Words

Chauncey Hare’s Protest

An accomplished photographer— and former Standard Oil engineer—becomes an advocate for the working class

Spring 2017 Rebecca BengalChauncey Hare’s Protest

An accomplished photographer— and former Standard Oil engineer—becomes an advocate for the working class

Rebecca Bengal

“These photographs were made by Chauncey Hare to protest and warn against the growing domination of working people by multi-national corporations and their elite owners and managers.”

In the summer of 1979, as long lines queued up outside the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for the highly anticipated arrival of Mirrors and Windows: American Photography since 1960, a John Szarkowski-curated exhibition, one man walked in the opposite direction. The show carried with it the electric buzz of a star curator redefining photography for a new age and anointing a current generation of photographers. Szarkowski divided them into two camps. There were the “mirrors,” photographers he categorized as “romantic” and “expressionist,” Robert Rauschenberg, Duane Michals, and Andy Warhol among them. Those in Szarkowski’s “windows” group, whose work he called “realist” (“because no other word was better”), included Garry Winogrand, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Helen Levitt, William Eggleston, and Stephen Shore, as well as a rather intense-looking individual pressing fliers into the hands of passersby, demanding the removal of his own photograph and urging a boycott of the exhibition altogether.

The flier called for outrage at the show’s corporate sponsorship by tobacco giant Philip Morris.

On that day in June, Chauncey Hare was at the pinnacle of his photographic career. Two years earlier he had flown to New York for the opening of The Effects of Technology on the Individual: Photographs by Chauncey Hare, his solo show at the Museum

of Modern Art, curated by Szarkowski. “I heard later that no one expected to see a short, knapsack-carrying, sandal wearing, ex-corporate engineer playing the role of a three-time Guggenheim Fellow photographer,” Hare wrote of his Manhattan experience.

He stayed at the West Side Y but was taken to lavish “expense account meals” with Aperture, who published his first book of photographs, Interior America, in 1978. Two months after Hare picketed Mirrors and Windows, Janet Malcolm reviewed Interior America alongside Walker Evans: First and Last (1978) and a 1978 reprint of Robert Frank’s The Americans (1959), calling Hare’s pictures of working people in their homes and workplaces and towns “devastating.” “He shows us to ourselves,” Malcolm wrote in The New Yorker, her review brilliantly titled “Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Pa.,” “as perhaps no other documentary photographer has ever done.”

“We all thought he was crazy,” Jack von Euw recently recalled of the day he met Chauncey Hare. He was speaking from his office at the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is curator of the pictorial collection, home to Hare’s archives.

“At that time I was an aspiring photographer and most of us would have given our left arm to be in that show. John was the kingmaker.”

When von Euw visited Mirrors and Windows in 1979, he found himself unsettled by the message delivered by Hare and also unable to ignore the presence of Philip Morris, whose name was boldly lettered on the gallery walls. “What did it mean that such a large corporation and one that merchandised cancer as a by-product should sponsor an art exhibition?” von Euw wrote decades later in the afterword to Protest Photographs (2009), Hare’s third book. What seemed an act of self-sabotage in 1979 did not end Hare’s photographic career—he would do that on his own terms—but it did illuminate the current of protest that rises from the core of his pictures. Von Euw tucked Hare’s flier in his pocket and kept it for many years.

Rare is the photographer who desires a mention of personal stories to frame the work; rarer still is the photographer who insists on it absolutely. But in all three books of photographs Hare published, he contributed a substantial and distinct autobiographical essay. His resistance to Mirrors and Windows is the defining moment of his life as a photographer; his awakening, though, occurred more than a decade prior, in March 1968, in Point Richmond, California. Point Richmond is under an hour’s drive from Berkeley and the Haight, but a biopic of the turning point of Hare’s life in the late ’60s would not cue Jefferson Airplane or stock footage of flower children on acid. Chauncey Hare later wrote of meeting Orville England, who would become not only his most pivotal photographic subject but a close friend,

“I was reminded of fairy tale gnomes who ask questions that may determine your fate.” England, a stocky, genial man, approached Hare and asked if he wanted to buy a little plastic camera. How could this stranger have known, Hare wondered, that he had a Leica concealed in his jacket? He accompanied England and his wife Helen home.

Hare, an engineer at the Standard Oil Company, typically roamed the streets, camera in coat, on his lunch break. He had taken

up photography much in the way he had taken up fishing, except in a few years’ time he had gone from shyly shooting landscapes and developing his film in a closet darkroom to making pictures not only with his Leica but also with a large-format view camera.

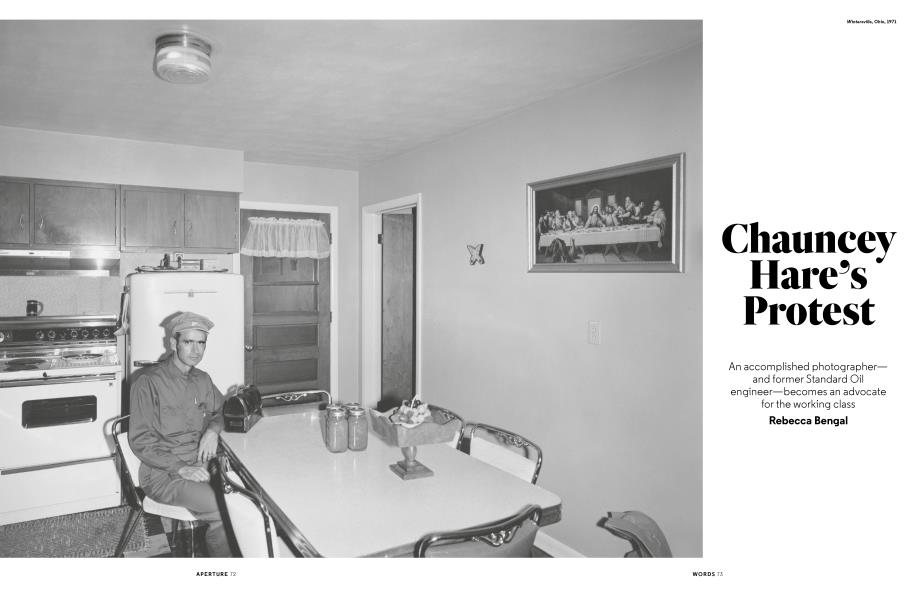

He eventually learned that England, a refinery worker, had become disabled after being exposed to asbestos on the job. Hare’s own grandfather had lost the use of a leg while working at Pittsburgh Steel. Objects and ephemera of England’s home, which Hare returned to photograph the next day, evoked the concrete, household details Hare remembered from summers at his grandparents’ house in Pennsylvania. If Hare was to eventually become the kind of photographer Szarkowski called a “window,” Orville England was the mirror he needed, the reflection of his own life and the omen that would propel it forward. The photograph he made upon his return, of England sitting in his kitchen, was Hare’s first real look into interior America.

Reproductions of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper and paintings of horses and kittens and streams fill the rooms that Hare came to photograph in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, the Sierra foothills, the San Francisco Bay Area, and places in between. Lamps, kettles, coffee cans, telephones, water heaters, blank televisions, and wall mirrors amplify the harrowing effect of his images. He rarely took more than one or two photographs at a time; he arrived bearing letters of recommendation from the Guggenheim Foundation and the Smithsonian, and came to experience what he called “magic”—“people expecting me when I had not met them before.”

And yet, even when they are in a room together, Hare’s subjects are revealed as utterly alone. In Wheeling, West Virginia, a husband and wife sit in separate armchairs, a child on each lap, like a pair of isolated islands adrift in a room crammed with doilies, plastic flowers, a collection of lanterns, and cheap art. The husband and wife wear television expressions, slack-jawed and stunned.

“I’ve also discovered that by evening most of masculine Interior America is a little bit drunk,” Hare wrote.

In his writings, Hare acknowledges the “deception” of using a wide-angle lens. Some subjects were not even aware they would appear in the frame, and definitely not imagining that certain details would creep into the picture: electric cords, dirty surfaces, windows and doors that opened onto other, dingier spaces. Sometimes Hare’s camera is pitched to such a capacious angle that the apparent vastness of the room is terrifying. In other pictures, the camera’s position lends itself to claustrophobic effect: floors recede into walls or wallpaper seems to swallow the carpet whole.

If there is a literary analogue, Hare’s photographs might be a short story by Raymond Carver or Lucia Berlin. Hare discovers his decisive moment in the things no one wants him to see. “If anyone tries to keep me from looking somewhere, say, an upstairs bedroom,” he wrote, “that’s where I know I need to go.” There might be an infant alone in a room. Or a man stalking through a boardinghouse, glaring at the camera. “You sonofabitch,” he said to Hare. A telephone cord unwinds across the length of a living room, corralling the various family members. Janet Malcolm observed

Hare enters the homes that Robert Frank sped past when taking the pictures for The Americans.

that with Interior America, Hare enters the homes that Frank sped past when taking the pictures for The Americans.

The spiritless worlds he discovered within reflected his own life. Hare is descended from his paternal steelworker grandfather and a maternal grandfather who worked for the Shredded Wheat factory in Niagara Falls, New York. His mother, chronically depressed, spent days locked in her room. His father was an engineer who took pride in having an employee who washed his car for him. Hare’s life proceeded in seemingly inevitable fashion: He went to engineering school at Columbia University without thinking much about it. He married his first wife, an Austrian waitress named Gertrude, without bothering to fall in love.

He got his first job at Standard Oil (which became Chevron) in California without much trouble. A good recruiter, he noted in Protest Photographs, would have been suspicious of a company man who studied short stories at night.

At Chevron, Hare once worked with a team whose response to the nitrogen dioxide emanating from the refinery stacks was to recommend a way to render the gas colorless so that it would go undetected. Years in, his own invisible fears and unhappiness manifested in chronic nausea and vomiting. When he began photographing in the ’60s, the symptoms disappeared. In 1969, Hare was granted leave from his job to travel the country in an Econoline van and photograph with his Guggenheim money.

With subsequent Guggenheim grants, Hare earned permission to bring his camera into his own workplace, as well as into interiors of other corporations. “He took on the hardest subject there was,”

If the Bancroft Library didn’t agree to Hare’s conditions, Chauncey Hare’s entire photographic record was destined for a bonfire.

recalls Bill Owens, who was then making the pictures that would become Suburbia (1973). “Ordinary people doing ordinary work in ordinary offices.”

Hare’s fight to publish This Was Corporate America in 1984 triggered a period that he describes as cutting ties with the photography and art world. “Each photograph had become a record of promise I had taken on,” he wrote, and to sell those records, or to show them as purely aesthetic images, he believed, would have been tantamount to selling the people.

Ken Light, who was making photographs of industrial workers when he first met Hare in the early 1980s, corresponded with him for years. “He felt a complete responsibility to the people he photographed, and wanting to change the world or change their status and I think that’s why he gave it up,” Light said recently. “With Interior America, people thought he was the new Walker Evans. But Evans was very disconnected from the people he photographed. He was interested in the image, the actual object. And Chauncey was this wonderful photographer for whom the photograph wasn’t enough. He cared about the people.”

After divorcing Gertrude, and giving up custody of their son, Victor, Hare eventually moved in with Orville and Helen, caring for them until Orville’s death. He immersed himself in the life of one of the prostitutes he photographed, and tried to help her beat a heroin addiction. He began attending what he described as “meet-members-of-the-opposite-sex” parties on Saturday nights and “newspaper dating.” Mostly he went out with psychotherapists and psychologists; he baked them apple pies. When Judy Wyatt, a therapist, answered a personal ad in the San Francisco Bay Guardian, she found herself meeting a “wiry man, compact, handsome in a falcon-like way, wearing light-blue corduroy bell-bottoms and a

jacket. There was a tense, imploded energy running stiff through him—a little frightening.” And yet, there was an instant spark between them. The next day, Hare called Wyatt and told her,

“You are the one.” “Our values were a perfect match,” he later wrote. They fell in love, and into lifelong collaboration.

After they were married, Hare got a series of degrees—an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, and an MA in organizational development from Pepperdine University, completing his thesis on employee morale at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, where he was then working. Several months into the job, an EPA worker who had been hired at the same time as Hare leapt from a nearby building to his death. Hare was eventually fired when the agency got wind of his morale survey. During one of their vacations to Yosemite, Wyatt coined the term “work abuse,” and she and Hare, who became a licensed therapist himself, began dedicating their professional lives to counseling people traumatized by their jobs. They published a book, Work Abuse: How to Recognize and Survive It (1997), and they maintain a private practice in San Francisco, where they still live.

One day in 1999, Jack von Euw picked up his phone and heard at the other end of the line the man he’d seen picketing his own art exhibition twenty years before. “It was as if I had received a ransom call,” von Euw wrote. Hare was looking to donate his photographs, but on very specific terms. The work could not be sold; the work could not leave the library; the work could not be shown out of context—hence the statement that accompanies the photographs published in this issue. If the Bancroft Library didn’t agree to Hare’s conditions, well, von Euw was certain that Chauncey Hare’s entire photographic record was destined for a bonfire. He agreed to meet Hare at a warehouse in Oakland with a flashlight, old clothes, and a large screwdriver. What he found was astounding: a massive

collection of prints, negatives, books, accumulations of everything that represented Hare’s life as a photographer. “In my view his work is unparalleled,” von Euw recounted. “You’d have to go back to the days of the Farm Security Administration. Chauncey is a writer, but he writes with his camera. I can’t think of another photographer who is as closely related to writing as he is except maybe Eugene Smith. And his photographs have never been more relevant than they are now.”

Hare was able to get up close to the riders on their BART commutes, he once said, simply because he was fueled by rage, an emotion that, along with severe anxiety, is what continually motivated his work. The aim was always something that lay beyond the offices and kitchens of the lives he encountered:

“My photographs,” he wrote, “demand a spiritual awakening.”

Rebecca Bengal is a writer based in New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

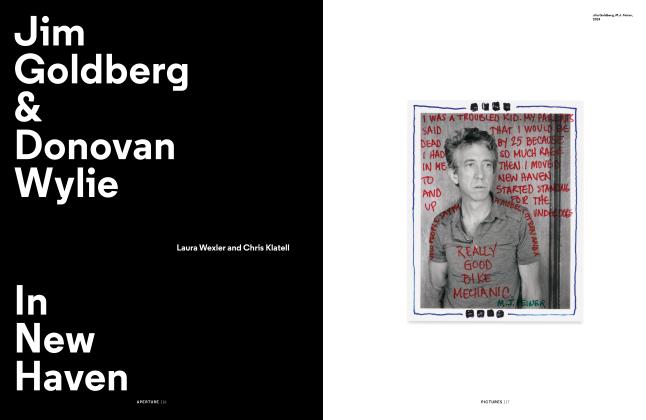

PicturesJim Goldberg & Donovan Wylie: In New Haven

Spring 2017 By Laura Wexler, Chris Klatell -

Words

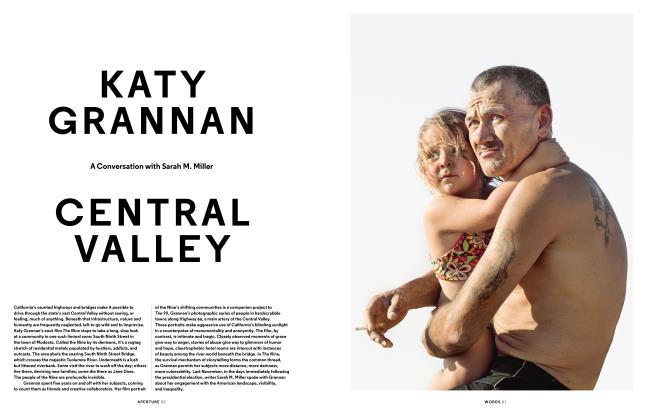

WordsKaty Grannan: Central Valley

Spring 2017 By Sarah M. Miller -

Pictures

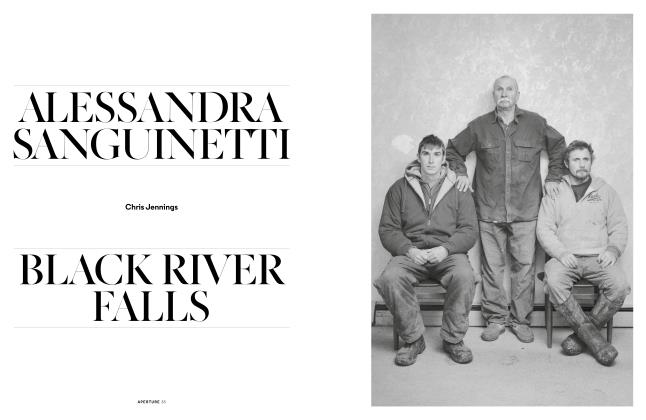

PicturesAlessandra Sanguinetti: Black River Falls

Spring 2017 By Chris Jennings -

Pictures

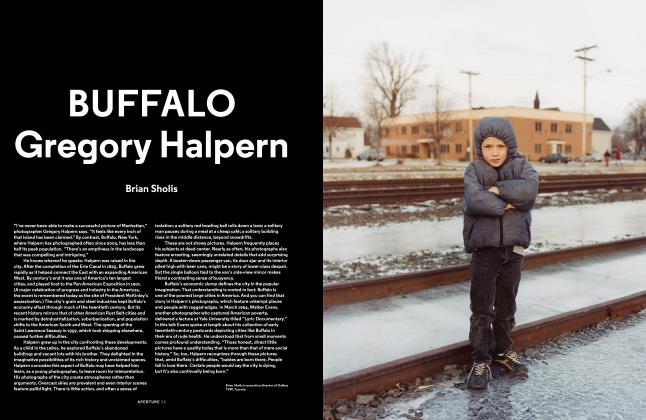

PicturesBuffalo Gregory Halpern

Spring 2017 By Brian Sholis -

Words

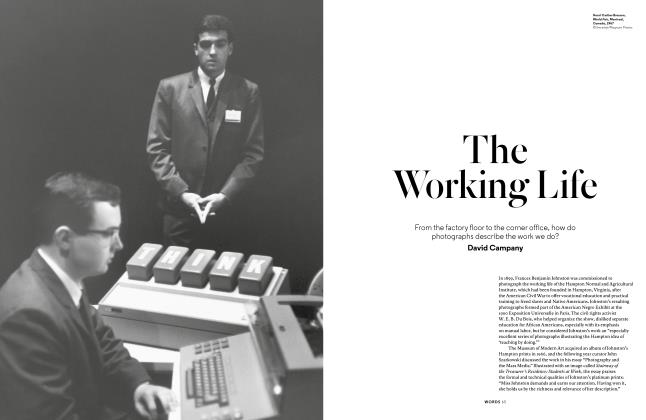

WordsThe Working Life

Spring 2017 By David Campany -

Words

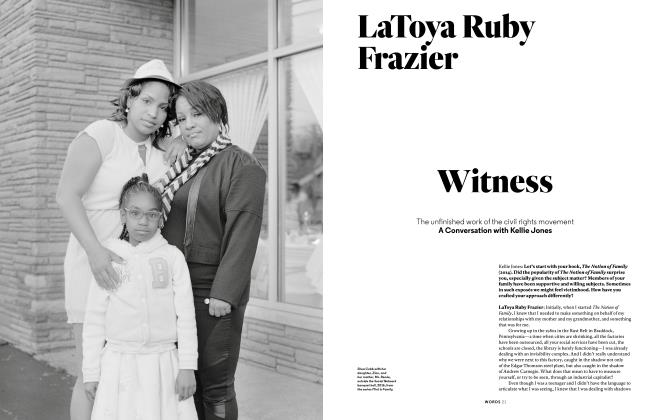

WordsLatoya Ruby Frazier: Witness

Spring 2017 By Kellie Jones

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Rebecca Bengal

-

Spotlight

SpotlightNatalie Krick

Winter 2017 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

WordsDiana Markosian Santa Barbara

Winter 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

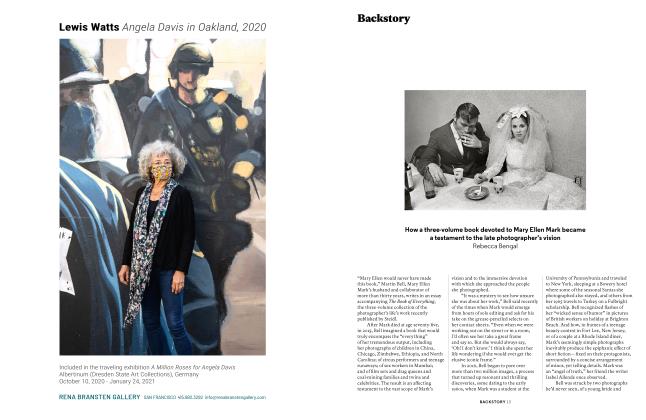

Backstory

Winter 2020 By Rebecca Bengal -

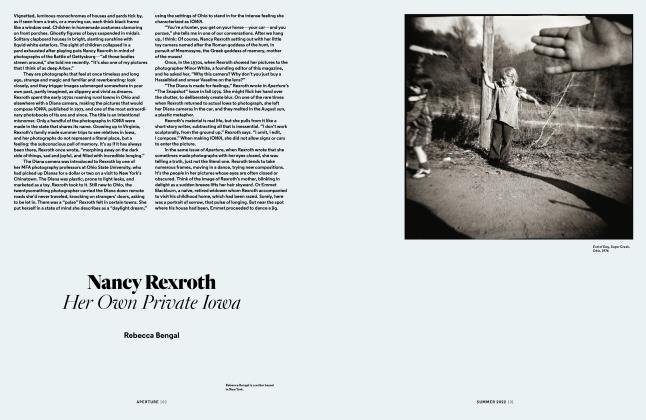

Nancy Rexroth

SUMMER 2022 By Rebecca Bengal -

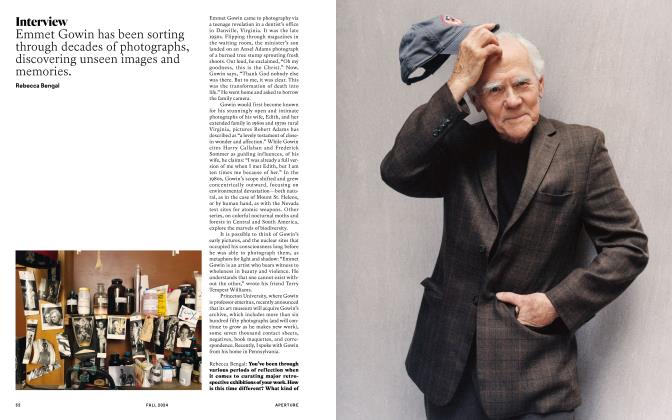

Interview

FALL 2024 By Rebecca Bengal -

Reviews

SPRING 2025 By Samuel Medina, Noa Lin, Zack Hatfield, 2 more ...

Words

-

Words

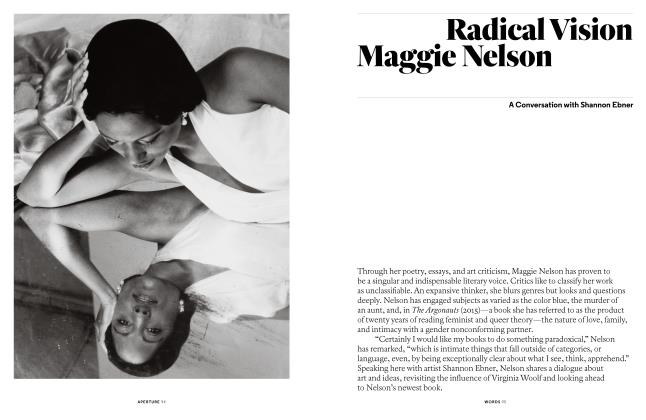

WordsRadical Vision Maggie Nelson

Summer 2019 -

Words

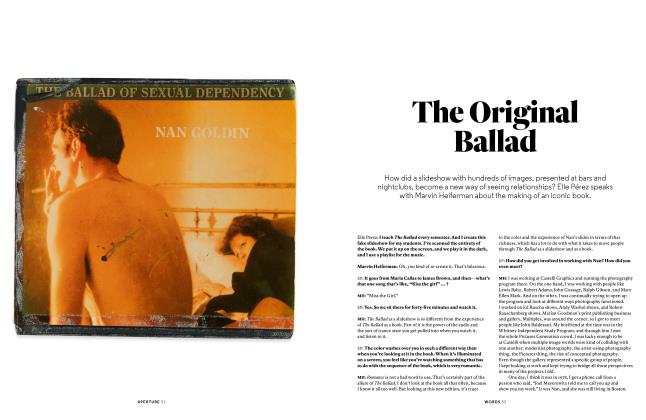

WordsThe Original Ballad

Summer 2020 -

Words

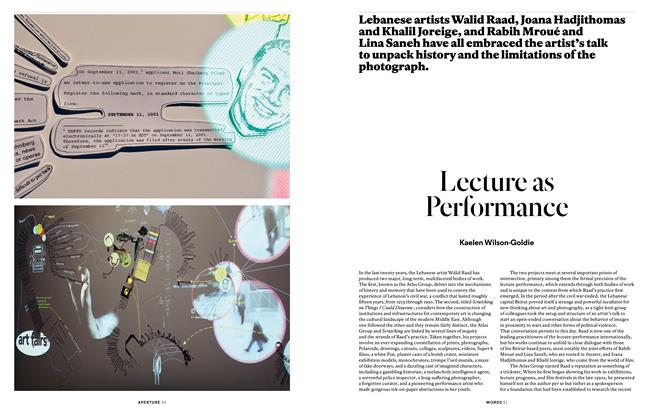

WordsLecture As Performance

Winter 2015 By Kaelen Wilson-Goldie -

Words

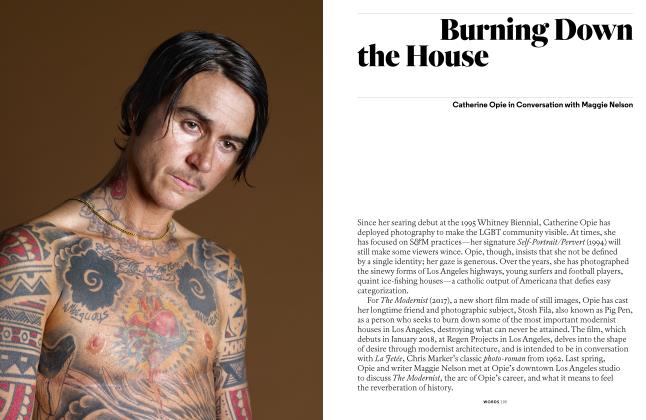

WordsBurning Down The House

Winter 2017 By Maggie Nelson -

Essay

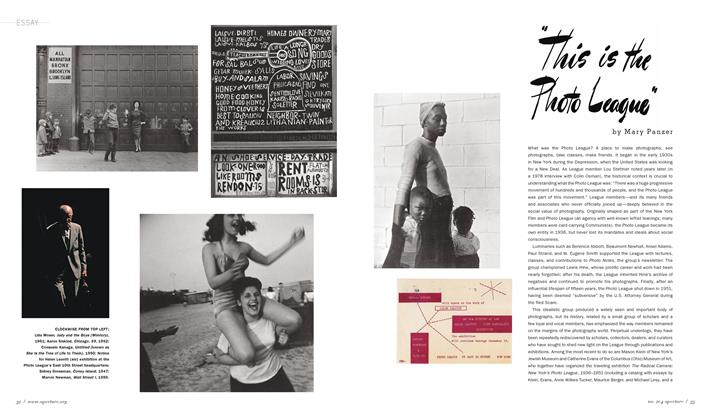

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Words

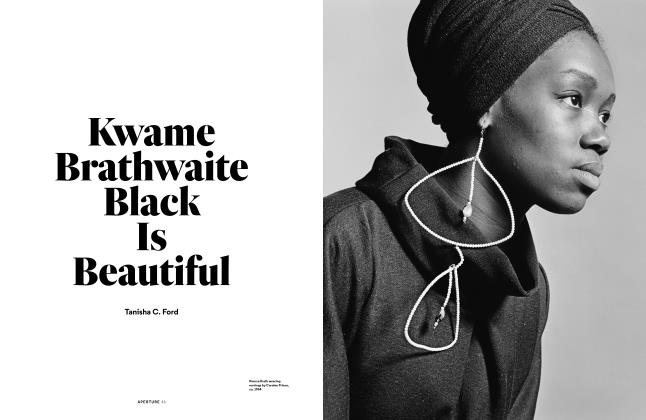

WordsKwame Brathwaite: Black Is Beautiful

Fall 2017 By Tanisha C. Ford