Pictures

Len Lye Shadowgraphs

Filmmaker and sculptor Len Lye made about forty-eight cameraless photographic portraits of friends and acquaintances.

Winter 2013 Geoffrey BatchenLen Lye Shadowgraphs

Geoffrey Batchen

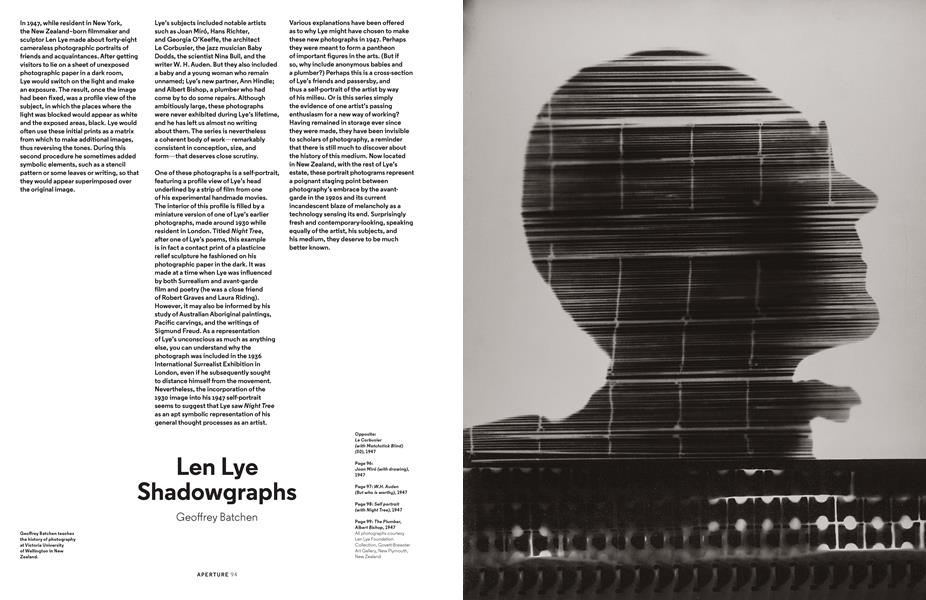

In 1947, while resident in New York, the New Zealand-born filmmaker and sculptor Len Lye made about forty-eight cameraless photographic portraits of friends and acquaintances. After getting visitors to lie on a sheet of unexposed photographic paper in a dark room, Lye would switch on the light and make an exposure. The result, once the image had been fixed, was a profile view of the subject, in which the places where the light was blocked would appear as white and the exposed areas, black. Lye would often use these initial prints as a matrix from which to make additional images, thus reversing the tones. During this second procedure he sometimes added symbolic elements, such as a stencil pattern or some leaves or writing, so that they would appear superimposed over the original image.

Lye’s subjects included notable artists such as Joan Miró, Hans Richter, and Georgia O’Keeffe, the architect Le Corbusier, the jazz musician Baby Dodds, the scientist Nina Bull, and the writer W. H. Auden. But they also included a baby and a young woman who remain unnamed; Lye’s new partner, Ann Hindle; and Albert Bishop, a plumber who had come by to do some repairs. Although ambitiously large, these photographs were never exhibited during Lye’s lifetime, and he has left us almost no writing about them. The series is nevertheless a coherent body of work—remarkably consistent in conception, size, and form—that deserves close scrutiny.

One of these photographs is a self-portrait, featuring a profile view of Lye’s head underlined by a strip of film from one of his experimental handmade movies. The interior of this profile is filled by a miniature version of one of Lye’s earlier photographs, made around 1930 while resident in London. Titled Night Tree, after one of Lye’s poems, this example is in fact a contact print of a plasticine relief sculpture he fashioned on his photographic paper in the dark. It was made at a time when Lye was influenced by both Surrealism and avant-garde film and poetry (he was a close friend of Robert Graves and Laura Riding). However, it may also be informed by his study of Australian Aboriginal paintings, Pacific carvings, and the writings of Sigmund Freud. As a representation of Lye’s unconscious as much as anything else, you can understand why the photograph was included in the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, even if he subsequently sought to distance himself from the movement. Nevertheless, the incorporation of the 1930 image into his 1947 self-portrait seems to suggest that Lye saw Night Tree as an apt symbolic representation of his general thought processes as an artist.

Various explanations have been offered as to why Lye might have chosen to make these new photographs in 1947. Perhaps they were meant to form a pantheon of important figures in the arts. (But if so, why include anonymous babies and a plumber?) Perhaps this is a cross-section of Lye’s friends and passersby, and thus a self-portrait of the artist by way of his milieu. Or is this series simply the evidence of one artist’s passing enthusiasm for a new way of working? Having remained in storage ever since they were made, they have been invisible to scholars of photography, a reminder that there is still much to discover about the history of this medium. Now located in New Zealand, with the rest of Lye’s estate, these portrait photograms represent a poignant staging point between photography’s embrace by the avantgarde in the 1920s and its current incandescent blaze of melancholy as a technology sensing its end. Surprisingly fresh and contemporary-looking, speaking equally of the artist, his subjects, and his medium, they deserve to be much better known.

Geoffrey Batchen teaches the history of photography at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesPaul Trevor

Winter 2013 By Chris Boot -

Pictures

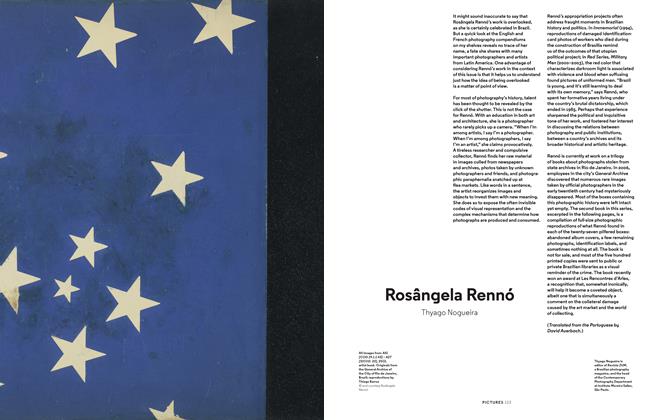

PicturesRosângela Rennó

Winter 2013 By Thyago Nogueira -

Pictures

PicturesMarianne Wex

Winter 2013 By David Campany -

Pictures

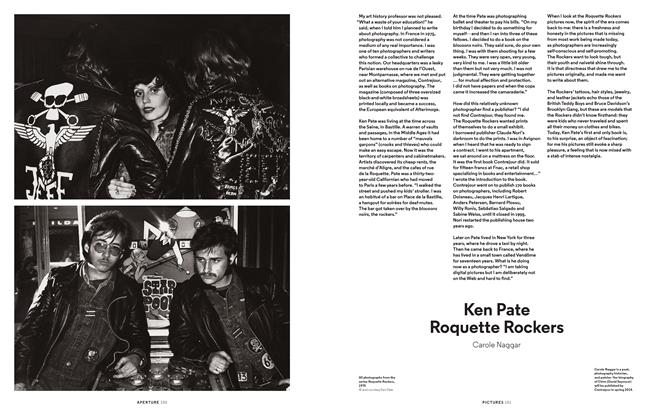

PicturesKen Pate Roquette Rockers

Winter 2013 By Carole Naggar -

Pictures

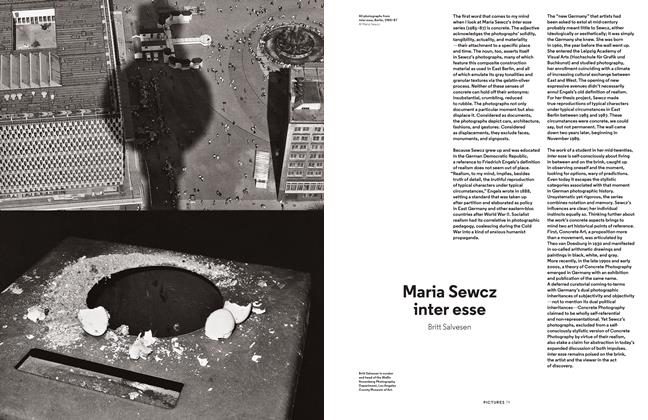

PicturesMaria Sewcz Inter Esse

Winter 2013 By Britt Salvesen -

Pictures

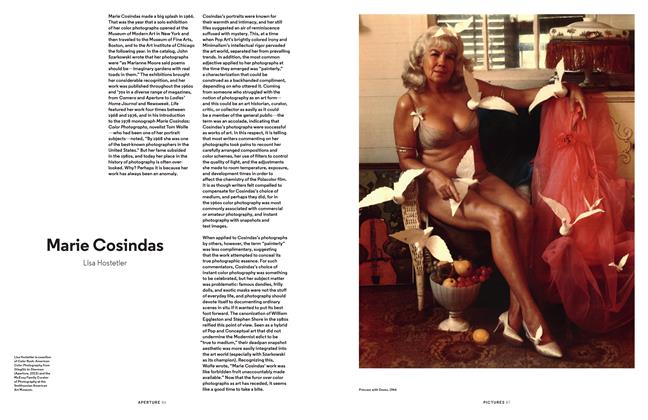

PicturesMarie Cosindas

Winter 2013 By Lisa Hostetler

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Geoffrey Batchen

-

Pictures

PicturesNoisy Pictures

Fall 2016 -

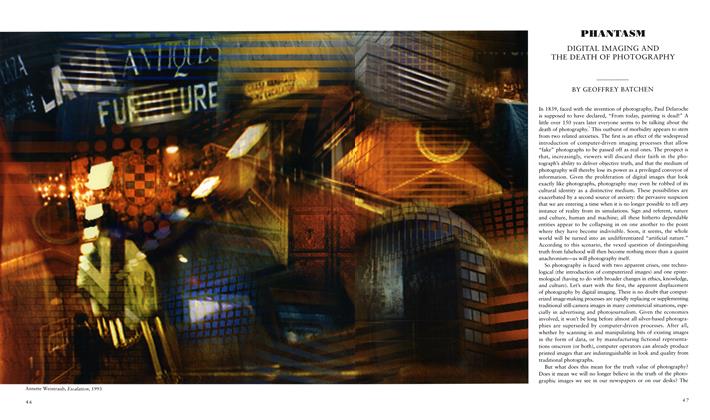

Phantasm

Summer 1994 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Book Excerpts

Book ExcerptsGeoffrey Batchen: Forget Me Not: Photography & Remembrance

Winter 2004 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Books

BooksTaryn Simon: An American Index Of The Hidden And Unfamiliar

Winter 2007 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Pictures Generation

Spring 2010 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Words

WordsObserving By Watching: Joachim Schmid And The Art Of Exchange

Spring 2013 By Geoffrey Batchen