ROADS LESS TRAVELED

A CRUDE WORLD

SERGE ENDERLIN

SERGE MICHEL

PAOLO WOODS

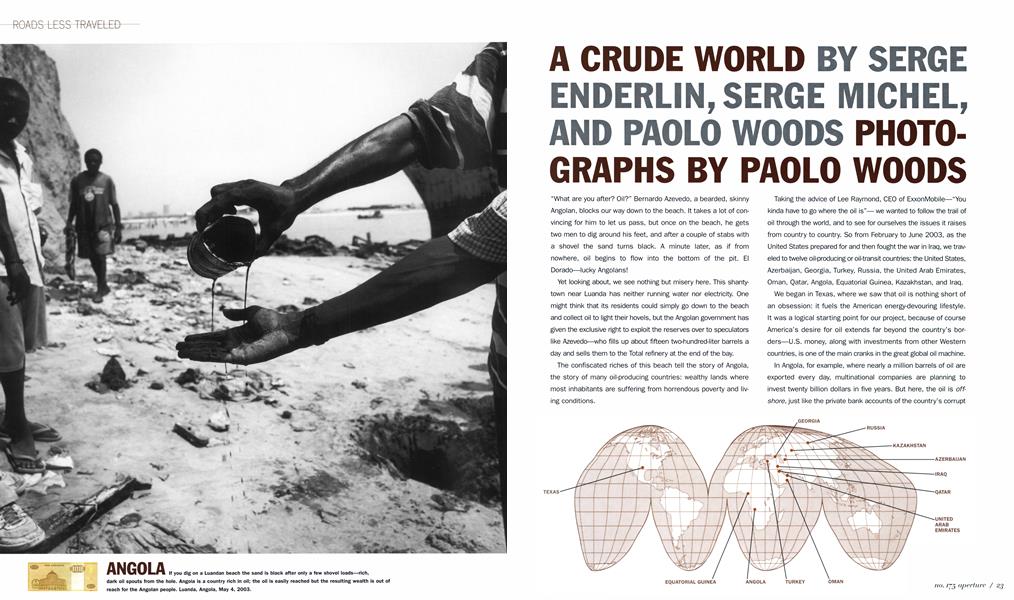

"What are you after? Oil?" Bernardo Azevedo, a bearded, skinny Angolan, blocks our way down to the beach. It takes a lot of convincing for him to let us pass, but once on the beach, he gets two men to dig around his feet, and after a couple of stabs with a shovel the sand turns black. A minute later, as if from nowhere, oil begins to flow into the bottom of the pit. El Dorado—lucky Angolans!

Yet looking about, we see nothing but misery here. This shantytown near Luanda has neither running water nor electricity. One might think that its residents could simply go down to the beach and collect oil to light their hovels, but the Angolan government has given the exclusive right to exploit the reserves over to speculators like Azevedo—who fills up about fifteen two-hundred-liter barrels a day and sells them to the Total refinery at the end of the bay.

The confiscated riches of this beach tell the story of Angola, the story of many oil-producing countries: wealthy lands where most inhabitants are suffering from horrendous poverty and living conditions.

Taking the advice of Lee Raymond, CEO of ExxonMobile—“You kinda have to go where the oil is”— we wanted to follow the trail of oil through the world, and to see for ourselves the issues it raises from country to country. So from February to June 2003, as the United States prepared for and then fought the war in Iraq, we traveled to twelve oil-producing or oil-transit countries: the United States, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, Russia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Qatar, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Kazakhstan, and Iraq.

We began in Texas, where we saw that oil is nothing short of an obsession: it fuels the American energy-devouring lifestyle. It was a logical starting point for our project, because of course America’s desire for oil extends far beyond the country’s borders—U.S. money, along with investments from other Western countries, is one of the main cranks in the great global oil machine.

In Angola, for example, where nearly a million barrels of oil are exported every day, multinational companies are planning to invest twenty billion dollars in five years. But here, the oil is offshore, just like the private bank accounts of the country’s corrupt leaders. The rest of the Angolans, twelve million of them, are onshore, so—although there is so much suffering and strife here—the oil money doesn’t touch them.

The global hunger for oil extends also to Equatorial Guinea. The big U.S. companies, established here after 1998, have already poured five billion dollars into the country’s coffers. If the total investments of the past six years were divided among the population (about half a million people), the inhabitants of Equatorial Guinea could have the same standard of living as the Swiss—but here, you divide by only one, namely the country’s president, Teodoro Obiang Nguema. Considered a dictatorship by international organizations, Equatorial Guinea is courted by Washington; last year, the United States reopened its Malabo embassy, which had been closed since 1996.

On the shores of the Caspian Sea, in the post-Soviet colossus of Kazakhstan, the Chevron group works the Tengiz deposits. Offshore, the Italian Agip group is running the consortium that before long will begin to fill the first barrels from the enormous well of Kashagan. Nursultan Nazarbayev, the man presiding over the destiny of this ex-Soviet republic, is often described as an “enlightened despot”—although he frequently confuses his country’s finances with those in his own pocket.

Money flows from all corners: British Petroleum is the leading company behind the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, running from the Caspian Sea to the Mediterranean. And Azerbaijan has been attracting Western investment for ten years. Yet the Azeri men who repair the plants of the old Bibi Heybat oil field south of Baku are paid no more than sixty dollars a month. They are waiting for the construction of the pipeline that will reach Ceyhan on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey. But will this really bring riches to the Azeri? For now, most of them survive thanks only to money sent by their cousins living in exile in Russia.

In Siberian villages where black gold is extracted, people are a bit better off than they were in earlier days, and the billions of incoming oil dollars restore to Moscow a little of the power it lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Private companies, run by the new Russians, the oligarchs, dominate the landscape. But the world of oil is rife with corruption. As we were leaving for the next leg of our tour of the oil world, Vladimir Putin ordered Russian prosecutors to investigate Mikhail Khodorkovsky (owner of the Yukos oil company—the fourth largest in the world) on allegations of tax evasion and theft of state property, and the tycoon was arrested by security police in October 2003.

The indigenous peoples of Siberia have firsthand experience with the nature of oilmen. In the ancestral lands that local tribes have been forced to leave, oil derricks have replaced reindeer-skin tents. The oil that has begun to spout everywhere has killed the trout in their holy rivers. The Khanti, one of many indigenous tribes, were promised a “new life” by the oil companies; they were given cases of vodka—a cynical gesture of offering indeed.

The last stop on our oil odyssey was Iraq, where many inhabitants are convinced that it’s only oil that interests the Americans who are now ostensibly offering the country democracy and development. When the Iraqi regime fell last year, the sole ministry building to escape looting was that of the Oil Ministry. Two months later, when Baghdad was still without electricity or fuel, we visited Kirkuk, one of the most prolific oil fields in the world. There we saw American engineers installing Korean airconditioning units in offices that had already been fully restored. Depressed GIs told us they were anxious to get back to the States. But at the rate at which the international oil empire spreads to the four corners of the globe, it will be long before they see home.

Can a treasure like oil be a curse? We saw, in every country we visited, that people will go to any lengths for it: where there is oil, there is corruption, poverty, and often war. In the early 1970s, Juan Pablo Perez Alfonso, the Venezuelan Energy Minister and a cofounder of OPEC, coined a phrase that still rings true: “Oil ... is the devil’s excrement.”©

Un Monde de Brut, the book on this project, was published last year by Éditions du Seuil, Paris.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Work And Process

Work And ProcessElemental Vision: Matter, Paradox And Other Absorptions Of Doug And Mike Starn

Summer 2004 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

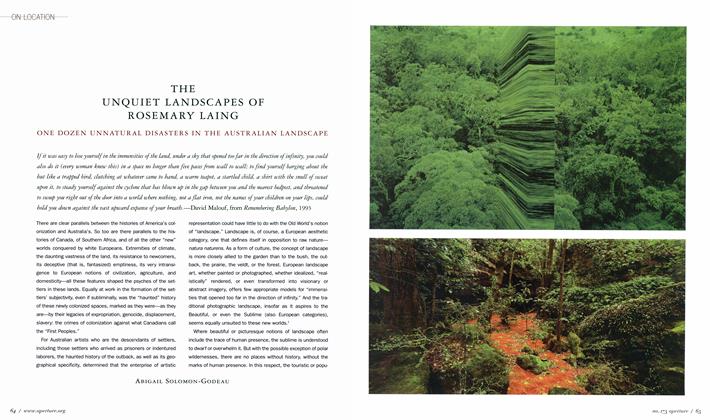

On LocationThe Unquiet Landscapes Of Rosemary Laing

Summer 2004 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

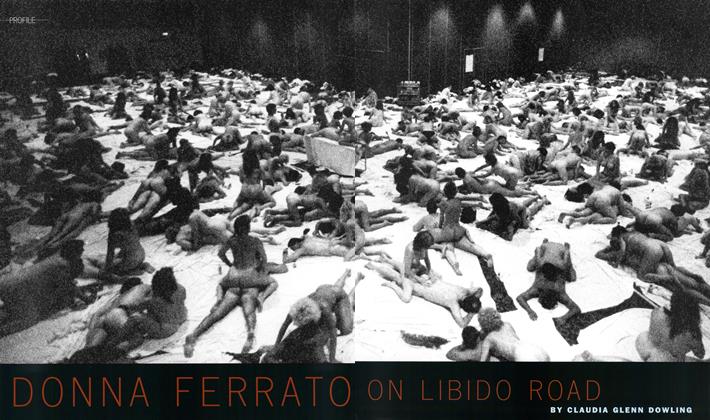

Profile

ProfileDonna Ferrato On Libido Road

Summer 2004 By Claudia Glenn Dowling -

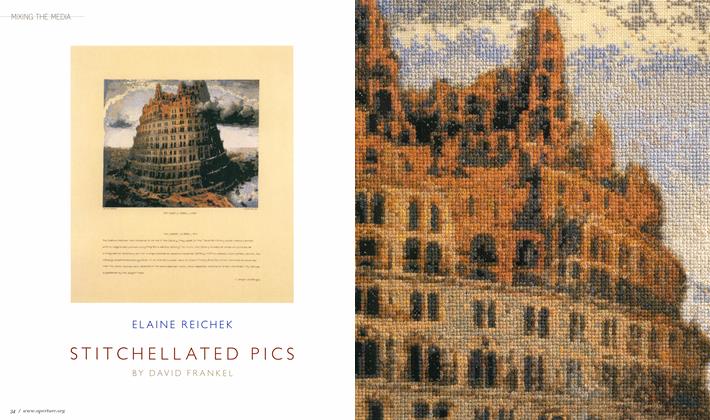

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaElaine Reichek Stitchellated Pics

Summer 2004 By David Frankel -

Meetings

Meetings10 Years: From Analog To Digital: Zonezero

Summer 2004 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Notes

NotesNotes

Summer 2004

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Paolo Woods

Serge Michel

Roads Less Traveled

-

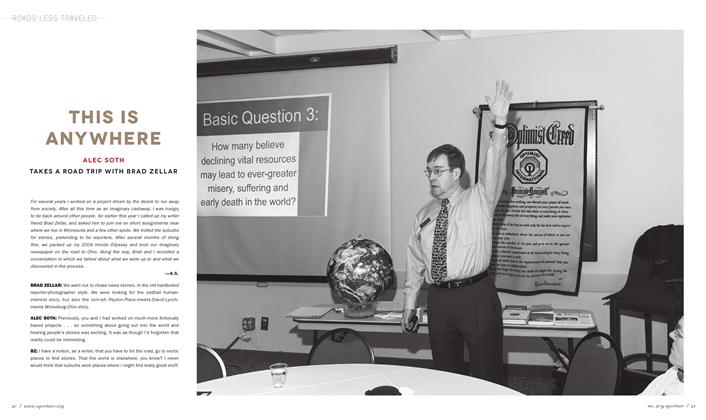

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledThis Is Anywhere

Winter 2012 By Alec Soth -

Roads Less Traveled

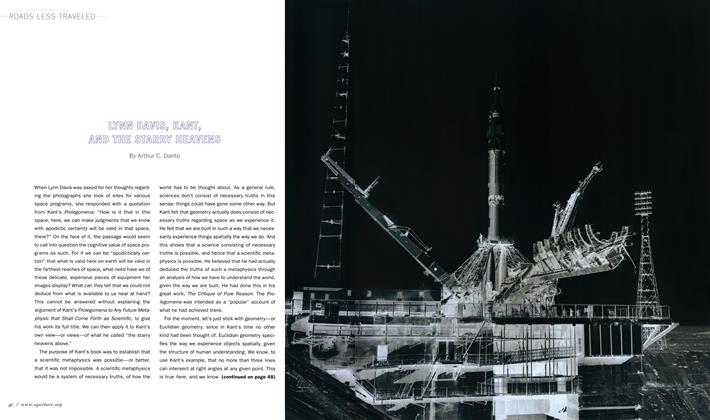

Roads Less TraveledLynn Davis, Kant, And The Starry Heavens

Spring 2006 By Arthur C. Danto -

Roads Less Traveled

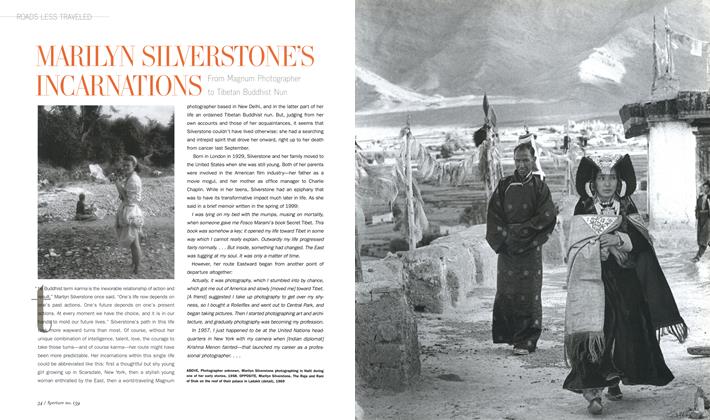

Roads Less TraveledMarilyn Silverstone’s Incarnations

Spring 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Roads Less Traveled

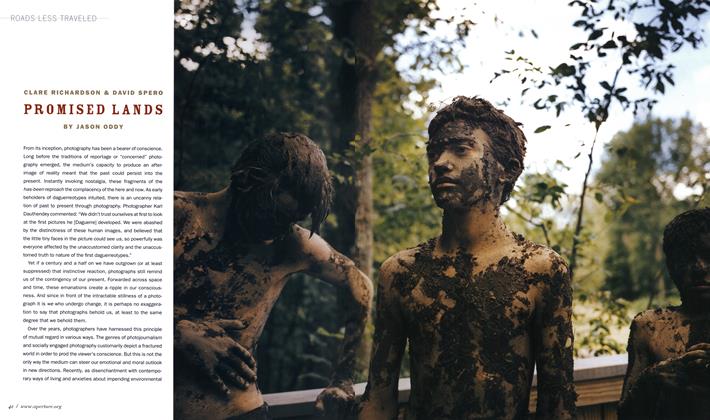

Roads Less TraveledClare Richardson & David Spero Promised Lands

Spring 2007 By Jason Oddy -

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledDisappearing Giants

Winter 2008 By Michael "Nick" Nichols -

Roads Less Traveled

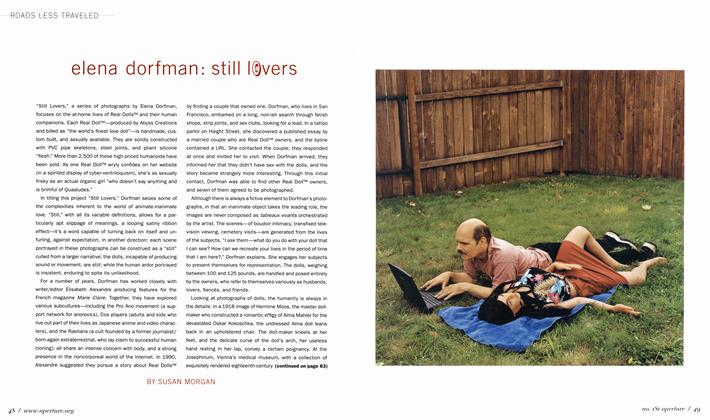

Roads Less TraveledElena Dorfman: Still Lovers

Winter 2005 By Susan Morgan