TREVOR PAGLEN

The twenty-first century has already become a photographic century, even more than the nineteenth or the twentieth centuries. Despite the emergence of new regimes of photography and debates about the politics of imaging, photographers, ironically, have had remarkably little to say about how new forms of imaging shape our political and cultural lives.

The most obvious changes have come from advancements in digital cameras, coupled with new ways to search and share “cloud-based” images. Flickr, Facebook, and Google image search have remarkably transformed how we see the world in general and photographs in particular. With a quick search on my laptop or phone, I can browse billions of images and instantly access photographs from my friends’ Facebook pages, combat soldiers’ photographs from Afghanistan and Iraq, and tourist snapshots from Machu Picchu and the Bahamas. Moreover, I can search the metadata of those photographs and see who took them, when and where, on what kind of cameras, and at what aperture and shutter speed. Less obvious is the fact that those cloud-based photo-networks and search capabilities are just the public—or corporate—version of a much broader photographic revolution. Imaging systems—i.e. photography—in the service of state power are far more advanced and wide-reaching than anything I can do on my laptop or cell phone.

9/11 provided the popular justification for new forms of state photography and for the increasing role of the image in social control, now surpassing anything George Orwell imagined. In downtown New York, police cars are equipped with automated cameras tasked to record every license plate they pass, identifying any car whose driver might have a suspended license or overdue registration. This information is then held in searchable archives detailing where each car was on a given date. Next-generation airport security cameras in Florida instantly “recognize” the identity of anyone traversing their fields of view. And that’s just the local cops and airports.

(continued on page 68)

(Paglen continued)

CIA and military drones—little more than cameras and missiles mounted to remotecontrol aircraft—flown by pilots in Nevada, produce new relational geographies of war while reorienting our cultural relationships and attitudes toward warfare. When an American robot assassinates someone in Yemen, is there anyone “over here” to hear the scream? Needless to say, the National Security Agency’s once-illegal warrantless domestic surveillance program (retroactively “legalized” with Barack Obama’s support) almost certainly correlates data from email and cell-phone records with digital images and photographs, search terms, bank-account statements, and other electronic records and traces.

A final, perhaps not-too-obvious point: these “new” forms of photography are relational. Flickr, for example, is a site for presenting photography, but it’s also a network. That’s the point. Ditto for the Predator aircraft; the drone is a camera, but it’s also a relational geographyspatial, political, and cultural, with remotecontrolled missiles. The drone’s remote, realtime imaging system enables the creation of a non-contiguous “space” of warfare, composed of pilots, intelligence analysts, weapons officers, battlefield commanders, and soldiers “on the ground,” all of whom participate in a given mission despite the fact that they’re scattered across the earth. The same is true of the facial-recognition camera, coming soon to your local airport. Photography has become a relational medium—a meta-network of machines, politics, culture, and ways of collective seeing.

Photography is not going away. On the contrary, it’s just getting going. Photography is becoming more and more inseparable from the workings of state power, corporate interests, and our everyday lives. And this is something I think photographers should critically reflect upon. ■

Artist Trevor Paglen’s latest book, Invisible, was published by Aperture in 2010.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueTalking Pictures

Fall 2011 By John Pilson -

Essay

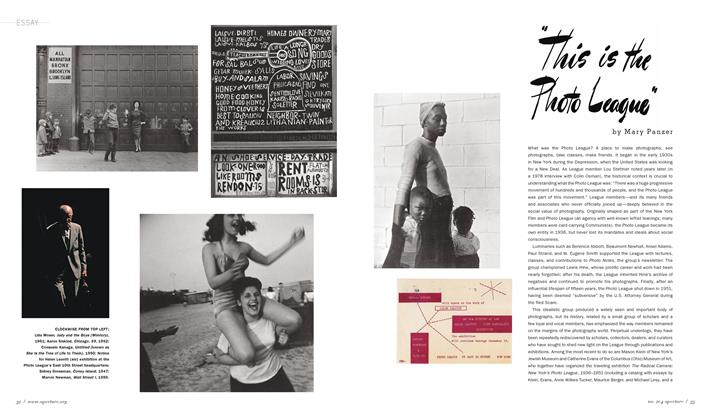

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAn Atlas Of Decay: Cyprien Gaillard

Fall 2011 By Brian Dillon -

On Location

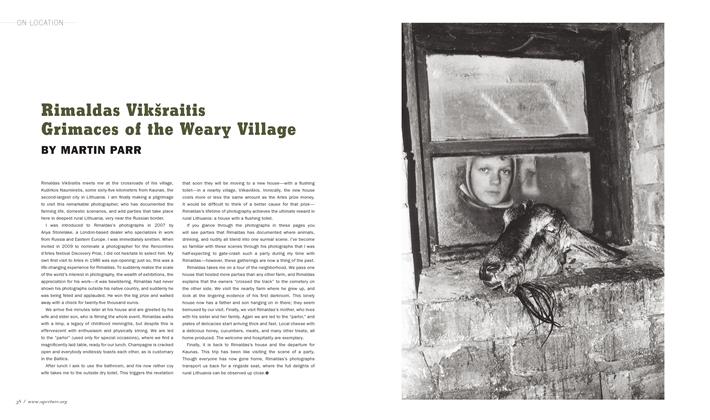

On LocationRimaldas Vikšraitis: Grimaces Of The Weary Village

Fall 2011 By Martin Parr -

Portfolio

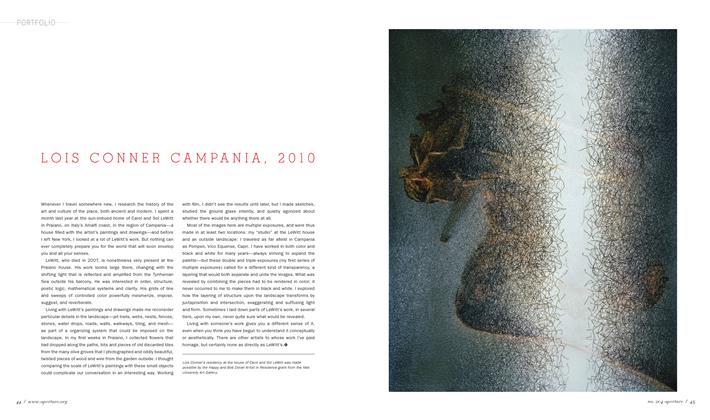

PortfolioLois Conner: Campania, 2010

Fall 2011 By Lois Conner -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau

Fall 2011 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Trevor Paglen

The Anxiety Of Images

-

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesMark Sealy To Help Me Understand This

Fall 2011 -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau

Fall 2011 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAtom Egoyan

Fall 2011 By Atom Egoyan -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesDeborah Willis

Fall 2011 By Deborah Willis -

The Anxiety Of Images

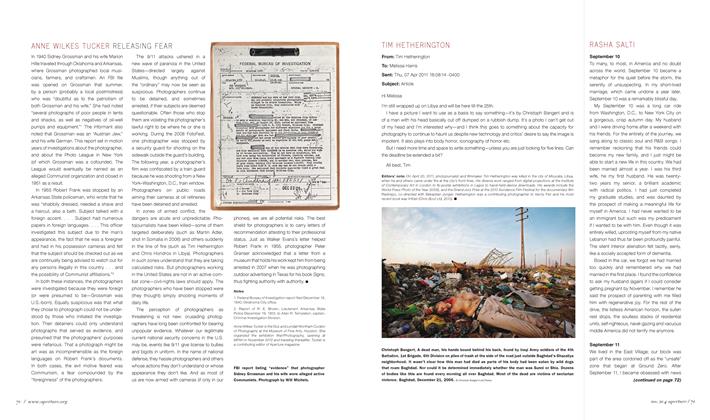

The Anxiety Of ImagesThomas Keenan

Fall 2011 By Özge Ersoy, Thomas Keenan -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesTim Hetherington

Fall 2011 By Tim Hetherington