Dialogue

Heavy Light: Recent Photography And Video From Japan

A DISCUSSION WITH CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS AND FUKU NORIKO

Summer 2008HEAVY LIGHT: RECENT PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO FROM JAPAN

DIALOGUE

A DISCUSSION WITH CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS AND FUKU NORIKO

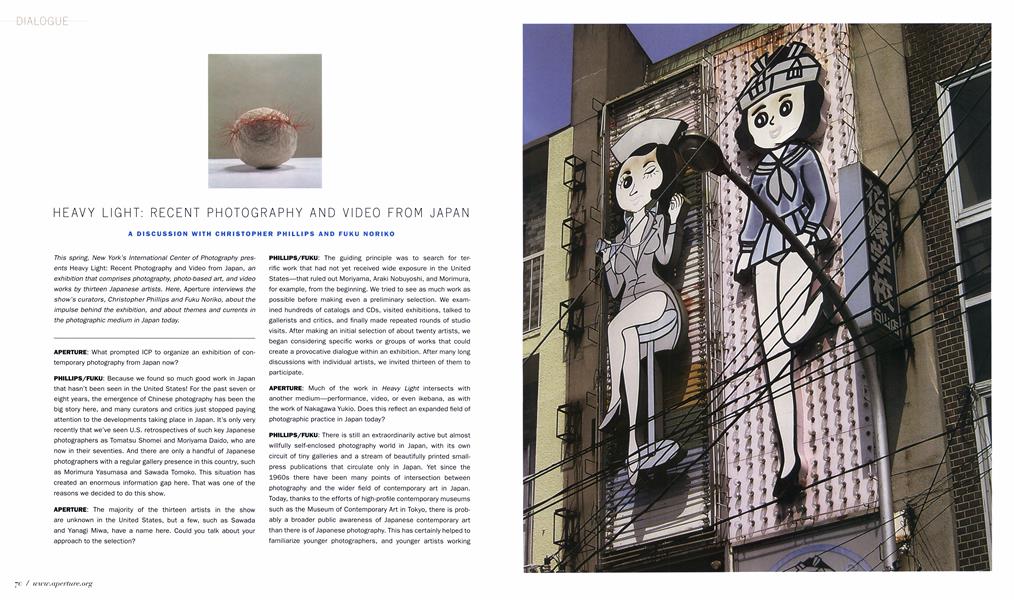

This spring, New York's International Center of Photography presents Heavy Light: Recent Photography and Video from Japan, an exhibition that comprises photography, photo-based art, and video works by thirteen Japanese artists. Here, Aperture interviews the show's curators, Christopher Phillips and Fuku Noriko, about the impulse behind the exhibition, and about themes and currents in the photographic medium in Japan today.

APERTURE: What prompted ICP to organize an exhibition of contemporary photography from Japan now?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: Because we found so much good work in Japan that hasn’t been seen in the United States! For the past seven or eight years, the emergence of Chinese photography has been the big story here, and many curators and critics just stopped paying attention to the developments taking place in Japan. It’s only very recently that we’ve seen U.S. retrospectives of such key Japanese photographers as Tomatsu Shomei and Moriyama Daido, who are now in their seventies. And there are only a handful of Japanese photographers with a regular gallery presence in this country, such as Morimura Yasumasa and Sawada Tomoko. This situation has created an enormous information gap here. That was one of the reasons we decided to do this show.

APERTURE: The majority of the thirteen artists in the show are unknown in the United States, but a few, such as Sawada and Yanagi Miwa, have a name here. Could you talk about your approach to the selection?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: The guiding principle was to search for terrific work that had not yet received wide exposure in the United States—that ruled out Moriyama, Araki Nobuyoshi, and Morimura, for example, from the beginning. We tried to see as much work as possible before making even a preliminary selection. We examined hundreds of catalogs and CDs, visited exhibitions, talked to gallerists and critics, and finally made repeated rounds of studio visits. After making an initial selection of about twenty artists, we began considering specific works or groups of works that could create a provocative dialogue within an exhibition. After many long discussions with individual artists, we invited thirteen of them to participate.

APERTURE: Much of the work in Heavy Light intersects with another medium—performance, video, or even ikebana, as with the work of Nakagawa Yukio. Does this reflect an expanded field of photographic practice in Japan today?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: There is still an extraordinarily active but almost willfully self-enclosed photography world in Japan, with its own circuit of tiny galleries and a stream of beautifully printed smallpress publications that circulate only in Japan. Yet since the 1960s there have been many points of intersection between photography and the wider field of contemporary art in Japan. Today, thanks to the efforts of high-profile contemporary museums such as the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, there is probably a broader public awareness of Japanese contemporary art than there is of Japanese photography. This has certainly helped to familiarize younger photographers, and younger artists working with photography, with the main directions in contemporary art around the world. You see the results in much of the recent photobased work being produced now in Japan.

APERTURE: There are many references to pop culture in the show. Is this part of a critique of culture or consumerism?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: It’s fascinating that in Japan, you don’t find the kind of marked division between fine art and commercial culture that has grown up in Europe or North America. For example, it’s still the case in Japan that major exhibitions are presented by department stores or shown in upscale shopping malls. Contemporary art, in particular, is part of the same cultural matrix as the worlds of fashion, animation, and manga, and shares many of the same attitudes about the value of distinctive visual style and the rapid turnover of ideas. Do the resulting works of art reflect a critique of popular culture or just an obsession with it? That’s hard to say.

APERTURE: The exhibition is divided into four thematic categories. Flow did you arrive at these?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: We’re assuming that most American audiences will have only a passing familiarity with recent Japanese art, photography, or culture. So we organized the exhibition into four broad sections that we hope will make it possible for viewers to grasp the unifying threads connecting works that may appear very different visually. One section consists of “post-landscape” work that

examines the relation between the natural world and the almost completely urbanized Japan of the present. A second section explores the survival and transformation of certain Japanese cultural traditions in the contemporary world. One especially lively section looks at the central role of costume and self-presentation in expressing Japanese identity today. And a final section considers the peculiar Japanese fascination with the figure of the child, evident in so much popular and artistic imagery.

APERTURE: In your selection there is a range of styles and approaches, for example, Ozawa Tsuyoshi is using photography as something of a conceptual tool, while Kajitani Naoki appears to reference street photography—a venerable tradition in Japan. Did you aim for a balance of artistic strategies, to represent a cross section of what photographers are up to in Japan today?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: Of course, with only thirteen artists in the exhibition, we tried to choose very distinctive works and to avoid overlaps of content or style. At the same time, we aren’t trying to present a sweeping, comprehensive picture of the full range of photographic activity in Japan today. There are still many devoted followers of such herofigures as Araki and Moriyama. And there is the continuing phenomenon of “girl photography,” especially in the publishing realm—books filled with sensitive, diaristic pictures made by young women photographers—that was launched with the success of Fliromix and Nagashima Yurie in the 1990s. In a grand overview of Japanese photography today, one would want to direct attention to those two areas— but actually, when we looked at these genres, we did not find work that we felt was really compelling enough to include in this show.

APERTURE: Nakagawa Yukio is known as a virtuoso practitioner of ikebana. Flow well known is he for his photography?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: Nakagawa, who’s in his eighties now, has long been recognized in Japan as the preeminent practitioner of avantgarde flower arranging. Because ikebana is an art of extreme transience—think of the lifespan of a flower—Nakagawa early on studied photography with Domon Ken as a way to record his extraordinary ikebana arrangements. These color studio photographs, made with a view camera, appeared in many of his publications, but it was only in the mid-1990s that he selected a group of his most memorable images and produced a portfolio. We think the photographs are remarkable in their own right, and we were determined from the outset that they would be part of the exhibition.

APERTURE: Over the past few years, ICP has mounted a number of large-scale exhibitions that focus on photography in specific countries or parts of the world, such as China, Africa, and now Japan. How important is place as an organizing principle in an increasingly globalized art world?

PHILLIPS/FUKU: Wherever you travel around the world today, you find a thin layer of the kind of globalized consumer culture that we all know: Starbucks, Armani, Blackberry, Louis Vuitton, iPod. But if you take a moment to scratch that thin surface layer, you always discover rich, complicated local cultures that are continuing to develop according to their own dynamics. That’s where the most interesting art and photography are coming from at present, and it’s certainly what we discovered in Japan. If we can convey something of this in Heavy Light at ICP, we’ll consider the show a success.©

Heavy Light: Recent Photography and Video from Japan will be presented at the International Center of Photography, New York City May 16-September 7, 2008.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Essay

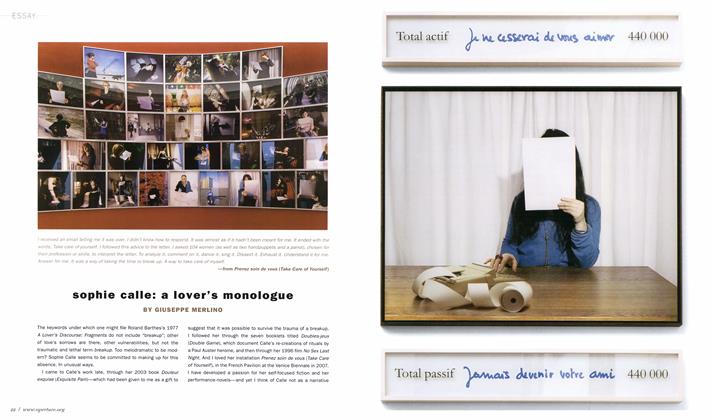

EssaySophie Calle: A Lover's Monologue

Summer 2008 By Giuseppe Merlino -

Work In Progress

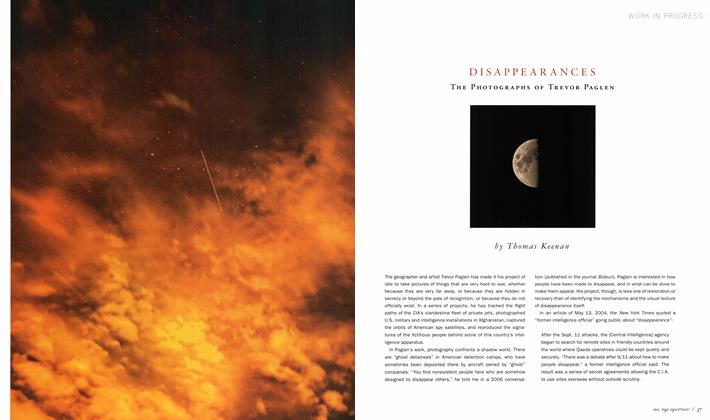

Work In ProgressDisappearances The Photographs Of Trevor Paglen

Summer 2008 By Thomas Keenan -

Witness

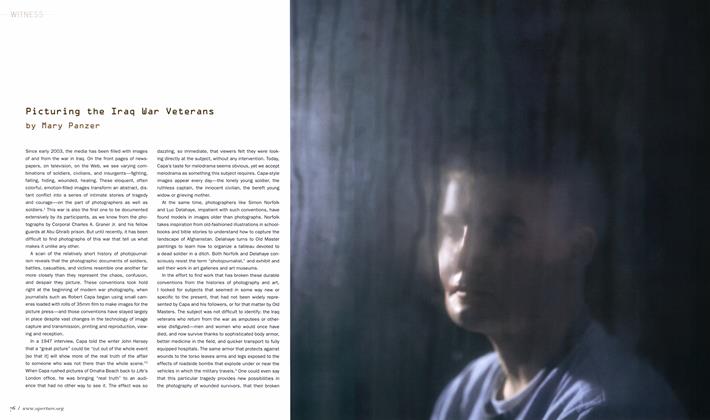

WitnessPicturing The Iraq War Veterans

Summer 2008 By Mary Panzer -

Film

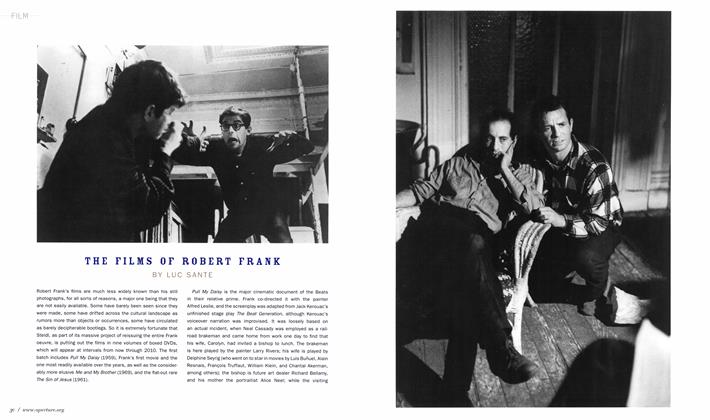

FilmThe Films Of Robert Frank

Summer 2008 By Luc Sante -

Mixing The Media

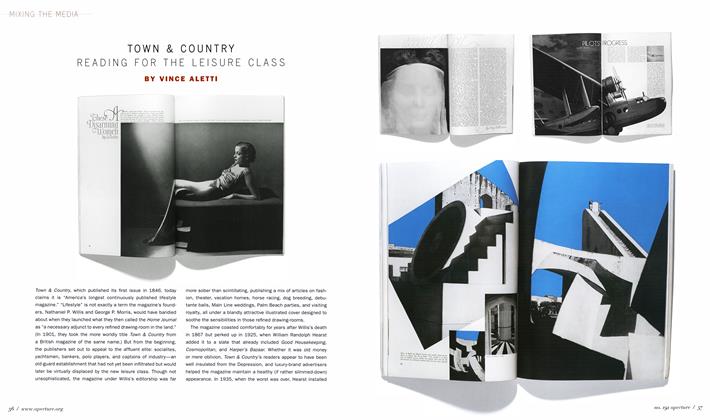

Mixing The MediaTown & Country Reading For The Leisure Class

Summer 2008 By Vince Aletti -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessJane Hammond's Recombinant Dna

Summer 2008 By Amei Wallach

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Dialogue

-

Dialogue

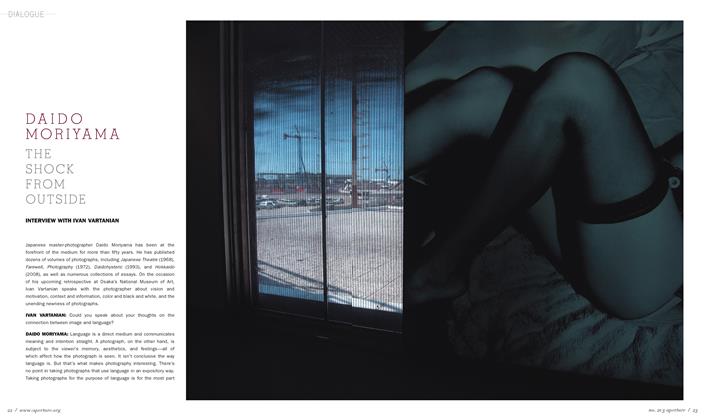

DialogueDaido Moriyama The Shock From Outside

Summer 2011 -

Dialogue

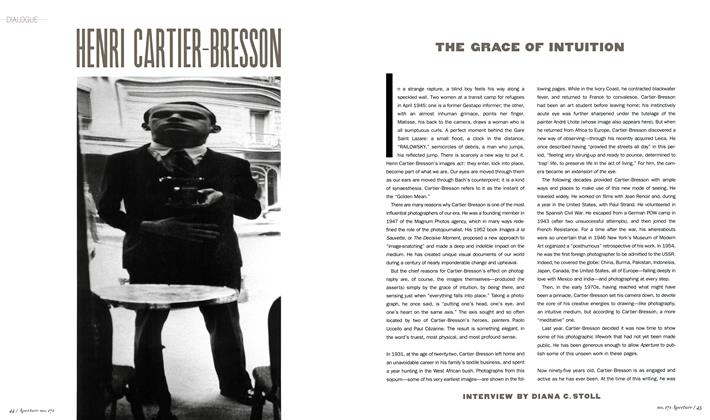

DialogueHenri Cartier-Bresson

Summer 2003 By Diana C. Stoll -

Dialogue

DialogueUnpacking My Library

Summer 2005 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Dialogue

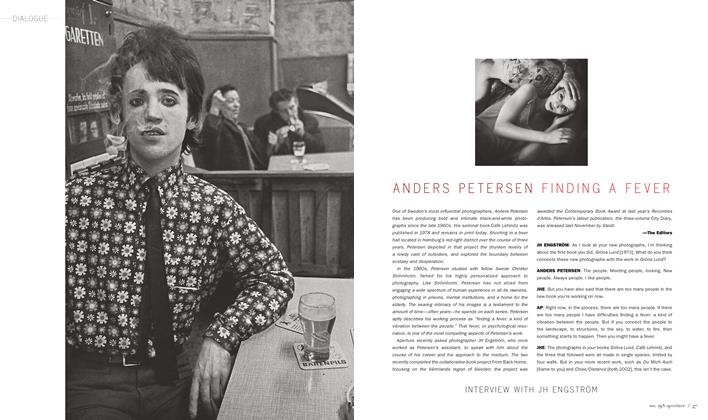

DialogueAnders Petersen Finding A Fever

Spring 2010 By The Editors, Jh Engström -

Dialogue

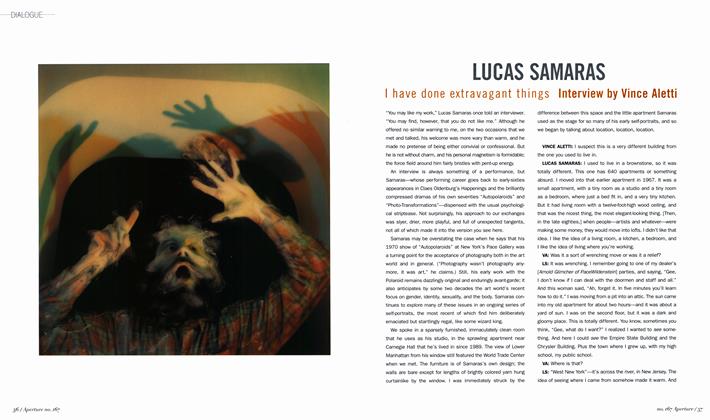

DialogueLucas Samaras

Summer 2002 By Vince Aletti -

Dialogue

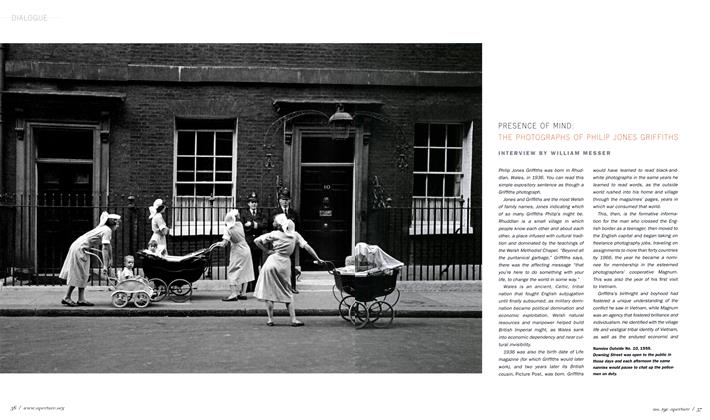

DialoguePresence Of Mind: The Photographs Of Philip Jones Griffiths

Spring 2008 By William Messer