THE FIRST GUANGZHOU PHOTO BIENNIAL

REVIEWS

Guangzhou, the bustling Chinese metropolis once known as Canton, lies just inland from Hong Kong on the Pearl River. It has lately seen its skyline soar and its fortunes rise in unison with the continuing boom in the nearby "special economic zones" of the Pearl River Delta. Surprisingly, this supremely commercial city is emerging as a southern cultural center eager to challenge Beijing and Shanghai. In 2002, the regional Guangdong Museum of Art launched an ambitious triennial exhibition of international contemporary art; this November’s installment will be directed by high-profile curators Hans-Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanrou, working with architect Rem Koolhaas. In early 2004, the same museum decided to establish an international photography biennial. Reflecting the breakneck pace that is now customary in China, the Guangzhou Photo Biennial opened its doors less than a year later, in mid January 2005.

Titled “Re-Viewing the City,” the biennial was curated by Gu Zheng, a theoretically minded professor from the Fudan University in Shanghai, and Alain Jullien, a French photography curator and festival organizer. A few years back, Jullien was instrumental in setting up the annual photography festival in Pingyao, a lovely but alarmingly remote historic city in China’s Shanxi province. Like Pingyao, the Guangzhou biennial closely followed the Arles formula, featuring a cluster of large thematic group exhibitions, roughly fifty concentrated gatherings of works by individual photographers, and an evening of projection pieces; all took place in the spacious, modern galleries of the Guangdong Museum of Art and the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. While the majority of the 140 biennial participants were Chinese, there was a clear effort to offer the Guangzhou audience a generous sampling of classic twentieth-century world photography, by such figures as Lisette Model, Daido Moriyama, and Elliott Erwitt.

The biennial’s bland title belied the urgency of its real theme: China’s tumultuous shift from a rural to an urban society. Each year, China’s metropolitan centers are swelled by some twenty million new inhabitants, placing enormous strains on city dwellers and on the existing urban infrastructure. Adding to the tension is the presence of millions of internal migratory laborers, who are drawn from the countryside by the prospect of temporary construction or factory jobs, and who can count on little official protection from the harsh treatment they often encounter. These conditions have attracted the attention of a new generation of Chinese social-documentary photographers, and nowhere more than in Guangzhou, where the news media has a reputation for the dogged pursuit of instances of corruption and exploitation.

If the biennial organizers made one miscalculation, it was to play off within the same galleries the urban-theme works of documentary-style photographers and those of China’s remarkable young photographer-artists. The result was an awkward imbalance, with the typically modest, often black-and-white photographs of the documentary group being overpowered by the spectacular, mural-sized color prints of such internationally established artists as Xing Danwen, Wang Qingsong, and Miao Xiaochun, and by the quirky photoobjects of Bai Yiluo and Wang Ningde. In consequence, it was easy to overlook the somber portraits of Chinese mentally disturbed street people by Zeng Yicheng; the unnerving observations of the behavior of animals in China’s zoos by Xue Ting; and the fascinating series of color portraits of today’s Shanghai residents by Hu Yang. Yet these works, by independent reportage photographers whose images seldom attract attention outside China, counted among the real discoveries of the biennial.

The prospects of social-documentary photography in a changing but still authoritarian China provided the burning topic of the panel discussions that accompanied the biennial’s opening. Although a handful of foreign scholars took part, these sessions mostly consisted of a remarkably freewheeling discussion among Chinese about the future of photography in their country. Speaker after speaker hailed photography’s ability to lay bare the stark inequities and burgeoning social problems that have been spawned by China’s current urban transformation. Again and again, photography was linked to the defense of the “rights of the powerless,” and photographers were urged to provide a voice for the countless city-dwellers who have been pushed aside by big real-estate developers, investors, and local politicians. At one point Chen Danqing, a painter who teaches at Tsinghua University in Beijing, mordantly observed that in China’s new cities, "the only right we have left is the right to view,” and he wryly thanked photographers for preserving that right.

Such heated rhetoric notwithstanding, it should be observed that few of the exhibiting photographers dealt openly with the truly explosive urban social issues affecting China, such as the spread of AIDS. And almost none of the Chinese panelists showed more than a dim awareness of the rise and fall of social documentary photography in the West. If the 2007 Guangzhou Photo Biennial can find a way to address such wider questions, the exhibition could be an event of historic importance in China.©

Christopher Phillips

The Guangzhou Photo Biennial took place January 18-February 27, 2005.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

On Assignment

On AssignmentSurveillance

Summer 2005 By Michael Persson -

Archive

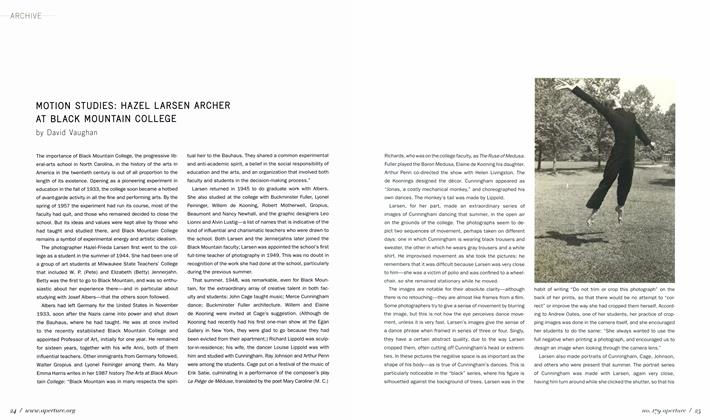

ArchiveMotion Studies: Hazel Larsen Archer At Black Mountain College

Summer 2005 By David Vaughan -

Dialogue

DialogueUnpacking My Library

Summer 2005 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Witness

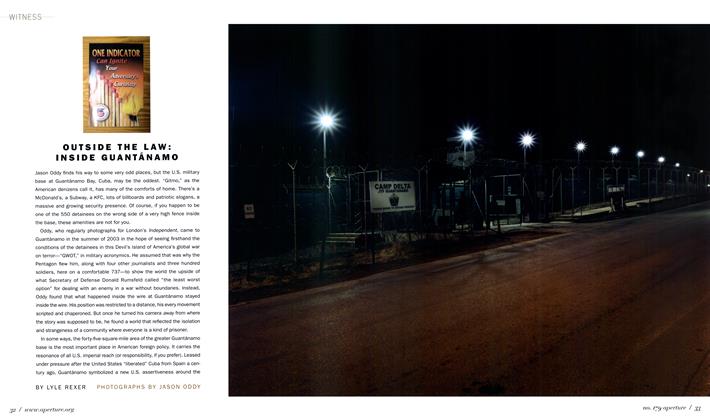

WitnessOutside The Law: Inside Guantánamo

Summer 2005 By Lyle Rexer -

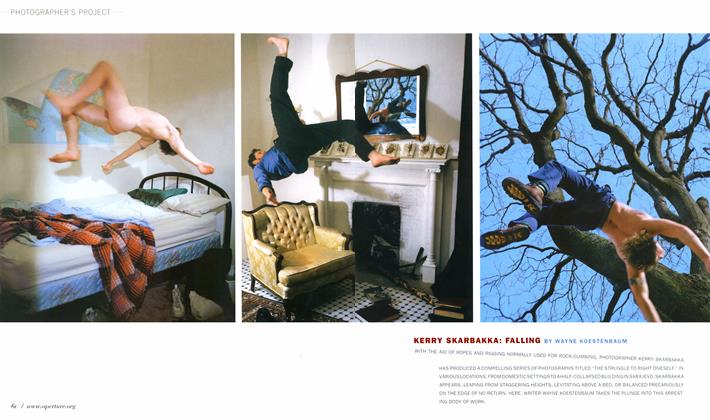

Photographer's Project

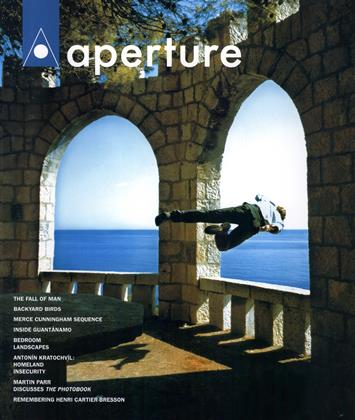

Photographer's ProjectKerry Skarbakka: Falling

Summer 2005 By Wayne Koestenbaum -

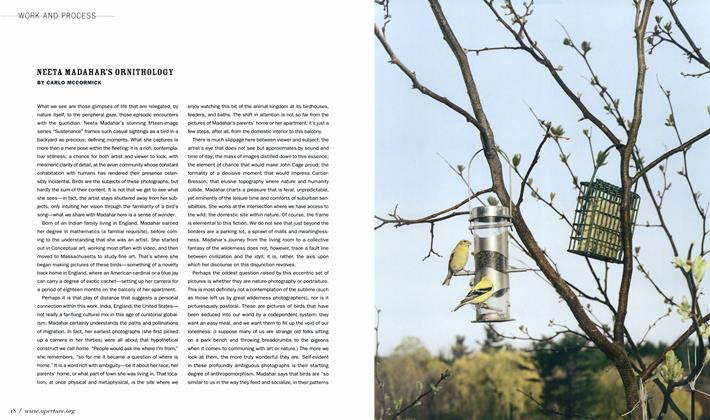

Work And Process

Work And ProcessNeeta Madahar's Ornithology

Summer 2005 By Carlo McCormick

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Christopher Phillips

-

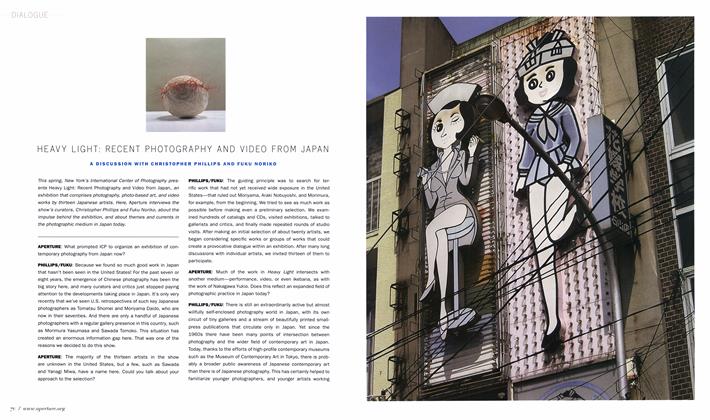

Dialogue

DialogueHeavy Light: Recent Photography And Video From Japan

Summer 2008 -

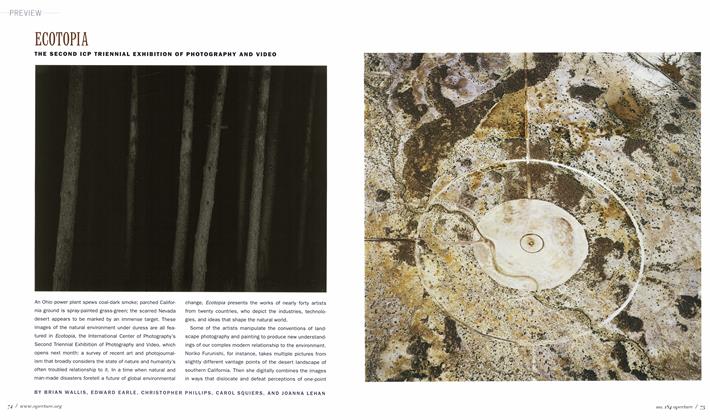

Preview

PreviewEcotopia

Fall 2006 By Brian Wallis, Edward Earle, Christopher Phillips, 2 more ... -

Reviews

ReviewsThree Shadows

Spring 2008 By Christopher Phillips -

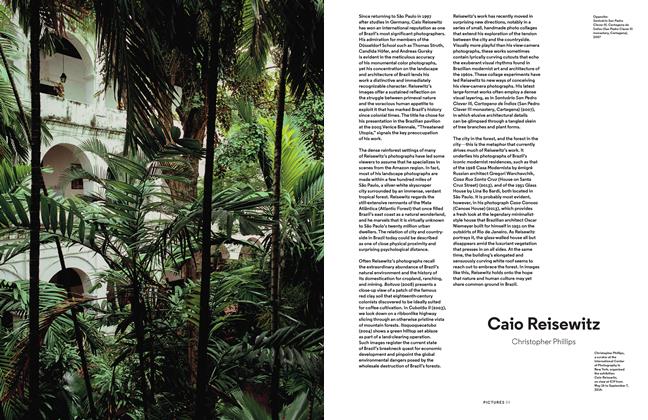

Pictures

PicturesCaio Reisewitz

Summer 2014 By Christopher Phillips -

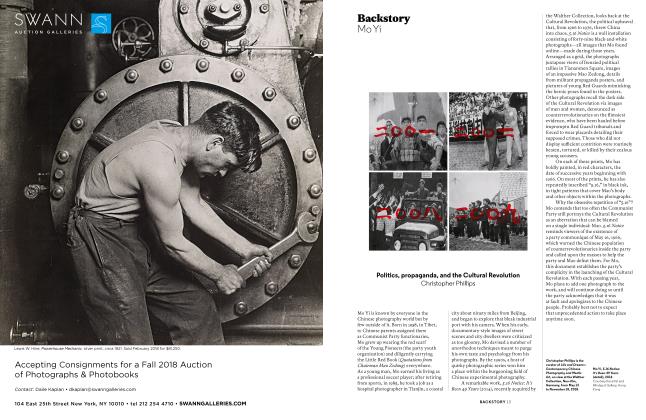

Backstory

BackstoryMo Yi

Summer 2018 By Christopher Phillips

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsBill Henson: 3 Decades Of Photography

Fall 2005 By Felicity Fenner -

Reviews

ReviewsPhotography And The Private Collector

Summer 1970 By John Szarkowski -

Reviews

ReviewsStarburst: Color Photography In America, 1970-1980

Spring 2011 By Laurie Dahlberg -

Reviews

ReviewsShomei Tomatsu: Skin Of The Nation

Spring 2005 By Lyle Rexer -

Reviews

ReviewsHelios: Eadweard Muybridge In A Time Of Change

Winter 2010 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsStreet Credibility

Fall 2004 By Walead Beshty