.

In earlier works, these identities might have been refracted through twentieth-century literature. For example, in Victor, November 21, 2010, a copy of Fire!!, the single-issue Harlem Renaissance literary journal begun by Langston Hughes and a slew of others, dangles off a chair in the bottom right corner.

In Sepuya’s Darkroom Mirror series, one gets the relation to a history of photography, of racial imagining, of queer communal politics—but without an explicit connection.

Whether it’s a studio, a photo lab, or the back room of a sex club, the darkroom is a place of commencement, a site of profound multiplicity, and a space in which life and practice are always already intertwined.

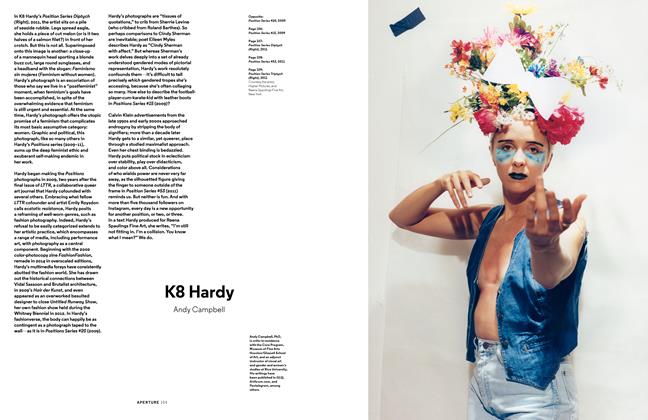

Andy Campbell

Andy Campbell is Assistant Professor of Critical Studies at the University of Southern California Roski School of Art and Design, Los Angeles.

PICTURES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Pictures

PicturesTorbjørn Rødland: Into The Light

Fall 2018 By Travis Diehl -

Words

WordsIlene Segalove’s Modern America

Fall 2018 By Charlotte Cotton -

Words

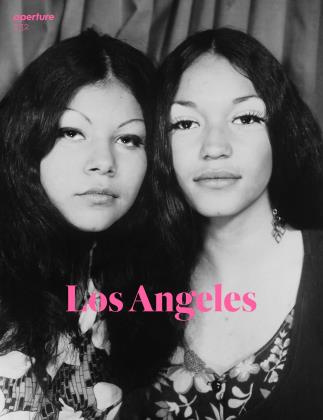

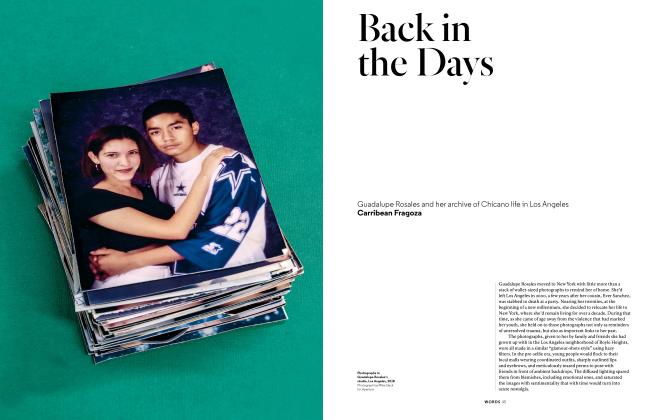

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

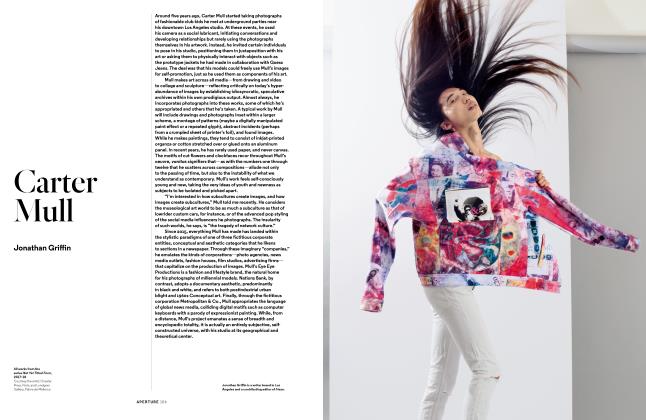

PicturesCarter Mull

Fall 2018 By Jonathan Griffin -

Pictures

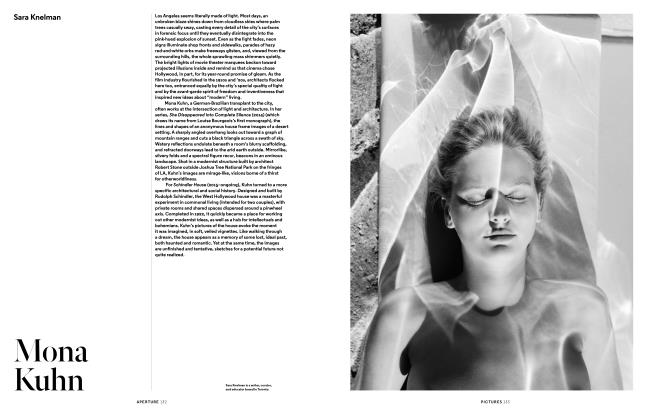

PicturesMona Kuhn

Fall 2018 By Sara Knelman

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Andy Campbell

Pictures

-

Pictures

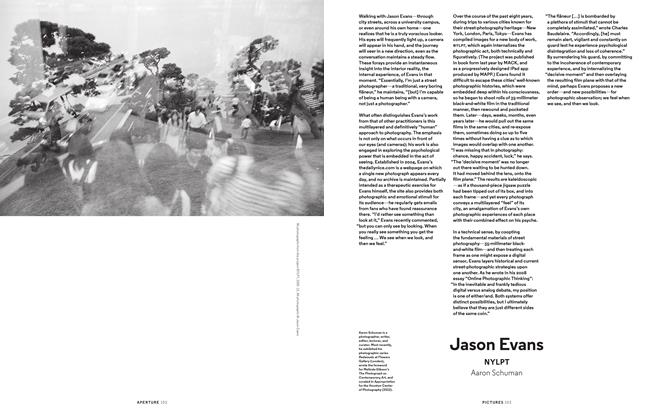

PicturesJason Evans Nylpt

Spring 2013 By Aaron Schuman -

Pictures

PicturesAlex Prager

Summer 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesElle Pérez

Winter 2016 By Salamishah Tillet -

Pictures

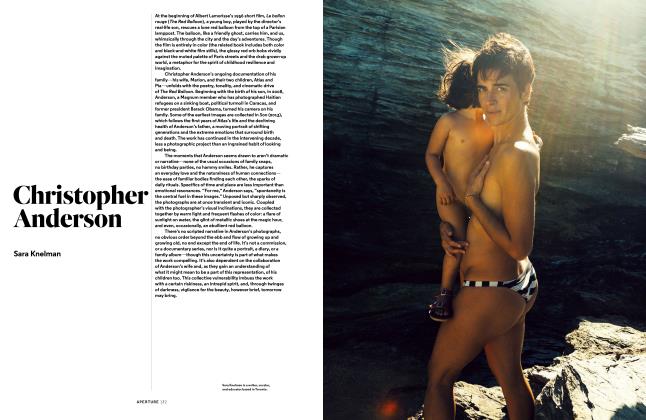

PicturesChristopher Anderson

Winter 2018 By Sara Knelman -

Pictures

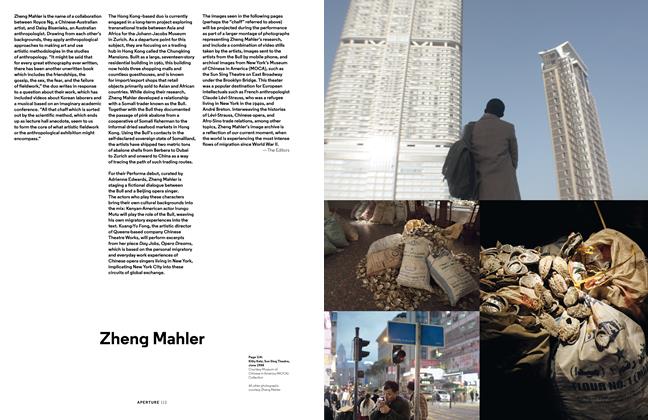

PicturesZheng Mahler

Winter 2015 By The Editors -

Pictures

PicturesClaudia Andujar

Summer 2014 By Thyago Nogueira