Photography and the Private Collector

Before discussing the collecting of photographs specifically, it might be useful to say a very few words about collecting in general. One must begin by stating that collecting is in itself not necessarily a virtue. One might go further, and admit that the collecting habit, in its advanced stages, can lead to the mortal sin of greed (coveting one's neighbor's goods), and to the related lesser transgressions of avarice, jealousy, cupidity, and income tax evasion.

Nevertheless, we will surely admit that much of what we know about the world is derived from works of art that were preserved in private collections; and it would be gratuitous to carp simply because these collections may have been built on a foundation of mixed motives. Why Lorenzo de Medici (or Dr. Barnes) collected is less important from the point of view of own selfish interests than the fact that they did collect, and did so with intelligence, discrimination, and passion.

It should by this date be possible to define with some precision the character of an ideal collector. He should combine the qualities of an amateur, a critic, a curator, a magpie, and an adventurer. (Adventurer is I think a more felicitous word than gambler.) From this list of qualifications I have omitted investor, since it seems clear that in the long run collecting pictures is just as undependable a way of building one’s substance as is the purchase of real estate, mutual funds, or policemen.*

This working definition would seem to hold true for a collector or prospective collector of photographs. Let us consider the criteria one by one. AMATEUR. If one does not love photographs, it is unnecessary to proceed further. Quality is not the issue here: if the homely charm and blatant pathos of a family album escape the would-be collector, then the intelligence of Walker Evans and the hedonism of Edward Weston will also, for these are all equally photographs.

CRITIC. The collector of photographs can at this date expect precious little help from professional critics. Photographic criticism is sparse in quantity and generally disappointing in quality. We can hope that the future will see the development of a sizable and responsible group of photography critics, who will respond to the efforts of photographers with intelligence, knowledge, good will, eyes, viscera, and a basic command of at least one language. In the meantime the collector can take added satisfaction from the fact that he is a pioneer, dependent in large measure on his own research and his own sensibility, and responsible for his own triumphs and his own mistakes, (see ADVENTURER.)

CURATOR. The serious collector of photographs should also acquire a basic knowledge of the fundamental questions that scholars ask of a picture. These simple intellectual tools are in reality more a matter of discipline and orderly procedure than of sensibility or arcane knowledge; when was the print (as well as the negative) made? And by whom? And by what process? These questions are especially relevant if the date of the print is significantly different than the date of the negative. In the case of contemporary work, it seems reasonable that a collector’s print should be signed and dated—if not on the front, then on the back—to demonstrate that the photographer by his own standards found it worthy of his imprimatur.

Collectors of the traditional graphic media generally don’t understand that a photographic print is a much less predictable product than a print from an engraving or etching plate, or a lithographic stone. While the older processes are based fundamentally on yes or no signals, the photographic negative is almost infinitely plastic, capable of yielding a very much broader range of response than the traditional multiple print media. This fact argues against the arbitrary limitations of an edition, for the photographer’s own understanding of his negative may be enriched (or impoverished) by time—and the chance of his being able truly to duplicate an earlier print is very slight indeed.

The collector should also be prepared to ask questions, within reason, concerning the degree of craft that was expended to make the print permanent. There has been a good deal of talk lately about this issue, and often cries of anguish when photographers are told that their pictures will not necessarily last forever. This is doubtless true, but to put the fact in perspective we might remind ourselves that even the Parthenon, after not even 2500 years, is in rather shabby condition. To say nothing of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building of 1904 (demolished); or Corbusier’s Villa Savoye of 1928 (desecrated); or Jean Tinguely’s self-destructing machine Hommage à New York of 1960 (successful); or the many paintings of the past twenty years that have been more profitable for their restorers than for their makers or owners. Two facts should be remembered here: (1) many photographic prints more than one hundred years old are in beautiful condition, and (2) Mark Twain said that for men, immortality meant thirty years.

It can also be assumed that a serious collector will learn a few basic rules concerning the preservation of photographs, and that he will learn to hate rubber cement, cheap mat board and masonite (both filled with sulphides), and damp storage areas. He will also learn that the surface of a photograph is physically fragile, and that unless framed under glass it should be protected from abrasion by a cut-out overlay mat. MAGPIE. The term is used here loosely, to stand for a spirit of generosity before the unaccepted. In an art which is much richer in achievement than in analysis, the collector can afford to give the benefit of the doubt to his intuitions. Less than a decade ago no survey of the history of photography mentioned these names: August Sander, E. J. Bellocq, Jacques Lartigue, Frances Johnston, William Notman, Adam Clark Vroman—to name a few—even though Lartigue, the youngest of these by a full generation, was born in 1896. Ten years from now, without doubt, new names will have been added to the list of those toward whom photographers will feel filial gratitude. ADVENTURER. There is as yet (happily) no reason why one should collect photographs unless one really wants to. When the last of the marginal Picasso lithographs and Nolde woodcuts and unapproved Rodin casts are finally ensconced in permanent collections, then the possession of a few Atgets or Westons will provide social cache; in the meantime the collector can buy what he likes and thinks good, without regard for their status value—and consequently at rational prices.

Most collectors will probably begin with photographs of established quality—and for this they should not be faulted. Familiarity with fine pictures breeds confidence, and confidence breeds independence. With confidence and independence, a collector can be as good as his talent allows. If he has good eyes and a good mind—and if he trusts them—he will build a great collection. At this point he surely has little competition.

Best of all, the private collector—unlike a museum, for example—need not try to be responsible to quality regardless of content; he can on the contrary indulge his own sensibility and his own prejudices. If he proves to be wrong in the eyes of history, his collection will still be eccentric and interesting; if history declares him right he will be a genius and a prophet. Surely neither option is to be scorned.

*Even the bluest chips among art works would seem undistinguished as investments. Rembrandt’s One Hundred Guilder Print sold for that price when new (about 1640), and for $32,500 (118,000 guilder) when auctioned in 1968. If the same 100 guilder had been invested in tulips, chocolate, and dike building, and had returned a profit of five per cent, compounded annually for a period of three hundred and thirty years, the accrued capital would now total over three and one third billion guilder, or about one billion dollars. (Since I have no notion of what has happened to the relative value of the guilder since 1640, the above figures are presumably meaningless.)

John Szarkowski

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

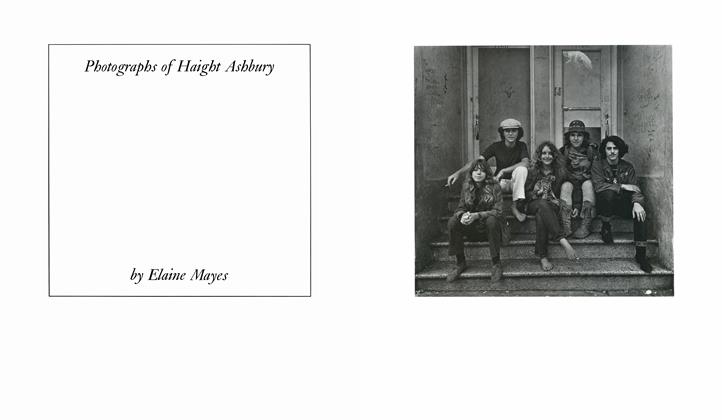

Photographs Of Haight Ashbury

Summer 1970 By Elaine Mayes, The Doors -

The Tale Of Peter Rasun Gould: An Experiment In Fiction

Summer 1970 By Minor White -

Pictures By Scott Hyde

Summer 1970 By Syl Labrot, Scott Hyde -

Summer 1970

Summer 1970 -

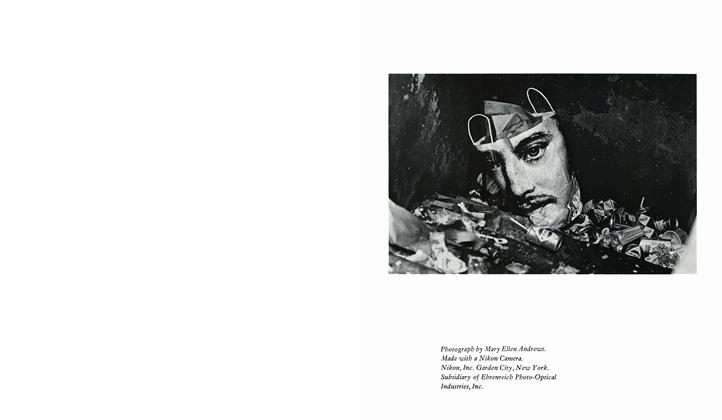

Photograph By Mary Ellen Andrews

Summer 1970 -

Photograph By Rosario Mazzeo.

Summer 1970

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

John Szarkowski

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsTwilight: Photography In The Magic Hour

Summer 2007 By Aaron Schuman -

Reviews

ReviewsMississippi Delta Photography

Fall 2007 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsThe Original Copy

Summer 2011 By Lyle Rexer -

Reviews

ReviewsDarkside Ii

Spring 2010 By Shelley Rice -

Reviews

ReviewsEvelyn Hofer Retrospective

Spring 2007 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

ReviewsFellini: La Grande Parade

Summer 2010 By Vicki Goldberg