THOMAS KEENAN

Özge Ersoy

The “photo-opportunity” refers to the moment when something happens in the world in order that a picture can be taken of it. The traditional epistemology of photography presumes that first of all there’s something in the world, and then, in an independent or neutral way, it’s represented somewhere else. The structure of the photo-opportunity, however, indicates that at least sometimes things appear in the world for the sake of a picture, that they wouldn’t happen without the image, and that the possibility of representation precedes and in some sense makes the event. The sequence doesn’t get completely destroyed, but rather somehow scrambled, so that things happen in front of cameras that are waiting for them to happen.

The slogan of this might be a phrase from a 1995 New York Times story from Sarajevo, in which the reporter chronicled a sniper shooting captured on videotape. The reason it was captured on videotape is, the reporter says, that “there was a cameraman there, waiting.” This phenomenon of a “cameraman there, waiting” doesn’t seem to be singular anymore; it is a feature of contemporary reality. Cameras create a space and time of appearance in which things happen.

It may be that this is a structure of representation or signification itself, and cameras are simply the currently privileged medium for that. But the period we’re talking about begins with the turn of the 1990s—with the 1989 overthrow of Ceausescu in Romania, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the first Gulf War, and the Rodney King tape, among other things. The Gulf War was the first time reporters were systematically embedded with fighting forces. It was also famous, or infamous, for the initial experiments in corralling journalists in briefing rooms and hotels, and subjecting them to videotapes that were made by weapon systems as a substitute for reporting. This was another kind of photoopportunity—the mechanically or technically generated news image from laser-guided bombs, tele-guided missiles, and the like.

Reporting from within military commands was virtually the only way that foreign journalists could cover the first Gulf War, on both sides. A few went “unilateral” as they called it; they operated outside of the control of military forces. These reporters were mostly in Iraq—some were captured and some were killed. The bulk of the world’s media, however, was in Saudi Arabia with the Americans and their coalition. Reporters have always traveled close to militaries, of course; but the Gulf War constituted the birth of an official practice and doctrine of embedded reporting.

In his 1992 book Hotel Warriors: Covering the Gulf War, John Fialka quotes a Marine officer: “We regarded [journalists] as an environmental feature of the battlefield, kind of like the rain,” he says. “If it rains, you operate wet.” The media are equivalent to a force of nature. You can protect yourself against some of the negative impacts but you can’t do anything about its existence. You simply factor it into your negotiations with all the other givens, and try to make use of it. Media are a constitutive feature of battlefield reality. I use “media” in the broad sense, to include traditional newsgathering with reporters and cameras, as well as the cameras carried by fighters and fighting machines, on all sides, and then also people who are independently or critically monitoring the activities of states or militaries (we could nickname them “NGOs,” and they are thoroughly mediatized as well). My interest is in the reality-constitutive effects of media practices.

Traditional journalism is still powerful at the level of practices, assumptions, and expectations. But there are all sorts of practices that challenge, extend, undermine, and transform it. There are other ways of doing it, and there always have been, but they have been buried beneath the hegemonic institution of photojournalism and the heroic figure of the photojournalist. I am interested in trying to identify and display what I call a “double gesture”: a self-critical hesitation, a turning away and a refocusing, an investigation of the event of photography itself. It explores the time and space in which reality anticipates the camera, where the image constitutes the event—and it does it with cameras.

There’s a tradition of thinking about critique as something that comes from outside. According to this traditional epistemology, one should be at a distance from the object in order to criticize it. In all sorts of contexts, we value this critical distance. But there’s something flawed about the idea, in ethical terms as well as epistemological. A critique—or maybe we ought to call it a “deconstruction”—of an object or an institution needs to remain attached to it, invested in it, contaminated by it. One only critiques something that one deems worthy of critiquing. This engagement implies, then, an affirmation of some possibility in the object, event, or practice that is being criticized. Every critique therefore commits itself to concretizing, realizing, or manifesting what those other possibilities might be. Jacques Derrida uses the term “institution” for this. The deconstruction of an institution implies taking a position and making a commitment to an alternative institution. In short, if a thing is worth critiquing, one must take the risk of building the alternative that’s implied by the critique.

Documentary and photojournalism are both rhetorical practices. Literary critic Paul de Man distinguished between two moments of rhetoric. The first concerns ways of knowing. If I say to you: “She’s as lovely as a flower,” I’m not simply praising her but I’m offering you some knowledge—you know what a flower is, and now you know that she is like a flower. This is the traditional cognitive function of rhetoric. The other dimension is persuasive, which is about producing effects. I speak not to teach you something but to get you to do something: vote, buy, go to war, love, whatever. There is a meaningful distinction between these two, but they are also linked. There are images that convey what you call “immediacy”; they capture a moment, make it known and knowable, and send it somewhere else. But they are not bound by that demand. On the one hand, the distinction between documentary and photojournalism gets productively collapsed or fuzzy. On the other hand, we’re not entirely in control of that distinction anymore, which means that the phenomenon of unleashing becomes possible.■

Thomas Keenan teaches literature and directs the Human Rights Project at Bard College. With Carles Guerra, he curated the 2010 traveling exhibition Antiphotojournalism. Keenan is a contributing editor of Aperture magazine.

Keenan’s interview with Özge Ersoy was originally published online at ArtTerritories.net.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueTalking Pictures

Fall 2011 By John Pilson -

Essay

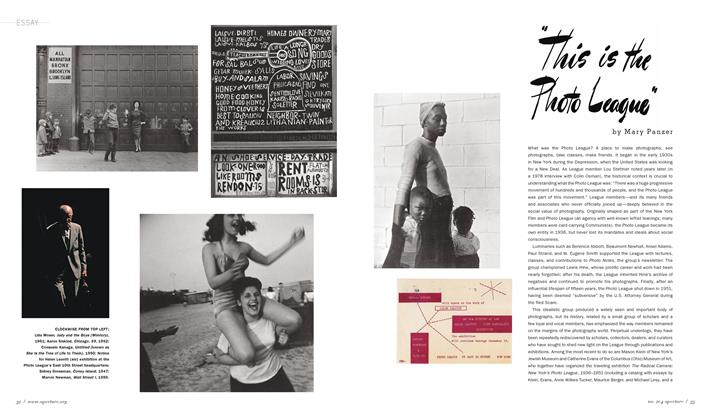

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAn Atlas Of Decay: Cyprien Gaillard

Fall 2011 By Brian Dillon -

On Location

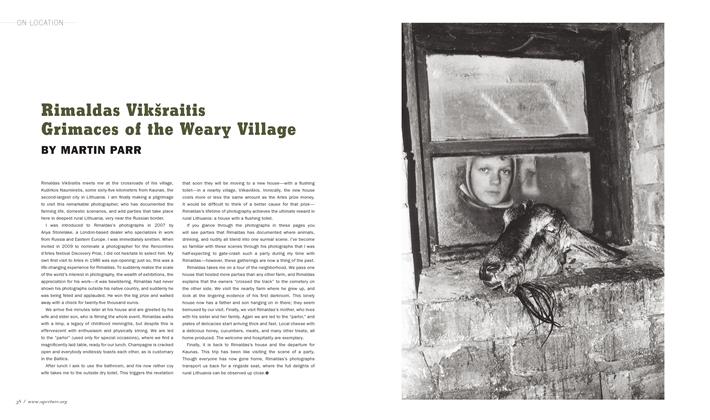

On LocationRimaldas Vikšraitis: Grimaces Of The Weary Village

Fall 2011 By Martin Parr -

Portfolio

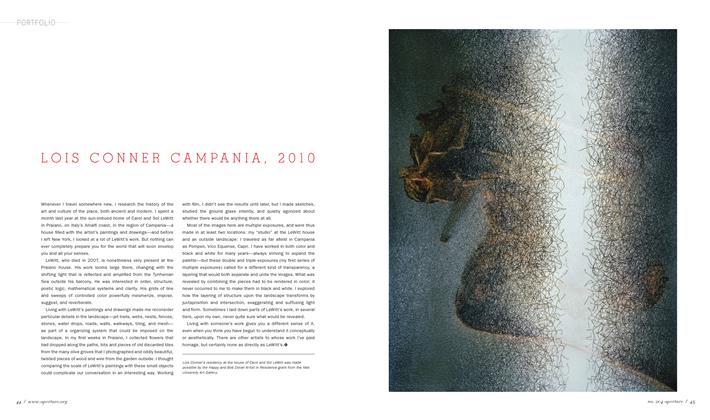

PortfolioLois Conner: Campania, 2010

Fall 2011 By Lois Conner -

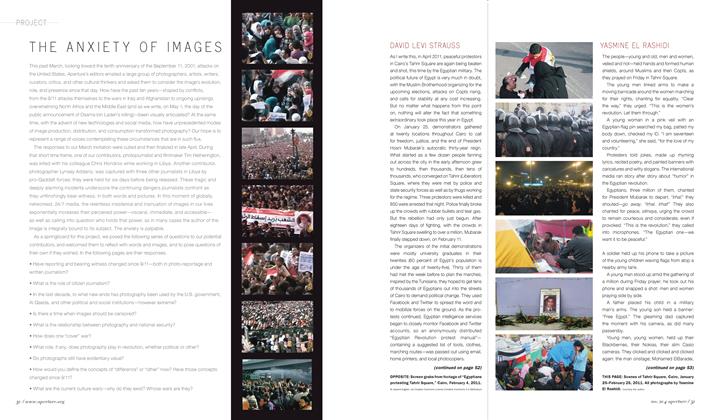

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau

Fall 2011 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Thomas Keenan

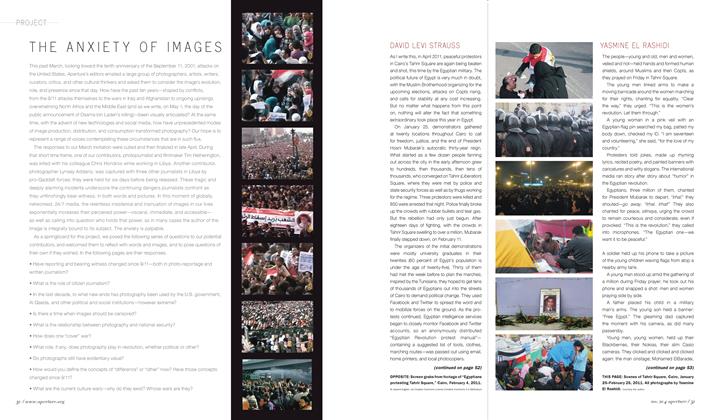

The Anxiety Of Images

-

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesMark Sealy To Help Me Understand This

Fall 2011 -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAriella Azoulay: The Architecture Of Execution

Fall 2011 By Ariella Azoulay -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesDavid Levi Strauss

Fall 2011 By David Levi Strauss -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesJulian Stallabrass

Fall 2011 By Julian Stallabrass -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesTim Hetherington

Fall 2011 By Tim Hetherington -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesYasmine El Rashidi

Fall 2011 By Yasmine El Rashidi