MARTIN PARR’S PARKING SPACES

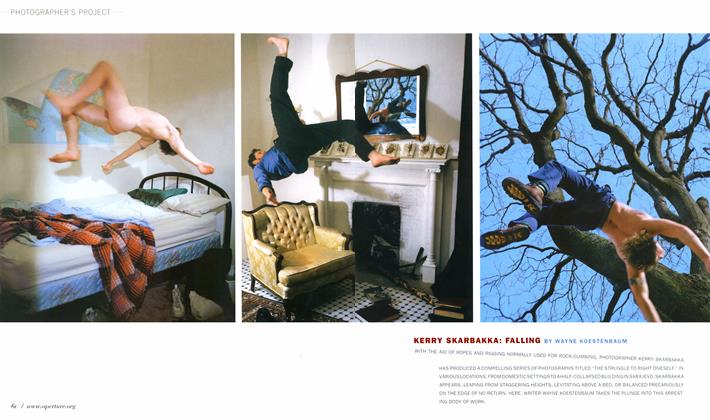

PHOTOGRAPHER'S PROJECT

WAYNE KOESTENBAUM

Empty parking spaces, as photographed by Martin Parr, excite my "gimme-pig" urge, though I also feel rebuked by their muteness, their gravelly tenantlessness.

The vacant parking space opens a metaphysical gap, which we (viewing the photograph) may fill with thought, but which no Range Rover or Lamborghini will ever occupy; the image commemorates the impossibility of parking in this unmetered zone, which nonetheless extends so unassuming—so neutral—a greeting.

Enjoy Parr’s photographs abstractly. Bleach away their content, and consider the parking space a formal device, a minimal module—a species of articulation, of punctuation.

Sometimes the space is not entirely empty. Belligerent material—a cultural marker, a pylon or stool, reserving the spot—colonizes it. Anonymous agency puts a hold on earless ground.

In Parr’s world, cars don’t move; like beasts or corpses, they slumber. And the parking space—like a grave, crib, dump, or sty— dumbly waits, accepts waste.

Cars surround space and announce its blankness. Space is created—constructed—not primarily by painted lines on pavement, but by the neighborly shadow of adjacent cars, acting as bookends. Like parents, siblings, or a romantic team, the two (or more) cars flanking the vacant space preen, volunteering as role models.

I almost hear the space say: Grown-up I may eventually become, though tabula rasa I now seem.

Nearby cars face in contrary directions. Like an outdated road map, the abiding space contains ghosts of clashing, untaken itineraries.

The tenantless parking space leads, as if up a church aisle, toward reliquary, pulpit, chalice, ark ... (I can’t help forcing these photographs to be numinous). Whether a mural, statue, or billboard, this palm-at-the-end-of-the-parking-space asserts superiority (master/slave) over the blankness that rests, like fallen tribute, at the altarpiece’s feet. Each parking opportunity serves as predella for an invisible crucifixion scene. (I exaggerate. Emptiness encourages hyperbole; I am attracted to Parr’s aporias because, unsolved, they invite speculative squatting.)

The free parking space announces desire—or neediness. Gimme that space, demands the restless urban driver; I’m dying to park. Parr’s photographs are face shots of scarce, craved commodities. Like prostitutes, who sell their bodies by time-interval (hour, half-hour) or by sexual act (intercourse, hand-job), the parking space (whether rectangle or pentagon) is a timed performance: it tolerates delimited occupancy. Although Parr’s photographs portray cubes of car-beseeching space, they also permit us to behold sarcophagi of time—the duration proposed by a parking spot’s willingness to be ephemerally filled.

Next to the ghostly parking space, other moving machines stand—motorcycle, boat, electric fan, hand-pushed cart. These humbler technologies insult the abutting emptiness; they chastise, by implication, the selfish car that might cruise along and seek to park there. How thrifty and non-abusive (to the environment) these other devices seem—motor-scooters thronged in India as if to demonstrate the disparity between two echelons of transportation: the prodigal car versus the modest motorbike.

A moment ago I suggested that the orphaned parking space is a symptom of neediness, but I neglected to explain why. I wanted to leave empty that half of my argument, though my desire to keep it open has now vanished, and I seek to fill it with however small and inconsequential a point. The parking space is needy—and therefore pathetic—because no one has bothered to claim it. Like a wallflower at a dance, the space advertises an availability, however momentary, that pride should have prevented it from displaying.

If Parr himself parked in the space after taking the photograph, then the image depicts a premeditated deed. Or perhaps Parr, conqueror, has chosen to abandon this perch, and has photographed it in order to document a former possession. Even if he makes a policy of never parking in a space that he has photographed, his images nevertheless record renunciations, an odyssey of principled (if minor) abstentions. An ethic of refusal, of bowing out, haunts the photographs; Parr, creating portraits of what is not, participates in an aesthetic tradition—an ecology—that Barcelona writer Enrique Vila-Matas reconstructed in his 2000 book Bartleby & Co.—a tradition (in Vila-Matas’s telling) of writers/aesthetes who, after Melville’s famous character, would prefer not to.

I would rather not park in this unclaimed space. I prefer to leave it empty. And yet, to photograph a blank space is, accidentally, to fill it with the pressure of one’s insistence, one’s will-to-document. I’m not sure what Parr is documenting, and I prefer uncertainty to the cold and hollow-souled authority of a thoroughly explicable image. How can I RSVP to the disembodied parking space? I choose to believe that Parr is documenting the embarrassment of an offer that has been extended but only partially refused—an invitation left hanging.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressKhoshbakhti "Blessed Happiness" In Iran

Winter 2007 By Paolo Woods, Serge Michel -

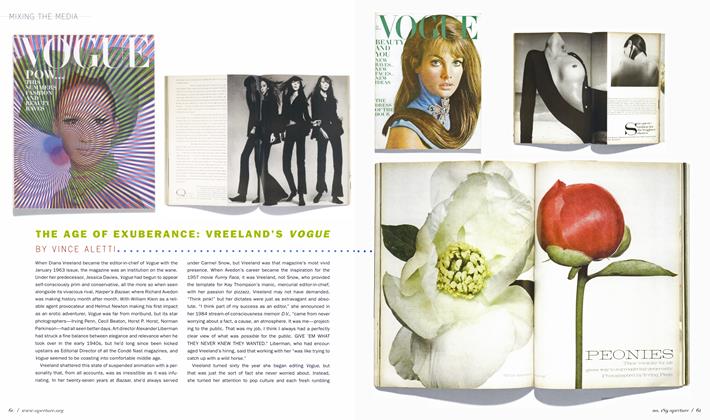

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaThe Age Of Exuberance: Vreeland's Vogue

Winter 2007 By Vince Aletti -

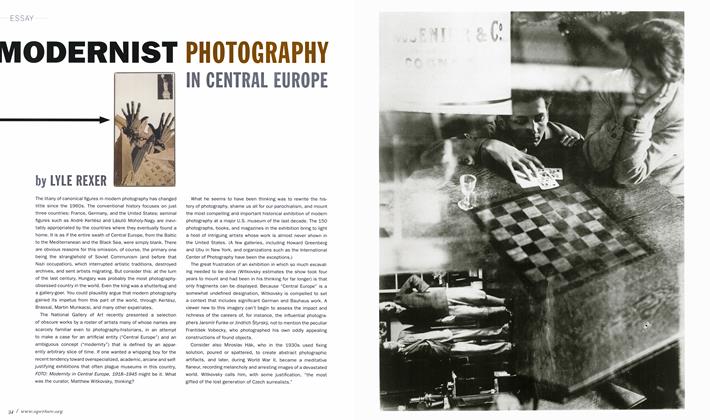

Essay

EssayModernist Photography In Central Europe

Winter 2007 By Lyle Rexer -

On Location

On LocationDawoud Bey's Harlem

Winter 2007 By Arthur C. Danto -

Archive

ArchiveBack In The Gdr

Winter 2007 By Jason Oddy -

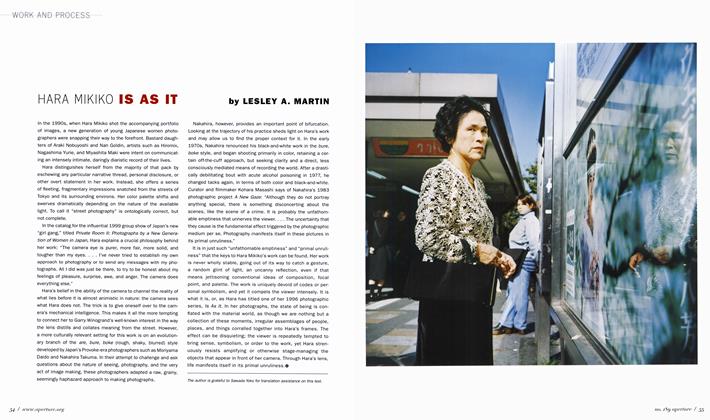

Work And Process

Work And ProcessHara Mikiko Is As It

Winter 2007 By Lesley A. Martin

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Wayne Koestenbaum

Photographer's Project

-

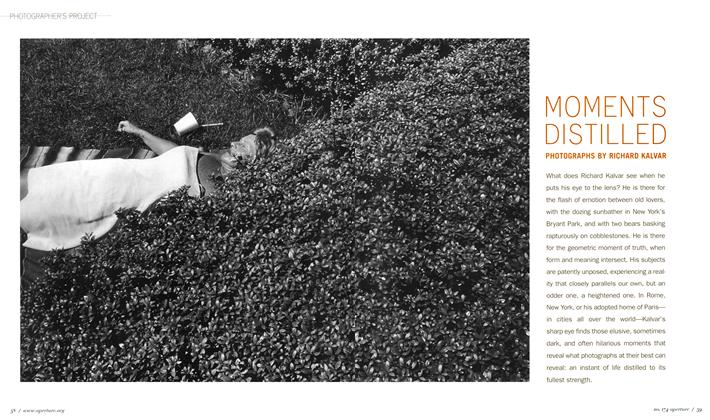

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectMoments Distilled: Photographs By Richard Kalvar

Spring 2004 -

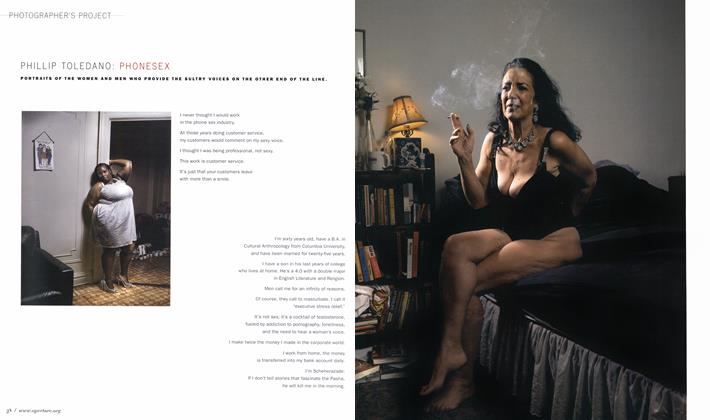

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectPhillip Toledano: Phonesex

Winter 2008 -

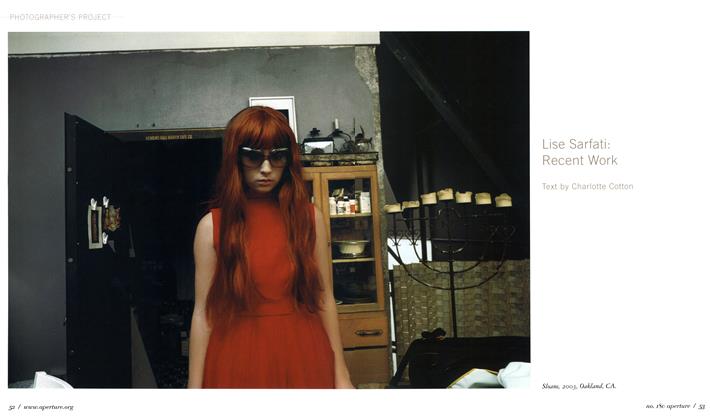

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectLise Sarfati: Recent Work

Fall 2005 By Charlotte Cotton -

Photographer's Project

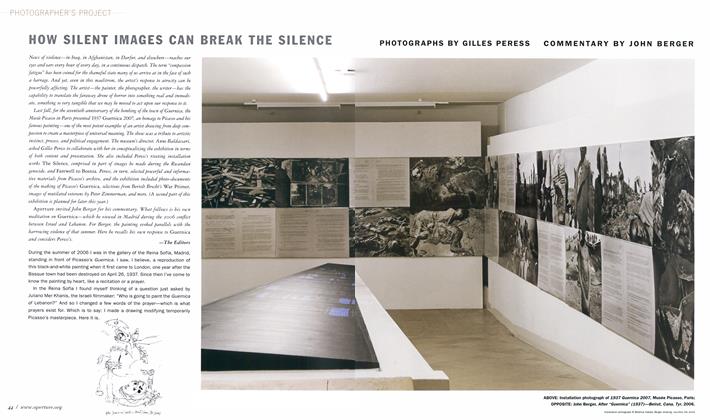

Photographer's ProjectHow Silent Images Can Break The Silence

Summer 2008 By John Berger -

Photographer's Project

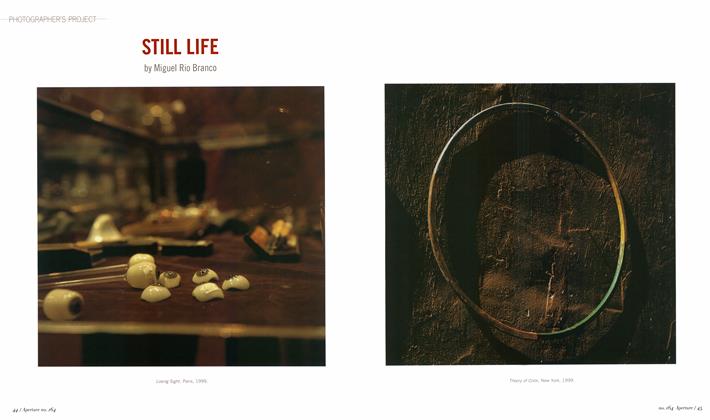

Photographer's ProjectStill Life

Summer 2001 By Miguel Rio Branco -

Photographer's Project

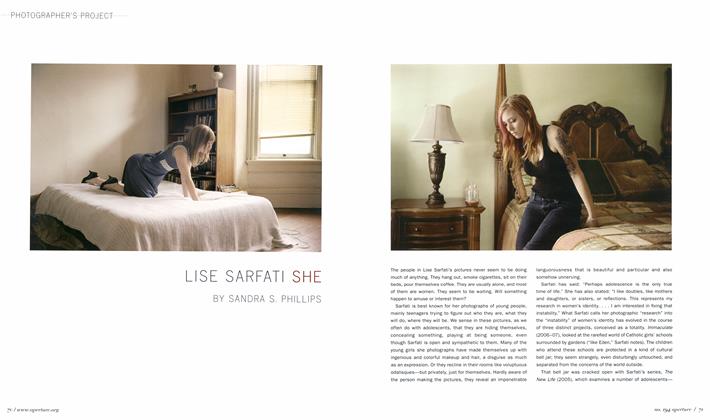

Photographer's ProjectLise Sarfati She

Spring 2009 By Sandra S. Phillips