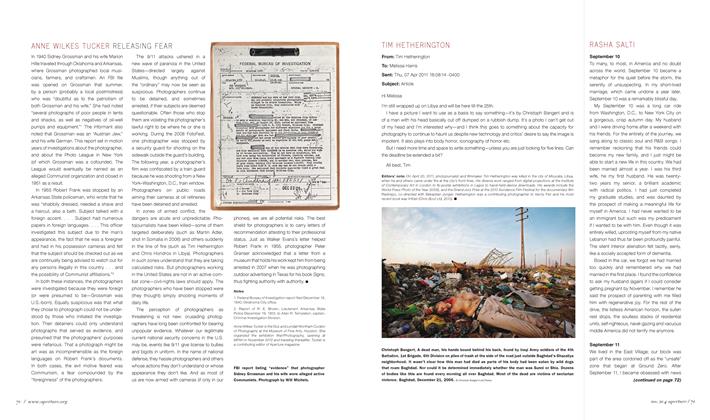

RASHA SALTI

September 10

To many, to most, in America and no doubt across the world, September 10 became a metaphor for the quiet before the storm, the serenity of unsuspecting. In my short-lived marriage, which came undone a year later, September 10 was a remarkably blissful day.

My September 10 was a long car ride from Washington, D.C., to New York City on a gorgeous, crisp autumn day. My husband and I were driving home after a weekend with his friends. For the entirety of the journey, we sang along to classic soul and R&B songs. I remember reckoning that his friends could become my new family, and I just might be able to start a new life in this country. We had been married almost a year. I was his third wife, he my first husband. He was twentytwo years my senior, a brilliant academic with radical politics. I had just completed my graduate studies, and was daunted by the prospect of making a meaningful life for myself in America. I had never wanted to be an immigrant but such was my predicament if I wanted to be with him. Even though it was entirely willed, uprooting myself from my native Lebanon had thus far been profoundly painful. The silent interior alienation felt tacitly, eerily, like a socially accepted form of dementia.

Boxed in the car, we forgot we had married too quickly and remembered why we had married in the first place. I found the confidence to ask my husband (again) if I could consider getting pregnant by November. I remember he said the prospect of parenting with me filled him with regenerative joy. For the rest of the drive, the listless American horizon, the sullen rest stops, the soulless stacks of residential units, self-righteous, navel-gazing and vacuous middle America did not terrify me anymore.

September 11

We lived in the East Village; our block was part of the area cordoned off as the “unsafe” zone that began at Ground Zero. After September 11,1 became obsessed with news and analysis—as a lot of people did. Every day, I collected Arabic-language newspapers from a shop on 14th Street. It took me a month or so to realize how I cautiously packed them in my bag to hide them, that I no longer spoke Arabic when making calls from public phones.

(continued on page 72)

(Salti continued)

Shortly after Thanksgiving, I met with a Lebanese friend for a cup of coffee. We traded anecdotes about the INS—it turned out we had both submitted applications for a green card in the days preceding September 11. From laughing at our petty miseries, we turned for the first time to our experiences on that day and what ensued in New York—as Arabs, as Muslims. I found myself describing feelings and states of mind I had not articulated even to myself. And I realized I was speaking in Arabic, in a public place. It came naturally, the Arabic—and it felt like a relief. In spite of the protections afforded by privilege—class and other—I had interiorized so much fear. I was stunned.

September 12

The eleventh Istanbul Biennial opened on September 11, 2009. On September 12 the program hosted a panel discussion called “Who Needs a Worldview?” In his prefatory remarks, writer and theorist Brian Holmes noted the significance of the date, as “the day after” September 11 and its commemorations, and invited speakers to consider that in their discussions. Meltem Ahiska, a renowned Turkish sociologist, reminded Holmes that September 12 was significant in itself for Turkey: it was the date, in 1980, of the military coup that inaugurated a very violent chapter in recent Turkish history, crushing the leftist movement and starting the war against Kurdish communities for years to come.

Part of the danger in writing the “history” of September 11, 2001, and charting a worldview that begins there, is eliding the chronological cartography of days in September that are equally sinister. Perhaps the key to liberating the inhibited mourning of those who lost family and loved ones on that day in the United States starts from a reckoning with the pain of others, years before and years after, across the world. ■

Curator and writer Rasha Salti lives and works in Beirut, Lebanon. She has contributed to The Jerusalem Quarterly Report (Palestine), The London Review of Books, and many other publications. Salti and photographer Ziad Antar collaborated on the exhibition and publication Beirut Bereft, The Architecture of the Forsaken and Map of the Derelict (Sharjah, 2009).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueTalking Pictures

Fall 2011 By John Pilson -

Essay

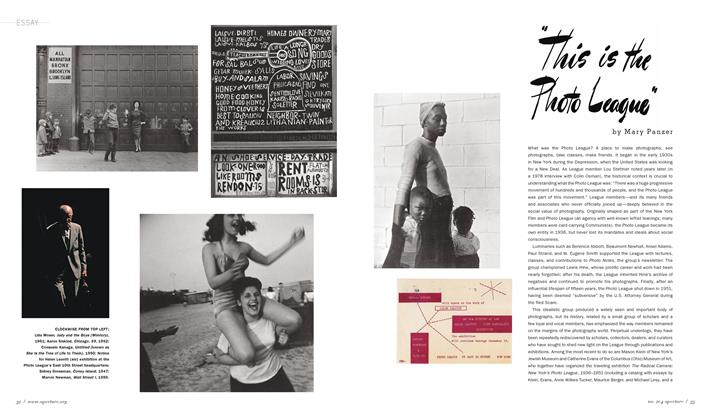

Essay"This Is The Photo League"

Fall 2011 By Mary Panzer -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAn Atlas Of Decay: Cyprien Gaillard

Fall 2011 By Brian Dillon -

On Location

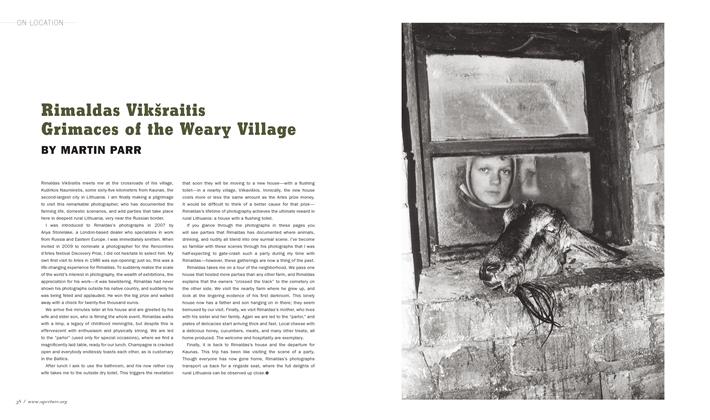

On LocationRimaldas Vikšraitis: Grimaces Of The Weary Village

Fall 2011 By Martin Parr -

Portfolio

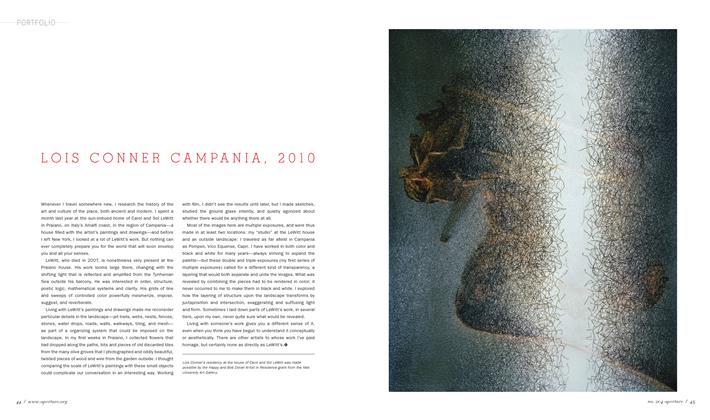

PortfolioLois Conner: Campania, 2010

Fall 2011 By Lois Conner -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau

Fall 2011 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

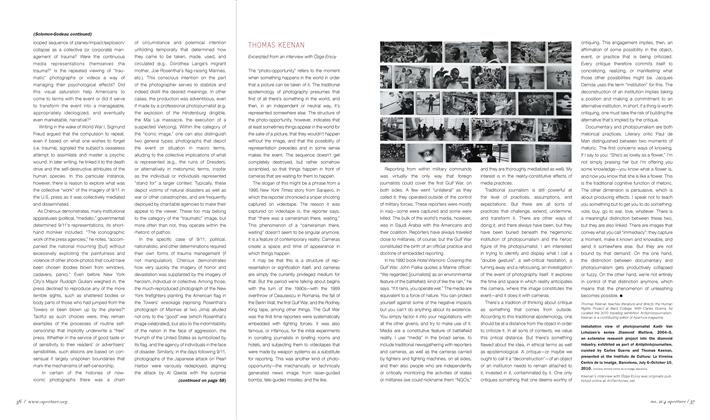

The Anxiety Of Images

-

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesMark Sealy To Help Me Understand This

Fall 2011 -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesAtom Egoyan

Fall 2011 By Atom Egoyan -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesThomas Keenan

Fall 2011 By Özge Ersoy, Thomas Keenan -

The Anxiety Of Images

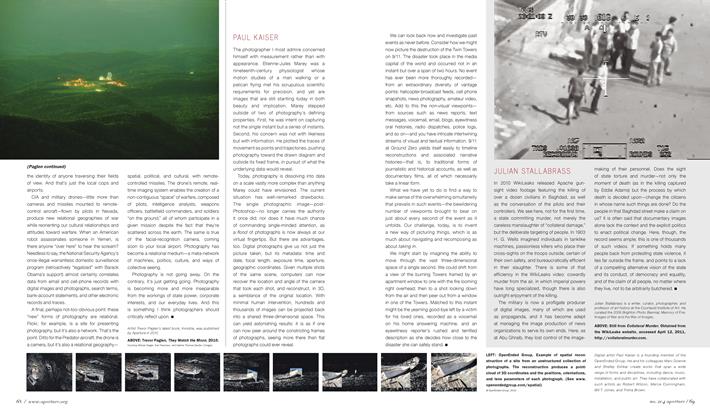

The Anxiety Of ImagesPaul Kaiser

Fall 2011 By Paul Kaiser -

The Anxiety Of Images

The Anxiety Of ImagesTim Hetherington

Fall 2011 By Tim Hetherington -

The Anxiety Of Images

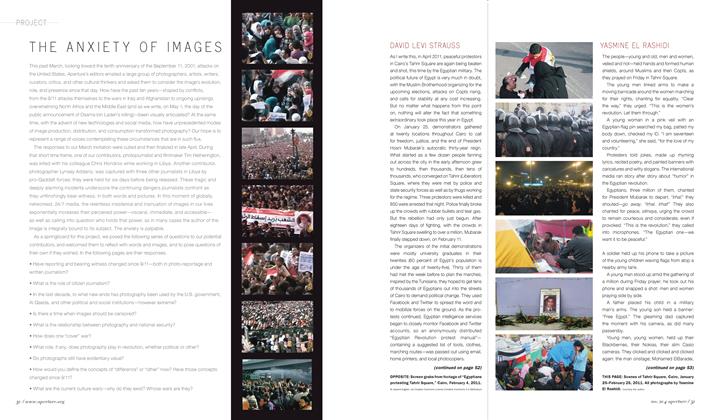

The Anxiety Of ImagesYasmine El Rashidi

Fall 2011 By Yasmine El Rashidi