KHOSHBAKHTI "BLESSED HAPPINESS" IN IRAN

WORK IN PROGRESS

PAOLO WOODS

SERGE MICHEL

In 2002 Iran was famously labeled part of an "axis of evil" by George W. Bush. Among many Americans Iran is often perceived, with reason, as a threatening state ruled by an iron-fisted theocratic Shiite regime, and by a president who, in defiance of the United States and much of the international community, steadfastly asserts Iran's sovereign right to develop its nuclear capabilities. Provoking the ire of many with inflammatory statements—including dismissals of the Holocaust—Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, democratically elected in 200y after running on a populist platform and garnering great support from the country’s lower class, has emerged an outsized villain on the global stage. However, beyond the news of states jockeying for power, advantage, and regional influence (especially now that the future of its onetime enemy Iraq is in play), we hear little of the lives of Iran’s citizens.

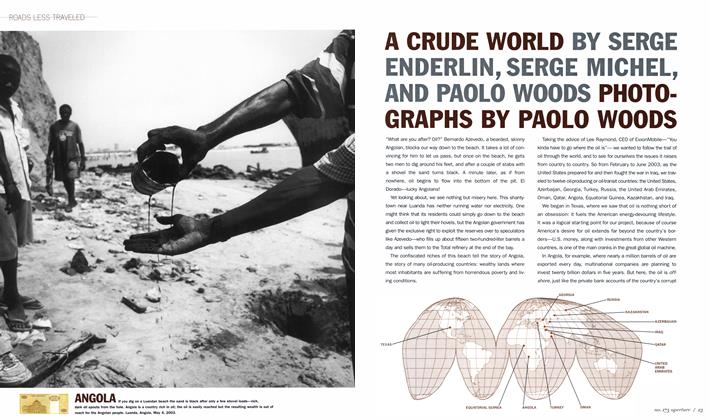

Before deciding to focus on Iran, photographer Paolo Woods and journalist Serge Michel had collaborated on numerous projects—tracking the flow of oil through twelve countries, from Siberia to Angola, from Baku to the United States, as well as chronicling America’s invasions into Afghanistan and Iraq. The two originally met in Iran, and after they had worked so extensively in the region, it was a logical place for this itinerant team to return—the country was now the center of grave international tensions—in an effort to scratch its inscrutable surface.

For Serge Michel, this would be a return to a country he already knew well. Iran’s culture and extensive history had long held sway over his imagination, and in 1998, he moved to Tehran from his home in Switzerland to work as a freelance journalist for Le Figaro in Paris and Le Temps in Geneva. He would remain there for four years, learning some Farsi and discovering a perspective on Iranian mind and society that few Westerners have the opportunity to experience. During his years in Iran, Michel observed a profound awareness of the past that is integral to daily life in the country. He writes:

The history of Iran is a three-thousand-year-old story that makes you want to weep, and contemporary Iranians often referto it. It is a story of a cultured people who are mostly uninterested in fighting and are nearly always in the role of victim. The country’s remarkable achievements, its golden ages, were regularly destroyed by invaders: Arabs in the seventh century, Mongols in the thirteenth century, Afghans in the eighteenth century. More recently, during World War II, the English and the Soviets coolly divided up the Iranian territory, the British benefiting from the southern half, where they exploited Iranian oil. And when Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddeq stood up in 1951 to nationalize oil—a supremely modern act—the CIA fomented a coup d’état. The mullahs themselves are sometimes described by Iranians today as a band of invaders who wanted to wipe out the progress accomplished by the last shah, Mohammed Reza. Conspiracy theories have long proliferated in Tehran, suggesting that the mullahs were sent by an evil Westerner from Britain or the United States to prevent the emergence of a regional power that was finally, because of oil, about to break away from the curse of martyrdom. It is a history of defeat and frustration, and its lessons are deeply ingrained in the Iranian heart.

As an outsider living in Tehran, Michel was of course subject to the same restrictions as the Iranians in terms of day-to-day habits—the strict dress code and rules about public behavior (particularly during the country’s many mourning days and months), observation of the fast during Ramadan, Western films and music available only on the black market, and so on. On a larger level, Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, also responsible for censure, had deemed that the articles Michel was writing—on such volatile subjects as student demonstrations, the murders of dissidents, and the repression of reformist newspapers—were crossing the red line, and they issued him multiple warnings.

Nonetheless, Michel began to sense that, despite the rigid societal structures,

most people lead ordinary, pleasant lives; they have adapted to the system and even manage to take advantage of it. Iran cannot be summed up by the cliché of antiquated ayatollahs crushing a npnnlp whn arp ctj"i icilincf frx.fr.f-.-Q-'.»— * t -I - I— 1 ■ u. . people who are strugling for freedom. Most Iranians have no desire to live through another major political upheaval—and some enjoy the fruits of the country’s new prosperity.

There existed a level of contentment in the country that Michel had not anticipated.

Woods and Michel’s proposition of “ordinary, pleasant lives” in Iran may come as a surprise to many. Those following recent reports about government crackdowns against labor leaders, universities, the press, and women’s rights advocates, among others, and the situation of Iran’s rationed gasoline and runa way inflation might tend to dismiss this concept as ironic, or at least ingenuous. Michel and Woods are clear that their thesis is serious, but shoidd not be viewed as an endorsement of the current regime in power.

Michel and Woods did not use an empirical instrument or poll to try to measure the slippery notion of what they call “happiness” in Iran. Neither did they wish to interview only people whose social position was directly connected with recent good fortune—such as the powerful bazaar -merchants who are cashing in on the new wave of foreign imports, or the Basijis, the feared Islamic law-enforcement volunteers whose social status has been restored by Ahmadinejad. Rather, for their project they interviewed a diverse cross section of Iranian society : male and female students, young intellectuals and artists, minorities, impoverished people surviving on public welfare, couples in arranged marriages, religious pilgrims.

When Woods and Michel proposed the topic oftheir research to Iranians, the initial response was often incredulous: “Happiness? It doesn’t exist in this country!” The two then explained that the happiness they were speaking about was not shadi (joy), the kind shown on Western television commercials in Iran on the widely viewed satellite channels, but rather what Iranians call khoshbakhti (blessed happiness)—a more abstract, philosophical concept—generally interpreted as the comforting feeling of being in good company, among like-minded people, in this culture that has been preserved over centuries. Many of those they spoke with acknowledged the presence—despite the obvious social fragmentation because of class, religion, or political beliefs—of a kind of national harmony, one that Woods and Michel suggest is born of the unique set of cultural values—a national fabric—that holds people and country together:

The first of these values is Shiism, the distinctly Persian brand of Islam that joins religion, tradition, and national identity. Iranians still love their imams, their shrines, and their religious festivities— despite their faith being politicized for the last three decades. Then comes the family, which seems more important to many Iranians than aspirations like political freedom. Also—this is a country where taxi drivers happily recite their own verses, and where Hafez and Omar Khayyam are still best sellers: the Iranians have a threeainJ'emialiAiiayyälll aie SLIM UtSL StMietS. Lilt! irddlcHUs NcIVé cl tnfêSmillennia-old collective memory that has bred a love for beauty and poetry that is still very present in everyday life.

Paolo Woods’s photographs in these pages—featuring, among others, a female dentist, a teenager heavily influenced by American culture, an art teacher, a carpet salesman, and a man who leads self-help groups in the art of laughter—are not intended to provide a comprehensive portrait of a nation, but to offer a glimpse of a citizenry that is multifarious, modern, and complex.Q

—The Editors

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

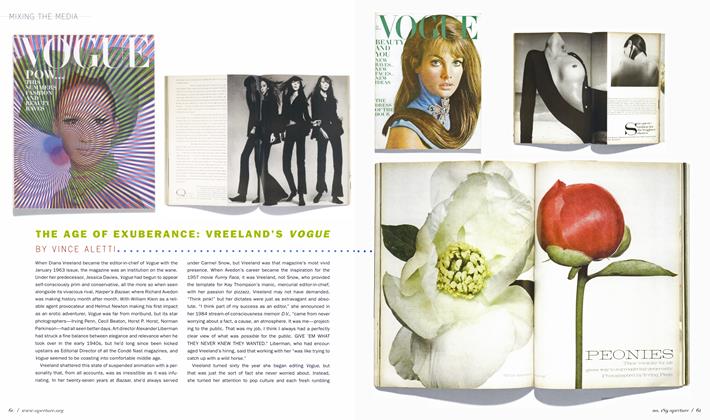

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaThe Age Of Exuberance: Vreeland's Vogue

Winter 2007 By Vince Aletti -

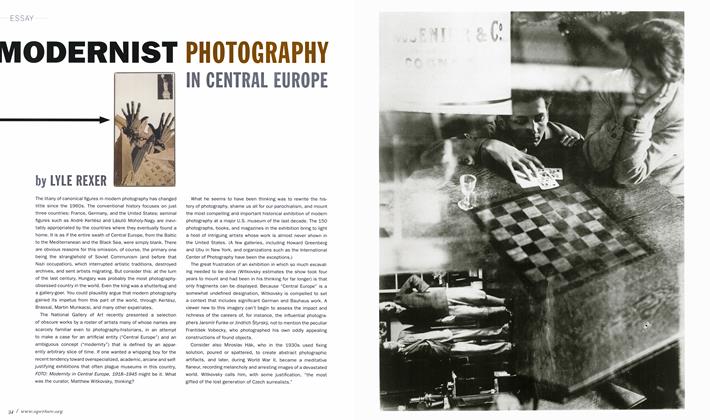

Essay

EssayModernist Photography In Central Europe

Winter 2007 By Lyle Rexer -

On Location

On LocationDawoud Bey's Harlem

Winter 2007 By Arthur C. Danto -

Archive

ArchiveBack In The Gdr

Winter 2007 By Jason Oddy -

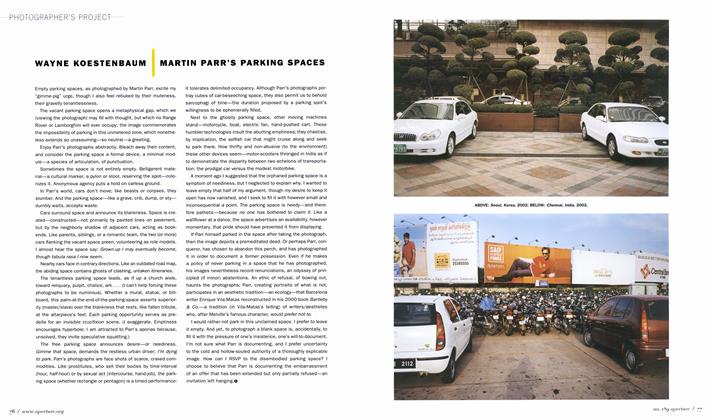

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectMartin Parr’s Parking Spaces

Winter 2007 By Wayne Koestenbaum -

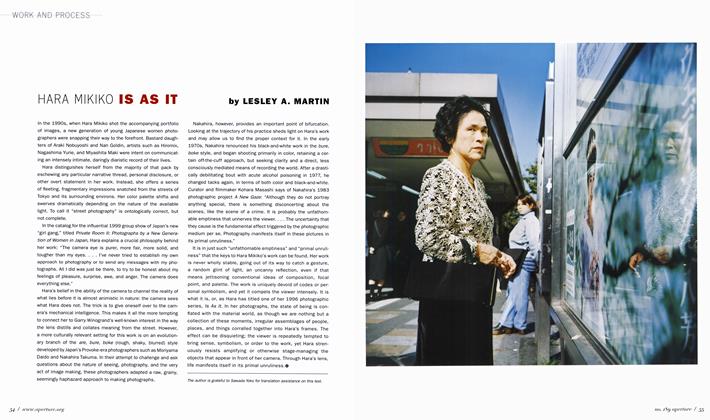

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHara Mikiko Is As It

Winter 2007 By Lesley A. Martin

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Paolo Woods

Serge Michel

Work In Progress

-

Work In Progress

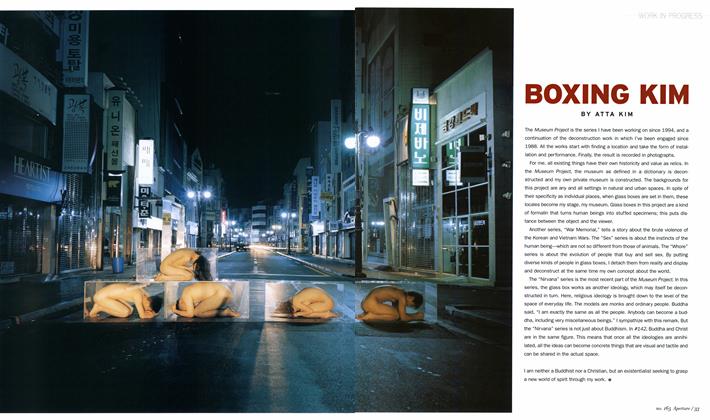

Work In ProgressBoxing Kim

Winter 2001 By Atta Kim -

Work In Progress

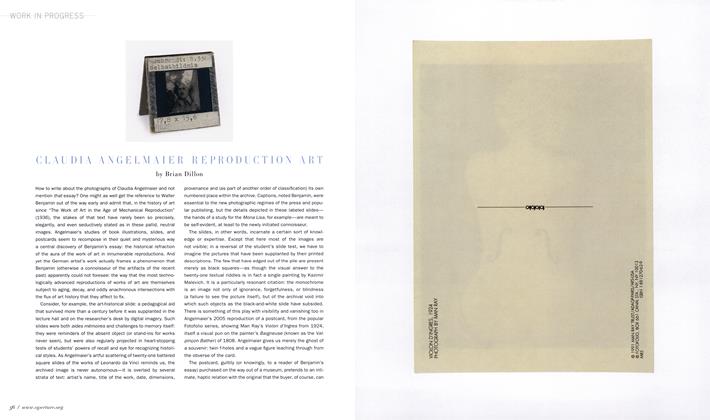

Work In ProgressClaudia Angelmaier Reproduction Art

Fall 2008 By Brian Dillon -

Work In Progress

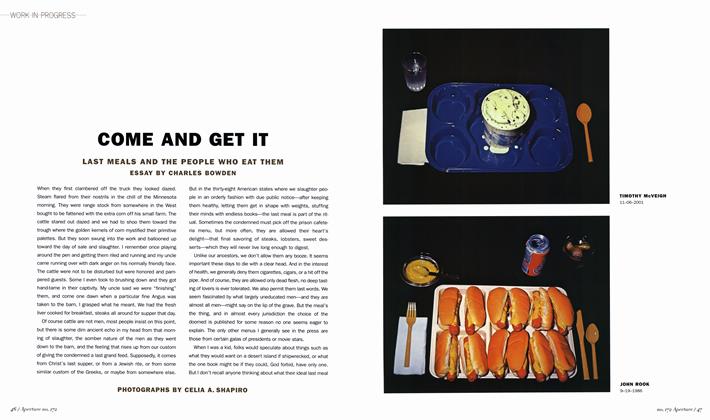

Work In ProgressCome And Get It

Fall 2003 By Charles Bowden -

Work In Progress

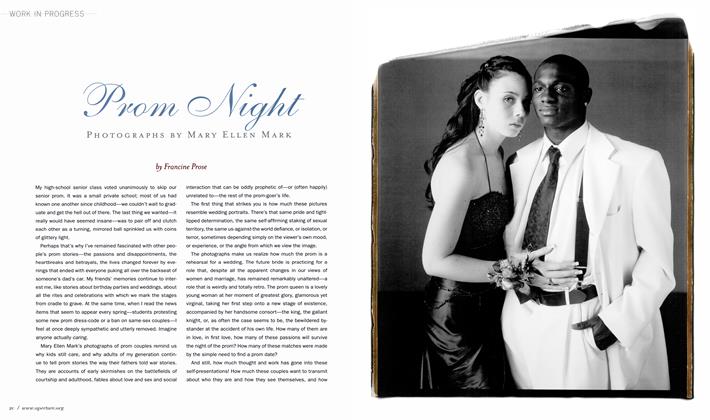

Work In ProgressProm Night

Summer 2007 By Francine Prose -

Work In Progress

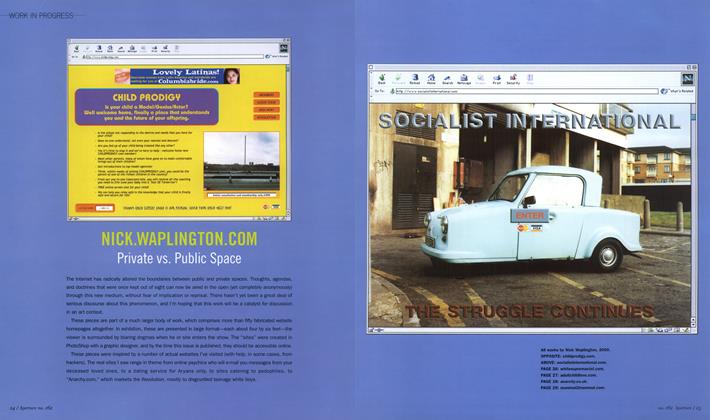

Work In ProgressNick.Waplington.Com

Winter 2001 By Nick Waplington -

Work In Progress

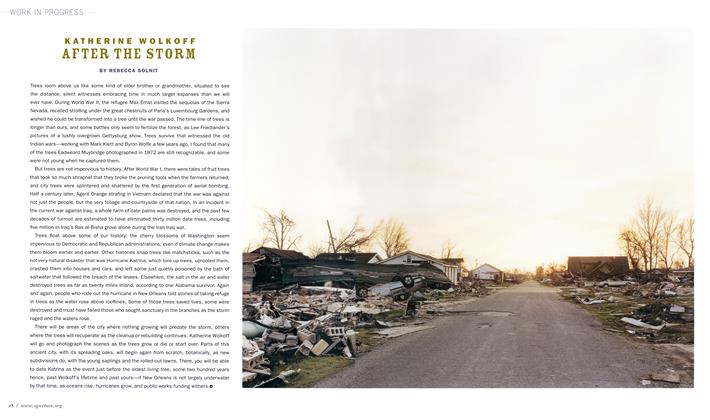

Work In ProgressAfter The Storm

Fall 2006 By Rebecca Solnit